Hypereosinophilic syndrome (HES) is defined by a concentration of eosinophils in peripheral blood greater than 1500cells/μL, accompanied by organ damage or dysfunction not attributable to other causes.1–4

HESs include the lymphoproliferative form (L-HES), in which there is an abnormal T-cell (TC) population in peripheral blood, with clonal rearrangement of the TC receptors (TCRs). These produce eosinophil-derived cytokines. Therefore, unlike the clonal myeloproliferative variant, L-HES is a mixture of a clonal process (TC clones) and a reactive one (eosinophilia derived from the secretion of cytokines from these TCs).1,2,4–6

Close follow-up of these patients is essential, as 10–20% may progress to cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) with a poor prognosis.7,8 It is important to distinguish between the 2 entities, given the indolent course in the case of patients with L-HES compared with the worse prognosis in CTCL.

A 67-year-old man attended the clinic with symptoms of 3 months standing of polyarthralgia, multiple migratory bilateral pulmonary infiltrates, generalized highly itchy maculopapular skin rash, and constitutional syndrome with asthenia, anorexia, and weight loss (Fig. 1).

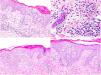

Laboratory analysis showed leukocytosis of 58600/μL with neutrophilia of 11100/μL and eosinophilia of 44100/μL, with elevated acute-phase reactants (CRP, 147.5mg/L; VSG, 46mm/h; LDH, 335U/L). Study of urine, allergies, echocardiogram, autoimmunity, serology, and parasites was negative. A mutation in the FIP1L1-PDGFRA gene was ruled out by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) in peripheral blood. Bone marrow study showed increased eosinophils with a high percentage of lymphocytes with atypical immunophenotype (CD3−, CD4−, and CD8−). The histological study of a punch biopsy showed spongiotic dermatitis with eosinophils and follicular involvement (Fig. 2).

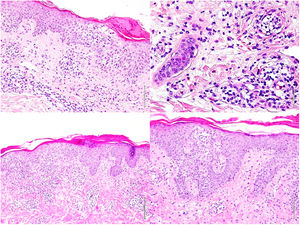

Skin biopsies. Upper images (1st biopsy): epidermis with marked spongiosis, exocytosis of inflammatory cellularity forming intraepidermal vesicles and foci of parakeratosis with a perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes and numerous eosinophils. Lower images (2nd biopsy): epidermis with moderate acanthosis and focal parakeratosis. A lymphoid infiltrate with marked epidermotropism can be observed in the papillary dermis, along with formation of a Pautrier microabscess.

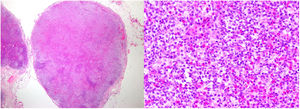

With these results, L-HES was suspected and prednisone 60mg/24h, hydroxyurea 500mg/24h, and methotrexate 20mg/week were administered. One month later, the patient presented with a notable worsening of symptoms, with the onset of large swollen lymph nodes on the right side of the groin. Another skin biopsy (Fig. 2) showed a T lymphoid infiltrate with epidermotropism and abundant eosinophils and a lymph node biopsy revealed complete loss of architecture (Fig. 3). These cells were positive for CD3, CD4, and CD5, with loss of CD7, and negative for CD8, CD20, and CD30, presenting monoclonality for TCR beta and gamma. Likewise, the presence of Sézary cells in peripheral blood was ruled out, as well as systemic involvement. These findings led to diagnosis of erythrodermic mycosis fungoides with lymph node involvement (stage IVA2). In accordance with this diagnosis, prednisone 45mg/24h, interferon alfa 2a 3 MIU (3 injections per week), bexarotene 300mg/24h, and weekly methotrexate 20mg were administered. In light of the poor therapeutic response, and with the suspicion of underlying Sézary syndrome, the lymphoid phenotype was reassessed and the presence of Sézary cells was detected, with 2.2% atypical TCs and a CD4/CD8 ratio of 9.09, with 5% positive for CD3, CD2, CD5, and negative for CD7, CD4, CD8, and CD26, and eosinophilia of 62% in the flow cytometry. The final diagnosis was Sézary syndrome (stage IVA2). Chemotherapy was started with the CHOP regimen. The patient died 4 days after starting treatment.

The case analysis questions whether the patient had CTCL from the start and whether the hypereosinophilia was reactive to this entity or whether it was malign progression from L-HES. Transcriptome analysis has determined specific biomarkers for each entity in some studies, thereby enabling these 2 entities to be identified early.6,9 Our impression is that the patient probably had Sézary syndrome from the outset and that hypereosinophilia was reactive and manifest as L-HES.

Eosinophilia has an important prognostic role in CTCL, with median survival 3 years lower in patients with eosinophil levels above 700/μL. Some authors have considered eosinophilia on diagnosis as the only prognostic variable associated with disease progression and disease-related death.10 In addition, eosinophils could be an indirect marker of tumor load, as their level increases due to synthesis of eosinophil-derived cytokines by neoplastic cells and they therefore may be useful as response markers for antitumor treatment. Further studies to confirm this hypothesis could help guide treatment in these patients.5,10

In summary, we can conclude that it is extremely difficult to know whether we are facing natural disease progression or an undiagnosed lymphoma, highlighting the need for more reliable markers to address this question. What we can say, based on the literature, is that eosinophilia is a warning sign for patients with CTCL, and long-term follow-up patients with L-HES are vital.