The concept of reactive arthritis (ReA) defines a subgroup of peripheral spondyloarthritis that frequently occurs after an infectious process of the GI or genitourinary tract.1,2 It usually presents in young adults with a positive HLA-B27 genotype. Mucocutaneous signs can be observed in more than 50% of patients and include keratoderma blennorrhagicum, circinate balanitis, oral ulcers, ulcerative vulvitis, and psoriasiform nail changes.3 However, in rare cases, the disease is associated with the full spectrum of symptoms, which can pose diagnostic challenges.

From 2007 through 2022, we reviewed patients with ReA syndrome seen in a tertiary-level Dermatology service. The clinicopathological, analytical, and evolutionary characteristics of those who met the diagnostic criteria—established at the Fourth International Workshop on Reactive Arthritis in 1999—2 with cutaneous-mucosal signs were put on record. However, we also included those who had not been definitively diagnosed with ReA due to the absence of a clear episode of arthritis but had typical dermatological samples associated with a relevant infectious history. In this regard, our case series is representative of the significant clinical and temporal variability of this process and the diagnostic challenge it may present.

Regarding the mucosal expressions observed in our research, circinate balanitis (fig. 1, case #3) was observed in 5 patients (71.4%), while 3 of the 7 subjects (42.8%) exhibited recurrent oral ulcers. One of them had nail dystrophy associated with typical keratoderma blennorrhagicum (14.2%), whose histological study revealed psoriasiform epidermal hyperplasia, spongiform pustules, neutrophilic exocytosis, and a lymphohistiocytic perivascular inflammatory infiltrate in the superficial dermis. Case #3 presented with multiple psoriasiform plaques on the forearms associated with dactylitis (fig. 2). Dactylitis was present in 2 of the 7 patients along with joint symptoms. Three patients (42.8%) exhibited conjunctivitis during the course of the disease.

Diagnosis is fundamentally clinical, based on medical history and thorough physical examination.1–7 There is no consensus on the diagnostic criteria for ReA.2 Moreover, atypical or incomplete forms of the disease have been described on numerous occasions.3 In our series, the characteristic triad of urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis was reported in only 3 patients (42.8%), and joint symptoms did not always precede or accompany the mucocutaneous outbreak. Moreover, in more than 10% of cases, the infection can be subclinical and go completely unnoticed.5 Of note that, based on the characteristic dermatological signs, an initial diagnosis could be established or guided in 5 of the 7 medical cases, underscoring the need for dermatologists to become familiar with associated mucocutaneous presentations.

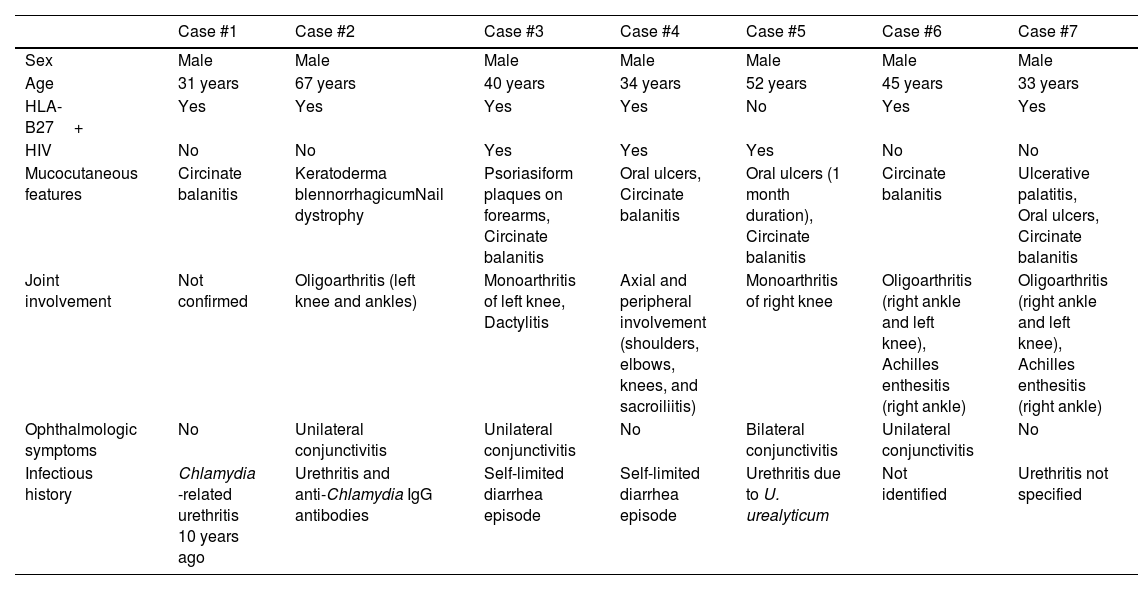

All our patients were men aged between 31 and 67 years. Urogenital infection-related ReA is more common in males, while ReA associated with GI problems affects both sexes equally.4 In our cases, we detected an absolute predominance in middle-aged men. Some authors attribute this high percentage to the elevated rate of asymptomatic infections in the female population,4 complicating the detection of the antecedent that would lead to diagnosis (Table 1).

Case reports. Clinical and evolutionary characteristics.

| Case #1 | Case #2 | Case #3 | Case #4 | Case #5 | Case #6 | Case #7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male | Male |

| Age | 31 years | 67 years | 40 years | 34 years | 52 years | 45 years | 33 years |

| HLA-B27+ | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| HIV | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Mucocutaneous features | Circinate balanitis | Keratoderma blennorrhagicumNail dystrophy | Psoriasiform plaques on forearms, Circinate balanitis | Oral ulcers, Circinate balanitis | Oral ulcers (1 month duration), Circinate balanitis | Circinate balanitis | Ulcerative palatitis, Oral ulcers, Circinate balanitis |

| Joint involvement | Not confirmed | Oligoarthritis (left knee and ankles) | Monoarthritis of left knee, Dactylitis | Axial and peripheral involvement (shoulders, elbows, knees, and sacroiliitis) | Monoarthritis of right knee | Oligoarthritis (right ankle and left knee), Achilles enthesitis (right ankle) | Oligoarthritis (right ankle and left knee), Achilles enthesitis (right ankle) |

| Ophthalmologic symptoms | No | Unilateral conjunctivitis | Unilateral conjunctivitis | No | Bilateral conjunctivitis | Unilateral conjunctivitis | No |

| Infectious history | Chlamydia -related urethritis 10 years ago | Urethritis and anti-Chlamydia IgG antibodies | Self-limited diarrhea episode | Self-limited diarrhea episode | Urethritis due to U. urealyticum | Not identified | Urethritis not specified |

U. urealyticum: Ureaplasma urealyticum; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

It is recommended to determine acute-phase reactants (polymerase chain reaction [PCR], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR]), HLA-B27 detection, and serological tests for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and try to identify the responsible causative agent (via cultures, PCR, or serologies) based on the clinical signs of each case. Depending on different geographical areas, age, and sex, multiple microbial agents have been implicated, and in our series, it is consistent with the literature that the germ most commonly associated was Chlamydia trachomatis.5,6 In more than 10% of cases, the predisposing infection can be subclinical and go unnoticed.3

A total of 85.71% of patients tested HLA-B27 positive, which amounts to 60% up to 85% of ReA cases, while the prevalence of this haplotype in the general population is 10%.1,2 Although HLA-B27 determination is not a diagnostic criterion, it can guide diagnosis and is associated with a higher number of extra-articular signs.7 In line with these findings, in our series, the patient with the least cutaneous symptoms was HLA-B27 negative. Additionally, these patients tend to have a more chronic course, a higher frequency of extra-articular signs, and a worse prognosis.5 Mucocutaneous expressions are more commonly seen in HLA-B27 positive individuals and usually occur 1 to 4 weeks after the infectious process,3 though there is great variability in their timeline, sometimes appearing months or even years after the triggering infectious episode9,10 as it occurred with case #1.

Furthermore, 57.1% of patients had associated HIV infection. This syndrome has been reported in up to 10% of people living with HIV, with studies showing that in HLA-B27 positive individuals, HIV triples the risk of developing the disease.10 Since this group tends to exhibit more aggressive and refractory ReA, most authors recommend testing for it.1,3,8

Regarding cases that could be categorized as atypical, one of our patients did not exhibit joint symptoms, which raises doubts on the diagnosis of ReA. The observation of isolated characteristic dermatological signs could be the consequence of either an isolated cutaneous process with possible shared pathogenic mechanisms with ReA or a true ReA with low/absent joint expressivity.

In conclusion, the disease exhibits great heterogeneity with highly variable clinical features in terms of number, presentation, and severity. Hence the importance of history-taking and thorough physical examination, especially dermatological,9,10 in cases with incomplete or atypical forms.

FundingNone declared.