Hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (HICC), or Lyral®, is a fragrance marker that is part of the Fragrance Mix II (FM II) and is still patched as an independent allergen within the European and other baseline series despite the European Commission banning its use in cosmetics in 2021.

We aimed to study the prevalence of sensitization to the HICC in Spain and its simultaneous positivity with the FM II to determine whether it should be part of the Spanish baseline series.

Material and methodWe analyzed all consecutive patients simultaneously patch-tested with HICC and FM II within the Spanish Contact Dermatitis Registry (REIDAC) from June 1st, 2018 to December 31st, 2023.

ResultsA total of 96 (0.8%) out of 12,029 patients analyzed yielded positive to HICC and 396 (3.3%) to FM II. In 53% and 64% of the patients, respectively, findings were considered currently relevant. A total of 72 out of 96 (75%) HICC positives would be detected if only FM II was patched.

ConclusionsPrevalence of HICC sensitization in Spain is low and has decreased in recent years. HICC is a prohibited fragrance in cosmetics and FM II detects 3 in 4 sensitized patients. Our results suggest that HICC should remain outside the Spanish baseline series and support its exclusion from the European baseline series.

El hidroxiisohexil 3-ciclohexeno carboxaldehído (HICC), o Lyral®, es un marcador de fragancias que forma parte de la mezcla de fragancias II (MF II), y aún se parchea como alérgeno independiente dentro de la batería estándar europea y otras baterías nacionales, pese a que la Comisión Europea prohibió su uso en cosméticos en el año 2021. Nuestro objetivo es estudiar la prevalencia de sensibilización al HICC en España y la positividad simultánea con la MF II, para determinar si debería formar parte de la batería estándar española.

Material y métodoAnalizamos todos los pacientes consecutivos del Registro Español de Investigación en Dermatitis de Contacto y Alergia Cutánea (REIDAC) parcheados simultáneamente con HICC y MF II, desde el 01 de junio de 2018 al 31 de diciembre de 2023.

ResultadosDe 12.029 pacientes analizados, 96 (0,8%) fueron positivos al HICC y 396 (3,3%) a la MF II, con una relevancia presente del 53 y 64%, respectivamente. Setenta y dos de los 96 (75%) pacientes sensibilizados al HICC serían detectados si solamente se parchease la MF II.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de sensibilización al HICC en España es baja y ha disminuido en los últimos años. El HICC es una fragancia prohibida en cosméticos y la MF II detecta a 3 de cada 4 pacientes sensibilizados. Nuestros resultados sugieren que el HICC debe permanecer fuera de la batería estándar española y apoyan su exclusión de la batería estándar europea.

Hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (HICC) (CAS no. [31906-04-4]) or Lyral® is a synthetic fragrance that is patch-tested independently (5% pet.) or as part of the fragrance mix II (FM II) within the European baseline series of patch tests,1 and also as part of fragrance series in patients with suspected allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). FM II (14% pet.) is composed of a total of 6 fragrances: hexyl cinnamic aldehyde (5% pet.), HICC (2.5% pet.), coumarin (2.5% pet.), farnesol (2.5% pet.), citral (1% pet.), and citronellol (0.5% pet.). Because of their importance, HICC and FM II were added as allergens to the European baseline series in 2008.2 In Spain, both have been included as allergens in the Spanish baseline series since 2012,3 although HICC was removed from the Spanish baseline series in 2022, becoming part of the Spanish extended series.4

The most recent European studies indicate a decrease in the prevalence of sensitization to HICC in recent years, currently around 1%.5–9 In most studies, the percentage of HICC-positive patients who would be missed if only FM II were patch-tested within a baseline series is approximately 15–20%. For this reason, some authors have recommended eliminating HICC from European and national baseline series.8–13

The primary endpoint of this study is to evaluate the frequency of sensitization to HICC in Spain during the period 2018–2023 and the simultaneous positivity to FM II to determine whether HICC should remain part of the Spanish baseline series. Secondary endpoints include assessing the clinical relevance of sensitization and the clinical–epidemiological characteristics of the sensitized population.

Materials and methodsThe Spanish Registry of Research in Contact Dermatitis and Cutaneous Allergy (REIDAC) prospectively collects clinical information from all patients studied with patch tests in participating hospitals in Spain.14 We conducted an observational, cross-sectional study including unselected patients from REIDAC, consecutively and simultaneously patch-tested with HICC (5% pet.) and FM II (14% pet., of which 2.5% is HICC), as part of the Spanish baseline and the 2022 Spanish extended series, from June 1st, 2018 to December 31st, 2023.

Allergens were obtained from Chemotechnique Diagnostics® (Vellinge, Sweden) and allergEAZE® (SmartPractice, Calgary, Canada), depending on center availability. Patch tests were performed according to the clinical practice guidelines of the European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD).15 Reactions scored as (+), (++), or (+++) were considered positive. Relevance (current, past, irritant, active sensitization, cross-reactivity, unknown) was determined based on clinical history. Data collected included MOAHLFA index variables (Male, Occupational dermatitis, Atopic dermatitis, Hand dermatitis, Leg dermatitis, Face dermatitis, Age>40 years), the patient's main occupation, and the main site of dermatitis.

Continuous variables (age) were expressed as arithmetic mean (standard deviation), and categorical variables as counts (proportions). Fisher's exact test was used as univariate analysis to study the association between MOAHLFA variables and positivity to HICC and FM II, expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI). Results were considered significant when p≤0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata® 16 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata® Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC, RRID: SCR_012763).

ResultsSensitization and relevanceA total of 12,029 unselected patients were studied (Table 1). The overall rate of sensitization to HICC was 0.8% (96/12,029). Of these, 53.1% (51/96) were of current relevance. The overall frequency of sensitization to FM II was 3.3% (396/12,029), of which 64.4% (255/396) were of current relevance. The proportion of weak (+), moderate (++), and strong (+++) reactions was similar in both groups.

Frequency of positives and relevance to hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde and Fragrance Mix II.

| Reactions | Relevance | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | ||||||||||||

| All (%a) | + (%b) | ++ (%b) | +++ (%b) | Irritant (%a) | Doubtful ?+ (%a) | Current (%) | Past (%) | Irritant (%) | Active sensitization (%) | Cross-reactivity (%) | Unknown (%) | |

| HICC | 96 (0.8) | 40 (41) | 43 (45) | 13 (14) | 1 (0.01) | 14 (0.1) | 51 (53.1) | 13 (13.5) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 31 (32.3) |

| FM II | 396 (3.3) | 176 (44) | 172 (43) | 48 (12) | 1 (0.01) | 52 (0.4) | 255 (64.4) | 27 (6.8) | 11 (2.8) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 100 (25.3) |

HICC: hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde; FM II: Fragrance Mix II.

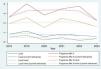

The annual frequency of sensitization to HICC ranged between 0.56% and 1.14%, with no significant variation (p=0.059) (Fig. 1). Considering only cases of current relevance, the frequency ranged between 0.15% and 0.50%, with a significant decreasing trend over time (p=0.026). The annual frequency of sensitization to FM II went from 2.26% to 4.02%, without significant variation (p=0.081). Considering only cases of current relevance, the frequency ranged between 1.53% and 2.56%, with no significant variation (p=0.170).

Annual variation in positivity frequency to hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde (Lyral) and fragrance mix II (FM II). Solid lines illustrate annual variation for all positives (Lyral: blue line; FM II: brown line) and positives with current relevance (Lyral: green line; FM II: orange line). Dashed lines illustrate trend variation for all positives (Lyral: green line; FM II: red line) and positives with current relevance (Lyral: blue line; FM II: yellow line).

Of HICC-positive patients, 75% (72/96) also tested positive to FM II (Table 2, Fig. 2). Considering only the subgroup with current relevance, 74.5% (38/51) of HICC-positive patients also tested positive to FM II.

Frequency of negatives and simultaneous positives to hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde and Fragrance Mix II.

| FM II | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negatives | Positives | ||

| HICC | |||

| Negatives (%a) | 11,609 (97.3) | 324 (2.7) | 11,933 |

| Positives (%b) | 24 (25) | 72 (75) | 96 |

| Total | 11,633 | 396 | 12,029 |

HICC: hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde; FM II: Fragrance Mix II.

Of FM II-positive patients, 18.2% (72/396) also tested positive to HICC. Considering only the subgroup with current relevance, 14.9% (38/255) of FM II-positive patients also tested positive to HICC.

Factors associated with positivity to HICC and FM IIThe MOAHLFA index of HICC-positive patients was similar to that of FM II-positive patients (Tables 3 and 4). Sensitization to HICC was not significantly associated with any MOAHLFA variable (Table 3). FM II positivity was significantly associated with higher frequency of age>40 years (p=0.002) and lower frequency of facial involvement (p=0.001). Considering only the subgroup of patients with current relevance, FM II positivity was significantly associated with higher frequency of age>40 years (p=0.024) and lower frequency of facial involvement (p=0.028) (Table 4).

Population characteristics and odds ratios for positivity to hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde.

| HICC, all patch-tested (%) | HICC, negatives (%) | HICC, positives (%) | OR (95%CI) | HICC, positives with current relevance (%) | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12,029 (100) | 11,933 (99.2a) | 96 (0.8a) | 51 (0.4a) | ||

| MOAHLFA | ||||||

| Sex (M) | 3635 (30) | 3610 (30) | 25 (26) | 0.8 (0.5–1.3) | 15 (29) | 1.0 (0.5–1.8) |

| Occupational (O) | 1069 (9) | 1066 (9) | 3 (3) | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) | 1 (2) | 0.2 (0.03–1.5) |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | 2228 (19) | 2207 (19) | 21 (22) | 1.2 (0.75–2) | 12 (24) | 1.3 (0.7–2.6) |

| Hand location (H) | 3721 (31) | 3698 (31) | 23 (24) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) | 11 (22) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) |

| Leg location (L) | 609 (5) | 607 (5) | 2 (2) | 0.4 (0.1–1.6) | 2 (4) | 0.8 (0.2–3.1) |

| Face location (F) | 2869 (24) | 2849 (24) | 20 (21) | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 11 (22) | 0.9 (0.45–1.7) |

| Age>40 years (A) | 8124 (68) | 8057 (68) | 67 (70) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 30 (59) | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) |

| Mean age (SD) | 48.4 (18.3) | 48.4 (18.0) | 48.4 (18.6) | 1.0 (0.99–1.01) | 47.2 (15.4) | 1.0 (0.98–1.01) |

| Main occupation | ||||||

| Administrative | 1341 (11) | 1314 (11) | 27 (28) | 14 (27) | ||

| Service sector | 607 (5) | 595 (5) | 12 (13) | 6 (12) | ||

| Retired | 2091 (17) | 2079 (17) | 12 (13) | 5 (10) | ||

| Homemaker | 1151 (10) | 1145 (10) | 6 (6) | 4 (8) | ||

| Health care | 897 (7) | 892 (7) | 5 (5) | 4 (8) | ||

| Other/unknown | 5942 (49) | 5908 (50) | 34 (35) | 18 (35) | ||

| Main site of dermatitis | ||||||

| Hands | 3721 (31) | 3698 (31) | 23 (24) | 11 (22) | ||

| Legs | 609 (5) | 607 (5) | 2 (2) | 2 (4) | ||

| Face | 2869 (24) | 2849 (24) | 20 (21) | 11 (22) | ||

| Trunk | 1868 (16) | 1847 (16) | 21 (22) | 14 (27) | ||

| Neck | 350 (3) | 343 (3) | 7 (7) | 5 (10) | ||

| Other/unknown | 2612 (22) | 2589 (22) | 23 (24) | 8 (16) | ||

SD: standard deviation; HICC: hydroxyisohexyl 3-cyclohexene carboxaldehyde; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MOAHLFA: Male, Occupational dermatitis, Atopic dermatitis, Hand dermatitis, Leg dermatitis, Face dermatitis, Age>40; OR: odds ratio.

Population characteristics and odds ratios for positivity to Fragrance Mix II.

| FM II, all patch-tested (%) | FM II, negatives (%) | FM II, positives (%) | OR (95%CI) | FM II, positives with current relevance (%) | OR (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 12,029 (100) | 11,633 (96.7a) | 396 (3.3a) | 255 (2.1a) | ||

| MOAHLFA | ||||||

| Sex (M) | 3635 (30) | 3506 (30) | 129 (33) | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 87 (34) | 1.2 (0.9–1.6) |

| Occupational (O) | 1069 (9) | 1032 (9) | 37 (10) | 1.1 (0.75–1.5) | 22 (9) | 1.0 (0.6–1.5) |

| Atopic dermatitis (A) | 2228 (19) | 2160 (19) | 68 (17) | 0.9 (0.7–1.2) | 42 (17) | 0.9 (0.6–1.2) |

| Hand location (H) | 3721 (31) | 3597 (31) | 124 (31) | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 68 (27) | 0.8 (0.6–1.1) |

| Leg location (L) | 609 (5) | 585 (5) | 24 (6) | 1.2 (0.8–1.85) | 18 (7) | 1.4 (0.9–2.3) |

| Face location (F) | 2869 (24) | 2804 (24) | 65 (16) | 0.6 (0.5–0.8) | 46 (18) | 0.7 (0.5–0.96) |

| Age>40 years (A) | 8124 (68) | 7829 (68) | 295 (75) | 1.4 (1.1–1.8) | 189 (74) | 1.4 (1.04–1.85) |

| Mean age (SD) | 48.4 (18.3) | 48.3 (18.0) | 51.1 (17.7) | 1.0 (1.00–1.01) | 50.9 (18.8) | 1.0 (1.00–1.01) |

| Main occupation | ||||||

| Administrative | 1341 (11) | 1283 (11) | 58 (15) | 39 (15) | ||

| Service sector | 607 (5) | 586 (5) | 21 (5) | 12 (5) | ||

| Retired | 2091 (17) | 2005 (17) | 86 (22) | 52 (20) | ||

| Homemaker | 1151 (10) | 1128 (10) | 23 (6) | 17 (7) | ||

| Health care | 897 (7) | 865 (7) | 32 (8) | 17 (7) | ||

| Other/unknown | 5906 (49) | 5766 (50) | 140 (35) | 137 (54) | ||

| Main site of dermatitis | ||||||

| Hands | 3721 (31) | 3597 (31) | 124 (31) | 68 (27) | ||

| Legs | 609 (5) | 585 (5) | 24 (6) | 18 (7) | ||

| Face | 2869 (24) | 2804 (24) | 65 (16) | 46 (18) | ||

| Trunk | 1868 (16) | 1785 (15) | 83 (21) | 61 (24) | ||

| Neck | 350 (3) | 334 (3) | 16 (4) | 11 (4) | ||

| Other/unknown | 2612 (22) | 2528 (22) | 84 (21) | 51 (20) | ||

Statistically significant variables (p≤0.05) are italicized.

SD: standard deviation; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; MOAHLFA: Male, Occupational dermatitis, Atopic dermatitis, Hand dermatitis, Leg dermatitis, Face dermatitis, Age>40; OR: odds ratio.

The prevalence of sensitization to HICC in our study was 0.8%, lower than the 1.1% observed by Silvestre et al. in 2011–2015.16 In contrast, the frequency of FM II positivity remained stable at 3.3%.

In 1999, Frosch et al.17 recommended routine patch testing of HICC, and in 2005 defended the utility of FM II to detect more fragrance-sensitized patients,18 which led Bruze et al. to recommend inclusion of both in the European baseline series in 2008.2 Since then, European studies in consecutive patients have shown a progressive decrease in HICC positivity and, to a lesser extent, FM II positivity, with current prevalences near 1% and 3%, respectively.5–9 This decrease relates to the 2009 recommendation of the International Fragrance Association (IFRA) to reduce HICC concentration in cosmetics19 and the European Commission's definitive ban on its use in cosmetics in 2017, effective August 23rd, 2021.20

Significant variability exists in the prevalence of allergy to fragrance markers across European centers.21 Within the Information Network of Departments of Dermatology (IVDK), Geier et al.,6,22 Uter et al.,23 Krautheim et al.,24 and Schnuch et al.25,26 demonstrated a decline in HICC and FM II positivity from 2.6% and 5% in 1995 down to 1.1% and 3% in 2021, respectively. Similarly, though less markedly, HICC sensitization decreased significantly in the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies (ESSCA), as shown by Uter et al.,7,27,28 Ahlström et al.,8 and Frosch et al.,29 from 1.7% in 2009 down to 1.3% in 2020, with FM II remaining stable at 3.8%. In an International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (ICDRG) study from 2012 to 2016, Bruze et al.9 found HICC and FM II positivity frequencies of 1.6% and 3.9%, respectively. In another multicenter European cohort (2008–2011), Diepgen et al.30 observed respective frequencies of 1.5% and 1.9%.

In Sweden, HICC and FM II allergy prevalence was studied by Andernord et al.,31 Engfeldt et al.,12 and Isaksson et al.10 within the Swedish Contact Dermatitis Research Group (SCDRG), and by Sukakul et al.13 and Mowitz et al.32 in Malmö Hospital, decreasing from peaks of 1.7% and 3.4% in 2006 down to lows of 1% and 2.3% in 2020, respectively. Within SIDAPA (Società Italiana Dermatologia Allergologica Professionale Ambientale) during 2016–2021, Stingeni et al.5 reported respective prevalences of 1% and 2.1%. At Gentofte Hospital (Copenhagen, Denmark), Ahlström et al.8 observed a decrease in HICC sensitization from >2% in 2009 down to 1% in 2019. At St. John's Hospital (London, UK), Mann et al.33 and Ung et al.34 found HICC and FM II prevalences stable at 1.4% and 2.9%, respectively. At Leuven Hospital (Belgium), Nardelli et al.35 observed decreasing HICC sensitization from 2007 to 2011 (mean 2.1%), while FM II remained stable (mean 6%).

In our study, allergy to HICC and FM II was clinically relevant in over half of patients, which is consistent with prior reports.2,8,21,30 The proportion of moderate/strong (++/+++) reactions was 58% and 56% for HICC and FM II, respectively, with low rates of irritant/doubtful reactions.

Of all HICC positives, 75% were detected by FM II, a percentage similar to that observed in cases with clinically relevant allergy to both allergens. In the literature, the proportion of FM II-positive, HICC-negative patients ranges from 10%34,35 to 24%,5,8,29 averaging 15–20% in most studies.9,10,12,22,24 Given these findings and the decline in HICC sensitization, several authors have advocated removal of HICC from national and European baseline series (except Stingeni et al.5). Indeed, the SCDRG eliminated HICC from the Swedish baseline series in 2014,10 and the ICDRG adopted the same decision for the ICDRG baseline series in 2020.11 This ultimately led to exclusion of HICC from the new 2022 Spanish baseline series,4 moving it to the Spanish extended series—a decision supported by our findings. Considering the European Commission's ban on HICC in cosmetics,36 sensitization is expected to continue declining. Nonetheless, to continue documenting this trend and given the lack of regulation of HICC use in cosmetics in non-European markets, we recommend continuing HICC patch testing within the Spanish and European extended series.

In our study, no MOAHLFA variables were associated with HICC positivity, while FM II positivity was significantly associated with age>40 years and inversely with facial dermatitis. In the literature, female sex and age>40 years are often associated with positivity to HICC5,8,10,25,29,30,37 and FM II.5,10,24,38 Occupational dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, and facial dermatitis have been occasionally associated with HICC8,37 and FM II.6,24,38 In our patients, the most frequent sites were hands, trunk, and face for both HICC (Table 3) and FM II (Table 4), consistent with fragrance ACD typically affecting hands, face, neck, and axillae.21,38,39 Interestingly, in our cohort facial dermatitis was negatively associated with FM II positivity, possibly because we only analyzed the main site without considering multiple locations. Additionally, several studies link hand involvement with FM II positivity,6,16,24,38 while leg involvement has been negatively associated with HICC sensitization.8,16,25,37,40

In our population, occupational ACD cases were rare, at 3% for HICC and 10% for FM II. The most frequent occupations were administrative staff, service sector employees, homemakers, and healthcare workers, with no major differences by relevance (Tables 3 and 4). In general, occupational ACD due to fragrances is uncommon, mainly involving the perfume/cosmetics, domestic cleaning, esthetics/hairdressing, health care, food, metalworking, and aromatherapy industries.21,39 However, Montgomery et al.41 observed a gradual increase in occupational fragrance ACD cases reported in the UK during 1996–2015.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of sensitization to HICC in Spain has decreased in recent years, currently standing at 0.8%. Half of the cases are clinically relevant. FM II detects 3 of every 4 patients sensitized to HICC. Our results support keeping HICC outside the Spanish baseline series and within the Spanish extended series and highlight the need to consider its transfer from the European baseline series to the European extended series.

FundingREIDAC is promoted by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV, Fundación Piel Sana), which has received funding from the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS) (BOE reference) and Sanofi®. The funding sources had no role in study conception, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript preparation, review, approval, or logistical support.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.

The authors thank Dr. Francisco Javier Ortiz de Frutos (Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain) for providing data from his center, and Ms. Marina de Vega (AEDV Research Unit) for her support in maintaining the registry. This work is part of the doctoral thesis of Carlos Pelayo Hernández Fernández at Universidad de Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC) (Canary Islands, Spain).