An otherwise healthy 4-month-old girl who had been born full-term without birth trauma or prenatal or neonatal complications was brought to our practice because of a frontal tumor that had been present since birth. Physical examination revealed a deep frontal tumor of medium consistency that was mobile, unattached to the deeper layers, and without epidermal changes (Fig. 1). The rest of the examination was normal. No hypertelorism, nasal alterations, or dysmorphic facial features were observed.

A soft-tissue cranial ultrasound performed when the infant was 2 days old showed slight thickening of the subcutaneous tissue; this was also visible in a second ultrasound performed 2 months later. The diagnosis was congenital frontal lipoma.

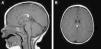

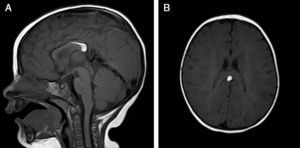

The patient was lost to follow-up but returned when she was 8 months old. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study showed an interhemispheric hyperintense mass on both T1- and T2-weighted sequences and a hypointense mass on fat-suppressed T2-weighted images. These findings were consistent with a lipoma (1.8cm×0.7cm×0.6cm on the anteroposterior, longitudinal, and transverse planes, respectively) associated with hypoplasia of the splenium of the corpus callosum. No tracts or other forms of communications were observed between the cerebral and frontal lipomas.

The patient was referred to a pediatric neurosurgeon, who decided to keep her in clinical follow-up. A second MRI study was performed 6 months later and no changes were observed (Fig. 2). The patient was also referred to the otolaryngologist to rule out Pai syndrome; the results of nasal fibroscopy were within normal limits. A year after diagnosis, the patient is still in follow-up, with excellent developmental milestones and no evidence of neurological complications.

Although lipomas are the most common type of benign soft-tissue tumors in adults, congenital presentation is rare.1 Furthermore, they are uncommon in children and account for just about 6% of all soft-tissue tumors in pediatric patients.1 Midline lipomas may be associated with central nervous system malformations, and in such cases, diverse radiologic studies and clinical follow-up are mandatory.2

Intracranial lipomas are also rare, accounting for just 0.06–0.46% of intracranial lesions.3 Most are located in the midline/interhemispheric region, most often in the corpus callosum. In about 50% of cases other disturbances, frequently associated with varying degrees of hypoplasia or agenesis of the corpus callosum, are identified in the surrounding nervous structures.4

Subcutaneous lipomas in association with intracranial lipomas are even rarer. The association could be related to the abnormal migration and proliferation of neural crest cells. Abnormal neural crest development results in many craniofacial malformations, known as neurocristopathies, including facial midline clefts.5–7 Intracranial and extracranial lipomas may be independent entities or connected through a frontal bone defect on the skull.2,6

Frontonasal dysplasia (FND) is a developmental alteration of the craniofacial region that comprises a spectrum of anomalies of the frontonasal area, including hypertelorism, nasal anomalies, and/or lip-palate cleft. The exact origin of FND is unknown and most cases are sporadic,7 although a mutation in the TGIF gene has been observed in familial cases of FND, which are very rare.8

Patients with FND may present with hypoplasia or agenesis of the corpus callosum and/or a corpus callosum lipoma.8 In a case series of patients with FND, all 8 patients had lipoma of the corpus callosum.9 Markers strongly associated with FND are falx cerebri calcifications and extracranial lipomas.8

Midline lipomas of the face and other craniofacial anomalies may be associated with intracranial malformations, including intracranial lipomas.

Brain MRI for the study of intracranial structures combined with clinical follow-up to monitor neurological changes seems to be the gold standard.2

Pai syndrome should be included in the differential diagnosis of FND-spectrum anomalies. This syndrome consists of pericallosal lipomas associated with facial abnormalities such as cutaneous polyps of the face and nasal mucosa, midline cleft, and midline pericallosal lipoma.10 As with our patient, a nasal fibroscopy should be performed to rule out this syndrome.

Although the majority of patients with intracranial lipomas are asymptomatic,10,11 a small number of patients may present neurological symptoms such as seizures, headache, and/or behavioral or psychosocial disorders.8 Routine neurosurgical treatment is not recommended because the surgical risk usually outweighs the benefits of the intervention.4 Surgical resolution of extracranial lipoma may provide cosmetic improvement and better quality of life.

The prognosis and psychomotor development of patients with intracranial lipomas is not clear, but based on data from patients with FND and Pai syndrome, their prognosis would appear to be favorable, with normal psychomotor development and no neurological impairment.8-10 Some patients with FND may have psychological alterations such as misanthropy and shyness.8,9

Lipomas are rare in children and are even rarer at birth. Facial midline lipomas should be assessed by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a dermatologist, neurosurgeons, an otolaryngologist, and radiologists. Neurologic images should be taken and in cases associated with corpus callosum or pericallosal lipoma, FND and Pai syndrome must be ruled out. Whether our patient represents an isolated case of frontal congenital lipoma with associated cerebral lipoma or an incomplete case within the spectrum of FND is currently unknown.