In 2010, wind energy coverage in Spain increased by 16%, making the country the world's fourth largest producer in a fast-developing industry that is also a source of employment. Occupational skin diseases in this field have received little attention. The present study aims to describe the main characteristics of skin diseases affecting workers in the wind energy industry and the allergens involved.

Material and methodsWe performed a descriptive, observational study of workers from the wind energy industry with suspected contact dermatitis who were referred to the occupational dermatology clinic of the National School of Occupational Medicine (Escuela Nacional de Medicina del Trabajo) between 2009 and 2011. We took both a clinical history and an occupational history, and patients underwent a physical examination and patch testing with the materials used in their work.

ResultsWe studied 10 workers (8 men, 2 women), with a mean age of 33.7 years. The main finding was dermatitis, which affected the face, eyelids, forearms, and hands. Sensitization to epoxy resins was detected in 4 workers, 1 of whom was also sensitized to epoxy curing agents. One worker was sensitized to bisphenol F resin but had a negative result with epoxy resin from the standard series. In the 5 remaining cases, the final diagnosis was irritant contact dermatitis due to fiberglass.

ConclusionsOccupational skin diseases are increasingly common in the wind energy industry. The main allergens are epoxy resins. Fiberglass tends to produce irritation.

En el año 2010 la energía eólica en España incrementó su capacidad de cobertura un 16%, lo que posiciona al país en el cuarto lugar del mundo en este sector industrial, de gran desarrollo económico y fuente de empleo. Las dermatosis profesionales en este campo han sido poco estudiadas. Con el presente estudio se pretende describir las principales características de la afectación cutánea en sus trabajadores y los alérgenos implicados.

Material y métodoSe realiza un estudio descriptivo y observacional de trabajadores de la industria eólica con sospecha de dermatitis de contacto remitidos a consulta de Dermatología Laboral de la Escuela Nacional de Medicina del Trabajo entre 2009 y 2011. Se realizó historia clínica, historia laboral, exploración física y pruebas epicutáneas según los materiales manipulados por estos trabajadores.

ResultadosSe estudiaron 10 trabajadores (8 hombres, 2 mujeres) pertenecientes a esta industria. La media de edad fue de 33,7 años. El cuadro principal fue eccema que afectaba a la cara, a los párpados, a los antebrazos y a las manos. En 4 trabajadores se encontró una sensibilización a resinas epoxi, uno de ellos presentó, además, sensibilización a sus endurecedores. Un paciente se encontraba sensibilizado a la resina de bisfenol F, con negatividad de la resina epoxi de la batería estándar. En los 5 casos restantes el diagnóstico final fue el de dermatitis de contacto irritativa por fibra de vidrio.

ConclusionesLas dermatosis ocupacionales en la industria eólica son cada vez más frecuentes. Las resinas epoxi son sus principales alérgenos, mientras que la fibra de vidrio suele producir cuadros irritativos.

Wind has been used as an energy source since ancient times, when people began to apply it to pump water, propel boats, and grind grains. The modern wind industry came into being in 1979 with the mass production of turbines moved by large blades, which have increased in diameter over time from 20-30m to the 90m currently used by the highest-output turbines (Fig. 1). During the last 10 years, world wind energy production has increased considerably, with the result that production now stands at 196 630 MW.1 In 2010, China was the world's leading wind energy producer, with Spain in fourth place after the United States and Germany.2 Spain has 889 wind farms with 18 933 turbines distributed throughout the country; the farms are located mainly in Castile and Leon, Castile-La Mancha, Galicia, and Andalusia. The highest installed capacity is in Castile and Leon.3

The advantages of wind energy are that it is renewable, nonpolluting, and easily obtained if the turbines are installed in a suitable location. Its main disadvantages, however, are the high cost of the aerogenerators, in which production of energy is intermittent, and the fact that the energy cannot be stored.4 Aerogenerators are manufactured mainly in Denmark, Portugal, Spain, and Germany. The materials used in their construction include carbon fiber and synthetic fiber (aramids), as well as epoxy resin and curing agents. The manufacturing process varies according to needs, and fiberglass is now replacing carbon fiber.5 An aerogenerator costs €2-3 million and has a half-life of 20 years.

People who work in the manufacture of wind turbines must use special protective clothing, gloves, and goggles to prevent exposure to these substances, which are irritants and sensitizing agents. Few studies have examined skin diseases in the wind turbine industry. Rasmusse et al.6 reported a prevalence of 10.9% for occupational allergic contact dermatitis; the allergen was epoxy resin in 60.6% of cases and epoxy curing agents in 37.9%. Our study aimed to describe the skin symptoms presented by these workers and the allergens causing occupational contact dermatitis in this industry.

Material and MethodsWe performed a descriptive observational study of patients working for companies that produced aerogenerators with suspected occupational contact dermatitis who were referred to the dermatology clinic of the National School of Occupational Medicine (Escuela Nacional de Medicina del Trabajo) in Madrid, Spain between 2009 and 2011. We took a general clinical history and occupational history, and patients underwent a physical examination. We studied the products to which the workers were exposed in their jobs by analyzing the product safety data sheets and conducting interviews with representatives of the company.

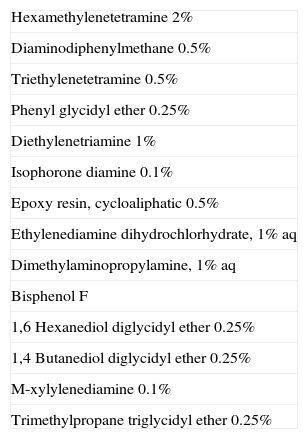

The patch tests applied were the standard series of the Spanish Contact Dermatitis and Skin Allergy Research Group (GEIDAC) and the epoxy resin series of Chemotechnique Diagnostics (Table 1). Other specific panels were used in some cases depending on the allergens specified on the product safety data sheet and in the clinical history. The patches were placed on the patient's back, where they remained under occlusion for 48hours. The results were read at 2, 3, and 6 days and reported according to the criteria of the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (+, ++, and +++).

Epoxy Resin Series of Chemotechnique Diagnostics.

| Hexamethylenetetramine 2% |

| Diaminodiphenylmethane 0.5% |

| Triethylenetetramine 0.5% |

| Phenyl glycidyl ether 0.25% |

| Diethylenetriamine 1% |

| Isophorone diamine 0.1% |

| Epoxy resin, cycloaliphatic 0.5% |

| Ethylenediamine dihydrochlorhydrate, 1% aq |

| Dimethylaminopropylamine, 1% aq |

| Bisphenol F |

| 1,6 Hexanediol diglycidyl ether 0.25% |

| 1,4 Butanediol diglycidyl ether 0.25% |

| M-xylylenediamine 0.1% |

| Trimethylpropane triglycidyl ether 0.25% |

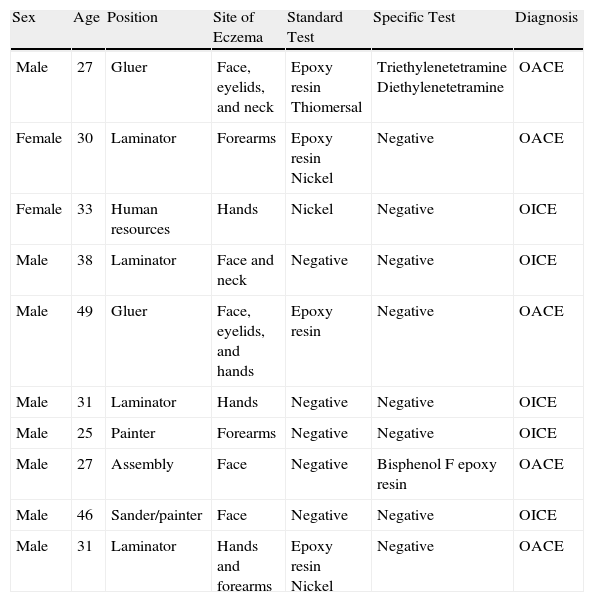

During the study period, 10 patients from the aerogenerator manufacturing industry were seen (8 men and 2 women; mean age, 33.7 years [range, 25.0-46.0] years). They worked as painters, laminators, and gluers (Table 2). Four of the patients worked for Gamesa (a Spanish company employing 7200 workers) and 4 for Vestas (a Danish company with 1600 workers in Spain). The remaining 2 workers were employed by subsidiaries of Gamesa and Vestas.

General Characteristics of the Patients.

| Sex | Age | Position | Site of Eczema | Standard Test | Specific Test | Diagnosis |

| Male | 27 | Gluer | Face, eyelids, and neck | Epoxy resin Thiomersal | Triethylenetetramine Diethylenetetramine | OACE |

| Female | 30 | Laminator | Forearms | Epoxy resin Nickel | Negative | OACE |

| Female | 33 | Human resources | Hands | Nickel | Negative | OICE |

| Male | 38 | Laminator | Face and neck | Negative | Negative | OICE |

| Male | 49 | Gluer | Face, eyelids, and hands | Epoxy resin | Negative | OACE |

| Male | 31 | Laminator | Hands | Negative | Negative | OICE |

| Male | 25 | Painter | Forearms | Negative | Negative | OICE |

| Male | 27 | Assembly | Face | Negative | Bisphenol F epoxy resin | OACE |

| Male | 46 | Sander/painter | Face | Negative | Negative | OICE |

| Male | 31 | Laminator | Hands and forearms | Epoxy resin Nickel | Negative | OACE |

Abbreviations: OACE, occupational allergic contact eczema; OICE, occupational irritant contact eczema.

The product safety data sheets presented by the workers indicated the presence of lacquers, form releasers, adhesives, and resins among the substances generally handled in the workplace. These chemicals are usually referred to on the safety data sheet as bisphenol A, 1,6 hexanediol diglycidyl ether, and sometimes more generically as synthetic resins, epoxy resins, or resin solutions.

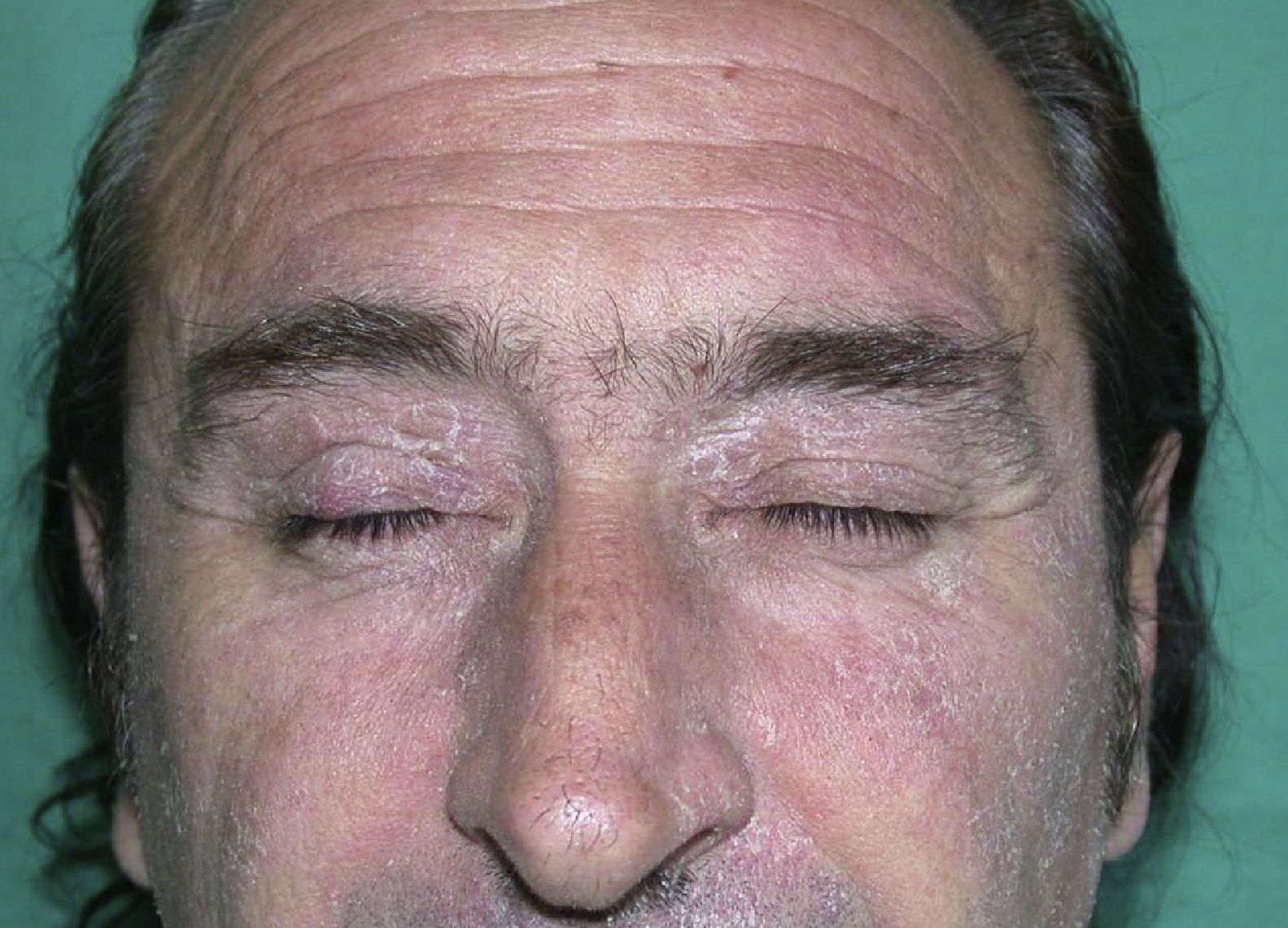

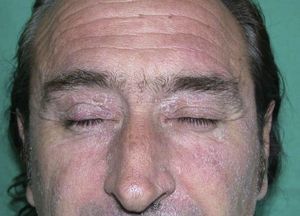

The workers had eczematous lesions affecting the face and eyebrows (4 patients), as well as the hands, forearms, or both (7 patients) (Fig. 2). The patch tests revealed sensitization to epoxy resin from the standard series in 4 workers, 1 of whom was also sensitized to the curing agents triethylenetetramine and diethylenetetramine. One patient, whose test result was negative with the standard series, was sensitized to the epoxy resin bisphenol F from the epoxy resin series (Chemotechnique Diagnostics) (Fig. 3). Given the location of the lesions (sites affected by airborne allergens) and the allergens in the workplace, patients who did not show sensitization in the standard series were diagnosed with irritant contact dermatitis induced by fiberglass.

Consistent with our findings, 5 workers were diagnosed with occupational allergic contact eczema and 5 with occupational irritant contact eczema.

DiscussionThe search for new sources of renewable energy has led to the production of wind farms. Consequently, aerogenerator manufacturers have been set up in Spain, which is now the second largest producer of wind energy in Europe and the fourth largest in the world. These companies provide employment to thousands of workers, and occupational skin diseases have been recorded in this novel industry. The blades of the turbines are manufactured using an outer coating of epoxy resin. The structure is strengthened using fiberglass, which may be previously impregnated with epoxy resin, to which curing agents are added in order to catalyze the resins. The coating and prepregs are hardened at high temperatures using autoclaves. The production process consists of the following steps: cutting of prepregs; construction of blades, beams, and assembly parts; and finishing.6,7

Epoxy resins are used as insulators and adhesives, as well as coatings and paints. These substances are potent allergens and the main cause of occupational allergic contact eczema, as is the case in the aerospace industry.8 An epidemiologic study by Ponté et al.5 in a Danish company specializing in the production of aerogenerators analyzed 603 workers and found that 10.9% had occupational allergic contact eczema, indicating that the percentage of patients sensitized to epoxy resins was extremely high. The main allergens were the epoxy resins bisphenol A (10.5%) and bisphenol F (8%).

A study by Conde-Salazar et al.9 performed in the aeronautical industry, where the manufacturing process is similar to that used in the wind turbine industry, revealed that 6.5% of workers presented occupational allergic contact eczema due to sensitization to bisphenol A.

Our results show that half of the patients analyzed were sensitized to epoxy resins; we consider this prevalence to be high for our population. We must also remember that not all patients are sent to our reference center for patch testing, because the skin manifestations are often very subtle, because no disease is suspected, or even because the patient shows little concern for his/her condition. As was the case in the study of Rasmusse et al.,6 the sensitizing allergens were epoxy resins, although in some cases, the sensitizing agents were bisphenol F or curing agents such as triethylenetetramine and diethylenetetramine. Bisphenol F was previously reported to be an allergen in patients working in the aeronautical industry10 or in the manufacture of adhesives11 and can go completely unnoticed if its involvement in specific types of eczema is not suspected.

Location on the face, neck, hands, and forearms suggests the presence of an airborne mechanism, as occurs in irritant and allergic contact eczema caused by epoxy resins.12 The association between eczema and physical presence in the workplace (improvement during leave or vacation and recurrence on returning to work) is an important indicator of the involvement of this resin in the disease.

Half of the workers referred to our department were diagnosed with occupational irritant contact eczema caused by exposure to fiberglass, a material that is widely used in the manufacture of aerogenerators. Fiberglass-induced skin disease is frequent in the construction industry,13 as the small particles that penetrate the stratum corneum lead to irritation and have pruritus as their main and almost only manifestation. Nogueira et al.14 published the case of a worker in the wind industry in whom sensitization to fiberglass (not irritation) was thought to be the cause of localized eczema on the face, neck, and forearms. However, the positive patch test result for epoxy resins found by those authors could also point to a diagnosis of occupational allergic contact eczema caused by epoxy resins, together with occupational irritant contact eczema caused by fiberglass.

ConclusionEpoxy resins are one of the most common allergens in industry in general and in the plastics industry in particular. As a new high-technology activity, the wind turbine industry uses these substances in the manufacture of aerogenerators; therefore, occupational skin diseases caused by contact with epoxy resins are likely to become increasingly common.

We believe that workers in the wind turbine industry should undergo patch testing with epoxy resin series, as well as the standard series, to enable the detection of allergens that are common in this industry and that are not always indicated on the product safety data sheets. Both allergic contact eczema caused by epoxy resins and irritant contact eczema caused by fiberglass are a frequent finding in these patients and usually present as diseases caused by airborne allergens.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Lárraga-Piñones G, et al. Dermatitis de contacto profesional en la industria eólica. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:905–9.