In 1939, Hailey and Hailey described a previously undescribed cutaneous entity in four related patients with lesions that typically appeared in folds and worsened in summer, which they called “benign familial chronic pemphigus”.1

Currently known as “familial benign pemphigus (FBP)” or “Hailey–Hailey disease (HHD)”, it is a rare disease, with autosomal dominant inheritance, complete penetrance, and variable expressivity, due to mutation in the ATP2CA1 gene, which encodes a magnesium-dependent Ca2+ pump, sequestering Ca2+ inside the Golgi apparatus.2,3

It is a disease that generates high comorbidity in patients and for which there is still no standardized therapeutic algorithm. We present a clinical case of this entity, refractory to multiple treatments, and with a remarkable clinical response to the phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitor apremilast.

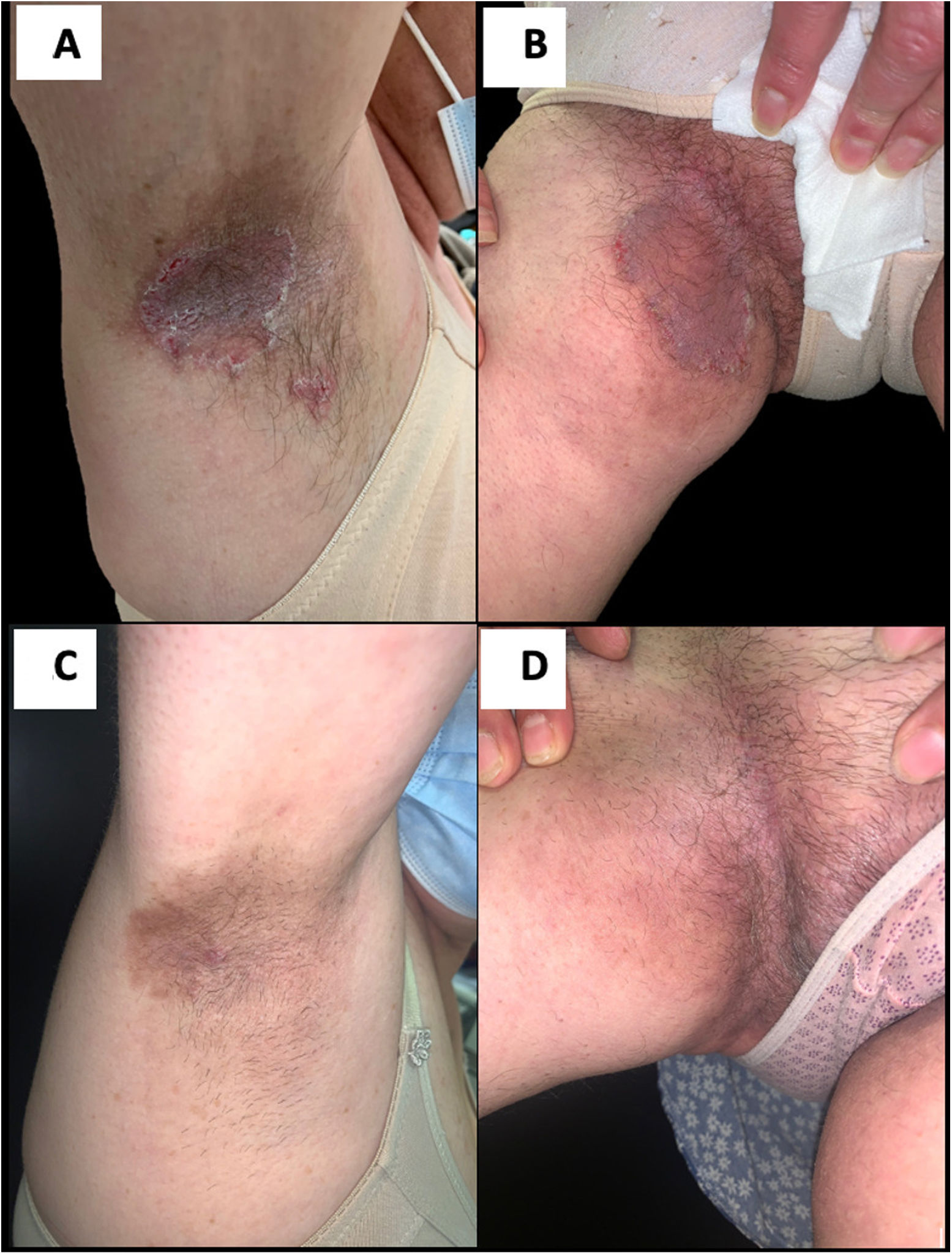

A 54-year-old female came to the Dermatology department for evaluation of skin lesions. She reported the presence of them since childhood (8–10 years) and their location in intertriginous areas. She denied family history and she did not have children. They were erythematous plaques, with well-defined borders, some superficial erosions, and which typically macerated every summer with foul-smelling exudate and secondary infection (Fig. 1A, B). Throughout her life, she had been treated with topical and systemic antibiotics, topical corticosteroids, and antiseptic measures, with unsatisfactory responses.

In an initial examination, samples of skin scales were taken from one of the axillary folds to rule out fungal infection (which were negative), blood tests (which were normal) and biopsy for microbiological study (which turned out to be negative) and anatomopathological exam. In the histopathological study, intraepidermal clefts were evidenced by extensive suprabasal acantholysis, with the characteristic “brick wall image in ruins”, due to discohesion of the keratinocytes. Likewise, important papillomatosis was evidenced with the presence of basal cells that constituted villi, which were projected into the light of the ampulla. A discrete perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate was seen in the superficial dermis. Immunofluorescence studies were negative.

Suspecting FBP, initial treatment with topical corticosteroids (methylprednisolone) and antibiotics (gentamicin) was started every 12h, until the biopsy result.

Subsequently, due to the poor evolution and already with the confirmatory result of the biopsy, the patient received 3 cycles of botulinum toxin, first administering 80 IU in each armpit and groin. The second and third administration of botulinum toxin (200 IU) was performed at 4 and 8 months, with no response.

Successively, the patient was progressively prescribed various therapeutic regimens over the following three years, all of them with unsatisfactory responses: cotrimoxazole, dapsone, photodynamic therapy, methotrexate, magnesium, naltrexone, laser therapy with carbon dioxide (CO2), etanercept, cyclosporine and oxybutynin.

Finally, it was decided to start rescue treatment with apremilast, initially with induction dose and later with maintenance dose of 30mg every 12h, with a very good response. A physical global assessment (PGA) scale was used to assess the efficacy of the treatment, with 0 indicating clear; 1, almost clear; 2, moderate improvement; 3, slight improvement; 4, no change; and 5, worsening of the disease. The baseline PGA score was 4, with rapid improvement (PGA 2 after one month of treatment with dose of 30mg every 12h) and sustained over time (PGA 1 at 3 and 6 months).

Likewise, the visual analog scale (VAS) of pain reported baseline levels of 8/10, with improvement to 4/10 at one month of treatment, from 2/10 at 3 months of treatment and 1/10 at 6 months.

Tolerance was good with no adverse effects reported.

FBP is a disabling clinical entity with poorly defined treatment to date.

In mild forms, topical treatment with antibiotics, corticosteroids and topical immunomodulators is usually started.4

In patients with moderate-severe disease, botulinum toxin has been postulated in recent years as first-line treatment.5 In recalcitrant cases, the therapeutic range is wide: antibiotics, retinoids, systemic immunomodulators, physical treatments (photodynamics, laser therapy. etc.), etc.6 Among these, apremilast, a PDE-4 inhibitor widely used for the treatment of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. It downregulates the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-12/23, IL-12, and increases anti-inflammatory IL-10 levels, which are implicated in FBP.7

In 2018, Kieffer J. et al.8 published the first cases of PBF treated with apremilast, and since then some case reports and series have been registered in the literature, with a generally favorable response and good side effect profile.

That is why we conclude with this article the convenience of including apremilast as part of the therapeutic arsenal for PBF. We believe that new evidence-based studies are necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflict of interest.