A physician's aim is to preserve health and cure illness, as we have seen during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

In 1880, it was sexually transmitted infections (STIs) that wreaked havoc in communities, and available treatments were ineffective. Mercury was the only recourse, and it was not always well tolerated.

Dr Juan de Azúa y Suárez (Madrid, 1858–1922), a dermatologist and the first full professor of dermatology and syphilology on the medical faculty of the University of Madrid,1 approached his work from the standpoint of public health, or hygiene, in an effort to control STI transmission. He described himself as an “interventionist in this and all questions of health.”2

Endowed with an extraordinary gift of observation as well as acumen, Azúa approached the Royal Health Council in 1904 with a proposal to regulate public hygiene with regard to prostitution (Reglamento de la Sección de Higiene de la Prostitución).2 His plan centered around 11 points through which he argued in favor of innovations such as the creation of a health police force and the employment of public health physicians. In an epilog to the proposal, he laid out what he called his “health advisories” (avisos sanitarios) in 2 appendices.

Azúa had previously presented the advisories at an international medical conference in Rome in 1894. They described the prophylactic treatments being used for various skin infections and STIs in patients at Hospital de San Juan de Dios in Madrid.2,3

The importance of Azúa's approach lay in his effective outreach to the general public to convey information about health and hygiene on a topic toward which attitudes had progressed little and which would have been considered a “moral” issue at the time.

The advisories were meant to be printed. They gave information about syphilis and the blennorrhagias, or mucous discharges, of gonorrhea and other infectious diseases such as leprosy and forms of ringworm. Details referred to the mechanisms of contagion and precautions to take to avoid catching these diseases.

Azúa wrote the material himself and covered the cost of printing it, demonstrating conscientiousness and dedication to the fight against STIs.

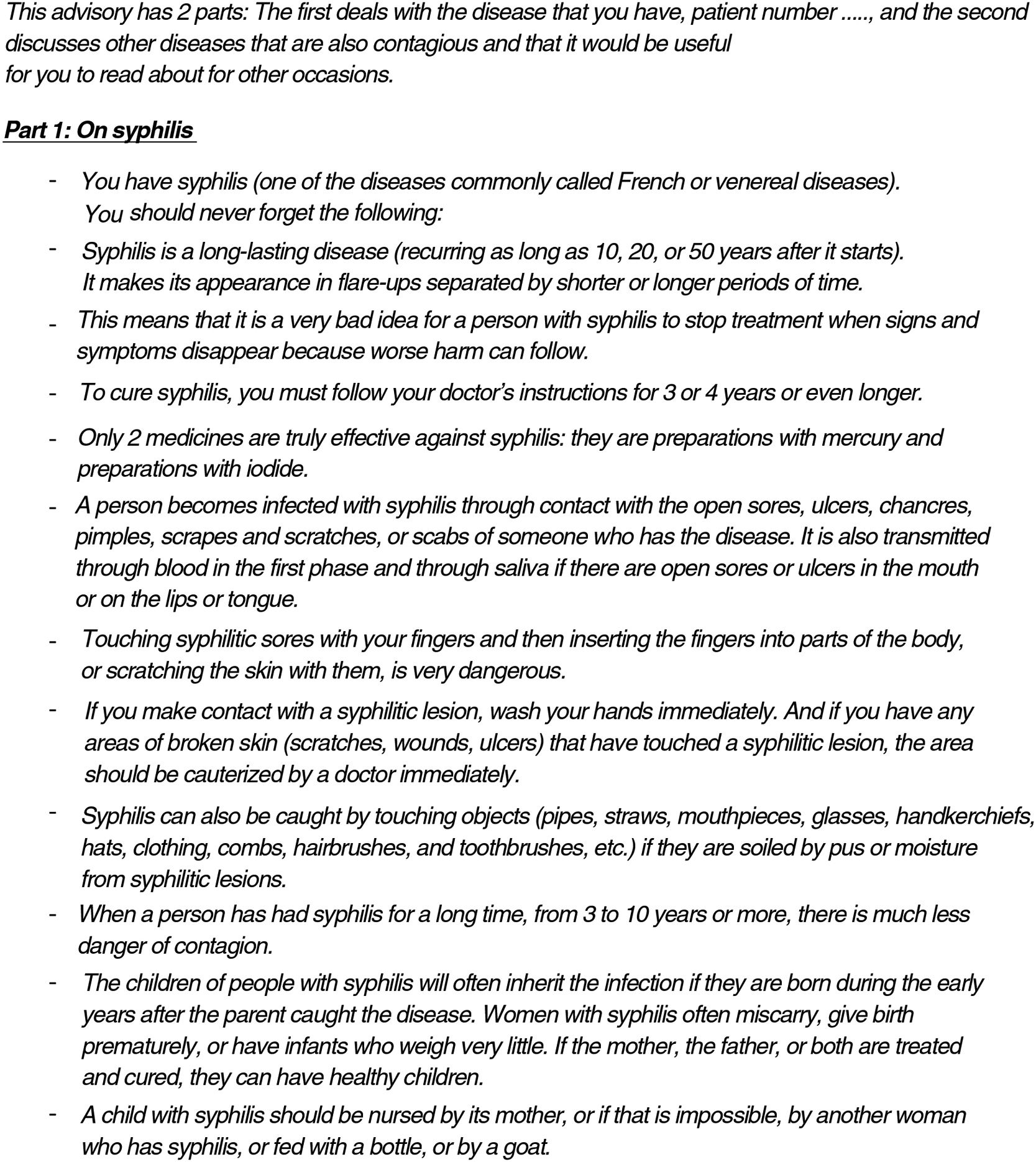

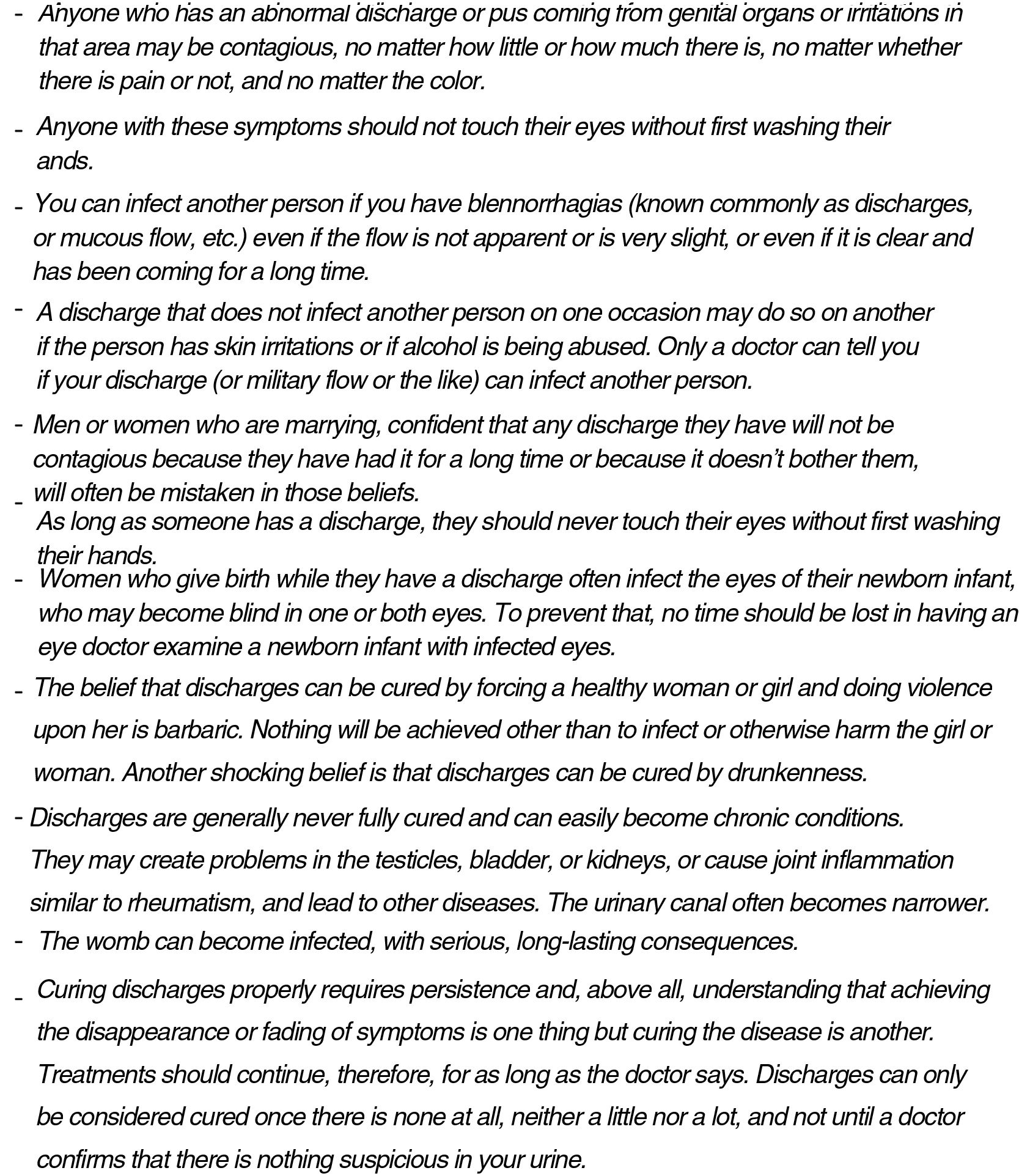

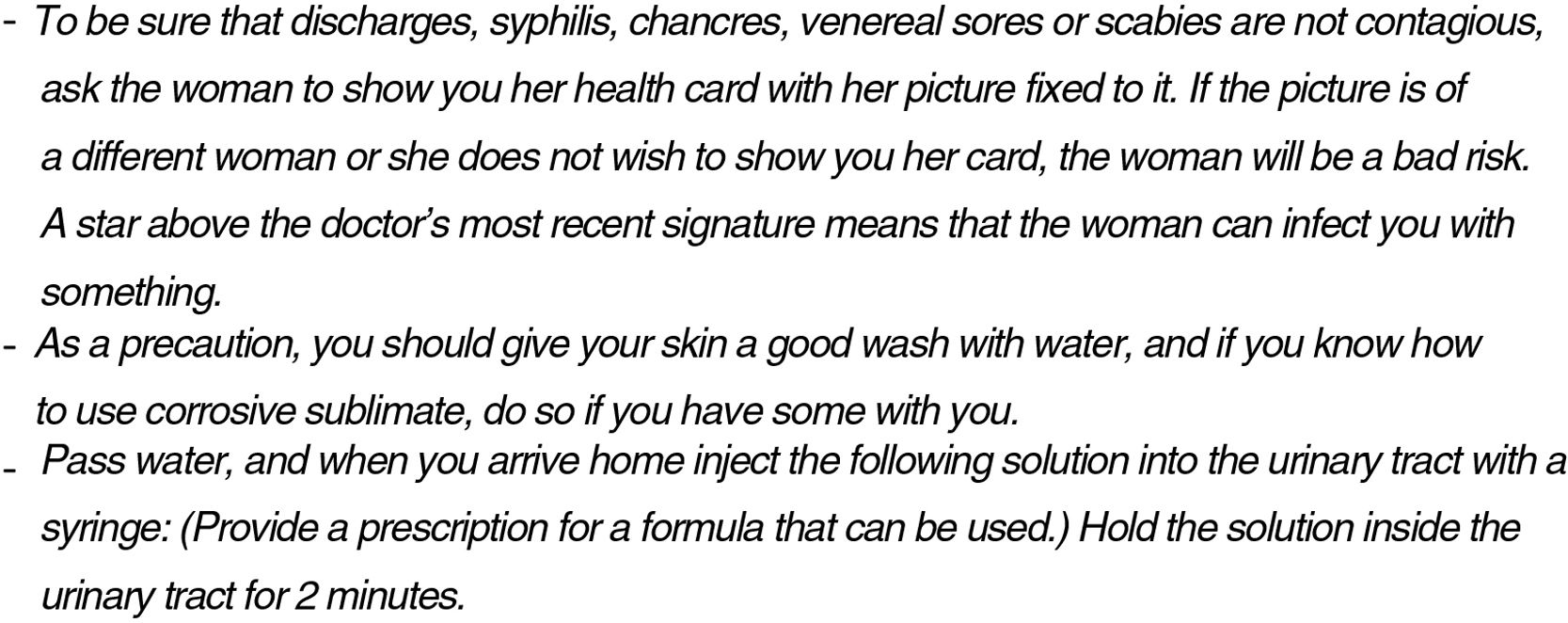

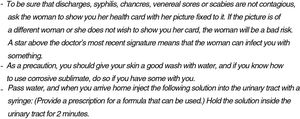

The advisories in the 2 appendices are shown in Figs. 1–3. Appendix I, with 2 parts (Figs. 1 and 2), contained texts addressing patients at his hospital's clinic. The first part covered the prevention of syphilis and the second treated the topic of mucous discharges in gonorrhea and other diseases. Appendix II (Fig. 3) addressed the clients of so-called houses of tolerance or anyone coming into contact with prostitutes.

The first part of Appendix I to Dr Azúa's public health proposals, in which he gives advice on syphilis. (Translator's note: The translated instructions are of transcriptions of the versions in Del Río de la Torre's thesis on the origins of the Madrid school of dermatology.3).

The advisories in the second part of Appendix I to Dr Azúa's public health proposals. This section covered the management of mucous discharges (blennorrhagias). (Translator's note: The translated instructions are of transcriptions of the versions in Del Río de la Torre's thesis on the origins of the Madrid school of dermatology.3).

The advisories in Appendix II to Dr Azúa's public health proposals. This appendix contained information related to contact with prostitutes working in so-called houses of tolerance. (Translator's note: The translated instructions are of transcriptions of the versions in Del Río de la Torre's thesis on the origins of the Madrid school of dermatology.3 “Corrosive sublimate” is an archaic name for mercuric chloride, HgCl2.).

The advice is written in plain language for the layperson (para elvulgo3) and includes examples as well as explicit instructions delivered unceremoniously.3 The information was intended to be intelligible, practical, and instructive. By way of example, consider the following excerpt:

“These advisories serve

- -

“To make clear to readers the harms that contagious (or catching) diseases cause.

- -

“To help readers keep from catching contagious diseases most of the time, by means of understanding when and how they are transmitted.”3

The advisory information had also been presented at the Ninth International Conference of Public Health and Demography (Congreso Internacional de Higiene y Demografía) held in Madrid in 1898.3

Azúa's provision of these health advisories represents a historical milestone in Spanish dermatology. By designing informative leaflets focused on preventing STIs, he displayed great insight into and commitment to the health of individuals and the community. To his disappointment, however, they failed to carry weight in society because of the widespread illiteracy of his day. Nonetheless, his efforts were not entirely in vain. In 1910 a royal decree was issued to create a department to regulate hygiene in prostitution (Servicio de Higiene de la Prostitución) under the jurisdiction of the provincial health services. Yet another royal decree 8 years later empowered the Ministry of the Interior (Gobernación) to establish regulations aimed at preventing syphilis and other STIs in Spain. In 1925, municipal health regulation 63 obliged the creation of outpatient clinics dedicated to these infections. In 1928, the act of infecting others was criminalized in article 538 of the penal code.2 Among the dermatologists who followed in Azúa's footsteps, maintaining his approach to public health education and the care of patients with STIs, were Gaspar Bravo de Sobremonte, José Sánchez-Covisa, and Álvarez Sainz de Aja.3,4

Sainz de Aja published 4 of his own health advisories in the journal Ecos Españoles de Dermatología y Sifiliografía in 1929. They addressed the needs of patients with syphilis, mucous discharges, venereal chancers, and scabies.2,3

Over time, the old advisory pamphlets would be replaced by new means of communication, such as conferences, posters, and films. However, progress has not erased the evident value of these early efforts to raise public awareness.3,4

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.