Morphea is a form of localized scleroderma that differs from systemic forms of the disease by the presence of well-characterized morphological variants and the absence of any clinically detectable extracutaneous involvement. Many clinical classifications are employed, but there are few management guidelines for use in daily clinical practice.1 The most recently published guideline includes the following clinical variants: circumscribed morphea, generalized morphea, and the linear variant, which is more typical in childhood.2 The linear variant is subdivided into 3 subtypes: the purely linear form, coup de sabre morphea, and progressive facial hemiatrophy (or Parry-Romberg syndrome).

We present the case of a 7-year-old boy with no past medical or family history of interest. He was seen for a 7-mm long, depressed, hypopigmented, slightly indurated band located on the left upper lip (Fig. 1). The lesion had appeared more than 18 months earlier and had not previously been treated.

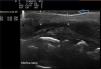

The possibility of performing a diagnostic biopsy was discussed with the family, but, given the cosmetic repercussion, it was decided to use skin ultrasound to confirm the clinical diagnostic suspicion. The ultrasound device employed was the Mylab™25 (Esaote) with a compact linear 18MHz probe. The study was used to support the clinical diagnosis and in particular to ensure correct monitoring of the disease. To perform an accurate study of dermal and epidermal thickness requires a thick layer of gel to obtain a high-quality image; pressure must not be applied to the skin, as this could distort the image. The ultrasound image revealed thinning of the epidermal layer and of the dermosubdermal space, with increased echogenicity of the dermis compared with the adjacent skin (Fig. 2). Doppler mode did not reveal increased vascularization in the area of the lesion. The neurological examination was rigorously normal, and additional laboratory tests were not requested. A diagnosis of inactive linear morphea was made on the basis of the clinical appearance and a compatible ultrasound image, and it was decided to take a wait-and-see approach.

Localized linear scleroderma is characterized by the presence of sclerotic bands with a linear distribution and hypo- or hyperpigmentation; the bands usually arise on the upper or lower limbs. These linear lesions may follow the Blaschko lines, signifying that genetic mosaicism may contribute to the pathophysiology of the disease.3 Large, deep lesions may be associated with muscle and bone atrophy and functional limitation due to joint involvement.

Ultrasound is a useful method for the diagnosis and, in particular, for the follow-up of diseases that affect the dermis and subcutaneous cellular tissue.4,5 Although the ultrasound findings are sometimes nonspecific, as occurred in our case, they can be very useful when combined with the patient's clinical manifestations to clarify the differential diagnosis. Most research into linear scleroderma reported in the literature describes the use of 20MHz probes, as they reach a maximum depth of 10mm, which should be sufficient to determine the thickness and echogenicity of the lesion.6

Evaluation of the clinical activity of localized scleroderma can be complicated, as it is based on observation of the clinical manifestations: presence or absence of erythema, lesion spread, or appearance of new lesions.

However, the progression of morphea can initially affect deeper layers and be clinically undetectable. This can delay the early initiation of treatment.7

The difference in thickness between affected skin and normal skin does not correlate with disease activity. The different characteristics that should be taken into consideration are overall echogenicity of the lesion, hypoechogenicity of the hypodermis, and increased vascularization of the deep dermis. These parameters, which do appear to correlate with increased clinical activity,8 were evaluated in our patient and enabled us to take a wait-and-see approach. When morphea is in a clinically stable phase, skin ultrasound reveals only a minimal difference in overall echogenicity between affected skin and normal skin, as was found in our patient.9,10

In conclusion, skin ultrasound is a non-invasive technique that can reduce the need for skin biopsy, particularly when the clinical findings are highly suggestive, as in our patient, or when histology has already been performed, avoiding cosmetic repercussions in visible areas. The dermatologist must learn to perform ultrasound studies, as they enable plaques of morphea to be monitored and contribute not only to the ability to take a wait-and-see approach but also to monitoring the efficacy of treatments.

Please cite this article as: Pérez-López I, Garrido-Colmenero C, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Tercedor-Sánchez J. Monitorización ecográfica de la morfea lineal de la infancia. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:340–342.