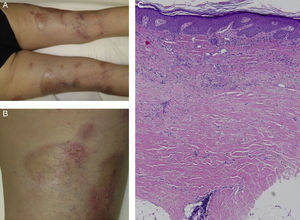

We report the case of a 63-year-old woman with a history of pustular and plaque psoriasis that had first appeared 4 years earlier. The patient had previously received treatment with topical clobetasol, calcipotriene-betamethasone, and oral acitretin at a dose of 25mg/d, as well as narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Because of the persistence of the lesions, we decided to initiate systemic therapy with ustekinumab. At a follow-up appointment 6 months after the start of biologic therapy, the psoriasis had improved. However, on the back of both legs, several hard, pearly plaques with violaceous edges had appeared in lightened areas of older psoriasis plaques (Figures 1A and 1B). Localized morphea was clinically suspected. A biopsy specimen was taken from one of the lesions and histologic examination resulted in a diagnosis of morphea (Figure 1C).

Clinical and histologic images of the patient. A, Hard, pearly plaques with violaceous edges (lilac ring) underneath older psoriasis plaques on the lower limbs. B, More detailed image showing the coexistence of morpheaform plaques and erythematous plaques with a psoriasiform appearance. C, Densely packed collagen bands in the deep reticular dermis, parallel to the dermoepidermal junction (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification×10).

The coexistence of morphea and psoriasis is a rare finding in routine clinical practice. To date, 19 cases have been described in the literature (Table 1).1–8 Nevertheless, psoriasis is the autoimmune disease most frequently associated with morphea, accounting for 11.6% of cases in which an immune-mediated disease occurs in conjunction with morphea.1 The small number of case reports and the lack of knowledge about the pathophysiologic mechanisms of both entities make it difficult to understand this phenomenon. Nevertheless, we have developed several hypotheses.

First, our patient could have developed morphea concomitantly with psoriasis due to a common immunologic basis of the 2 entities. Multiple helper T (TH) cell differentiation pathways besides those mentioned in this article have been described; 3 such pathways are of special interest in our case.9,10 The TH1 pathway and its associated interleukins (IL)—IL-2, IL-12, and interferon (IFN) γ—regulate cellular immunity and are associated with conditions such as psoriasis, inflammatory bowel disease, and graft-versus-host disease. The TH2 pathway—which is associated with IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13—is involved in humoral immunity and is, to date, the main pathway known to be involved in morphea. A third, recently described pathway—TH17, associated with IL-17, IL-22, and IL-23—is believed to play a more important role in immune-mediated diseases. This pathway appears to interact with the 2 pathways mentioned above. Several authors have argued that dysregulation of these pathways could be responsible for the coexistence of morphea and psoriasis in the same patient.3,4,11 The immunologic environment of psoriasis, dominated by the TH1 pathway, could mask manifestations of sclerosing diseases such as morphea, which are dominated by TH2. Along these lines, Bezalel et al.11 reported the case of a patient who developed plaques of morphea while receiving IFN treatment for multiple sclerosis. The authors concluded that IFN-induced activation of the TH2/IL-4 pathway could have triggered the appearance of morphealike lesions.

The immunogenic hypothesis is also supported by the fact that antinuclear antibody positivity is more prevalent in patients with both psoriasis and morphea.4

Taking into account the information outlined above, it is also possible that the introduction of ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 monoclonal IgG1 antibody, could have blocked the TH1 signaling pathway, leading to increased expression of TH2 and consequently the formation of morphea plaques in a predisposed patient. Therefore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the development of morphea in our patient was an adverse effect of ustekinumab. This drug was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in June 2008. We have found no reports to date of ustekinumab being associated with the development of morphea. However, an association between etanercept and morphea plaques—extending from the injection site—has been reported in a patient with psoriasis.6

Finally, in a predisposed patient, the psoriasis itself could have triggered the morphea—an example of the Wolf isotopic response.

In conclusion, we cannot rule out any of the 3 hypotheses: immunologic, pharmacologic, and the Wolf isotopic response. Likewise, it is impossible to know whether the morphea was previously present under the psoriasis plaques. Nevertheless, we believe that the 3 hypotheses are not mutually exclusive; the interaction of the drug with an altered immune system could have caused the development of morphea in our patient. Reports of similar new cases and a better understanding of the pathophysiologic mechanisms of both diseases could shed light on this enigma.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Corral Magaña O. Morfea en una paciente con psoriasis en tratamiento con ustekinumab: ¿coexistencia o efecto adverso?. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:486–488.