The patient was a 46-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis, for which she was in her third year of treatment with oral corticosteroids (deflazacort, 6 mg/d) and methotrexate (10 mg/wk). She was seen for ulcerative lesions in the right abdominal fold that had appeared 7 days earlier.

Physical ExaminationPhysical examination revealed an ulcer of 50×20mm with a fibrinous base, a violaceous border, and small adjacent ulcerations (Fig. 1). The lesion had been initially treated for 20 days with betamethasone-gentamicin (Diprogenta), which caused worsening of the larger lesion (Fig. 2).

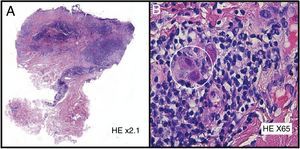

HistopathologyHistology of a skin biopsy revealed an absent epidermis, which had been replaced with granulation tissue, and the presence in endothelial cells of focally distributed, basophilic, intranuclear viral inclusions surrounded by a clear halo (Fig. 3). The diagnosis was confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of the tissue.

What Is Your Diagnosis?

DiagnosisSkin ulcers due to cytomegalovirus (CMV).

Clinical Course and TreatmentThe lesion evolved favorably and resolved spontaneously after 1 month. The patient was referred to the internal medicine and ophthalmology departments, where systemic and ophthalmological involvement, respectively, were ruled out. Serological tests revealed that the patient was positive for anti-CMV immunoglobulin (Ig) G.

The clinical picture was interpreted as likely reactivation of a CMV infection, with exclusively cutaneous involvement, in a patient with low-level immunosuppression secondary to treatment of the underlying disease.

CommentCMV, also known as human herpesvirus 5 (HHV-5), is a DNA virus belonging to the herpesvirus family. It is estimated that half of the general population comes into contact with this virus during their lifetime.

The virus is secreted in the bodily fluids of infected patients, and very close contact between individuals is required for transmission.1 After primary infection, which can be symptomatic or asymptomatic, patients generate anti-CMV antibodies that persist for life. The virus can remain latent, reactivating in response to immunosuppression, particularly cellular immunosuppression. Circulating antibodies against CMV are found in 30% to 50% of adults in Spain. This percentage is higher in developing countries, homosexual populations, and patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).1

In immunocompromised patients, CMV most often affects the respiratory, digestive, and central nervous systems; skin involvement is rare, and is usually an indicator of severe and generalized disease, with a mortality rate of over 80%.2–5

CMV infection predominantly affects the genitoperineal area,1,2,5,6 and has a highly variable clinical presentation (papules, nodules, verrucous plaques, vesicles, purpura, and ulcerations), which is secondary to the direct cytopathic effect of the virus on the endothelial cells of the dermis.4 Diagnosis is established mainly based on histology, which reveals giant cytomegalic endothelial cells with large, basophilic, intranuclear inclusions surrounded by a clear halo (owl's-eye cells).1,2,4 Immunostaining with anti-CMV monoclonal antibody can be very useful.2 Serology can help distinguish primary infection from reactivation, but is less useful in HIV-positive patients, in whom anti-CMV IgM antibodies are detected in both cases.1 While cell culture and immunohistochemical techniques are also useful, PCR is the gold standard diagnostic technique owing to its high sensitivity and specificity.1

Early treatment of affected patients with ganciclovir can reduce morbidity and mortality.1,3,4

In immunocompetent hosts, CMV infection can be oligosymptomatic (90%) or can give rise to a mononucleosis-like presentation characterized by fever, chills, hepatic alterations, and atypical lymphocytosis, in some cases accompanied by a rubelliform rash. Isolated skin involvement, which is even more rare, typically occurs in patients with primary CMV infection, and has a good prognosis.1

Please cite this article as: Martínez-González MI, Goula-Fernández S, González-Pérez R. Úlceras en abdomen. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:311–312.