Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta and pityriasis lichenoides chronica represent 2 ends of a disease spectrum of unknown etiology. Herein we describe 2 cases of pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta, in which human herpesvirus 7 DNA was detected in skin samples by polymerase chain reaction methodology, an association not previously described. This report may support the involvement of viral infection in the etiopathogeny of this disease.

Tanto la pitiriasis liquenoide y varioliforme aguda como la pitiriasis liquenoide crónica representan 2 extremos de un espectro de enfermedad de etiología desconocida. En este trabajo se describen 2 casos de pitiriasis liquenoide y varioliforme aguda, en los que se detectó ADN de virus herpes humano tipo 7 en muestras de piel mediante la metodología de reacción en cadena de la polimerasa, una asociación no descrita previamente. Este manuscrito puede apoyar la participación de la infección viral en la etiopatogenia de esta enfermedad.

Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) and pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) represent two ends of a disease spectrum in which both entities and intermediate forms may coexist.1 Clinical presentations ranges from an acute eruption of inflammatory papules and papulovesicles that develop hemorrhagic necrosis lasting for weeks in PLEVA to scaling brownish papules that persist for months in PLC.2 The diagnosis relies on clinical presentation and lesions histopathology.3 The physiopathology is not totally understood although some cases have been linked to infectious agents.4,5

Herein we describe two cases of PLEVA associated with human herpesvirus 7 (HHV-7).

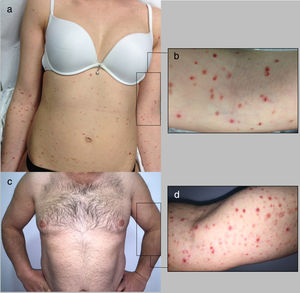

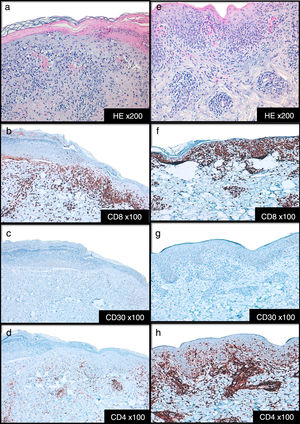

Cases DescriptionCase 1: A 26 year-old previously healthy woman was addressed to our department due to a generalized pruritic eruption with 2 weeks evolution. No other signs, symptoms or drug intake were mentioned. The physical examination revealed multiple erythematous papules widespread on limbs and trunk, some with hemorrhagic crusts and others with fine scale (Figure 1a-b). No palpable adenopathies were detected. The laboratory workup found a slightly elevated C-reactive protein (13mg/l; normal<3) with normal blood cell counts, liver and renal chemistries and negative antinuclear antibodies. Serology for hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and syphilis were negative. Serology for cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1, parvovirus B19 and varicella zoster virus (VZV) were positive for IgG antibodies but negative for IgM antibodies suggesting a past infection. Serology for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and HSV 2 were negative for both IgM and IgG antibodies. Skin biopsy revealed epidermal acanthosis, orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and a dermal perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate associated with extravasated erythrocytes (Figure 2a). Immunohistochemistry showed a predominance of CD8+ T cells, decreased Langerhans cells and no evidence of CD30+ cells. (Figure 2b-d). Real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test detected HHV-7 DNA and was negative for human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) and Treponema pallidum DNA in the skin fragment. The diagnosis of PLEVA was made on clinical and histopathological grounds. Oral clarithromycin (500mg PO twice daily) and topical betamethasone valerate associated to fusidic acid were prescribed, with complete remission of lesions after 1 month. No recurrence was registered at 4 months follow-up.

Case 2: A 44-year-old man was referred to our clinic for generalized asymptomatic eruption of 6 weeks duration, consisting of erythematous, scaly and crusted papules and small plaques on the trunk and extremities (Figure 1c-d). He denied any associated systemic symptoms. His medical record was unremarkable and there was no history of precipitating factors, including drug intake or infection before the onset of rash. No palpable adenopathies were detected. Laboratory analysis, including full blood cell count with differential, liver and renal chemistries and antinuclear antibodies were within normal ranges. Serology for HBV, HCV, HIV and syphilis screen were negative. Histopathological examination revealed epidermal hyperkeratosis, an extensive dermal and epidermal lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, associated with vacuolization of basal layer and extravasated erythrocytes in papilar dermis (Figure 2e). Immunohistochemistry showed a predominance of intra-epidermal CD8+ T cells with perivascular CD4+ T cells, and decreased/absence of Langerhans cells and CD30+ cells (Figure 2f-h). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of PLEVA. The RT-PCR test was positive for HHV-7 DNA and negative for HHV-6 and Treponema pallidum DNA in the skin fragment. Qualitative RT-PCR test was negative for plasma HHV-6 and HHV-7 DNA. Oral doxycycline (100mg twice daily) and topical betamethasone valerate associated to fusidic acid were prescribed. After one week the patient noticed improvement and stopped the treatment spontaneously. No recurrence of lesions was registered at 2 months follow-up.

DiscussionThe pathogenesis of pityriasis lichenoides (PL) is unclear and several hypotheses have been proposed.4 PL could be an inflammatory reaction triggered by extrinsic antigens and multiple agents have been implicated. Infectious agents as virus (HIV, CMV, EBV, parvovirus B19, VZV, adenovirus, HCV, human herpesvirus 8, and HSV),5–7 bacteria (beta hemolytic Steptococcus and coagulase positive Staphylococcus)5 or protozoa (Toxoplasma gondii)5 have been pointed as PLEVA triggers. Drugs (hormone therapy with estrogen-progesterone, antibiotics, acetaminophen, immunoglobulins, biologics, cytostatics, and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors)3,8–10 and vaccines (live-attenuated measles vaccine, the combined measles-mumps-rubella vaccine, tetanus vaccination, hepatitis B vaccine) have also been associated to PLEVA.3,5 In accordance with this theory, the detection of T cell clones in PL could represent a clonal immunologic response to a extrinsic antigen. However, one study found a history of infection in only 30% patients with PL.11 Infrequent reports of PL evolving into cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and detection of T-cell clonality have led some to hypothesize that PL, though not a true cutaneous T cell lymphoma, represent an inflammatory reaction to an underlying T cell dyscrasia.12 Nevertheless, monoclonality is not uniformly detected in PL and detection of monoclonality is not sufficient to designate a disorder as a primary lymphoproliferative disease.12 Finally, some authors demonstrated the presence of a component of immunocomplex-mediated vasculitis in PL.3

Many cases of PL have an autoinvolutive trend and need no therapy. In more severe cases therapy is indicated and includes systemic antibiotics, topical anti-inflammatory drugs, systemic immunosuppressive drugs and ultraviolet phototherapy.5 The reason these treatments work remains a mystery.

In our PLEVA patients, HHV-7 DNA was detected in skin samples by qualitative RT-PCR method, an association not previously described. Similar to other human herpes viruses, infections with HHV-7 can manifest with cutaneous involvement.13 HHV-7 had been implicated in the ethiopatogeny of inflammatory skin disorders as pityriasis rosea and lichen planus.13,14 There is also some evidence on the role of HHV-7 in exanthema subitum (roseola infantum) and other childhood rashes.13,14 In addition, drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome has been associated with reactivation of HHV-7, either alone or together with HHV-6.14 The role of HHV-7 in various systemic diseases, as well as in skin disorders, has still to be defined.

Despite the similarities of our patients, including clinical picture, histopathology, HHV-7 positivity and evolution, proving a viral etiology is a complex problem. Qualitative molecular methods, such as RT-PCR, are highly sensitive but do not provide conclusive evidence for an etiologic link.15 PCR can only assess the mere presence of HHV DNA. It cannot evaluate the relative importance of the viral DNA contamination from latently infected cell and HHV-7 is a lymphotropic virus that replicates in CD4+ T-lymphocytes.15 The high prevalence of HHV-7 infection in the general population is an additional difficulty.15 HHV-7 can be induced from latency within T cells by cell activation. This may explain the detection of the virus in the skin fragment. Interestingly HHV6, which replicates most efficiently in activated primary T cells was not detected in our patients.

The ability of HHV-7 to induce cytokine production in infected cells could make HHV-7 an important pathogenic co-factor in inflammatory and neoplastic disorders.13 The presence of HHV-7 in the lesional skin of patients may indicate a role for this virus in the pathogenesis of PLEVA. However, it is unclear if HHV-7 acts as an authentic antigenic trigger of PLEVA or represents a coincident association.

ConclusionThis report allows to infer the possibility of HHV-7 playing a role in the pathogenesis of PLEVA which may support the involvement of viral infection in this disease. Additional studies are needed to determine the precise role of HHV-7 or other infectious agents in the etiopathogeny of PLEVA.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Costa-Silva M, Calistru A, Sobrinho-Simões J, Lisboa C, Azevedo F. Pitiriasis liquenoide y varioliforme aguda asociada al virus herpes humano tipo 7. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:e6–e10.