An 81-year-old woman was referred for an edematous, erythematous plaque that had arisen 48h earlier in the right periorbital region and on the ipsilateral side of the face. The lesions, present on both cheeks, initially had a papular-vesicular appearance, but they subsequently increased in size and became firm and tender and evolved rapidly into edematous plaques. The patient reported pruritus and fever of 38°C. There was no history of insect bite, trauma, foreign travel, or gastrointestinal problems in the previous months. The patient was not taking any regular medication, including topical medication, at the time of onset of the lesions, nor did she use cosmetic preparations or contact lenses.

Three years earlier she had attended the infectious diseases department with a sore, pruritic erythematous plaque affecting the whole left side of the face, associated with fever. Antimicrobial therapy with intravenous amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid had been administered and the lesion resolved within a week, without scarring. A diagnosis of a probable acute bacterial cellulitis had been made. There was no other medical history of note and her family history was unremarkable.

On physical examination, the patient had a healthy appearance, was afebrile, and presented a tender, infiltrated erythematous plaque that affected the periorbital region and cheek on the right side of the face (Fig. 1). There were no palpable lymph nodes and no other skin lesions. The total IgE concentration was 1334kU/L (normal range, 0–100kU/L). Complete blood count, biochemistry, and serologic tests for antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and C1 inhibitor and C4 levels were normal or negative. Chest and sinus X-rays were normal. Facial computed tomography showed no ocular or intracranial alterations. Ophthalmologic examination was normal in both eyes and no ocular dysfunction was detected. Direct immunofluorescence for herpes viruses was negative.

The suspected clinical diagnosis was an insect bite reaction with acute cellulitis. The patient was treated with intravenous cloxacillin and the skin lesions improved within a few days.

Two weeks later, the patient had a recurrence, with the reappearance of an erythematous, edematous plaque in the right periocular area, associated with bullous papules on both arms and hands. These lesions were initially bright red, but progressively darkened to a violaceous color, giving the appearance of hematomas (Fig. 2). There was no malaise or fever. Laboratory studies were within normal limits, including the peripheral eosinophil count. The total IgE concentration was 910kU/L.

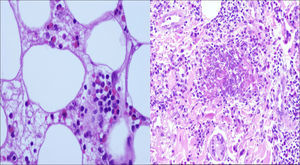

Histopathology study of a skin biopsy taken from the left wrist revealed marked edema of the papillary dermis with a moderately dense superficial and deep perivascular and interstitial infiltrate of eosinophils and lymphocytes throughout the dermis and subcutaneous fat. Additionally, degranulated material and fragmented eosinophils were observed around collagen fibers in the dermis and were identified as flame figures (Fig. 3). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. A diagnosis of Wells syndrome was made.

Oral steroid therapy was started at 0.5mg/kg/d and the patient's cutaneous signs and symptoms improved within 24h, leaving residual lesions. The dose of oral prednisone was tapered over 6 days. However, 10 days after withdrawal of the corticosteroid treatment, the patient presented recurrence in the form of edema in the left periorbital region and vesicles on forehead; there were no systemic symptoms at that time. A further cycle of oral steroids (prednisone 30mg/d) was administered, leading to a notable improvement, but a new flare-up occurred when the dose was reduced below 10mg a day. Oral prednisone, 10mg/d, was therefore continued for a month, with no adverse effects. At the end of that cycle, the lesions had cleared completely and the patient has subsequently remained symptom-free.

Wells syndrome is a rare dermatosis of unknown etiology and pathogenesis. It is typically characterized by recurrent episodes of pruritic plaques, occasionally associated with bullae, which develop over 2–3 days and usually resolve spontaneously over 2–8 weeks. The site and appearance of the skin lesions vary, but they often affect the limbs. Facial lesions are rare. In our patient, the periorbital region was the most severely affected area, alternating from right to left sides in successive recurrences.1–3

The most common systemic complaint is malaise. Fever is present in less than a quarter of cases. The manifestations of eosinophilic cellulitis are difficult to differentiate from bacterial cellulitis, and misdiagnosis is common. In our case, the first skin lesions were associated with fever, leading to a misdiagnosis of bacterial cellulitis. Although there was an initial improvement with antimicrobial therapy, we consider this as a coincidence and that the cutaneous lesions had probably undergone spontaneous remission.

Approximately 50% of cases reported in the literature have presented peripheral blood eosinophilia during active disease, but the eosinophil count remained normal in our patient.4–8

In conclusion, we have described a patient initially diagnosed with bacterial cellulitis, but in whom skin biopsy subsequently established a diagnosis of eosinophilic cellulitis. This occurred in the absence of any obvious trigger or associated skin conditions and showed a good response to steroid therapy. We would like to draw attention to the atypical periorbital site of the lesions.

We consider eosinophilic cellulitis should be included in the differential diagnosis of recurrent episodes of edema in the periorbital region (Table 1).8

Differential diagnosis of recurrent periorbital edema.a

| Infectious diseases | Cellulitis, erysipelas, herpesvirus infection trichinosis, rickettsiosis, anthrax, fungal infections, tungiasis, tularemia |

| Inflammatory and autoimmune diseases | Angioedema, urticaria Rosacea Allergic/irritant contact dermatitis Sweet syndrome Eosinophilic dermatoses Dermatomyositis, lupus erythematosus |

| Systemic diseases | Thyroid, kidney, liver, and heart diseases |

| Drugs and therapies | Imatinib, rifampicin, niacin, clozapine, ipilimumab, risperidone, aspirin, irbersartan, chlorpromazine Positive airway pressure ventilation |

The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.