Psoriasis is a systemic, chronic inflammatory disease of the skin that present multiple comorbidities, such as psoriatic arthritis and cardiovascular disease, which can even reduce life expectancy, and is accompanied by a considerable physical, mental, and social burden.1 Today's therapeutic arsenal against moderate-to-severe psoriasis is extensive: phototherapy, conventional systemic drugs (ciclosporin, methotrexate, acitretin, fumarates), next-generation synthetic molecules (apremilast and, soon, deucravacitinib), and biological therapies including some biosimilar agents (adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab, ustekinumab, secukinumab, ixekizumab, brodalumab, tildrakizumab, guselkumab, and, soon, bimekizumab). Not all patients respond equally to treatment, however, and access to the most efficacious treatments (biological therapy) tends to be restricted to a small number of patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. Moreover, the high economic cost of the new biological therapies has led nonclinical agents, such as managers and payers, to become major factors in the choice of these treatments.2 A series of requirements have been established for prescribing biological therapy, which, for some patients, involve a delay in receiving their first biological drug. This can mean a lost opportunity to achieve more permanent responses and even prevent progression to more severe forms of the disease, such as joint involvement.3

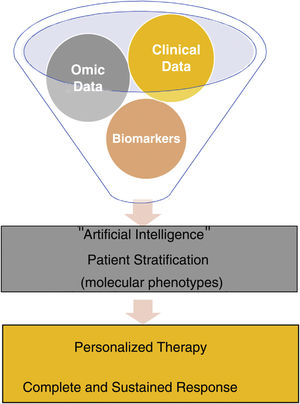

Precision medicine or stratified medicine aims to choose the treatment based on individual patient characteristics, like a tailored suit.4 This strategy has been known for several years in oncology, such as the use of BRAF inhibitors in patients with mutate BRAF melanoma, which have demonstrated an increase in survival in advanced stages, combined with a MEK inhibitor,5 but not so much in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, which are much more heterogeneous and require chronic (sometimes for life) and often expensive treatment. Traditional medicine is based on the use of clinical patterns to diagnose a disease and on trial and error to select treatment. In precision medicine, depending on multiple multi-omic data combined with clinical data obtained and analyzed thanks to current technological advances, patients are classified into different molecular phenotypes (or endotypes) for choosing targeted and personalized therapies, which allow for long-term clearance of the disease in all patients in a cost-effective manner. Precision medicine is based on the idea that subpopulations exist within a disease category and that they can be identified by means of biomarkers, preferably before instating treatment or in the earliest stages6 (Fig. 1).

Advances in knowledge of various aspects of psoriasis and the development of artificial intelligence mean that this individualization can begin to be applied in routine clinical practice. For example, in the field of genetics, the presence of the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-Cw6 allele has been linked to more extensive cutaneous involvement, with early onset of the disease and with a lower risk of developing psoriatic arthritis7; it is also associated with a better response to methotrexate8 and ustekinumab,9 and its absence is associated with a better response to adalimumab.10 With regard to secukinumab, results are contradictory, with some studies that find no link11 and others that do observe an excellent response in patients with HLA-Cw6.12 Little information is available regarding the new IL23 inhibitors and we have found no link between effectiveness and the presence or absence of HLA-Cw6 (personal observation). The finding in forms of pustular psoriasis of mutations in the genes IL36RN, AP1S3, and CARD14 has made it possible to find new therapeutic targets against IL-1 and IL-36 that are in advanced stages of research.13 In relation to treatment, levels of adalimumab and ustekinumab at an early stage may be used to predict and improve results in patients.14,15 Patient phenotype may also be of utility for selecting treatment. In the BIOBADADERM register, women had a higher risk of adverse events but treatment survival was similar to that of men.16 In this Spanish register, we also found that increased body mass index was associated with a higher rate of discontinuation of treatment due to lack of efficacy and higher risk of adverse events.17 Moreover, the effect of the exposome (environment+lifestyle) on the course of the disease and the response to treatment is also interesting, as these are factors that can potentially be modified. A direct relationship exists between smoking and the prevalence and severity of psoriasis,18 and smoking is also associated with decreased efficacy of biologic therapies.19 Alcohol consumption is also more frequent in patients with psoriasis, and it may also trigger episodes of the disease.20

Having biomarkers, which will probably arise from a combination of demographic, phenotypic, genomic, and biochemical data, will help us to better understand the natural history of psoriasis, the factors that can predict its appearance and episodes, the development of comorbidities, and the response to therapy of each individual. Today, we have the opportunity to use the data from registers, and the use of digital health will make it possible to collect data remotely and/or continuously, which, together with advances in artificial intelligence, will allow us to develop algorithms to focus management of patients with psoriasis in an individualized manner, as recommended by the World Health Organization in 2016 in its global report dedicated to this diseases.21 It is important to choose the right drug for the right patient at the right time.

Conflicts of InterestDr. Rivera-Díaz has taken part as advisor/author/researcher in clinical trials promoted by companies that produce drugs for the treatment of psoriasis, including Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Almirall SA, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Lilly, AbbVie, Novartis, Celgene, Biogen Amgen, Leo-Pharma, and UCB.

Dr. Belinchón has taken part as advisor/author/researcher in clinical trials promoted by companies that produce drugs for the treatment of psoriasis, including Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Almirall SA, Lilly, AbbVie, Novartis, Celgene, Biogen Amgen, Leo-Pharma, Pfizer-Wyeth, MSD, and UCB.