In their recently published article in Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas, Conde-Salazar et al1 pose the question of whether José Eugenio de Olavide Landazábal (1836–1901) is the person depicted on “Plate IV in the section on spontaneous local skin diseases or deformities,”† an illustration that is captioned “disseminated canities” (canicie diseminada) in Dr Olavide’s own Atlas of Clinical Images of the Skin and Skin Diseases.2

The authors reach the conclusion that this portrait, painted and reproduced as a color lithograph by José Acevedo (fl 1850–1905), is indeed of the author of the Atlas. As evidence of their “discovery” of an image of Olavide, they compare it with several known portraits of him. They also point to his signature on the illustration in numerous copies of the Atlas.

In addition, they show the results of superimposing a digitized version of the illustration onto a digitized photograph published on page 12 of the Barcelona magazine Iris on March 16, 1901, stating that the photographer is “unknown” (anónimo). The authors point out the similarity between the clothing shown in the photograph and the illustration, stating, “We can say almost certainly that the portrait carefully drawn and reproduced by José Acevedo for the Atlas was based on this photograph of Olavide.”

In their conclusion Conde-Salazar et al1 note that placing an author’s portrait on one of the opening pages of a book was not unusual in this period. What they find striking about this “apparent portrait,” is that it appears in the middle of Olavide’s work, presenting the author as just one patient among others.

We agree that the illustration depicts Dr Olavide and that it was based on the photograph published in Iris. The lithograph is not presented as a realistic portrait, however, but rather as an artist’s interpretation to justify its inclusion in the Atlas as an illustration of a so-called disease — even though canities is not a diagnosis as such. The aim of presenting himself as just another patient explains why the author chose to insert a color plate in the middle of the volume, in one of the sections on disease categories, rather than place a photograph at the beginning.

This story was widely known in Olavide’s time, and the fact that it was nearly forgotten shows how little attention is paid to the history of dermatology in Spain. Apart from traces left in oral tradition, there are simple ways to confirm the veracity of the story and, in the process, expand on our knowledge of Olavide.

The photograph referred to by Conde Salazar et al1 appeared in Iris in the context of an obituary3 whose text reads as follows: “Dr Olavide left a monumental work, his Iconographic treatise on skin diseases, with its magnificent color illustrations showing the innumerable signs of diseases in patients. Unusually, a portrait of the author appears in the section on canities, by which means the distinguished dermatologist chose to present himself as an example of a patient, even though he only suffered the mild condition of graying hair.”

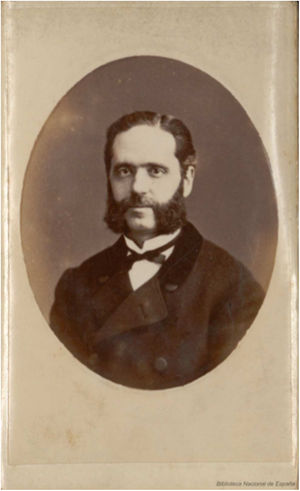

The quality of the photograph reproduced in Iris is poor, but at least one original print has been preserved. It is one of the best images — if not the best — we have of Dr Olavide (Fig. 1).

The photographer who took the picture, Eusebio Juliá y García-Núñez (1826–1895), was very well known and active in Madrid between 1855 and 1881. The original, which was acquired by Spain’s national library (Biblioteca Nacional de España) in 1997, is an albumen silver print in the form of an oval measuring 69 × 54 mm on a typical visiting card of the period.4,5 It is dated between 1879 and 1881.

It is important to remember that although Olavide’s Atlas bears the publication date of 1873, the illustrations were produced in installments that appeared until 1880 or 1881; thus the dates of the photograph and the Atlas are consistent.6,7

We applaud the efforts of dermatologists who are bringing the neglected history of Spanish dermatology to the forefront once again, and we encourage them to recover the wealth of documentary and illustrative material at risk of being lost.

We mention in passing that the plate that follows the portrait of Olavide in the Atlas and that shares its special features — the oval format typical of portraits of the time, a figure dressed in elegant apparel, etc, and the lack of an accompanying case history in the text — is a portrait of Eusebio Castelo Serra (1825–1892). But as Kipling would say, that is another story.

Please cite this article as: Fonseca Capdevila E. José Eugenio de Olavide Landazábal: fotografías y litografías. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:485–486.

Translator’s note: The texts in quotes in this paragraph and any others that come from the article being discussed (Conde-Salazar et al1) were taken from the open-access English version of that article (DOI: 10.1016/j.adengl.2019.09.001). However, the quote in the seventh paragraph, from reference 3, is from this translator; in it, Olavide’s Atlas is referred to as his iconographic treatise, shown in this translation in italics and with a capital letter as in the original.