Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is a vascular tumor associated with human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8) infection. We describe a case of primary KS of the subcutaneous tissue, a rare clinical manifestation, and review the literature.

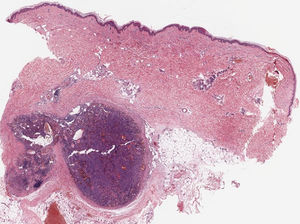

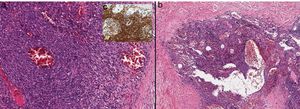

A 78-year-old woman with no remarkable past history presented with nodular lesions of 2 years’ duration on both legs. The lesions were asymptomatic, and while they had not grown, they had increased in number. Physical examination showed multiple nodules measuring less than 2cm covered by normal-appearing skin on both legs and a few nodules on the thighs. The nodules were soft on palpation and not fixed to the deep layers (Fig. 1). There was no associated edema or mucosal involvement. The general blood test results were normal and serology for hepatitis C virus (HCV), HBV, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was negative. Ultrasound showed numerous solid subcutaneous lesions in both legs. The findings were heterogeneous, with a mixture of hyperechogenic and strongly hypoechogenic lesions without detectable flow. Histologic examination showed a well-circumscribed nodule composed of spindle cells with varying degrees of atypia (Fig. 2) in the subcutaneous tissue, in addition to large irregular, dilated vascular channels with a prominent endothelium and abundant hematic content (Fig. 3). Immunohistochemistry was positive for CD31 and HHV-8. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) ruled out lymph node and visceral involvement and confirmed exclusive involvement of the subcutaneous tissue. A diagnosis of primary KS of the subcutaneous tissue was established. Considering the absence of disease spread and severe symptoms, it was decided to adopt a watch-and-wait approach.

A and B, Higher-magnification histologic images showing that the nodule is formed by spindle cells with varying degrees of atypia intermingled with dilated, irregular vascular channels (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×10). C, Spindle cells showing positive staining for human herpes virus 8 (monoclonal antibody, ORF73/HHV-8; original magnification ×20).

KS is a multifocal systemic disease that mainly affects the skin and mucous membranes. Although it is characterized by a proliferation of endothelial cells, it is not yet known whether these cells are derived from lymphatic or blood endothelium.1 KS is etiologically associated with HHV-8 infection combined with factors such as an altered immune system and an inflammatory/angiogenic environment.1 It is classified into 4 clinical/epidemiological groups: classic KS, endemic (African) KS, HIV-associated KS, and immunosuppression-associated KS. HIV-associated KS tends to show a multicentric pattern, with greater mucocutaneous, gastrointestinal, lymph node, visceral, and atypical involvement.

In KS, endothelial transformation typically occurs in the dermis (superficial more often than deep), giving rise to classic lesions, such as macules, papules, and nodules, or violaceous tumors affecting the skin or mucous membranes. Involvement of the subcutaneous tissue and other deep soft tissues and even bone is generally the result of deep extension by superficial lesions.2

Visceral and nodal involvement is uncommon and has been mainly described in immunosuppressed patients, who usually have cutaneous/mucosal lesions. Exclusive extracutaneous KS is rare,1,2 as is primary involvement of the subcutaneous tissue. We found just 6 other cases of patients with subcutaneous nodules without overlying skin involvement in the literature.2–7 All the patients were men and they were all HIV-positive but one. Five of them had a classic KS lesion at another site, facilitating diagnosis. Just 1 patient, a 43-year-old HIV-positive man, had subcutaneous involvement only.2

The mechanism underlying the development of primary KS of the subcutaneous tissue is unknown. Some authors have proposed that chronic lymphedema could have an etiologic role in lymphangiogenesis and immune injury,2,8 but no signs of lymphedema have been detected in the cases described to date. In addition, many patients with classic KS on the legs have edema but do not develop subcutaneous lesions.8 Trauma to the subcutaneous tissue might also have a role in the development of KS, particularly in solitary or very localized lesions. This hypothesis is based on reports of KS arising in scars.

The differential diagnosis for subcutaneous tissue lesions is broad. In immunosuppressed patients, primary KS of the subcutaneous tissue without skin lesions can be difficult to distinguish from other lesions, particularly in patients with infections and other proliferative disorders.

Although skin biopsy is necessary for establishing a definitive diagnosis, imaging studies are essential for guiding diagnosis and determining the extent of disease before treatment initiation. PET-CT is the best tool currently available for assessing subcutaneous disease,9 as lesions show uptake of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose. It is also useful for assessing visceral, nodal, soft tissue, and bone involvement. CT alone is also useful for assessing visceral (mainly lung) involvement, but it is less valuable in soft tissue lesions. T1-weighted (T1W1) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) shows an isointense signal to muscle while T2W2 scanning shows a mainly hyperintense signal that is enhanced with gadolinium. MRI is less sensitive, however, to small lesions in the subcutaneous tissue.9 Scintigraphy has also proven useful for determining the presence and extent of cutaneous and extracutaneous KS associated with HIV infection.3 Skin ultrasound is a useful complementary test, as it provides information on structural and vascular lesions and can also be used to guide biopsy.10

We have presented a new case of primary KS of the subcutaneous tissue and the first-ever case described in an immunocompetent woman. It is important to be familiar with uncommon presentations of KS, such as primary KS of the subcutaneous tissue, to avoid diagnostic and therapeutic delays.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors report no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Franco-Muñoz M, García-Arpa M, Lozano-Masdemont B, Lara-Simón I. Sarcoma de Kaposi subcutáneo primario, una rara variante clínica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:318–320.