When the dermoscopy of squamous cell carcinoma and its precursors we differentiate among keratin-related, vascular, and pigment-related criteria. Non-pigmented actinic keratoses are characterized by the “strawberry pattern”. Pigmented actinic keratosis shows a significant dermatoscopic overlap with lentigo maligna, but the presence of pigmented scales, erythema, and prominent follicles favors its diagnosis. Bowen's disease is characterized by clustered glomerular vessels, white-yellowish scales, and brown or grey dots arranged in lines in its pigmented variant. Finally, dermoscopy allows us to detect invasive squamous cell carcinoma in its early stages and differentiate it from its precursors. Furthermore, its presentation may vary depending on the degree of differentiation, with keratin-associated criteria predominating in well-differentiated tumors, while an atypical vascular pattern will predominate in poorly differentiated tumors.

En la evaluación dermatoscópica del carcinoma epidermoide y sus precursores diferenciaremos entre criterios relacionados con la queratina, criterios vasculares y criterios relacionados con el pigmento. Las queratosis actínicas no pigmentadas se caracterizan por el denominado “patrón en fresa”. Las queratosis actínicas pigmentadas presentan un gran solapamiento con el léntigo maligno, pero la presencia de escamas pigmentadas, el eritema y los folículos prominentes favorecen su diagnóstico. La enfermedad de Bowen se caracteriza por la presencia de agregados de vasos glomerulares y escamas blanco-amarillentas, así como por puntos marrones o grises dispuestos en líneas en su variante pigmentada. Por último, la dermatoscopia puede permitirnos la detección del carcinoma epidermoide invasivo en sus fases incipientes y diferenciarlo de sus precursores. Además, este variará en su presentación en función del grado de diferenciación, predominando los criterios asociados a la queratina en tumores bien diferenciados, mientras que en tumores mal diferenciados predominará un patrón vascular atípico.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most frequent skin cancer, representing approximately 20% of all non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC). The incidence of SCC is on the rise.1,2 The overall incidence rate in our region has been estimated at 38.16/100,000 persons/year.3 Although most SCCs evolve satisfactorily after surgical excision, there is a subgroup of high-risk lesions with a high probability of recurrence, metastasis, and disease-related death.1,3 Considering the progressive aging of the population and the corresponding increase in the incidence of NMSC—especially keratinocyte carcinomas—strategies aimed at the early diagnosis of malignant lesions and their differentiation from precursors are becoming increasingly important.

Dermoscopy is a non-invasive technique that is now an essential part of clinical diagnosis in dermatology. In experienced hands, it has been shown to improve diagnostic accuracy in both pigmented and non-pigmented skin lesions. Specifically, dermoscopy increases sensitivity in the diagnosis of SCC,4 with various patterns associated with different types of lesions and stages of progression having been described, which facilitates differentiating among actinic keratosis (AK), Bowen's disease (BD), and invasive SCC (iSCC)5,6 (Fig. 1). Similarly, pigmented AK (pAK) can pose diagnostic challenges due to its clinical overlap with lentigo maligna (LM), a scenario in which dermoscopy has also demonstrated its validity.5 This review aims to synthesize the existing literature with a practical approach, addressing the spectrum of keratinocytic neoplasms and their precursors from a dermoscopic perspective while unifying the considerable terminological heterogeneity existing in Spanish7 (Table 1).

Glossary of the main dermoscopic terms described in the literature in the spectrum of actinic keratosis, Bowen's disease, and invasive squamous cell carcinoma, along with their definition, schematic representation, and histopathological correlation.

| Criterion | Definition | Histopathological correlation | Schematic representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keratin-related criteria | |||

| Superficial white-yellow or brown scales | Structureless white-yellow or brown opaque areas | Areas of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis | |

| White clods (“keratin pearls”) | Rounded white-yellowish structures surrounded by a whitish halo | Keratin pearls or horn swirls | |

| White circles | Concentric white structures surrounding a follicular orifice, which may have a central yellow globular area | Acanthosis and hypergranulosis of the infundibular epidermis with a central keratin plug | |

| White structureless areas | Homogeneous areas that may cover a large part of the tumor, possibly associated with other white structures (circles, clods) | Hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis over a dysplastic epidermis or keratin in neoplastic cell aggregates | |

| “Rosettes” | 4 bright white dots arranged like a “4-leaf clover” | Optical effect of cross-polarization, resulting from alternating hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis in follicular orifices and/or concentric fibrosis | |

| Vascular criteria | |||

| Red pseudonetwork | Structureless erythematous areas and wavy vessels surrounding follicular orifices | Localized increase in vascularization along with variable follicular hyperkeratosis and keratinocyte atypia | See Fig. 1 |

| “Strawberry pattern” | Reddish pseudo-reticulum interrupted by prominent follicular orifices | See Fig. 1 | |

| Dotted vessels | Small caliber red dots resembling pinheads, densely packed together | Tips of short capillary loops in the papillary dermis | |

| Glomerular vessels | Larger caliber vessels than the dotted ones, convoluted or “coiled” resembling the renal glomerulus, often distributed in aggregates | Clustered and dilated capillaries in papillary dermis | |

| “Hairpin” vessels | Loop-shaped vessels in an oblique arrangement to skin surface, usually surrounded by a whitish halo in keratinizing tumors | Capillary loops in the papillary dermis in thick tumors | |

| Linear irregular | Linearly or slightly curved vessels of irregular shape, size, and/or distribution | Tumoral neoangiogenesis | |

| Polymorphous vascular pattern | Vessels of various morphologies, often including “hairpin,” irregular linear, and dotted/glomerular vessels in invasive squamous cell carcinoma | Tumoral neoangiogenesis | |

| Pigment-associated criteria | |||

| Brown follicular dots and circles | Small brown rings inside follicular openings | Presence of melanin in basal follicular cells at infundibular level | |

| Gray follicular dots and circles | Small gray rings inside follicular openings | Presence of melanin at isthmic level along with melanophages in the adjacent dermis | |

| Rhomboidal structures | Confluent gray dots in linear arrangement of gray-to-brown color between follicular openings | Pigmented keratinocytes in the Malpighian layer and/or melanophages in the superficial dermis | |

| Inner gray halo | Subtle homogeneous gray or beige halo around follicular openings, forming an inner ring in relation to the pigmented pseudo-reticulum network | Area of preserved epidermis around follicular openings, with gray color as a resulta of the “Tyndall effect” of pigmented keratinocytes beneath this normal epidermis | |

| Brown structureless pigmentation | Homogeneous brown areas without other dermoscopic structures | Diffusely distributed melanin in basal keratinocytes | |

| Patchy or brown/gray dots/globules arranged in lines | Brown or gray dots arranged in a patchy or linear way, often found at the lesion periphery with radial orientation | Melanophages in dermal papillae near papillary vessels along with thin suprapapillary epidermis and/or increased number of pigmented keratinocytes | |

| Other criteria | |||

| “Red starburst” | Presence of radial red lines or “hairpin” vessels around the central structureless white-yellow area of the lesion | May represent a sign of “horizontal” lesion growth | |

| Erosions | Small irregularly arranged structureless orange-to-red or brown areas | Loss of epidermis | |

| Ulceration | Large irregular or rounded structureless red or reddish-brown areas | Loss of epidermis and superficial dermis | |

This review will exclude SCC of the nail apparatus, which, due to its peculiarities and specific dermoscopic criteria, should be addressed in a separate work.

Dermoscopy of actinic keratosisNon-pigmented actinic keratosisKey aspectsNon-pigmented AK is frequently characterized by the so-called “strawberry pattern,” featuring a red pseudonetwork interrupted by prominent follicles. These can appear as “rosettes” under polarized light dermoscopy (Fig. 2).

Non-pigmented actinic keratoses. A) Grade 1 actinic keratosis on the face of an 81-year-old woman. Dermoscopy shows a red pseudonetwork and discrete scaling. B) Grade 2 facial actinic keratosis in a 72-year-old man. “Strawberry pattern,” with prominent follicles/“rosettes,” perifollicular wavy vessels, and keratin. C) Grade 3 actinic keratosis on the face of an 80-year-old woman. Dermoscopy shows keratin masses as white-yellowish structureless areas. D) Bowenoid actinic keratosis on the leg of an 80-year-old woman. Dermoscopy shows multiple dotted/glomerular vessels.

In an initial trial, Zalaudek et al. studied a total of 41 non-pigmented facial AKs and identified a total of 4 fundamental dermocopic structures: a red pseudonetwork (95%), superficial scales (85%), fine linear or wavy perifollicular vessels (81%), and prominent follicles (66%), and/or surrounded by a white halo (“targetoid”) (100%). The combination of these structures forms the metaphorically termed “strawberry pattern”.8,9 This pattern was later observed by the same group in 67% of lesions in their series, and is significantly associated with the diagnosis of AK vs BD/SCC/keratoacanthoma (KA) (p<0.001).10

Cuellar et al. described structures called “rosettes” (4 bright white dots resembling a “four-leaf clover”) in AK, only visible with polarized light11 (Fig. 2). However, these structures have subsequently been described in a wide range of neoplasms and even in non-lesional photo-damaged skin, which is why they are not considered specific.12 Lozano-Masdemont et al. later proposed that the “rosette pattern,” present in 35.8% of lesions in their series characterized by this structure as the predominant feature could, indeed, could be specific.13

From a practical standpoint and according to Olsen's clinical classification, we will be observing these structures with relative frequency, which will eventually allow us to classify AKs into 3 clinical/dermoscopic stages5 (Fig. 2):

Grade 1 AK: palpable, scarcely visible lesions characterized by a red pseudonetwork and discrete scaling under dermoscopy.

Grade 2 AK: visible, easily palpable, moderately keratotic lesions characterized by a reddish background with prominent follicles or “rosettes” under dermoscopy. This stage corresponds to the previously described “strawberry pattern”5.

Grade 3 AK: thick lesions with marked hyperkeratosis and well-demarcated borders, predominantly showing compact keratin masses as white/yellowish structureless areas under dermoscopy5,14.

Regarding locations, we should mention that non-pigmented extrafacial AKs may present certain dermoscopic differences. In their study, Reinehr et al. saw that whitish scales (97.3%) and erythema (57.4%) were the most common structures. The anatomical differences described in extrafacial skin (primarily the lower density of adnexal structures) imply that follicle-associated structures, and the red pseudonetwork are less common findings.15

The validity of dermoscopy for diagnosing AKs was confirmed by Huerta-Brogueras et al. in a prospective trial of 178 clinically suggestive AK lesions, with sensitivity and specificity rates of 98.7% and 95%, respectively, and a concordance of κ=0.917 between this technique and histopathology.16 Furthermore, dermoscopy also seems to be useful for post-therapeutic follow-up with cryotherapy, topical therapies, or photodynamic therapy (PDT).17,18

Pigmented actinic keratosisKey aspectspAK and LM present significant dermoscopic overlapping, primarily based on pigment-related criteria such as gray dots, rhomboidal structures, or asymmetric perifollicular pigmentation.

Additional findings, such as prominent follicles/“rosettes,” the presence of scales, erythema, or an inner gray halo at follicular level favor the diagnosis of pAK (Fig. 3).

Pigmented actinic keratoses. A) Pigmented actinic keratosis on the nose of a 70-year-old woman. Dermoscopy shows an annular/granular pattern, erythema, and prominent follicles. B) Pigmented actinic keratosis on the helix of an 85-year-old man. Dermoscopy shows a structureless brown area, erythema, and multiple “rosettes.” C) Pigmented actinic keratosis on the temple of a 56-year-old man. Dermoscopy shows pigmented scales and prominent follicles/“rosettes.”.

Diagnosing pAK can be challenging due to its clinical and dermoscopic similarity with LM19–22. In this regard, Akay et al. studied a total of 99 pigmented facial lesions (67 of them pAKs) and observed that the latter could exhibit dermoscopic criteria, such as gray dots (70%), an annular/granular pattern (39%), rhomboidal structures (36%), or asymmetric perifollicular pigmentation (25%).23 The study by Moscarella et al. with 17 facial and extrafacial pAKs revealed that the most common structures were gray dots (76.5%), structureless brown areas (58.8%), pigmented pseudonetwork (35.3%), and the presence of white circles in 11.7% of the cases. Same as LM, these authors observed an annular/granular pattern and asymmetric perifollicular pigmentation in 23.5% and 11.7% of cases, respectively20, while Kelati et al. found an annular/granular pattern and rhomboidal structures in 19.4% and 82.8% of 232 pAKs.22 However, certain dermoscopic criteria can aid in this difficult differential diagnosis. Lallas et al. studied a total of 70 LMs and 56 pAKs to find that the presence of white circles/prominent follicles (OR, 13.5; p=0.006), scales (OR, 7.7; p=0.001), and erythema (OR, 3.6; p=0.009) correlated with the diagnosis of pAK. Conversely, rhomboidal structures, intense pigmentation, and non-prominent follicles were predictors of LM.24 A recent study including 53 pAKs confirmed that erythema (35.8%), scales (77.4%), and prominent follicles (52.8%) could be key in identifying these lesions while also seeing structures shared with LM such as brown dots (22.6%) and circles (43.4%), gray dots (45.4%) and circles (26.4%), and structureless pigmented areas (30.2%).25 Finally, the presence of an “inner gray halo” at follicular level was reported by Nascimento et al. as a predictor of pAK vs LM, reporting this dermoscopic sign in 91.4% of pAKs vs 23.8% of LMs (p<0.01), with excellent inter-observer agreement (κ=0.846).26

Other variantsBowenoid AKs exhibit glomerular vessels of regular distributtion27,28 (Fig. 2), while lichenoid AKs can exhibit a gray annular/granular pattern due to melanophagia.5 Recently, the “iceberg sign” was described in AKs with a bluish surface coloration. The presence of this sign has been associated with the use of certain violet shampoos and the following deposition of amorphous basophilic material in the stratum corneum.29

Dermoscopy of in situ squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen's disease)Non-pigmented Bowen's diseaseKey aspectsNon-pigmented BD is characterized by the presence of clusters of glomerular or dotted vessels along with white/yellowish scales (Fig. 4).

Bowen's disease. A) Non-pigmented Bowen's disease on the temple of a 79-year-old woman. Dermoscopic pattern consists of white-yellowish scales and clustered glomerular vessels. B) Non-pigmented Bowen's disease on the back of a 55-year-old man. Dermoscopy shows discrete scaling and glomerular and dotted vessels. C) Pigmented Bowen's disease on the back of a 31-year-old man. Dermoscopy shows structureless brown pigmentation, clustered glomerular vessels, and brown and gray dots arranged in lines. D) Genital Bowen's disease on the pubis of a 59-year-old man. Dermoscopy shows a structureless brown pigmentation area, brown dots arranged in lines, dotted vessels, and shiny white lines.

In the initial study by Zalaudek et al. that analyzed 21 cases of BD found that the most common dermoscopic structures were glomerular vessels (90%) and white/yellowish scales (90%).30 These data were corroborated by the same group, observing these criteria in 43.3% and 83.1% of all 71 cases of BD, with significant differences vs AK. The authors also described the presence of a “red starburst” pattern in 28.2% of BD cases. Based on the AK-BD-SCC progression model, they hypothesized that this criterion could represent an initial step in such progression.10 In this regard, Pan et al. conducted a retrospective observational study with 50 cases of BD, 150 basal cell carcinomas (BCC), and 100 cases of psoriasis, concluding that the combination of clustered glomerular vessels and hyperkeratosis achieved a diagnostic likelihood of 98% for BD.31 Of note that vessel morphology may be influenced by the magnification used. Thus, with standard handheld dermatoscopes, we can see clusters of dotted vessels.32 In a recent study, Papageorgiou et al. observed that dotted and glomerular vessels were the main predictors of BD vs BCC. However, they also noted that dotted or glomerular vessels can be detected in BCCs located on the lower limbs, likely due to venous stasis (25% and 19.3% in the study, respectively).33 Aside from these fundamental findings, other described dermoscopic criteria include hemorrhages, focal hypopigmentation, linear irregular vessels, or “hairpin” vessels, among others.34–36 Additionally, dermoscopy seems useful at post-therapeutic follow-up with imiquimod. In a small patient series, Mun et al. saw reported that persistent glomerular vessels after treatment would be suggestive of the presence of residual tumor.34

Pigmented Bowen's diseaseKey aspectsPigmented BD is characterized by the criteria present in the non-pigmented form and the presence of structureless brown pigmentation and brown or gray dots arranged in lines (Fig. 4).

In an initial study by Zalaudek's group that analyzed 10 pigmented BD cases and reported brown globules with a patchy distribution (90%), as well as structureless gray or brown areas (80%).30 Afterwards, Cameron et al. published a retrospective study with 52 pigmented BD cases reporting the presence of brown or gray dots with a linear distribution pattern in 21.2% of cases. In 48.1% of cases, however, a structureless pigmentation pattern predominated, while 34.6% exhibited a combination of structureless pigmentation and dots. Most cases exhibited a monomorphic vascular pattern (82.9%), with predominance of glomerular vessels (44.2%), with a linear vessel distribution in 11.5%.37 Other studies have corroborated these findings in varying percentages, mainly the presence of glomerular vessels (50% up to 100%), pigmented dots/globules (30% up to 80%), or pigmented structureless areas (70% up to 78%).34,36,38

While these findings have proven reproducible in the genital area38 (Fig. 4), a study that analyzed a total of 79 head and neck lesions concluded that dermoscopic patterns in this location differ from previously published data and are similar to pAKs based on a lower presence of glomerular vessels (7.6%) and dots with linear arrangement (13.9%), the observation of structures, such as pigmented circles (48.1%) and white circles (17.7%), rhomboidal structures (41.8%), and structureless pigmentation areas (86.1%), as well as the predominance of linear irregular (29.2%)39 (Fig. 5). Other less consistently described dermoscopic criteria include projections, pigment network, hypopigmented areas, or ulceration30,34,36,39.

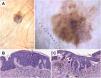

Histopathological correlation in pigmented actinic keratosis with areas of in situ squamous cell carcinoma. A) Pigmented atypical lesion on the temple of a 75-year-old woman. Dermoscopic image shows homogeneous brown pigmentation regions, brown circles, blue-gray granules, and gray dots arranged in lines in the lower part of the lesion. In this case, dermoscopic findings are not suitable to establish a reliable diagnosis, making histopahological examination essential. B) Histopathological image of an area of in situ squamous cell carcinoma (Bowen's disease) with melanophages on the superficial dermis (hematoxylin and eosin, ×10). C) Area of proliferative actinic keratosis with pigmented keratinocytes and melanophages on the superficial dermis (hematoxylin and eosin, ×10).

In iSCC, we can identify dermoscopic criteria associated with keratinization (white clods and circles, white structureless areas), vascular criteria (linear irregular vessels, dotted/glomerular vessels, and “hairpin” vessels), and other criteria (ulceration, hemorrhages).

In well-to-moderately differentiated SCC, keratin-associated criteria are predominant, while in poorly differentiated SCC, a polymorphous vascular pattern predominates (Fig. 6).

Keratoacanthoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma. A) Keratoacanthoma on the chest of a 54-year-old man. Dermoscopy shows a central keratin mass, white clods and circles, white structureless areas, and “hairpin” vessels with a radial distribution. B) Well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma on the leg of an 88-year-old woman. Dermoscopy shows white-yellowish structureless areas, white clods and circles, a polymorphous vascular pattern, and hemorrhages. C) Poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma on the arm of an 89-year-old woman. Dermoscopy shows a predominance of red color and an overtly atypical vascular pattern, with few keratin-associated criteria.

In the differential diagnosis with AK, the presence of dotted/glomerular vessels, “red starburst,” “hairpin” vessels, white structureless areas, and perifollicular white circles should prompt a skin biopsy to rule out iSCC.

The study by Zalaudek et al. of 78 iSCCs and 24 KAs reported that “hairpin” vessels (38.5%), linear irregular vessels (17.9%), targetoid (41%), white structureless areas (42.3%), central keratin (39.4%), and ulceration (17.9%) were significantly associated with the diagnosis of iSCC (p<0.001), with similar frequencies in the KA group except for linear irregular vessels, which were more common in the latter.10 On the other hand, Jaimes et al. coined the term “keratin pearls” after studying a total of 15 well-differentiated KAs/SCCs and observed that all lesions exhibited rounded white/yellowish structures surrounded by a whitish halo40 (Fig. 7). These structures, also known as white clods, were present in 25.6% and 16.7% of KA and SCC cases in the study by Rosendahl et al., respectively. This study, designed as a retrospective and prospective study with 43 KAs/60 iSCCs and 29 KAs/32 iSCCs/145 other lesions, respectively, concluded: 1) central keratin was more common in KA (51.2%) vs iSCC (30.0%) (p=0.03); 2) the presence of keratin was more common in the KA/iSCC group vs other lesions (78.7% vs 30.3%; p<0.001), with a sensitivity rate and positive predictive value (PPV) of 79% and 92% vs the BCC group, respectively; 3) white structureless areas (39.3% vs 18.6%; p=0.02) and white circles (44.3% vs 13.1%; p<0.001) were more common in the KA/iSCC group, with an 87% specificity rate for the latter vs other lesions; and 4) in the multivariate model, keratin, hemorrhages, and white circles were the only independent predictors of KA/iSCC diagnosis, with the latter reaching the highest ORs atv6.1 (95%CI, 2.4-13.3; p<0.001).41 In this context, of note that iSCC and KA can exhibit overlapping dermoscopic patterns, meaning that histopathological examinations will be necessary in most cases.42

Histopathological correlation in microinvasive squamous cell carcinoma. A) Erythematous papule on the chest of a 46-year-old man. B) Dermoscopic image shows white clods and a polymorphous vascular pattern with linear irregular, “hairpin,” and glomerular vessels. C) Histopathological image shows epithelial proliferation with acanthosis and bulbous nests, revealing acantholysis and central keratinization phenomena (hematoxylin and eosin, ×2). D) Higher magnification image showing tumor cells and keratinization areas (“horn pearls”), corresponding to the white clods seen in dermoscopy (hematoxylin and eosin, ×5).

Based on the degree of tumor differentiation, several dermoscopic patterns can be observed.43,44 In summary, well-to-moderately differentiated iSCCs will more frequently exhibit “hairpin” vessels, white or yellowish structureless, white clods, and circles. Specifically, KA has been associated with the presence of a central keratin mass surrounded by “hairpin” or linear irregular with a radial distribution.10,28 Conversely, poorly differentiated tumors will predominantly exhibit a polymorphous/atypical vascular pattern and ulceration.5 Lallas et al. found that the predominance of red color was associated with a 13-fold greater likelihood of being a poorly differentiated iSCC.44 A similar pattern with predominant atypical vascularization has been reported in combined SCC/Merkel cell carcinoma tumors45.

Regarding locations, we should mention that lip SCC shares most dermoscopic characteristics with cutaneous SCC.46 Benati et al. published a series of cases of 22 lip SCC, in which the most relevant structures were scales (100%), perivascular white halos (86%), white structureless areas (91%), white circles (59%), and a polymorphous vascular pattern (68%).47 In a recent multicentric retrospective study of 177 lip lesions (107 of them SCC), Lallas et al. saw that the presence of white clods and ulceration were predictors of SCC diagnosis vs controls (OR, 6.38 and 4.11, respectively).48

On the differential diagnosis with other lesions, early detection of iSCC and its differentiation from AK is essential, a common scenario in the follow-up of patients with actinic damage. The “red starburst” described by the study of Zalaudek et al. was observed in 29.5% of iSCC cases, with no significant differences being reported in frequency vs BD/in situ SCC. In any case, this dermoscopic pattern should be considered when planning to perform a skin biopsy in the context of a patient with actinic damage.10 Papageorgiou et al. collected 50 incipient cases of iSCC and 45 AK with histopathological confirmation and found that the presence of dotted/glomerular vessels (OR, 3.83), “hairpin” vessels (OR, 12.12), and white structureless areas (OR, 3.58) were the main predictors for SCC diagnosis on the multivariate analysis. The univariate model also suggested that since ulceration, perivascular white halos, and white circles could be predictors of SCC, therefore, they should also be taken into consideration.49 iSCC can also significantly overlap with common benign lesions, such as irritated seborrheic keratosis (ISK), particularly in the case of well-differentiated SCC.50 A study conducted by the same group analyzed 104 cases of SCC and 61 ISK and observed that the presence of dotted vessels (OR, 10.4), branched linear vessels (OR, 5.3), white structureless areas (OR, 6.78), white circles (OR, 23.45), or an irregular (OR, 2.55) or peripheral (OR, 2.8) distribution of vascular structures were predictors of SCC diagnosis vs ISK.51

ConclusionsPatients with actinic damage/field cancerization generally present with several skin lesions of varying biological behavior. In this context, an accurate differential diagnosis that allows us to select malignant lesions amenable to surgery and reliably identify “premalignant” lesions amenable to other treatments is desirable. Based on the available evidence, dermoscopy can be key in this endeavor, and therefore, appropriate training beyond melanocytic neoplasms, integrating the spectrum of keratinocytic carcinomas, is essential.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

We wish to thank Dr. Mar García, from Hospital Clínico Universitario “Lozano Blesa” Pathology Department for her invaluable collaboration with the histopathological correlation images.