Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) and Behçet's disease (BD) are part of the Behçet spectrum disorders (BSD), sharing genetic traits and characterized by recurrent ulcers. No systemic treatment is approved for RAS or incomplete BD, despite significant quality-of-life impacts.

ObjectiveTo evaluate the efficacy of roflumilast, a PDE4 inhibitor, in BSD patients and compare responses between RAS and BD.

MethodsThis analytical observational study included a total of 33 patients with BSD (22, RAS; 11, BD) from 5 Spanish centers, followed over 52 weeks. Data were collected retrospectively and prospectively, assessing flare-ups, ulcers, pain, and duration. Statistical models compared outcomes across treatment periods.

ResultsRoflumilast significantly reduced all studied response variables, with no loss of long-term efficacy. Differences between RAS and BD were minimal and clinically irrelevant. Adverse events occurred in 63% of patients, mostly mild and self-limiting, with tolerability improved through dose adjustments. Two patients (6.25%) dropped out due to adverse events.

ConclusionRoflumilast is effective for managing BSD, offering a safe option to address unmet needs in RAS and BD. Its favorable safety profile and long-term efficacy support its use in the routine clinical practice.

Oral ulceration affects up to 25% of the population and a higher percentage of young patients.1 Recurrent aphthous stomatitis (RAS) is characterized by recurrent painful oral ulcers not attributable to local trauma, infection or systemic disease. It affects between 5% and 25% of the population.2 Behçet's disease (BD) is a relapsing multisystemic vasculitis, including oral ulcers, genital ulcers and/or different systemic signs.3 Although, historically, RAS and BD have been considered independent conditions, recent studies have identified genetic similarities between RAS and BD, suggesting a spectrum of disease that has been named “Behçet spectrum disorders” (BSD).1,4 In this spectrum, RAS is the mildest sign and BD the most severe one.

Treatment of RAS and the mucocutaneous phenotype of BD aims to improve the patients’ quality of life by suppressing inflammation and preventing relapses.5,6 However, there is no approved systemic treatment for RAS and incomplete BD, despite its significant impact on quality of life. Therefore, there is an unmet need for a wider range of therapeutic options.1 First-line therapies generally include topical therapies, while second-line options often include immunosuppressants or systemic immunomodulators that require close monitoring or may have significant adverse effects (AEs).1,5,6

It has been suggested that the overlap in genetic susceptibility loci between BSD conditions could be extrapolated to treatment strategies.4 Demonstrating this genetic-therapeutic correlation could allow different clinical presentations of the spectrum (such as incomplete BD, which do not fit into any of the conditions) to benefit from former studies and/or approved treatments in other conditions of the spectrum. However, to our knowledge, no study has ever been conducted where the efficacy of a treatment in different conditions of the spectrum has been analyzed simultaneously.

We have studied the efficacy of roflumilast, a PDE4 inhibitor (PDE4i), in patients with RAS and BD at 12 weeks, which is notable for its efficacy and favorable safety profile.7,8

This study aims to describe and analyze the efficacy of roflumilast in the long-term treatment of BSD and to assess, using the same methodology, whether there are differences in effectiveness between pathologies considered to be at the extremes of the spectrum.

MethodsStudy designWe conducted this analytical observational 2-cohort study with ambispective follow-up with participation of 5 Spanish centers. Patient data were collected from health records and/or direct anamnesis, both retrospectively and prospectively. Demographic, clinical and outcome variables were collected. Outcome variables included the number of flare-ups (NFU), defined as the occurrence of at least 1 ulcer after a period of remission, the number of oral ulcers (NOU), the number of genital ulcers (NGU), the pain produced by ulcers assessed with the numeric pain scale (pain-NRS) and the duration of ulcers in days (DU). NFU was recorded between 0 and 4. Patients with continuous ulcers without periods of remission were categorized as grade 4. NOU, NGU, DU (in days), and pain NRS (0–10) were recorded as discrete numerical variables.

The response variables NFU, NOU and NGU were compared in 5 time periods: the last 3 months without treatment (WT), the first 3 months of roflumilast treatment (RT3), months 4–6 (RT6), months 7–9 (RT9) and months 10–12 of treatment (RT12). The variables DU and pain-NRS were compared between the WT period and 52 weeks of roflumilast treatment (RT).

Other data collected included the presence of other signs associated with Behçet's disease, the roflumilast dose used at each moment and the presence of AEs and their progression over time. If the drug was withdrawn prior to 52 weeks, the cause was detailed.

Demographic, clinical and outcome variables were collected retrospectively during the WT period and while on roflumilast until study approval by the medical research ethics committee of the principal investigator's center. Subsequently, data were collected prospectively.

This study was approved by the medical research ethics committee of the principal investigator's center.

Study populationInclusion criteria- -

Patients diagnosed with BD based on the ICBD 2013 criteria.9

- -

Patients diagnosed with RAS who presented quality of life impairment that justified the use of systemic treatment.

- -

Patients with BD or RAS who have started treatment with roflumilast prior to the inclusion of their center in the study.

- •

Patients with oral or genital ulcers due to other conditions, such as infectious ulcers, anemia, traumatic ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren's syndrome, and drug-related tumors or ulcers.

The primary endpoint was to evaluate the reduction in the NFU during treatment with roflumilast vs the untreated period. Secondary endpoints included assessing reductions in NOU, NGU, pain-NRS and DU during roflumilast treatment. Additional endpoints were to determine whether treatment effectiveness varied over time or by the specific BSD disease and assess the safety profile of the treatment.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistics software version 26.0 and OpenEpi epidemiological calculator. Values were considered statistically significant if p<0.05. Bonferroni corrections have been applied in the multiple comparisons analyses.

Statistical analysis of NFU, NOU and NGU variables has been performed using a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a Poisson distribution and log link. Follow-up time was added as an offset variable to model rates instead of counts. Repeated measures linear mixed models (LMM) with normal distribution and identity link were applied in the analysis of the pain-NRS and DU variables. Pathology was included in the models to evaluate its role as a differentiating factor in treatment efficacy.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the potential impact of loss to follow-up (treatment withdrawals) on the estimated effectiveness of roflumilast. The main scenario was obtained by imputing loss to follow-up using GLMM and LMM (intention-to-treat approach). Alternative scenarios included carrying forward the last observed data of patients who withdrew (intention-to-treat), analysis of complete cases and a scenario in which all losses were assumed to show a subsequent worsening of response variables (worst-case scenario). To handle violations of normality and low sample size assumptions, Kenward–Roger Restricted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (REML) methods10 were applied.

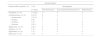

Results up to 52 weeksPatientsA total of 33 patients with BSD were studied, 11 diagnosed with BD and 22 with RAS. The clinical and demographic features and therapies received are shown in Table 1. While on roflumilast, 0 patient received concomitant therapy. Clinical controls were performed, on average, every 30.6 days.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients.

| Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | RAS | BD | BSD |

| n=22 | n=11 | n=33 | |

| Female sex – no. (%) | 12 (54.5%) | 6 (54.5%) | 18 (53.5) |

| Age – yr | 44.7±15.1 {44.5} | 33.8±8.81 {35} | 41.1±14.2 {39} |

| • Female | 43.6±18.1 {45.5} | 32.5±5.5 {32} | 39.9±15.8 {37.5] |

| • Male | 46±11.2 {44} | 33.8±12.3 {39} | 42.5±12.3 {42} |

| Family history of aphthous ulcers – no (%) | 3 (13.6) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (18.1) |

| Other BD signs – no (%) | 1 (4.5) | 9 (81.8) | 10 (30.3) |

| • Erythema nodosum | 1 (4.5) | 6 (54.5) | 7 (21.2) |

| • Acneiform lesions | – | 8 (72.7) | 8 (24.2) |

| Course of the disease – yr | 17.1±15.4 {10} | 14.4±11.9 {8} | 16.2±14.2 {10} |

| • Female | 18.1±16.3 {10} | 13.3±9.9 {11} | 16.5±14.3 {10} |

| • Male | 15.9±15.2 {12} | 15.6±15.2 {8} | 15.8±14.6 {8} |

| ANA – no. (%) | 5 (23.8) | 1 (9.1) | 6 (18.1) |

| HLA-B51– n (tested) | 19 | 11 | 30 |

| • No. (%) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (18.1) |

| Other HLA-B – no. (%)c | 17 | 9 | 26 |

| • B05 | – | 1 (11.1) | 1 (3.8) |

| • B07 | 2 (11.8) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (11.5) |

| • B08 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| • B13 | 1a (5.9) | – | 1a (3.8) |

| • B14 | 3a (17.6) | – | 3a (11.5) |

| • B15 | 1 (5.9) | – | 1 (3.8) |

| • B18 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| • B27 | 2 (11.8) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (11.5) |

| • B35 | 3a (17.6) | 1a (11.1) | 4b (15.4) |

| • B38 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| • B39 | 1 (5.9) | – | 1 (3.8) |

| • B40 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| • B44 | 5 (29.4) | 2 (22.2) | 7 (26.9) |

| • B45 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| • B49 | 2 (11.8) | – | 2 (7.7) |

| • B50 | – | 1 (11.1) | 1 (3.8) |

| • B53 | 1 (5.9) | – | 1 (3.8) |

| • B56 | – | 1 (11.1) | 1 (3.8) |

| • B57 | 1 (5.9) | 1 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) |

| • B58 | 1 (5.9) | – | 1 (3.8) |

| Initial treatment – no. (%) | 20 (90.9) | 11 (100) | 31 (93.9) |

| • Topical glucocorticoid | 14 (63.6) | 4 (36.4) | 18 (56.3) |

| • Colchicine | 5 (22.7) | 6 (54.5) | 11 (34.4) |

| • Glucocorticoid | 1 (4.5) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (6.3) |

| Total previous drugs – no. (%)d | 20 (90.9) | 11 (100) | 31 (93.9) |

| • Topical glucocorticoid | 15 (68.2) | 6 (64.5) | 21 (67.7) |

| • Colchicine | 9 (40.9) | 8 (72.7) | 17 (54.8) |

| • Glucocorticoid | 4 (18.2) | 4 (36.4) | 8 (25.8) |

| • Ciclosporine | 2 (9.1) | – | 2 (6.5) |

| • Dapsone | 2 (9.1) | 2 (18.2) | 4 (12.9) |

| • Sulfasalazine | 2 (9.1) | – | 2 (6.5) |

| • Apremilast | 1 (4.5) | 5 (45.5) | 6 (19.4) |

| • Azatioprine | 1 (4.5) | – | 1 (3.2) |

| • Doxycycline | 1 (4.5) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (6.1) |

| • Hydroxychloroquine | 1 (4.5) | – | 1 (3.2) |

| • Adalimumab | – | 1 (9.1) | 1 (3.2) |

ANA: antinuclear antibodies; BD: Behçet's disease; BSD: Behçet spectrum disorders; HLA: human leucocyte antigen; RAS: recurrent aphthous stomatitis.

Roflumilast was started in 20 patients at 250μg/day, in 9 patients at 125μg/day for 7 days and 250μg/day thereafter, in 2 patients at 500μg/day, and in 2 patients at 125μg/day with no subsequent increase.

Maintenance dose was 500μg/day in 9 patients, 250μg/day in 18 patients and 125μg/day in 3. In the BD group, 6 patients (54.5%) remained on 500μg/day, 4 (36.4%) on 250μg/day and 1 (9%) on 125μg/day. In the RAS group, 3 patients (15.8%) remained on 500μg/day, 14 (73.7%) on 250μg/day, and 2 (10.5%) on 125μg/day.

EfficacyThe analysis revealed a statistically significant reduction in all response variables (NFU, NOU, NGU, DU, and pain-NRS) during the treatment period (RT3, RT6, RT9 and RT12 or RT) vs the untreated period (WT) (Fig. 1 and Table 2).

Incidence density of number of flare-ups (NFU), number of oral ulcers (NOU) and number of genital ulcers (NGU) according to each treatment period. Mean pain-NRS and duration of ulcers (DU) comparing the untreated period with the 52-week regimen of roflumilast. BD: Behçet disease; RAS: recurrent aphthous stomatitis; RT: roflumilast treatment: RT3 (0–3 months); RT6 (3–6 months); RT9 (6–9 months); RT12 (9–12 months).

Primary and secondary efficacy end points at week 52.*

| WT(3 months) | RT3(0–3 months) | RT6(4–6 months) | RT9(7–9 months) | RT12(10–12 months) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=33) | (n=33) | (n=30) | (n=29) | (n=26) | |||||

| Incidence density(100 person-days) | Rate ratio(RR) | Exposed attributable fraction | Rate ratio(RR) | Exposed attributable fraction | Rate ratio(RR) | Exposed attributable fraction | Rate ratio(RR) | Exposed attributable fraction | |

| No. flare-upsa- p-Value | 11– | 0.116 [0.076, 0.175]0.000 | −88.4 [−92.4, −82.5]0.000 | 0.163 [0.114, 0.234]0.000 | −83.7 [88.6, 76.6]0.000 | 0.141 [0.097, 0.204]0.000 | −85.9 [−90.3, −79.6]0.000 | 0.154 [0.107, 0.223]0.000 | −84.6 [−89.3, −77.7]0.000 |

| No. of oral ulcersa- p-Value | 42.4– | 0.054 [0.03, 0.097]0.000 | −94.6 [−97, −90.3]0.000 | 0.079 [0.048, 0.13]0.000 | −92.1 [−95.2, −87]0.000 | 0.053 [0.029, 0.096]0.000 | −94.7 [−97.1, −90.4]0.000 | 0.081 [0.05, 0.132]0.000 | −91.9 [−95, −86.8]0.000 |

| No. of genital ulcersa- p-Value | 4.8– | 0.014 [0, 0.506]0.000 | −98.6 [−100, −49.4]0.000 | 0.042 [0.011, 0.16]0.000 | −95.8 [−98.9, −84]0.000 | 0.02 [0.003, 0.121]0.000 | −98 [−99.7, −87.9]0.000 | 0.013 [0.001, 0.115]0.000 | −98.7 [88.5, 99.9]0.000 |

| WT(3 months) | RT(0–12 months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Mean | Mean difference | |

| Pain-NRSb- p-Value | 7.86 [7.13, 8.6] | 3.86 [3.1, 4.63]<0.001 | 4.0<0.001 |

| Duration of ulcersb- p-Value | 12.39 [10.9, 13.85] | 5.844 [4.26, 7.43]<0.001 | 6.546<0.001 |

.

RT: roflumilast treatment period: RT3 (0–3 months); RT6 (3–6 months); RT9 (6–9 months); RT12 (9–12 months); WT: without treatment period.

In most scenarios, no significant differences were observed between treatment periods, indicating no loss or gain in efficacy over time. Disease-specific analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in NOU and DU. However, during the RT6 and RT9 periods, patients with BD exhibited a significantly higher incidence rate of flare-ups vs those with RAS, whereas no differences were observed during the RT3 and RT12 periods. In the pain-NRS variable, significant differences were found between conditions, with a higher reduction in pain in RAS vs BD (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Detailed results from the scenario analyses are provided in the supplementary data.

Among the 25 patients who completed the 52-week regimen, satisfaction ratings (NRS 0–10) were collected for 23 patients. The mean satisfaction score was 9.41, with a median and mode of 10.

While on roflumilast, 5 patients with BD (45.4%) had episodes of erythema nodosum and 4 (36%), acneiform lesions. Three of the patients with erythema nodosum had severe flare-ups that required discontinuation of roflumilast and switched to a different therapy. Another patient still exhibited lesions with the same frequency, yet reported less symptomatology.

SafetyA total of 21 patients (63%) had AEs. Headache was the most common AE, present in 11 patients. GI disturbances were reported by 9 patients, including abdominal discomfort, nausea-vomiting and diarrhea. Three patients had weight loss, ranging from 3 to 8kg. All 3 cases described weight loss between 3 and 8 months, with subsequent stabilization reported. Asthenia, back pain and nightmares were described in 1 patient in each case. Most AEs were self-limiting or controllable with dose reduction or dose splitting. Two patients withdrew drugs due to AEs, both before the first month of treatment (Table 3).

Summarizing adverse effects and course/management of the disease.

| Adverse effects* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse effects (yes)No. (%) | n (%) | Management | ||

| 21 (63.6) | Self-resolution(n) | Dose reduction/fractionationa(n) | Withdrawal(n) | |

| Headache, no. (%) | 11 (33.3) | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| GI disturbances, no. (%) | 9 (27.3) | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| • GI discomfort | 7 (21.2) | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| • Nausea | 2 (6) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| • Vomiting | 1 (3) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| • Diarrhea | 3 (9.1) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Weight loss, no. (%) | 3 (9.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asthenia, no. (%) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Nightmares, no. (%) | 1 (3) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Back pain, no. (%) | 1 (3) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Two of the 9 patients on 500μg/day experienced AEs characterized by GI discomfort, which resolved when the daily dose was split into 2 doses of 250μg (250μg bid). Three of the 18 patients on 250μg/day experienced persistent AEs at this dose that resolved when the dose was divided into 2 doses of 125μg (125μg bid).

Twenty-five of the 33 patients completed the 52-week regimen, and 8 discontinued it (Table 4). Five patients with RAS and 3 with BD discontinued treatment. Three of these within the first month: 1 due to perceived inefficacy after a single flare-up of 2 ulcers and 2 due to AEs. Three months into therapy, a total of 5 withdrawals were reported. In 3 patients with BD, roflumilast was withdrawn due to severe erythema nodosum and fever, despite partial control of oral/genital ulcers. These patients were switched to adalimumab, achieving complete response. One patient with RAS, who was in complete control, withdrew after 6 months due to genic desire; flare-ups recurred 14 days later. Another RAS patient withdrew after 7 months, unwilling to continue long-term treatment. This patient, in partial response during treatment, experienced worsened flare-ups within 8 days. Follow-up was interrupted but resumed 4 months later. At this point the patient had restarted roflumilast on his own, reporting partial control and a quality-of-life score of 8.5/10. Despite resumption, this case was recorded as a withdrawal.

Summary of reasons for treatment withdrawal and dose at the time of withdrawal.

| Treatment withdrawals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Withdrawal (yes), no. (%) | n (%) | Dose at time of treatment withdrawal | ||

| 8 (24.2) | 125μg/24h | 250μg/24h | 500μg/24h | |

| Adverse events, no. (%)* | 2 (6) | |||

| • Asthenia | 1 (3) | – | 1 | – |

| • GI discomforta | 1 (3) | – | – | 1 |

| Lack of effectiveness, no. (%) | 4 (12.1) | – | – | – |

| • Erythema nodosum and fever | 3 (9.1) | – | 2 | 1 |

| • Self-perceivedb | 1 (3) | – | 1 | – |

| Genesic desire, no. (%) | 1 (3) | – | – | 1 |

| Own-account withdrawal, no. (%)c | 1 (3) | – | 1 | – |

RAS and BD are two conditions characterized by the appearance of oral ulcers, which in BD may be associated with genital ulcers or other cutaneous and/or systemic signs.2,3 Recent studies have identified shared genetic susceptibility loci for both conditions,1,4 suggesting they may belong to a disease spectrum termed BSD.4 It has been hypothesized that this overlap could be extrapolated to therapeutic options.4 To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy profile of treatment in BSD. Demonstrating similar therapeutic efficacy for both conditions would support the spectrum hypothesis and expand treatment options for patients with BSD. Currently, the only approved treatment for BD-associated aphthosis is apremilast, a PDE4i,11 and there is no approved treatment for RAS or for patients with oral or genital ulcers and other BD manifestations who do not meet diagnostic criteria.

This study showed statistically and clinically significant improvements across all parameters during roflumilast treatment. Roflumilast appears effective for BSD overall, as well as in the BD and RAS subgroups.

No significant differences in treatment response were observed between the two conditions, except for the NFU (at RT6 and RT9) and ulcer pain, which were higher in the BD group. The differences observed in NFU were clinically irrelevant, as they were minor vs the untreated period. Additionally, these differences were absent at RT3 and RT12, suggesting they were not due to reduced long term efficacy in the BD group but rather to increased variability from the smaller sample size. Notably, the differences in NFU did not correlate with a higher number of oral or genital ulcers during those periods. Roflumilast significantly improved pain-NRS globally (BSD) and in BD and RAS conditions separately. However, it was more effective in patients with RAS.

Long-term efficacy was maintained throughout the year of treatment, indicating roflumilast could be a valid long-term therapeutic option. The 2 patients who discontinued roflumilast without transitioning to other treatments experienced a higher frequency of ulcers within weeks of withdrawal, which suggests the treatment was effective while active but lacks a prolonged post-treatment effect.

Roflumilast has demonstrated long-term safety in patients with COPD and does not require close monitoring or regular blood tests.12 However, real-world clinical studies report that up to 72% of patient's experience AEs, with 49–68% discontinuing treatment within the first year.12–14 In our study, 22 of 33 patients (66%) experienced AEs, most of which were mild-to-moderate and self-limited within the initial weeks of treatment or after dose increases. For non-self-limiting AEs, dose reduction or splitting the daily dose into two administrations was effective in improving tolerability. Only 3 patients experienced weight loss during the year of treatment, contrasting with findings in psoriasis, where an average weight loss of −4.0% (−3.2kg) was observed after 6 months.15 While maintenance doses below 500μg/day and divided dosing are not included in the roflumilast data sheet,16 the last approach is documented for other PDE4 inhibitors such as apremilast.17 In our experience, 5 patients who were unable to tolerate a single daily dose were able to tolerate a divided dosing regimen.

Seven patients (21.2%) discontinued roflumilast; only 2 cases (6.25%) due to AEs. Both discontinuations occurred during the initial weeks of treatment. One patient started at 250μg/day and the other at 500μg/day, a dosage not specified in the technical data sheet.16 The lower discontinuation rate due to AEs in our cohort may be attributed to the use of lower maintenance doses, as 21 of the 30 patients on long-term treatment (70%) remained on 125 or 250μg/day. These findings emphasize the importance of clearly explaining the expected AEs profile and its evolution, as recommended in COPD studies.12 Additionally, initiating treatment at low doses with gradual increases based on effectiveness and tolerance, or dividing the dose into two daily administrations, may improve tolerance and treatment adherence.

Although quality of life was not assessed with scales before starting roflumilast, 23 of the 25 patients who completed a 1-year regimen reported an average improvement of 9.4/10. Additionally, the patient who independently resumed roflumilast reported an improvement of 8.5/10. These subjective improvements align with the observed efficacy, as all studied parameters showed significant reductions vs the untreated period.

Conclusions- •

Roflumilast seems to be an effective and safe treatment for the long-term management of BSD characterized by predominantly oral and/or genital ulcerative symptoms.

- •

Roflumilast does not seem suitable as a first-line therapy for patients with a mucocutaneous phenotype experiencing frequent and/or moderate-to-severe flare-ups of erythema nodosum or significant extracutaneous symptoms.

- •

The genetic similarities in BSD seem to extend to therapeutic responses, with similar outcomes across different response variables.

- •

Initiating treatment at low doses with gradual increases based on tolerance and effectiveness, along with clear communication about the expected adverse effect profile, may improve treatment adherence.

- •

Splitting the roflumilast dose into two daily administrations, similar to the dosing recommendations for apremilast, may enhance tolerance and allow the use of higher doses vs a single daily dose.

This study has a limited sample size and is unblinded, which may introduce observer bias. The lack of a placebo control group means that part of the observed effect could be attributed to the placebo effect. The retrospective collection of some baseline data may be subject to recall bias.

FundingValencian territorial section of the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV).

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.