Pemphigoid gestationis or herpes gestationis is a subepidermal blistering disease that occurs in women in the second or third trimesters of pregnancy or even during puerperium. It is a rare skin disease whose incidence has been estimated at around 1 case in every 40 000 to 60 000 pregnancies. It is more common in patients with HLA DR3 and DR4 haplotypes.1 Although most cases respond well to oral corticosteroids, some can be resistant to this and other treatments. We report a case in which we successfully applied intravenous immunoglobulin treatment.

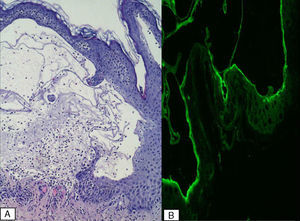

A 25-year-old, primiparous woman with hypertension on treatment with enalapril, presented in the second trimester of pregnancy, at 22 weeks, with a rash of intensely pruritic plaques that started in the periumbilical region and subsequently appeared on the anterior aspect of both wrists and extensor surfaces of the lower limbs. Laboratory and serological tests (hepatitis B and C viruses, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus) showed no abnormalities except for mild eosinophilia. Tense blisters developed on several of the lesions (Fig. 1A). Histology revealed edema with an infiltrate formed of lymphocytes and abundant eosinophils (Fig. 2A), and direct immunofluorescence showed linear deposits of C3 at the dermoepidermal junction (Fig. 2B). Pemphigoid gestationis was diagnosed and treatment was initiated with prednisone (30mg/d). The dose was increased to 60mg/day and subsequently to 75mg/d due to the lack of response on weekly follow-up.

In the final month of pregnancy intravenous immunoglobulin was administered at a dose of 500 mg/kg/d for 5 days. We succeeded in reducing the dose of prednisone to 30mg/kg/d (reducing 5mg/wk until that dose was reached) with no worsening of symptoms.

At 15 days after delivery, the dose of prednisone was dropped to 15mg/d. In agreement with the gynecology department of our hospital, a new course of intravenous immunoglobulin was initiated at the same dose in order to prevent a probable resurgence of the condition, given the poor response. At 18 weeks after delivery, prednisone was suspended with no recurrence of lesions in the following 6 months (Fig. 1B). Follow-up laboratory tests and blood pressure values showed no variation either during or after treatment.

The treatment of choice in pemphigoid gestationis is oral corticosteroids. The usual dose is around 0.5mg/kg/d of prednisone by mouth, which rapidly improves symptoms in most cases. However, systemic corticosteroid therapy is sometimes insufficient to control the disorder, as occurred in our patient. Other treatments have been tested, including plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, pyridoxine, ritodrine, and immunosuppressant drugs such as cyclosporin,2 azathioprine, dapsone, and tacrolimus.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune bullous diseases resistant to conventional treatment is increasing, since it offers a convenient alternative treatment with few side effects, most of which are mild and self-limiting. Episodes of flushing, myalgia, headaches, nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, and a slight increase in blood pressure have been reported in most cases between 30 and 60minutes after starting infusion.3 Anaphylaxis is very rare and has mainly occurred in patients with immunoglobulin A deficiency. These adverse effects are almost always avoidable with premedication according to an established protocol at the medical day care units where the infusion is administered.4

The literature reports few cases of the use of intravenous immunoglobulin in pemphigoid gestationis,5–8 though it has been employed successfully to manage other blistering diseases such as pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, and acquired epidermolysis bullosa.8 The mechanism of action of intravenous immunoglobulin is not fully understood but it appears to act at different points in the immune cascade, including functional blockade of Fc receptors on splenic macrophages, inhibition of complement-mediated actions, and modulation of cytokine production.3

In the absence of large patient series, given the low incidence of this pathology, the dose and time of administration of immunoglobulin vary according to the author reviewed. No significant differences were detected between regimens of 3 or 5 days, and most authors followed existing protocols at their hospitals. We considered applying this treatment pre- and postpartum in order to control skin disease in the final stages of pregnancy and prevent a possible recurrence during the puerperium.Jolles et al3 observed that treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin in autoimmune bullous diseases is always more successful when used as adjuvant therapy (91%) rather than monotherapy (51%). Subsequently published cases of pemphigoid gestationis report therapeutic success in both situations.5–8

In our patient, we used intravenous immunoglobulin associated with systemic corticosteroids, owing to the difficulty of controlling the skin symptoms and taking into account that corticosteroids during pregnancy can involve risk for the fetus (growth retardation, prematurity) and for the mother (osteonecrosis, hypertension, infections, etc.). We believe that the regimen followed in our patient may be of interest in cases with an indolent clinical course and that are refractory to conventional treatment.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Villaverde R, et al. Penfigoide gestacional. Respuesta terapéutica a inmunoglobulinas pre y postparto. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:735-747.