In the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th, atlases were the only widely available tools for studying dermatology. The specialty did not yet exist as such at the time, but its subject matter was studied briefly within the syllabus for surgical pathology, taught by instructors who were not experts in skin diseases and without recourse to clinical contact with patients.

Medical students and physicians occasionally filled the gap with extracurricular courses, which might be organized by well-known specialists like José Olavide, Benito Hernando, Ramón de la Sota and others, or students might visit the Hospital San Juan de Dios, as Pío Baroja describes in the novel Tree of Knowledge (El Árbol de la Ciencia).1 On some occasions, the Olavide Museum of moulages and wax figures served as the setting for classes or simply as a place where skin lesions could be seen more instructively.

However, most students and physicians filled the instructional gap by consulting textbooks published in Spain or imported from abroad, mainly from France. Most books contained only theoretical material, so illustrated clinical atlases or reproductions of some type were necessary to show what the most prevalent types of lesions looked like. One of the first of these resources to appear was the 1864 Atlas of Venereal and Syphilitic Diseases (Atlas de Enfermedades Venéreas y Sifilíticas) by José Díaz Benito.2 However, the later publication of Olavide's General Dermatology and Illustrated Atlas of Skin Diseases, or Dermatoses (Dermatología General y Clínica Iconográfica de las Enfermedades de la Piel o Dermatosis)3 was a major event in Spanish dermatology. This work made an impact in spite of its rather inconvenient initial appearance in several installments between 1871 and 1881 and in spite of its price, which was set so high that it was unattainable not only for students but also for most practicing physicians. This situation encouraged the publication of other dermatology atlases, such as those of José Ginés Partagás (1880),4 Jerónimo Pérez Ortiz (1886),5 Ramón de la Sota y Lastra (1886),6 and Eusebio Oyarzábal (1911).7 All of these works summarized Olavide's, were sold at lower prices, and had fewer illustrations of inferior quality. Some plates had clear deficiencies. The most interesting thing about all of them was that their authors cited Olavide as their mentor and, in some cases, their illustrations were depictions of the Olavide Museum's wax figures or moulages, which have recently been recovered.

An edition of Jerónimo Pérez Ortiz's Album of Clinical Dermatology (Álbum Clínico de Dermatología)5 was recently acquired by the Spanish Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (AEDV) for the association's Olavide Museum. This author's work has been cited in previous publications,8,9 and the particular album in question could be described as an economical, abridged version of Olavide's work. We prepared this paper about the book because few are aware of its interesting content.

The Author's LifePérez Ortiz, born in Madrid in 1851, was a follower of Olavide. He was also a great friend and brought his mentor several patients whose cases were included in Olavide's Illustrated Atlas. His medical career unfolded mainly in the military. As was true for many so-called dermatologists of his time, Pérez Ortiz's true specialty was the closely related one of urology, and he was recognized as one of the founders of the military health system's school of urology. An account of his military and medical career can be found in the thesis of Fernando Martin Laborda.10

Pérez Ortiz, who was assigned to various military hospitals and was decorated for his service, earned his initial appointment through a competitive examination and selection process. He was awarded the position of military physician by the government of the Spanish Republic on August 31, 1873, after which he was posted to many different locations and served with various regiments and battalions over the next 12 years. Those were the years Pérez Ortiz spent acquiring experience in war surgery and in which, as a decorated soldier, he was promoted based on merit.

When on March 28, 1882, he was assigned to the Battalion of Hunters of Ciudad Rodrigo, quartered in Madrid, he took up residence in the capital. On February 23, 1886, he was reassigned to the city's military hospital (Hospital Militar), where he initially took charge of a medical clinic. After a time working in the pathology division (Instituto Anatomopatológico), he began to practice in the hospital's venereal disease clinics. His work on his 1886 Album of Clinical Dermatology5 earned him the Cross of the Order of Charles III, awarded at the end of 1887. At the time the book was published, Pérez Ortiz was chief of the military hospital's venereal disease clinic. Later, he was named head of surgery at the Hospital Militar de Carabanchel, in Madrid, and from that position he published several papers on urology in the military health system's journal Sanidad Militar.

Pérez Ortiz also practiced outside the military, at his private clinic at Calle Huertas, number 67, which he advertised as specializing in skin and syphilitic diseases (Fig. 1); in addition, he attended patients at a charitable facility (Casa Refugio). He was known mainly as a surgeon and urologist, but he taught a course on cancer of the penis organized by the Spanish Academy of Physicians and Surgeons (Academia Médico Quirúrgica Española) in 1890–1891.

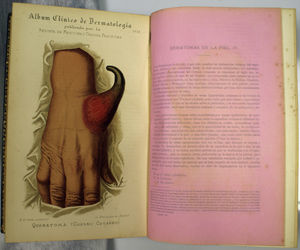

The AlbumThe book appeared in 1886 and was subtitled Lithographic Illustrations of Skin Diseases (Fig. 2). The publishing house's imprint showed it belonged to a journal on practical aspects of medicine and surgery (Revista de Medicina y Cirugía Prácticas), domiciled in Madrid at Calle Caballero de Gracia, number 9. The author was named as Don Jerónimo Pérez Ortiz and identified as a military physician in charge of the departments of venereal and syphilitic diseases at the armed forces’ hospital in Madrid. In the announcement published in the Revista de Medicina y Cirugía Prácticas, it is noted that the volume was awarded a prize by Madrid's Royal Academy of Medicine: This album—which complements the clinical instruction on skin diseases of Dr E. Guibout—contains 64 lithographs illustrating the same number of cases of skin diseases documented in the clinic of Dr Olavide at Hospital de San Juan de Dios and in the dermatologic clinic of Dr Pérez Ortiz. They are skillfully drawn by Mr Eusebio de Letre. Each illustration is accompanied by 4 pages of text giving an account of the history, description, and treatment of each case.

The album sold for 80 pesetas to the journal's subscribers who lived in Madrid; 85 pesetas to those who lived outside the capital; 110 pesetas to those in Cuba, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico; and 125 to purchasers in other countries. The contents of the volume's 242 pages are divided as follows:

1. In a prologue of 2 pages, dated July 1, 1886, Madrid, the author explains the reason for the publication: On giving life to this album on skin diseases, our sole intention was to spread a type of knowledge about which physicians in our country know little. That this is the case should come as no surprise, given that dermatology is hardly taught at all in Spanish medical schools, undoubtedly because the subject of surgical pathology itself is so extensive that all its aspects cannot be covered in the short space of 8 months.

Also pointing out that this album is more economical than others on the market (referring to Olavide's atlas), the author thanks Don Rafael Ulecia y Cardona, a fellow disciple of Olavide and the editor and owner of the Revista de Medicina y Cirugía Prácticas. Pérez Ortiz also remarks that his colleague “has incurred great expense in publishing a volume of this type.”

2. A series of brief accounts of aspects of general dermatology (called “notions”) contains the following sections: 1) History, classification and schools; 2) Anatomy and physiology of the skin; 3) Signs and symptoms of skin conditions, in 4 groups; 4) Clinical course, progression, and prognosis in skin diseases; and 5) Treatments. This part of the book also contains 4 plates showing the normal histology of the skin.

The album generally follows the terminology used by Pierre Antoine Ernest Bazin to explain diseases such as scrofulous diathesis or herpetic conditions. Olavide was the most prominent proponent of this school in Spain, but other perspectives on dermatology are also taken into consideration, as Pérez Ortiz alludes to both the French and German schools when explaining a disease from more than a single point of view. An example can be found in his notes on a case diagnosed as bald ringworm (alopecia areata): For the French school, and in our own country's approach, represented by the illustrious dermatologist Dr Olavide, bald ringworm is a phytoparasitic disease. For the German and English schools, this parasitic disease is no more than a nervous condition caused by intense neuralgias followed by hair loss.

The following title appears above all the illustrations: “Album of Clinical Dermatology published by the Revista de Medicina y Cirugía Prácticas”; the plate number appears in the upper right-hand margin. Each illustration's specific title is centered underneath. The book contains 60 illustrations (Table 1), each accompanied by a case description of 2 to 4 pages which gives the patient's medical history, diagnosis, treatment, and clinical course. The reporting style is very similar to that of the case notes accompanying the wax figures in the Olavide Museum. Along with the description of the patient's disease, the author explains the opinions of various physicians and the treatments to be prescribed, occasionally interjecting observations based on his own experience.

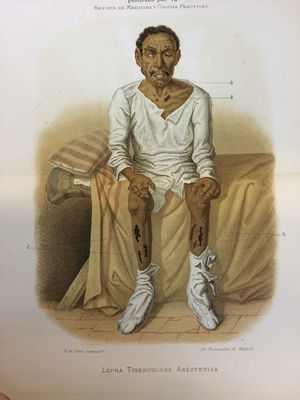

List of Illustrations in the Album of Clínical Dermatology.

| 1. Malignant scrofulides. Scrofulous rhinoscleroma. (HSJD, Olavide, ward 5, bed 8) |

| 2. Elephantiasis of the Arabs. (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 3. Bald ringworm. (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 4. Chronic herpetic eczema. (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz, 1883) |

| 5. Congenital nevus (telangiectasia). (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 6. Rheumatic psoriasis. (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 7. Eczema rubrum. (HSJD, Olavide, 1881) |

| 8. Herpetic lichen. (HSJD, Olavide) |

| 9. Chronic rheumatic lichen. (HSJD, Olavide, 1881) |

| 10. Acne rosacea. (Private clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 11. Generalized ichthyosis. (HSJD, Olavide, 1881) |

| 12. Vitiligo. (Military hospital) |

| 13. Rupiform scrofulide (Hospital Nuestra Señora de la Concepción, Pérez Ortiz) |

| 14. Pellagrous erythema: pellagra. (HSJD, Olavide) |

| 15. Mollusciform fibroma (University teaching hospital clinic) |

| 16. Varicose ulcer (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 17. Typical tinea capitis lesions (HSJD, Olavide) |

| 18. Pustular scabies (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 19. Generalized pruritic herpes eruption (HSJD, Olavide, bed 4, women's ward 13) |

| 20. Tubercular ulcerated scrofulides (lupus) (HSJD, Olavide) |

| 21. Acute urticaria (at one stage) (Private clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 22. Tinea tonsurans (first stage). (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 23. Confluent smallpox (Military hospital) |

| 24. Parasitic pityriasis versicolor (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 25. Acute erysipela (pseudoexanthema) (Private clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 26. Vaccination pustule, 6th day. (Vaccination institute) |

| 27. Hemorrhagic purpura (Hospital General) |

| 28. Scrofulous eczema (impetigo) (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 29. Prominent rupia (Clinic of Fernández Losada) |

| 30. Acute generalized pemphigus (Clinic of Fernández Losada) |

| 31. Anthrax (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 32. Generalized psoriasis (herpetic) (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 33. Herpetic sycosis (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 34. Scarlet fever (Private clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 35. Herpetic pityriasis (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 36. Erythema, chilblains (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 37. Macula (nevus spilus) (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

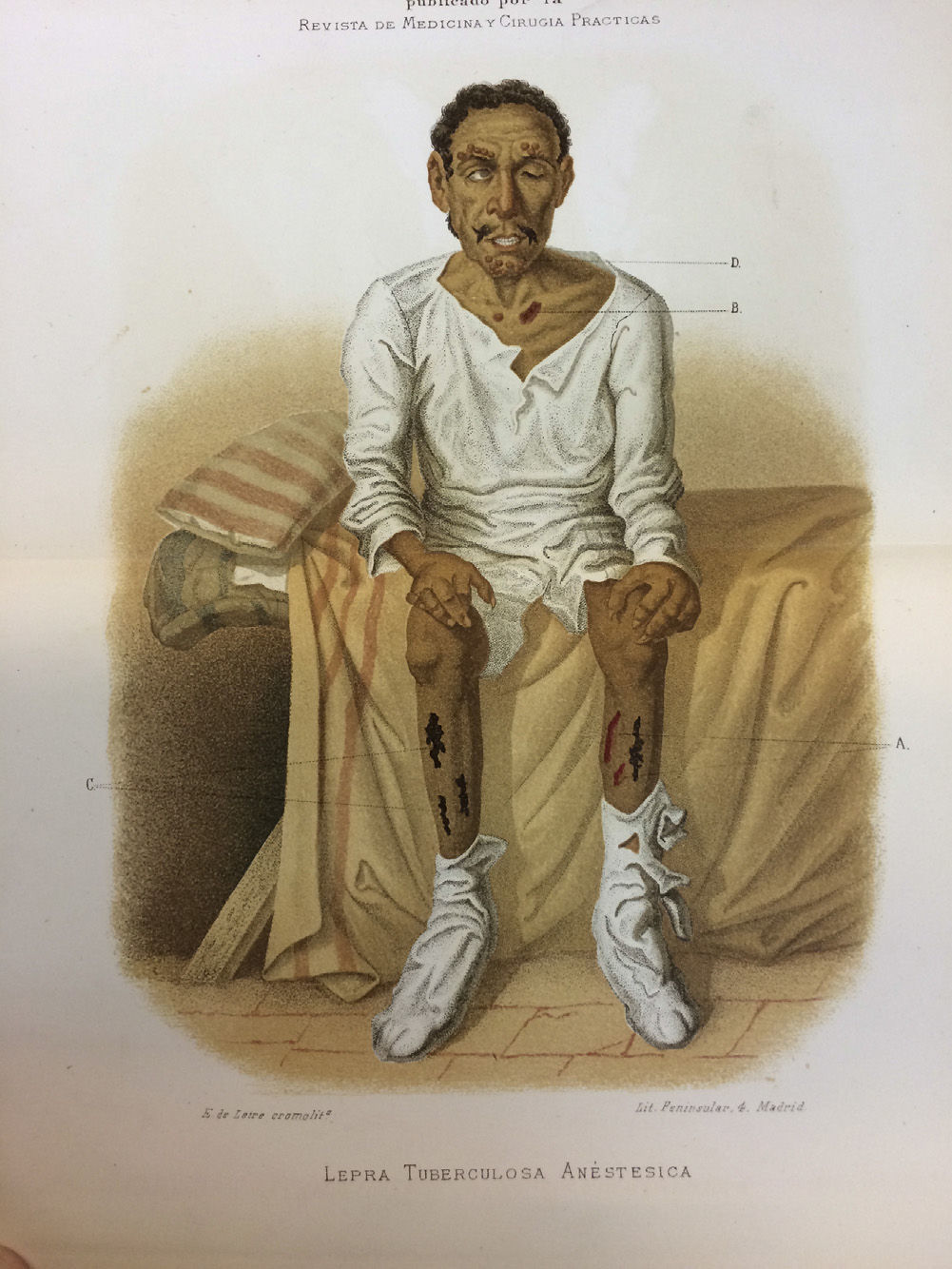

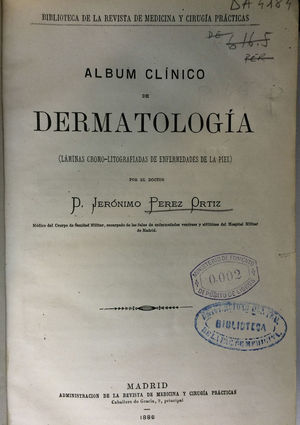

| 38–39. Anesthetic tuberculoid leprosy (double-page spread) (Olavide and Pérez Ortiz, 1882; highly illustrative history) |

| 40. Congenital leucoderma (albinism) (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 41. Exfoliative malignant herpetide (HSJD, Olavide, 1879) |

| 42. Herpes labialis (hydroa febrilis) (Pérez Ortiz) |

| 43. Ecthyma (self-inflicted) (Military Hospital) |

| 44. Confluent measles (eruptive stage) (Private clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 45. Herpes zoster (neuritic) (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz?) |

| 46. Addison's disease (Military hospital) |

| 47. Pityriasis nigricans (Public charity clinic [Casa Refugio]) (Pérez Ortiz, 1884) |

| 48. Rosacea (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 49. Chicken pox (Private clinic of Pérez Ortiz) |

| 50. Skin cancer (carcinoma) (Hospital Civil Huesca, Dr Gardeta, 1879) |

| 51. Hydrargyria vesicles (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz, 1885) |

| 52. Tuberculous skin abscesses (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz, 1885) |

| 53. Polish plica Copied from Alibert [Translator's note: Jean-Louis Alibert] |

| 54. Giant lipoma (Clinic of Pérez Ortiz, 1883) |

| 55. Pian (Copied from Alibert) [Translator's note: pian fungoides, later termed mycosis fungoides] |

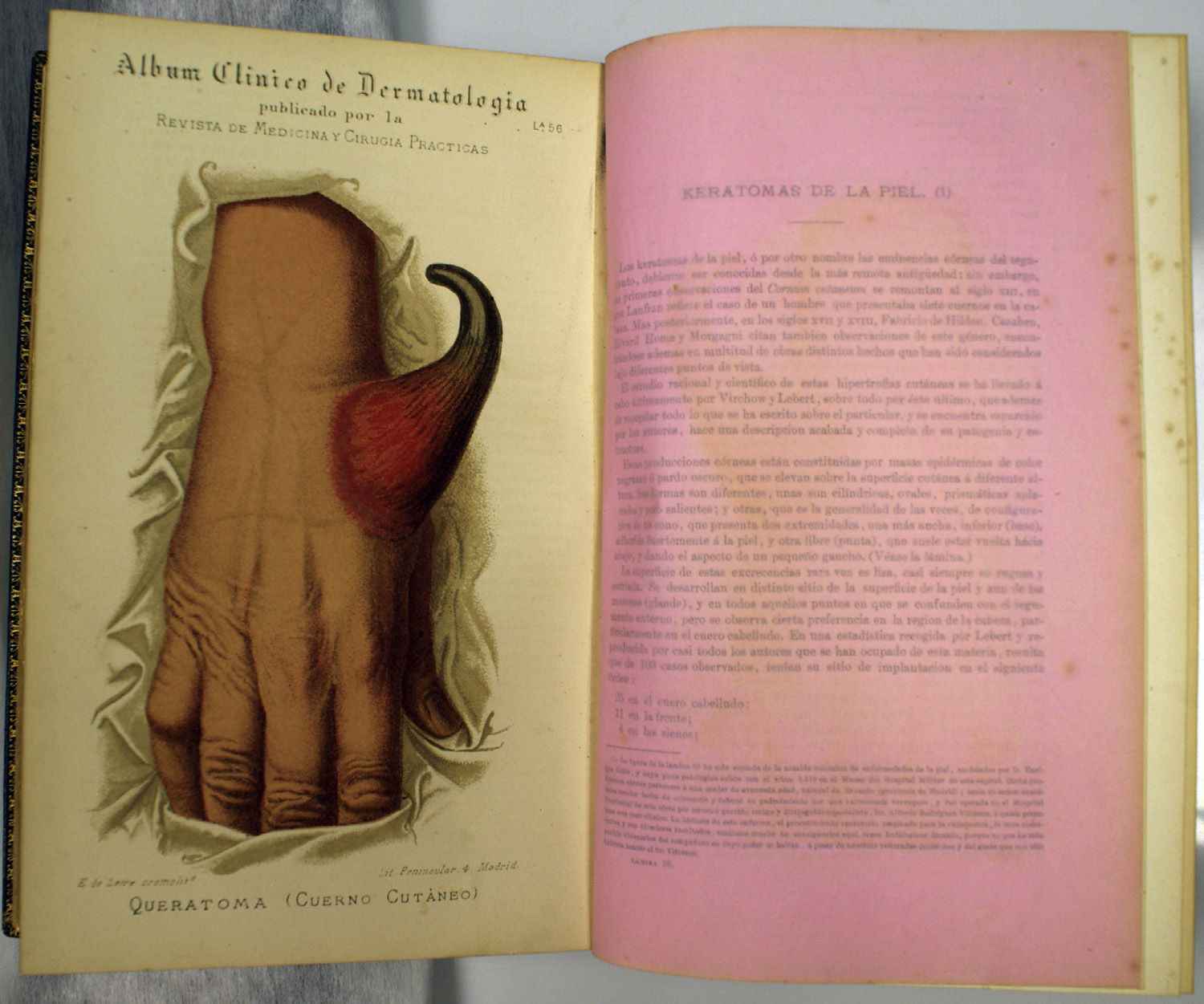

| 56. Keratoma (cutaneous horn) (Copied from figure number 1119 by Enrique Zofío Dávila in the military hospital's museum) |

| 57. Skin parasites (mite, Sarcoptes scabiei, variety hominis) |

| 58. Skin parasites (mite, Demodex folliculorum; phytoparasite, Leptus autumnalis) |

| 59. Skin parasites (bed bug, or chinche, Cimex lectularius; flea, Pulex irritans); head louse, Pediculus capitis, Pediculus corporis; crab louse, Pediculus pubis) |

| 60. Skin parasites (Achorion schoenleineii; Trichophyton tonsurans, Microsporum furfur, Microsporum andonini; micrococci of the smallpox vaccine; micrococci of erysipela) |

Abbreviation: HSJD, Hospital San Juan de Dios.

The plates are protected by sheets of thin, orange-tinted onion skin paper. References to other authors and books appear in the lower margins. Frequently cited is Clinical Lessons Concerning Skin Diseases (Lecciones clínicas sobre enfermedades de la piel) by Eugenè Guibout, a book published by the same journal-associated house that produced Pérez Ortiz's album. All the illustrations are of good quality, but outstanding is the 2-page spread depicting a man with anesthetic tuberculoid leprosy (Plates 38 and 39) (Fig. 3). The story of this case is a curious one. The patient came to Olavide in 1868, after having been treated by Pierre Louis Alphée Cazenave in Paris. He continued under Olavide's care until 1882, when he was referred to Pérez Ortiz. The patient died in 1883, 20 years after onset of disease.

ConclusionsAfter careful study of this volume, which its author did not choose to call an atlas, we believe it is an abridged, less costly copy of Olavide's magnificent Illustrated Atlas. This abridged version of the longer work, like the earlier one of Giné y Partagás (1880)4 and the later ones of De la Sota y Lastra (1886)6 and Oyarzábal (1911)7 served to spread knowledge of dermatology to many physicians and students of the time who could not have benefited from Olavide's atlas because of its high cost and gradual publication. This album is also of interest because many of its illustrations correspond to wax figures and moulages that can now be enjoyed in the collection of the Olavide Museum (Figs. 4 and 5).

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We thank Laboratory Meda for their collaboration with the Olavide Museum and for their gift of Pérez Ortiz's album to the museum's library.

Please cite this article as: Conde-Salazar L, Heras F, Maruri A, Aranda D. Álbum clínico de dermatología de Jerónimo Pérez Ortiz (1886). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:465–469.