We present the case of a 43-year-old man with a history of mild perinatal anoxic encephalopathy, obesity since childhood, and severe plaque psoriasis diagnosed at 28 years of age, not controlled by topical treatments.

Prior to starting systemic treatment, the patient presented multiple infiltrated and desquamating erythematous plaques, particularly affecting the lumbosacral region and legs, with a psoriasis area severity index (PASI)>15. However, there was no nail or joint involvement. Given the patient's degree of dependence and the lack of response to previous systemic treatments with acitretin and methotrexate, it was decided to start biological therapy, and additional tests were therefore requested, including complete blood count, biochemistry, urinary sediment, chest x-ray, and a tuberculin test, all of which were negative or normal. Treatment was then started with etanercept 50mg administered subcutaneously once a week, after performing the induction course, obtaining a good clinical response and achieving a PASI of 75% at 10 weeks.

Despite normal laboratory results during the anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy and for 2 years of follow-up, a persistent moderate leucopenia was later detected in serial blood tests, and a chest x-ray, serology, and evaluation by the hematology department were therefore requested. A detailed medical history did not detect associated systemic symptoms.

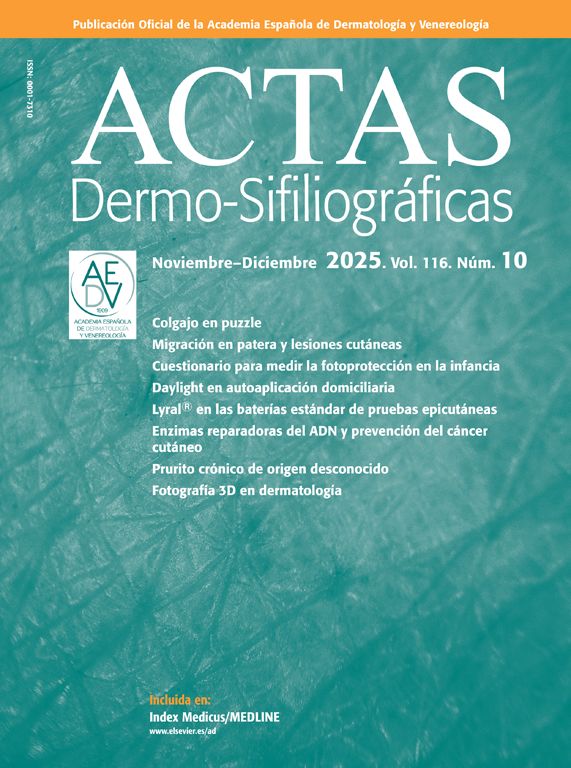

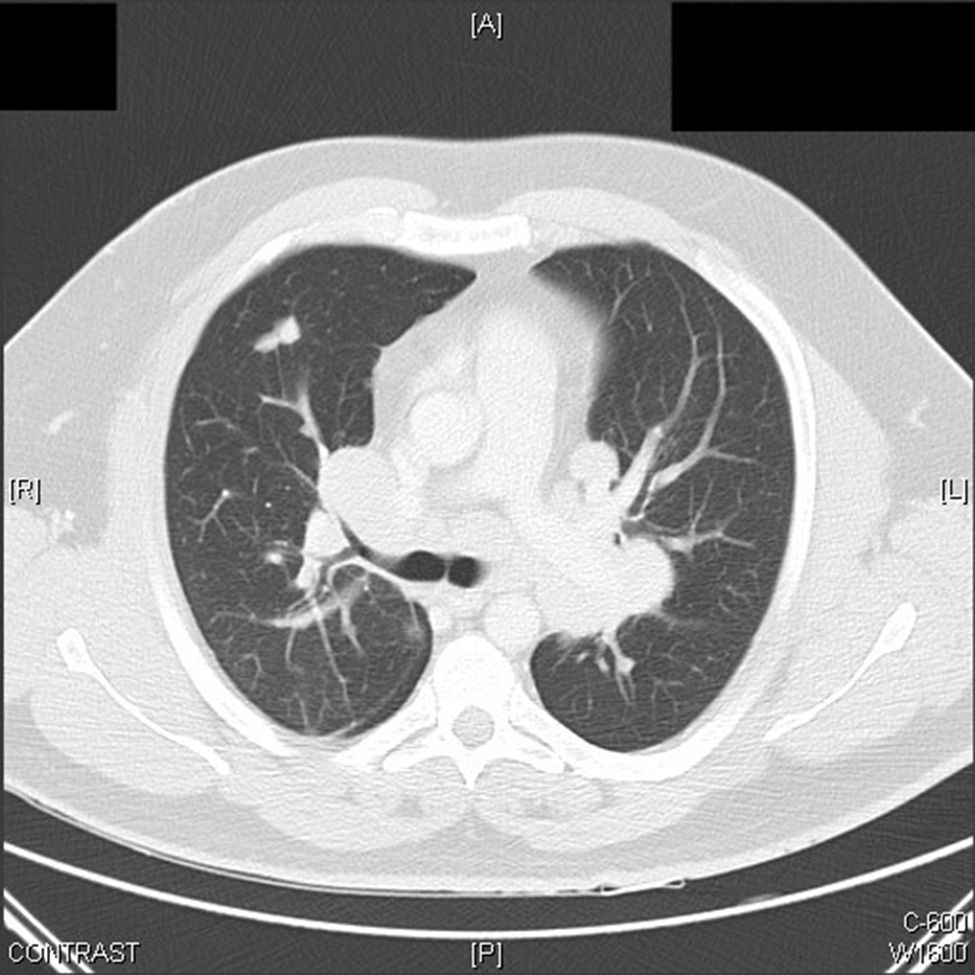

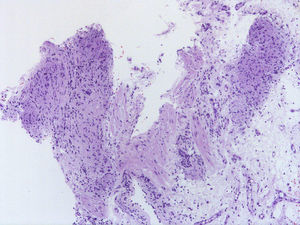

The chest x-ray revealed a parahilar mass consistent with the high-resolution computed tomography findings of multiple mediastinal, parahilar, and supraclavicular lymph nodes and multiple pulmonary nodules (Fig. 1). Given the possibility of a lymphoproliferative disease, mediastinoscopy was performed to take a lymph node biopsy. Histology showed chronic noncaseating granulomatous inflammation with a negative Ziehl-Neelsen stain and negative polymerase chain reaction test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Fig. 2).

Based on these findings, a diagnosis of pulmonary and lymph node sarcoidosis was made and the anti-TNF treatment was interrupted. Given the absence of respiratory symptoms, we took a conservative approach, with clinical and radiological follow-up of the patient.

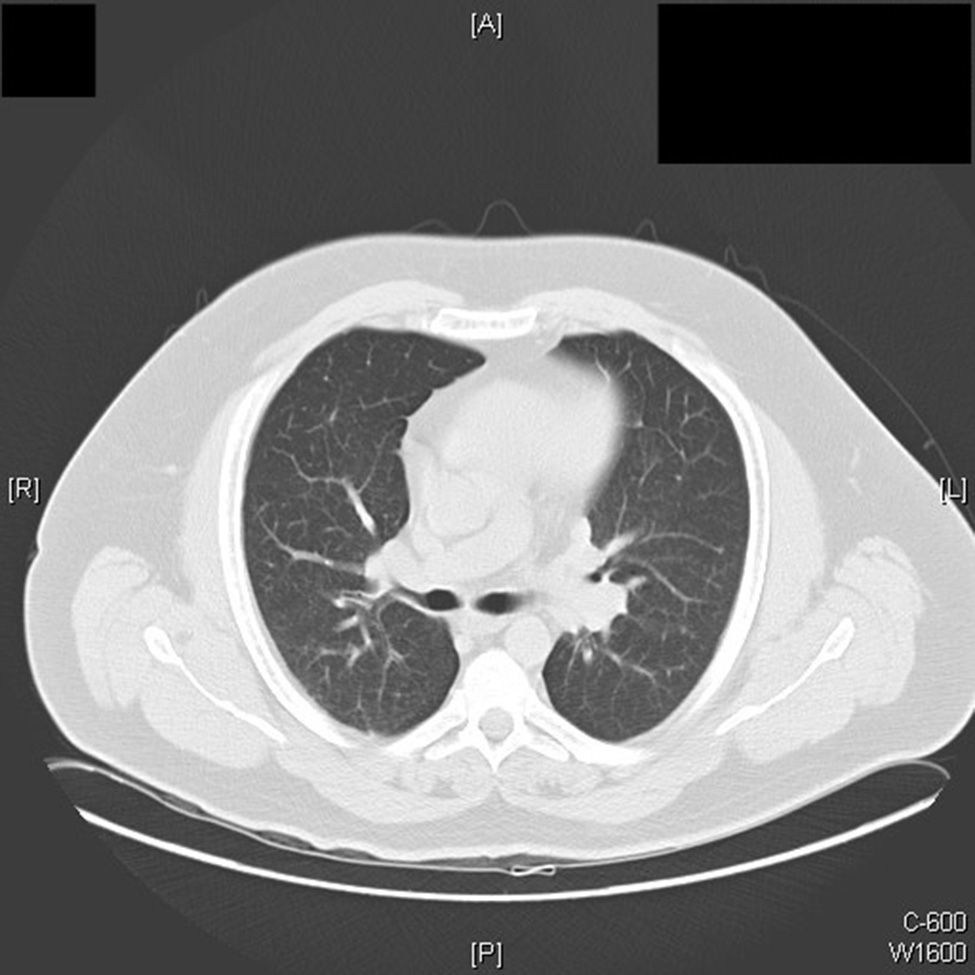

Six months after withdrawing the anti-TNF treatment because of the diagnosis of sarcoidosis, we observed a radiological improvement (Fig. 3) with a marked decrease in the size of the lymphadenopathies, and a complete blood count within normal limits.

The ever wider off-label use of anti-TNF drugs in the fields of rheumatology and dermatology and in autoinflammatory diseases in other specialist fields explains the increase in the incidence of paradoxical phenomena in recent years.1 These are exacerbations or the new appearance of inflammatory conditions that usually respond to the use of anti-TNF therapy,2 such as psoriasiform rashes,3 uveitis, and the onset of other granulomatous diseases (Crohn disease and sarcoidosis). Controversy continues over the etiologic and pathogenic mechanisms underlying these phenomena, although it has been suggested that TNF inhibition may provoke a dysregulation of the compensatory proinflammatory cascade.4

Fewer than 50 cases of pulmonary sarcoidosis induced by anti-TNF treatment have been reported in the literature, and the disease was only confirmed histologically in 27.5,6 The majority of cases have developed in patients with rheumatic inflammatory diseases, particularly rheumatoid arthritis (15%), followed by the spondyloarthropathies (7%) and psoriatic arthritis (4%). The most widely used TNF inhibitor was etanercept (52%), folowed by infliximab (30%) and adalimumab (18%). The diagnosis of sarcoidosis was made after a mean treatment duration of 23 months.7 In all cases the treatment was interrupted and glucocorticoid therapy was administered in half of the patients; the clinical course of the sarcoidosis was satisfactory, with complete resolution in the majority of cases (89%).7

The development of pulmonary sarcoidosis in patients treated with TNF inhibitors for psoriasis without joint involvement is rarer or, at least, it has not been reported as frequently in the literature. Ours is the second reported case induced by etanercept.8

Differences in dosage and the follow-up of patients on TNF inhibitor treatment in rheumatology compared with those with exclusively cutaneous pathology could be the reason for this difference.

Although the etiological and pathogenic mechanisms remain unclear, it has been suggested that TNF inhibition could alter the expression of certain cytokines, such as interleukin (IL) 2, IL-18, and interferon-γ. Although all anti-TNF drugs act by blocking this proinflammatory cytokine, there are major differences both in their structure and in their pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic characteristics. The higher incidence of sarcoidosis with etanercept compared with other anti-TNF agents may be because this drug shows binding limited to transmembrane TNF, leaving the monomeric soluble form unbound, and it does not cause cell lysis, meaning that TNF inhibition would not be sufficient to prevent the formation of granulomas.9

Ever more dermatologic diseases may benefit from the use of anti-TNF agents; the disease that has typically been described is psoriasis,10 but the efficacy of this agent has recently been reported in other inflammatory diseases such as hidradenitis suppurativa and pyoderma gangrenosum. Paradoxical phenomena, in particular sarcoidosis, have been appearing with increasing frequency during treatment with anti-TNF agents, and dermatologists must therefore take this possible complication into account and ensure early recognition.

Please cite this article as: Padilla-España L, Habicheyn-Hiar S, de Troya M. Sarcoidosis pulmonar y ganglionar en un paciente con psoriasis durante terapia anti-TNF alfa: nuevo caso de fenómeno paradójico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:760–762.