Vasculitis is a rare complication of cocaine abuse and poses significant diagnostic and management problems. We report a case of this type of vasculitis.

A 45-year-old woman with a history of cocaine abuse from age 23 years consulted because of a 20-day history of a widespread skin condition that affected practically the whole body surface, was accompanied by fever and intense pain, and prevented her from walking. At the time of admission, the patient was underweight, had facies dolorosa, normal vital signs, and dry mucosas. Physical examination revealed multiple ulcers of varying shape and size, with a purulent, foul-smelling exudate; several were covered by necrotic slough (Fig. 1).

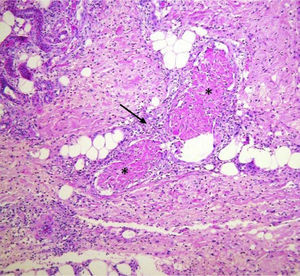

Additional tests, based on a suspected clinical diagnosis of systemic vasculitis, gave the following results: white blood cell count, 12 500/μL; hemoglobin, 9.8g/dL; reactive thrombocytosis, 658 000/μL; hypoalbuminemia, 2.0g/dL; alanine aminotransferase, 68 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 62 U/L; γ-glutamyltransferase, 181 U/L; alkaline phosphatase, 326 U/L; creatinine clearance, 88.3mL/min with renal function of 86.6%; C-reactive protein, 1.40mg/dL; a negative Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test, negative rheumatoid factor; antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (c-ANCA), 1:40; perinuclear (p) ANCA, 1:2560 U/mL; p-ANCA antilactoferrin, 48.2 U/mL; culture of the skin exudate, Escherichia coli; positive total hepatitis A virus antibody; negative anti-hepatitis B and anti-hepatitis C virus antibodies; negative human immunodeficiency virus (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). Skin biopsy revealed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 2).

The otorhinolaryngology department reported perforation of the cartilaginous portion of the nasal septum, confirmed by computed tomography, but biopsy of the nasal mucosa only revealed chronic inflammation. The psychiatry department diagnosed the patient as having a mixed personality disorder and treatment was initiated with amitriptyline, perphenazine, and diazepam. The general surgery department then performed surgical debridement of the ulcers and escharectomy. The patient was treated with antibiotics (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 160/800mg, administered intravenously every 12hours for 14 days), analgesics, and thalidomide (100mg/d); prednisone (0.5mg/kg) was added after achieving control of the infection. The response was satisfactory and the patient was discharged after 37 days, with the presence of granulation tissue and partial reepithelialization of the ulcerated areas. Diagnosis at discharge was cocaine-related vasculitis based on the clinical findings, histopathological study, the positivity of serum markers (p-ANCA and lactoferrin), a history of long-term consumption of the drug, and the exclusion of other causes.

Follow-up confirmed the reepithelialization of most lesions, which developed into hypertrophic scars and retractile keloids, currently awaiting surgical treatment by the plastic surgery department (Fig. 3).

Cocaine consumption is increasing worldwide, leading to a rise in related diseases. The spectrum of skin lesions caused by cocaine is broad and has been related to digital vasospasm, bullous diseases, small- and medium-vessel vasculitis, which present as purpura, necrotizing vasculitis, urticarial vasculitis, ulcers, livedo reticularis, Buerger disease, pyoderma gangrenosum, and gangrene.1,2 Some authors hold levamisole, an adulterant found in the end product, responsible for the damage in cases involving microvascular thrombosis and neutropenia.3 There are reports of cocaine consumption in patients with Wegener granulomatosis,4 and since both may cause midline destructive lesions of the face, distinguishing between them can be difficult. In our patient, the absence of granulomatous vasculitis of the respiratory tract, renal involvement, and high titers of c-ANCA enabled us to rule out this possibility.

The study protocol for cocaine-related vasculitis is identical to drug-related vasculitis and includes a blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, routine biochemistry, chest x-ray, urinalysis, liver function tests, and fecal occult blood. More specific studies should subsequently be considered, such as histopathology with or without direct immunofluorescence, anticardiolipin antibodies, homocysteine levels, proteins S and C, and cryoglobulins. Serum levels of ANCA, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, complement, and hepatitis B and C virus antibodies should also be determined, together with human immunodeficiency virus serology.5

The case presented here was a drug-dependent patient whose clinical lesions were compatible with necrotizing vasculitis confirmed by histopathology, with a diagnosis of an ANCA-positive cutaneous vasculitis (p-ANCA, 1:2560 U/mL, antilactoferrin antibodies, 48.2 U/mL). The differential diagnosis included other forms of ANCA-positive small-vessel vasculitis. The role of ANCA in the pathogenesis of vasculitis is still unclear. One hypothesis suggests that ANCA stimulate neutrophil degranulation, activation, and apoptosis, leading to direct and indirect endothelial damage.6 Drug-induced ANCA show a perinuclear fluorescence pattern (p-ANCA) and positivity to several antigens (myeloperoxidase, cathepsin G, proteinase 3, azurocidin, bactericidal/permeability-increasing protein, lactoferrin, and human neutrophil elastase). Reports in the literature suggest that the presence of lactoferrin and human neutrophil elastase supports the diagnosis of a cocaine-related syndrome.3,7

The management of these patients is still a matter of debate, but good outcomes have been reported with the use of systemic steroids, nonsteroidal immunosuppressants, antihistamines, dapsone, pentoxifylline, and intravenous immunoglobulin.8 Our patient stopped taking cocaine and was treated with thalidomide and systemic steroids. Although the outcome was excellent, significant scarring could not be avoided.

Please cite this article as: Salas-Espíndola Y, et al. Vasculitis leucocitoclástica asociada a consumo de cocaína. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2011;102:825-826.