Quinacrine, or mepacrine as it is also known, is a synthetic quinine analog that was the drug of choice for malaria prevention during World War II.1 It was during this period that its effectiveness in the treatment of connective tissue diseases became obvious, when many soldiers taking the drug to prevent malaria experienced improvements in the symptoms of lupus and rheumatoid arthritis. With the advent of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, both of which proved to be more effective antimalarial agents, quinacrine fell into disuse.

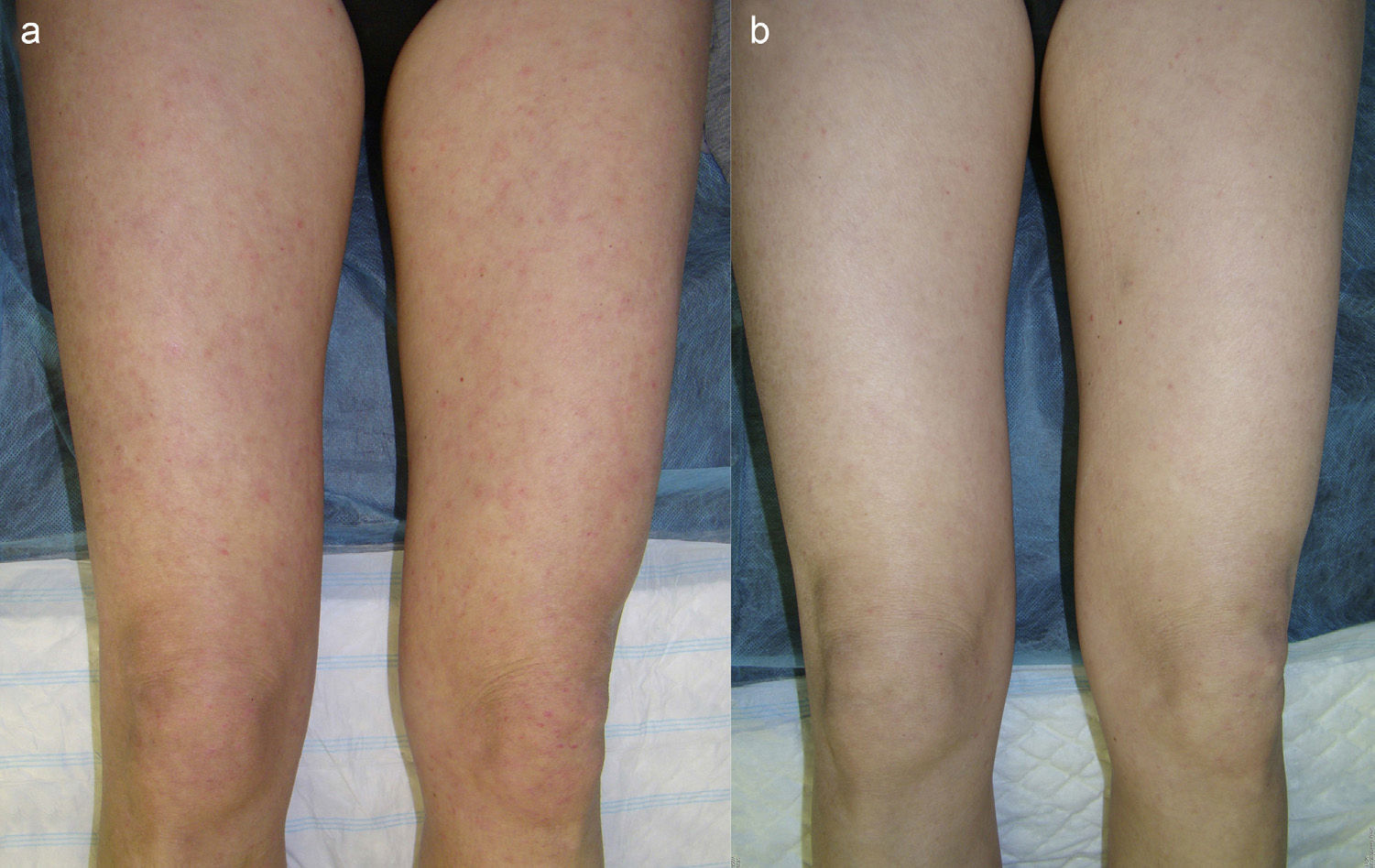

Clinical CasesThe patient, a 45-year-old woman (nonsmoker), had been diagnosed with cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) when she was 38 years of age. Six years later her condition met the criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Clinically, her condition was characterized by photosensitivity, malar eruption, scattered erythematous papules (Fig. 1a), and aphthous mouth ulcers. Laboratory test results revealed chronic lymphocytopenia and a positive antinuclear antibody titer of 1:640. Despite treatment with several different topical and systemic agents (prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and colchicine), the patient never achieved optimal control of the disease. Seven months ago, after quinacrine 100mg/d was added to her treatment regimen (colchicine 1mg/d and hydroxychloroquine 200mg/d), the patient experienced marked improvement in her skin lesions (Fig. 1b) and a decrease in the frequency and severity of disease flares. The only side effect was a slight yellowing of the skin and mucous membranes.

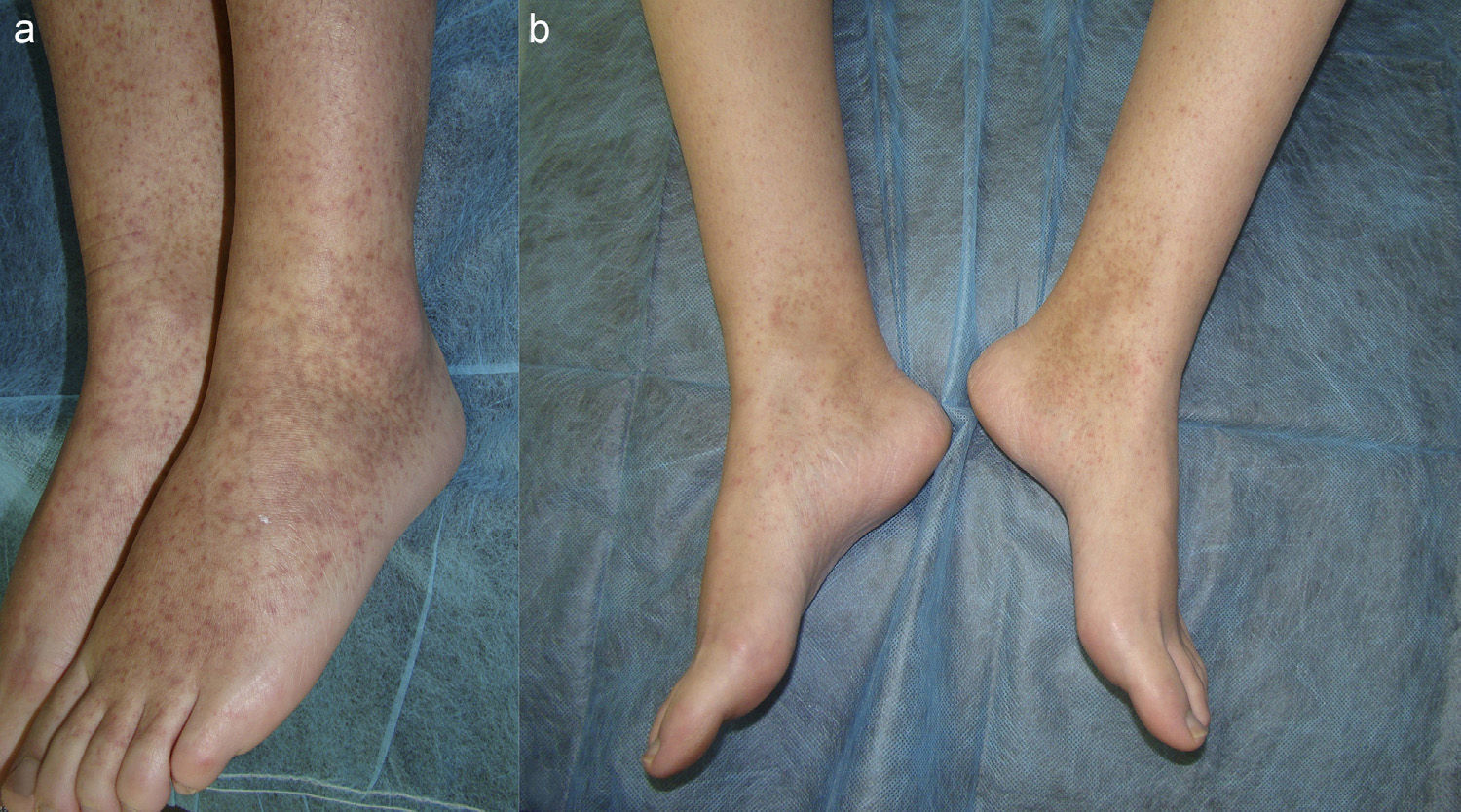

The second patient is a 35-year-old woman (smoker) with a history of chronic juvenile arthritis, who had been diagnosed with SLE at 26 years of age. She reported almost daily episodes of fever, frequent outbreaks of aphthous ulcers, arthritis, and vasculitis in the form of purpuric papules on the lower limbs (Fig. 2a). Laboratory test findings included a positive ANA value of 1:1280 and chronic leukopenia. The response to treatment with many different systemic agents (prednisone, hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, sulfones, rituximab, belimumab, and thalidomide) was poor. Twelve months ago, quinacrine 100 mg/d was added to the basic treatment regimen of hydroxychloroquine 200 mg/d. Since then, the patient has experienced considerable improvement in her condition (Fig. 2b), with a significant decrease in the number of flares and no adverse effects.

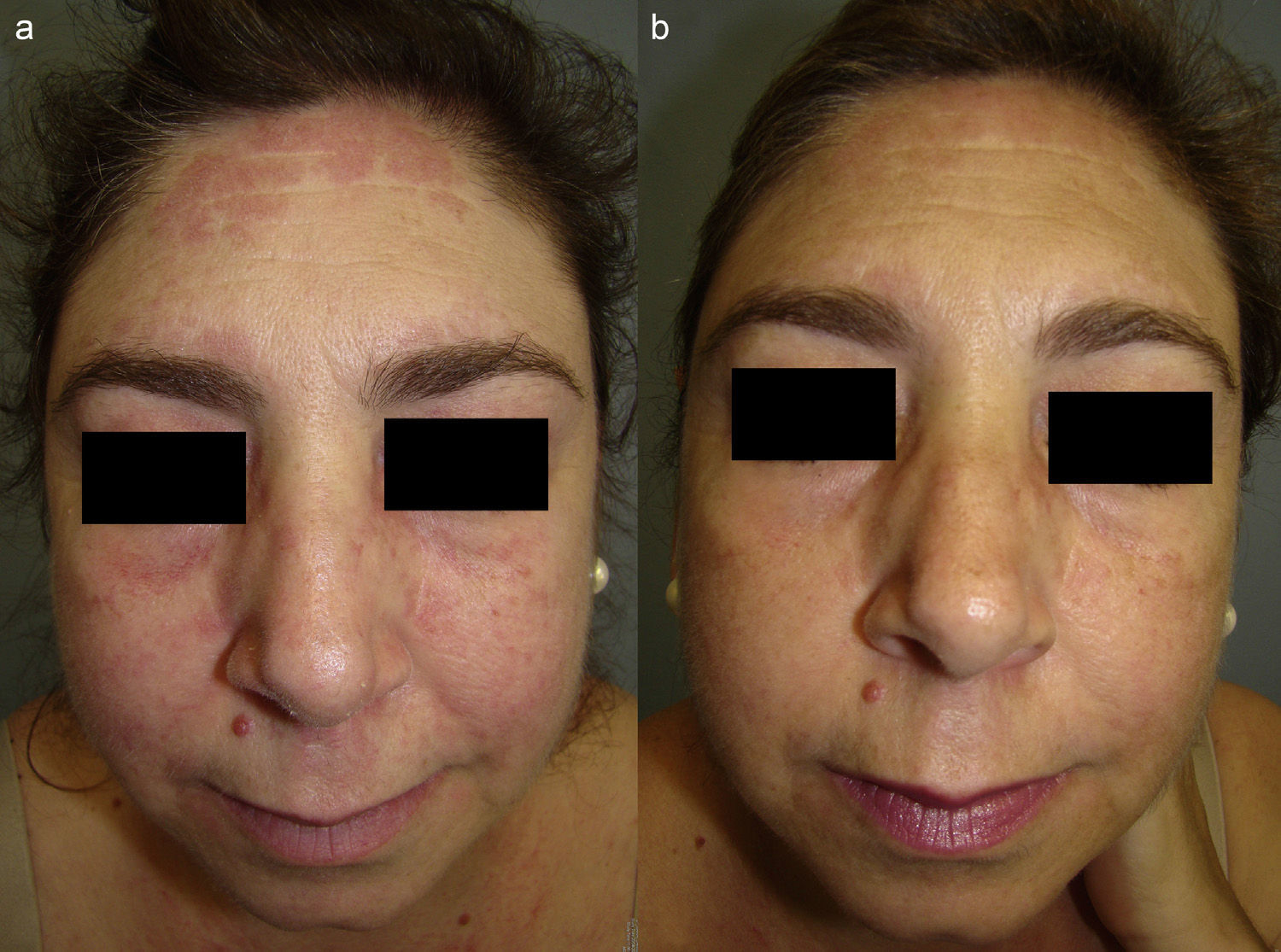

The third case involves a 47-year-old woman (smoker) diagnosed 4 years ago with amyopathic dermatomyositis (negative ANA, negative anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5, and negative transcriptional intermediary factor 1-γ). The salient clinical features in this case were photosensitivity, heliotrope erythema, and edematous erythematous plaques on the face (Fig. 3a), upper chest, elbows, and knees. The patient had undergone treatment with several systemic drugs (prednisone, methotrexate, azathioprine, and rituximab) with little improvement. Since she started a combination regimen of hydroxychloroquine 400mg/d, prednisone 5mg/d, and quinacrine 100mg/d some 7 months ago, the patient has experienced marked improvement in her skin lesions (Fig. 3b), with no adverse effects.

DiscussionThe usefulness of antimalarial agents in the treatment of connective tissue disorders has been amply demonstrated and the treatment of lupus is the setting in which the most evidence has been accumulated.2 The evidence shows that, in patients with lupus, antimalarial therapy not only reduces the number of disease flares and improves skin symptoms, but also improves glucose control and lipid profiles, has a potent antithrombotic effect, and is useful in the treatment and prevention of nephritis.3,4 Thus, antimalarial therapy significantly reduces the mortality of patients with different forms of lupus. However, the use of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine, the 2 best known and most often prescribed antimalarial agents is limited by certain drawbacks, including a lack of response to single-drug therapy and an association with retinal abnormalities. Owing to its chemical structure, quinacrine offers certain advantages over its analogs and can therefore prove very useful in certain cases. Several studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in combination with its analogs and reported good response rates in patients with refractory lupus5–9 or dermatomyositis.10

It is also important to highlight that quinacrine has no ocular toxicity, making it a suitable alternative for patients with retinopathy who are candidates for antimalarial therapy. The use of quinacrine has also recently been proposed as a way to reduce the accumulated dose of hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine in patients with lupus on long-term antimalarial therapy.2 The daily recommended dose of quinacrine is 100 mg, and the drug is available in this dosage.1 However, quinacrine can only be acquired in Spain by requesting it as a foreign medication. The cost, while higher than that of chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, is significantly less than that of other drugs used to treat connective tissue disorders (in our cases, belimumab and rituximab). The possible adverse effects of treatment with quinacrine include the appearance of a yellowish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes, which resolves when treatment is withdrawn, and the risk of aplastic anemia, which is rare and usually preceded by a lichenoid eruption. Follow-up of patients on quinacrine should include quarterly laboratory testing and annual ophthalmological examinations.7 Hypersensitivity to the active ingredient is the main contraindication for this drug; however, physicians should also bear in mind that quinacrine can exacerbate psychoses, myasthenia gravis, and psoriasis.

Because of the complexity of the management of connective tissue diseases, we consider it opportune to underscore the importance of being aware of this alternative treatment option, which can prove very useful in clinical practice.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García-Montero P, del Boz J, Millán-Cayetano JF, de Troya-Martín M. Quinacrina, un escalón terapéutico que no debemos obviar. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:870–872.