Pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) is a rare skin disease characterized by slowly progressive red-to-brown erythematous papules with central scaling. Although some cases have been reported in conjunction with viral illnesses, the etiology of PLC is uncertain.1 COVID-19 is an ongoing global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2.2,3 We present a case of PLC that developed shortly after COVID-19 confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

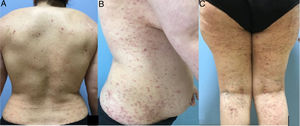

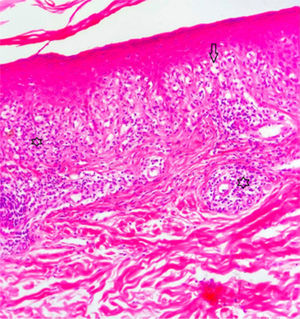

A 42-year-old woman presented with pruritic lesions that had appeared over the course of 5 months. Skin examination showed extensive areas of erythematous-purple lichenoid papules and plaques on the trunk and extremities (Fig. 1A–C). The oral and genital mucosa and nails were normal. The patient reported that she had been diagnosed with PCR-confirmed COVID-19 just 10 days before the lesions had appeared. She had not been hospitalized for COVID-19, but did receive treatment with favipiravir and analgesics. The information provided was confirmed by consulting the local COVID-19 database. The infection subsided within 5 days, and the skin lesions began to appear shortly afterwards. The patient did not consult a doctor, as she hoped that the lesions would disappear on their own. The relationship between COVID-19 and the skin lesions was not therefore recorded at the time, which is a weakness of this report. The differential diagnosis included lichen planus, lichenoid drug eruption, PLC, atypical pityriasis rosea, and prurigo. Histopathologic examination showed hyperkeratosis, irregular acanthosis, focal spongiosis, lymphocyte exocytosis in the epidermis, and a band-like lymphocytic infiltrate and melanophages in the superficial dermis (Fig. 2). Based on the clinical and histologic findings, the patient was diagnosed with PLC and treated with oral doxycycline, topical corticosteroids, and emollients. The lesions did not improve after 1 month of doxycycline, and the patient was started on narrowband UV-B therapy.

Three pathogenic mechanisms have been proposed for PL in the literature: an inflammatory reaction triggered by infectious agents, an inflammatory response secondary to T-cell dyscrasia, and immune complex–mediated hypersensitivity vasculitis. PL has been described in association with several infectious agents, namely, Toxoplasma gondii, Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, cytomegalovirus, parvovirus B19, staphylococci, and β-hemolytic streptococci.4 An association with vaccines has also been speculated. Filippi et al.5 recently described a case of PL triggered by the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine. Cutaneous manifestations associated with COVID-19 have been divided into 6 clinical patterns: an urticarial rash, a morbilliform rash, papulovesicular exanthem, a chilblain-like acral pattern, a livedo reticularis-like pattern, and a purpuric-vasculitic pattern.2 Other skin manifestations, such as petechiae, cutaneous mottling, eruptive cherry angioma, violaceous macules with porcelain-appearance, non-necrotic or necrotic purpura, aphthous ulcers, purpuric exanthema, telogen effluvium, and relapsing livedo reticularis are also defined as less commonly seen dermatological findings of COVID-19.6 To our knowledge, PLC has not yet been reported in association with COVID-19. Oral antibiotics (tetracycline, erythromycin), topical corticosteroids, and calcineurin inhibitors are recommended as the initial treatment for PLC. Narrowband UV-B/psoralen plus UV-A phototherapy may be considered as a second-line treatment for more resistant disease, followed by methotrexate, acitretin, dapsone, cyclosporine, or a combination of these.4

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.