Work has already been done on validating the cross-cultural adaptation of the hair-specific Skindex-29 questionnaire (HSS-29) into Spanish. This questionnaire measures the impact of female-pattern hair loss on health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The aim of this study was to complete the validation process by testing the questionnaire’s sensitivity to change and assessing its correlation with the generic 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12).

Materials and methodsPatients who started treatment with a nutritional supplement that blocks the activity of 5 alpha-reductase were seen at 2 visits: a baseline visit and a follow-up visit at 6 months. At each visit, hair loss severity was assessed by both investigators and patients via the Sinclair scale, evaluation of hair condition, and administration of HSS-29 and SF-12.

ResultsIn total, 983 women with female-pattern hair loss participated in the study. The mean (SD) HSS-29 score decreased from 25.7 (18.7) at baseline to 19.3 (15.7) at follow-up and significant changes were also observed in the functioning, emotions, and symptoms domains. Changes in overall and subscale HSS-29 scores from baseline to follow-up were all significantly correlated with changes in SF-12 subscale scores. The Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from -0.1 to -0.4 and were all significant at P<.001.

ConclusionsThe Spanish version of HSS-29 is sensitive to change, as it detected changes in objective measurements of HRQoL. Correlations between HSS-29 and SF-12 scores were also observed.

Previamente se había iniciado el proceso metodológico para la validación transcultural al idioma español de la escala Hair Specific Skindex-29 (HSS-29), que mide el impacto de la alopecia androgénica femenina sobre la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS). Para finalizar el proceso, el objetivo del estudio fue completar la validación a través de la determinación de su sensibilidad al cambio y su correlación con una escala generalista de CVRS (SF-12).

Material y métodoSe establecieron dos visitas, una basal y tras seis meses de tratamiento con suplemento alimenticio con actividad inhibidora de la enzima 5-alfa reductasa. En cada visita, investigadores y pacientes valoraron la gravedad de la alopecia mediante la escala Sinclair, el estado de la apariencia del cabello, y se administraron las escalas HSS-29, SF-12.

ResultadosParticiparon 983 mujeres con alopecia androgénica. La media de puntuación en la escala HSS-29 cambió de 27,5±18,7 en la visita basal a 19,3±15,7 en la de seguimiento, y sus dimensiones funcional, emocional y sintomática también cambiaron significativamente. Tanto las diferencias entre basal y seguimiento en el índice HSS-29 global como en cada una de sus dimensiones se correlacionaron significativamente con las diferencias encontradas en las dimensiones de SF-12. Los coeficientes de correlación de Pearson oscilaron entre -0,1 y -0,4 y en todos los casos el grado de significación fue p<0,001.

ConclusionesLa versión en español de la escala HSS-29 posee sensibilidad, es decir detecta cambios relacionados con la calidad de vida cuando las condiciones objetivas varían. Igualmente, se observó una correlación entre las escalas HSS-29 y SF-12.

During the years 2016 and 2018, a Spanish group carried out a cross-cultural validation of the Spanish-language version of the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 (HSS-29) scale, which was based on the Skindex-29 scale1 for measuring the impact of female androgenetic alopecia on health-related quality of life (HRQOL).

This result was an adapted functional Spanish-language version of the HSS-29 scale. The process was described, and the results were published in Actas Dermosifiliográficas in 2018.2

In order to finalize the validation process and complete all of its phases, it was decided to evaluate sensitivity to change and its correlation with the generic 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12).3

Material and MethodsPopulationThe study sample included 983 women from 101 dermatology clinics in the different Spanish autonomous communities. The women consulted for female androgenetic alopecia and participated voluntarily after receiving appropriate information. They started treatment with dietary supplements containing 5-α-reductase enzyme inhibitor and had not received treatment with supplements in the previous 3 months.

InstrumentsQuality of life was evaluated using HSS-29 (Appendix B1. Additional Material) and SF-12 (Appendix B2. Additional Material). The HSS-29 questionnaire is a self-administered tool that makes it possible to evaluate HRQOL in patients with alopecia. It was based on the Skindex-29 scale and is composed of 29 items distributed over 3dimensions or domains: symptoms (7items), function (12items), and emotions (10items). The questionnaire takes a mean of 5minutes to complete, and each item is answered based on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (all the time). The dimensions are scored by transforming the sum of all the responses to a linear scale ranging from 0 (no impact) to 100 (maximum impact).

The SF-12 questionnaire contains 12items covering 8 HRQOL domains: physical dimension, mental dimension, physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, role-emotional, social functioning, and mental health. Reference guidelines are available for the Spanish version of SF-12 (version 2).4

Furthermore, the patient and the clinician were asked their opinion on the volume, density, and texture of the hair.

DesignPatients attended 2 visits, one at baseline and the other after 6months of treatment. At the baseline visit, patients initiated treatment with 5-α-reductase enzyme inhibitor dietary supplements, which they continued to take for 6months. They completed both questionnaires at each visit, and the investigators evaluated the severity of alopecia using the Sinclair scale. Both the patient and the clinician evaluated the volume, density, and texture of the hair as better, worse, or no change.

The project for cross-cultural adaptation to Spanish began in 2016, according to the protocol approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital 12 de Octubre on December 20 (No. 16/392). The second phase was carried out between January and October 2018.

Data AnalysisFirst, a descriptive analysis of the data was performed using a frequency table for nominal variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables. Data for continuous variables were presented with their 95%CI.

Comparisons between groups and quantitative variables were made using the t test (2groups) or 1-way analysis of variance (≥3 groups). If either of these tests could not be applied, the Mann-Whitney test (2groups) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (≥3 groups) was used. Where necessary, tests for paired data were applied. Continuous variables were compared using the Fisher correlation coefficient in the case of absolutely continuous variables or the Spearman test in the case of those that were not. All calculations were made using SAS Version 9.4.

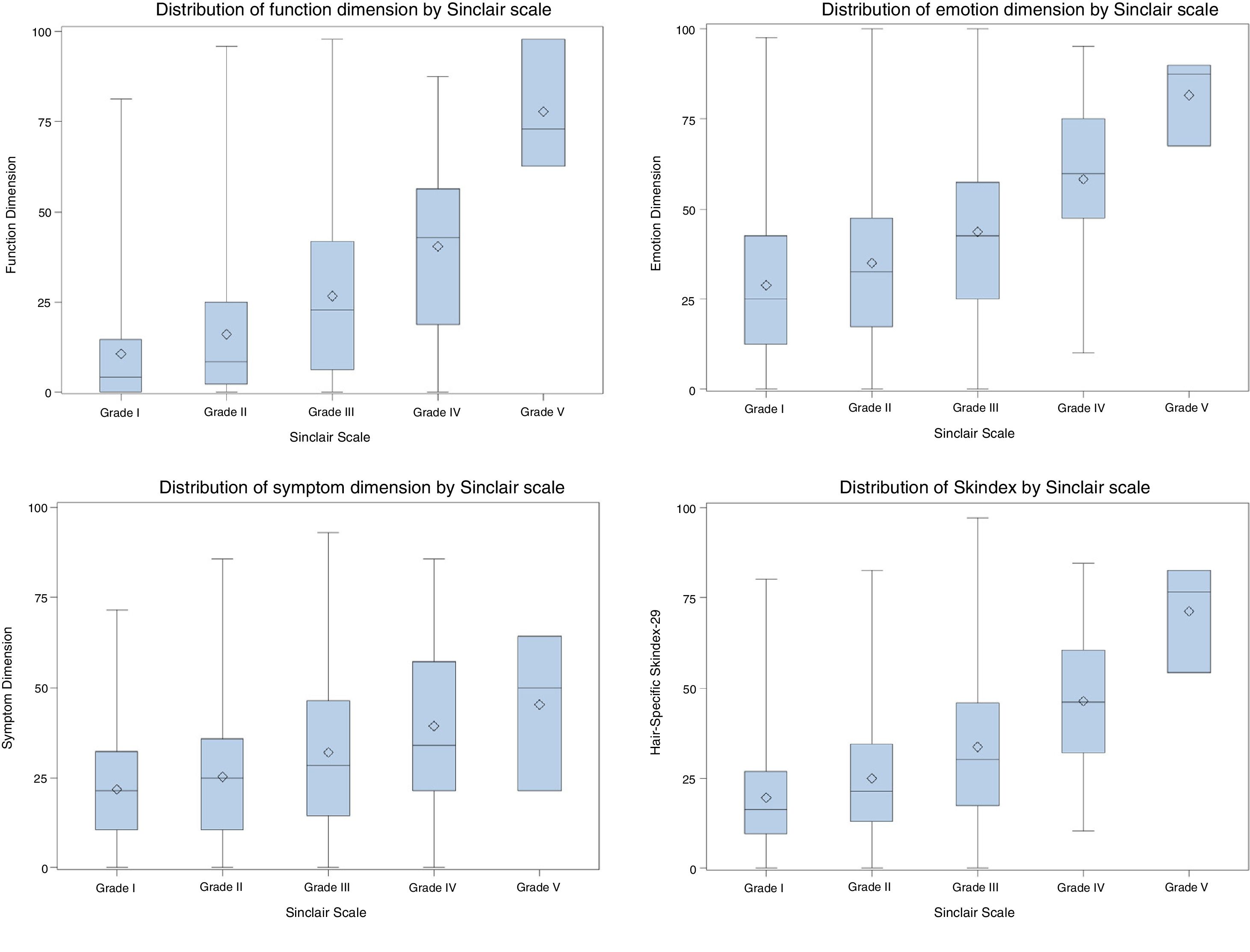

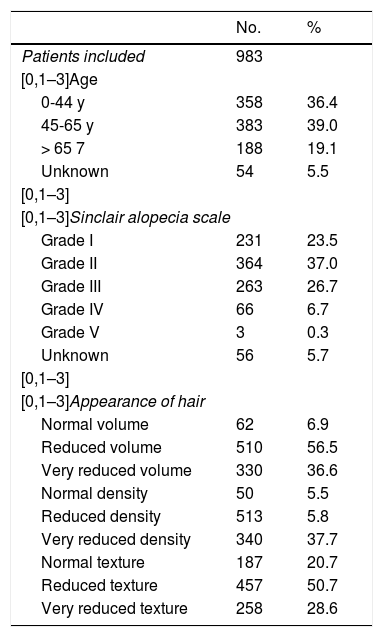

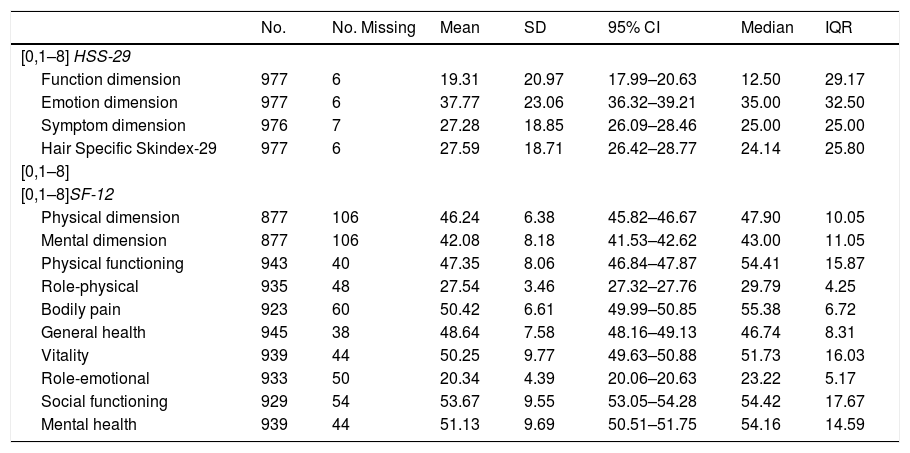

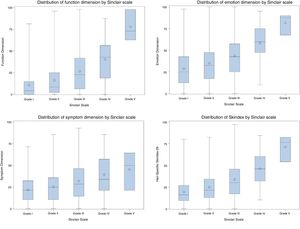

ResultsBaseline VisitTable 1 shows the characteristics of the patients included in the study. The study population comprised 983 women with a mean age of 50 (16.3) years and mainly (83.6%) grade 1–3 alopecia according to the Sinclair scale. Table 2 shows the total score and the score by dimensions on the HSS-29 scale. The grade of alopecia is shown in Fig. 1. Emotion was the most affected domain, with a mean score of 37.7 (95%CI, 36.3–39.2); the score was lower in the symptom and function domains, with a mean of 27.2 (95% CI, 26.0–28.4) and 19.3 (95%CI, 17.9–20.6), respectively. We found that involvement was more pronounced as alopecia became more severe, both in the overall score and in the various dimensions. No significant differences were detected for age group with respect to the score on the scale as a whole or in its individual dimensions. The baseline SF-12 score is also shown in Table 2. The domain with the greatest impact on quality of life was role-emotional, with a mean score of 20.3 (95%CI, 20.0–20.6). As in the HSS-29, involvement was more pronounced as alopecia became worse in all the scores recorded for the SF-12.

Patient Characteristics by Age, Sinclair Grade, and Appearance of Hair at Baseline.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients included | 983 | |

| [0,1–3]Age | ||

| 0-44 y | 358 | 36.4 |

| 45-65 y | 383 | 39.0 |

| > 65 7 | 188 | 19.1 |

| Unknown | 54 | 5.5 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Sinclair alopecia scale | ||

| Grade I | 231 | 23.5 |

| Grade II | 364 | 37.0 |

| Grade III | 263 | 26.7 |

| Grade IV | 66 | 6.7 |

| Grade V | 3 | 0.3 |

| Unknown | 56 | 5.7 |

| [0,1–3] | ||

| [0,1–3]Appearance of hair | ||

| Normal volume | 62 | 6.9 |

| Reduced volume | 510 | 56.5 |

| Very reduced volume | 330 | 36.6 |

| Normal density | 50 | 5.5 |

| Reduced density | 513 | 5.8 |

| Very reduced density | 340 | 37.7 |

| Normal texture | 187 | 20.7 |

| Reduced texture | 457 | 50.7 |

| Very reduced texture | 258 | 28.6 |

Scores on the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 (HSS-29) and 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) Scales: Baseline Visit.

| No. | No. Missing | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Median | IQR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–8] HSS-29 | |||||||

| Function dimension | 977 | 6 | 19.31 | 20.97 | 17.99–20.63 | 12.50 | 29.17 |

| Emotion dimension | 977 | 6 | 37.77 | 23.06 | 36.32–39.21 | 35.00 | 32.50 |

| Symptom dimension | 976 | 7 | 27.28 | 18.85 | 26.09–28.46 | 25.00 | 25.00 |

| Hair Specific Skindex-29 | 977 | 6 | 27.59 | 18.71 | 26.42–28.77 | 24.14 | 25.80 |

| [0,1–8] | |||||||

| [0,1–8]SF-12 | |||||||

| Physical dimension | 877 | 106 | 46.24 | 6.38 | 45.82–46.67 | 47.90 | 10.05 |

| Mental dimension | 877 | 106 | 42.08 | 8.18 | 41.53–42.62 | 43.00 | 11.05 |

| Physical functioning | 943 | 40 | 47.35 | 8.06 | 46.84–47.87 | 54.41 | 15.87 |

| Role-physical | 935 | 48 | 27.54 | 3.46 | 27.32–27.76 | 29.79 | 4.25 |

| Bodily pain | 923 | 60 | 50.42 | 6.61 | 49.99–50.85 | 55.38 | 6.72 |

| General health | 945 | 38 | 48.64 | 7.58 | 48.16–49.13 | 46.74 | 8.31 |

| Vitality | 939 | 44 | 50.25 | 9.77 | 49.63–50.88 | 51.73 | 16.03 |

| Role-emotional | 933 | 50 | 20.34 | 4.39 | 20.06–20.63 | 23.22 | 5.17 |

| Social functioning | 929 | 54 | 53.67 | 9.55 | 53.05–54.28 | 54.42 | 17.67 |

| Mental health | 939 | 44 | 51.13 | 9.69 | 50.51–51.75 | 54.16 | 14.59 |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

The score for the dimensions of the HSS-29 scale ranges from 0 (no impact) to 100 (maximum impact). Each item on the SF-12 scale evaluates different aspects on a scale of 0 (no quality of life) to 100 (maximum quality of life).

Hair-Specific Skindex-29 and severity of alopecia.

Total score and score by dimension according to the severity of alopecia (Sinclair scale) at the baseline visit. Involvement in the function, emotion, and symptom dimensions of the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 scale and overall involvement increase with the severity of alopecia.

t test/ANOVA between the score on the function dimension and grade of severity: P<.001. t test/ANOVA between the emotion dimension and grade of severity: P<.001. t test/ANOVA between the symptom dimension and grade of severity: P<.001. t test/ANOVA between the overall score and grade of severity: P<.001. ANOVA indicates analysis of variance.

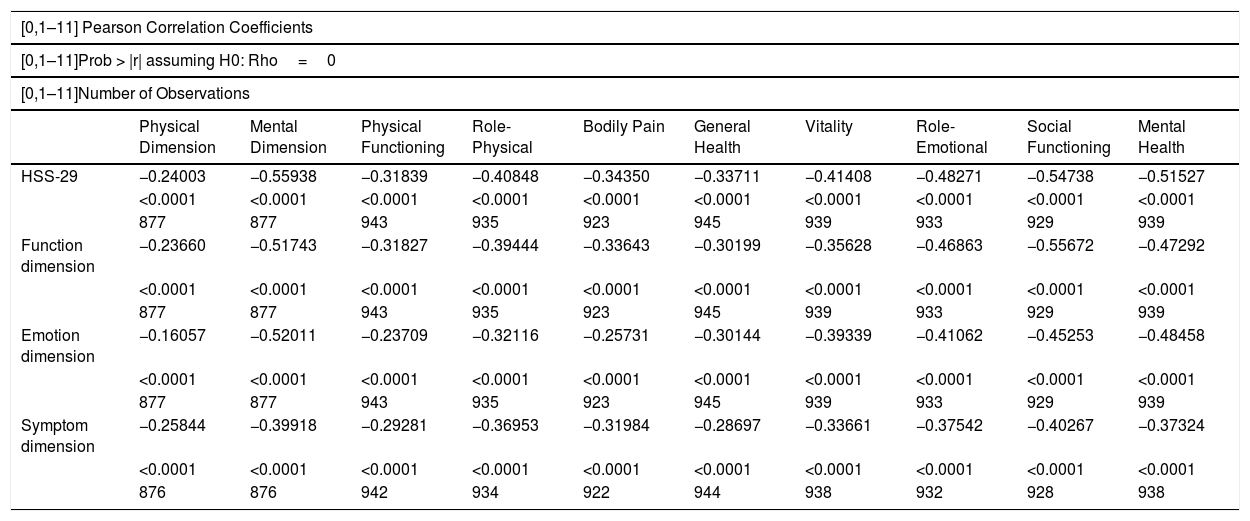

The correlation between both scales at baseline is presented in Table 3. All of the correlations studied using Pearson coefficients were negative and statistically significant (P< .001). A higher score in the HSS-29 and all its subdimensions (function, emotion, and symptoms) was associated with a lower score, i.e., reduced HRQOL, in all of the dimensions of the SF-12 scale. Similarly, the mean scores on the SF-12 decreased as severity in the HSS-29 increased in its classified form. When the study population was stratified by age group and severity of alopecia, we observed the same negative correlation in all the groups, except in patients with grade 5 alopecia. No analysis was performed for this subgroup, since it only included 3women.

Coefficients for the Correlation Between the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 (HSS-29) and 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey at Baseline: Pearson Coefficients for the Correlation Between Both Instruments.

| [0,1–11] Pearson Correlation Coefficients | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–11]Prob > |r| assuming H0: Rho=0 | ||||||||||

| [0,1–11]Number of Observations | ||||||||||

| Physical Dimension | Mental Dimension | Physical Functioning | Role-Physical | Bodily Pain | General Health | Vitality | Role-Emotional | Social Functioning | Mental Health | |

| HSS-29 | −0.24003 | −0.55938 | −0.31839 | −0.40848 | −0.34350 | −0.33711 | −0.41408 | −0.48271 | −0.54738 | −0.51527 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 877 | 877 | 943 | 935 | 923 | 945 | 939 | 933 | 929 | 939 | |

| Function dimension | −0.23660 | −0.51743 | −0.31827 | −0.39444 | −0.33643 | −0.30199 | −0.35628 | −0.46863 | −0.55672 | −0.47292 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 877 | 877 | 943 | 935 | 923 | 945 | 939 | 933 | 929 | 939 | |

| Emotion dimension | −0.16057 | −0.52011 | −0.23709 | −0.32116 | −0.25731 | −0.30144 | −0.39339 | −0.41062 | −0.45253 | −0.48458 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 877 | 877 | 943 | 935 | 923 | 945 | 939 | 933 | 929 | 939 | |

| Symptom dimension | −0.25844 | −0.39918 | −0.29281 | −0.36953 | −0.31984 | −0.28697 | −0.33661 | −0.37542 | −0.40267 | −0.37324 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 876 | 876 | 942 | 934 | 922 | 944 | 938 | 932 | 928 | 938 | |

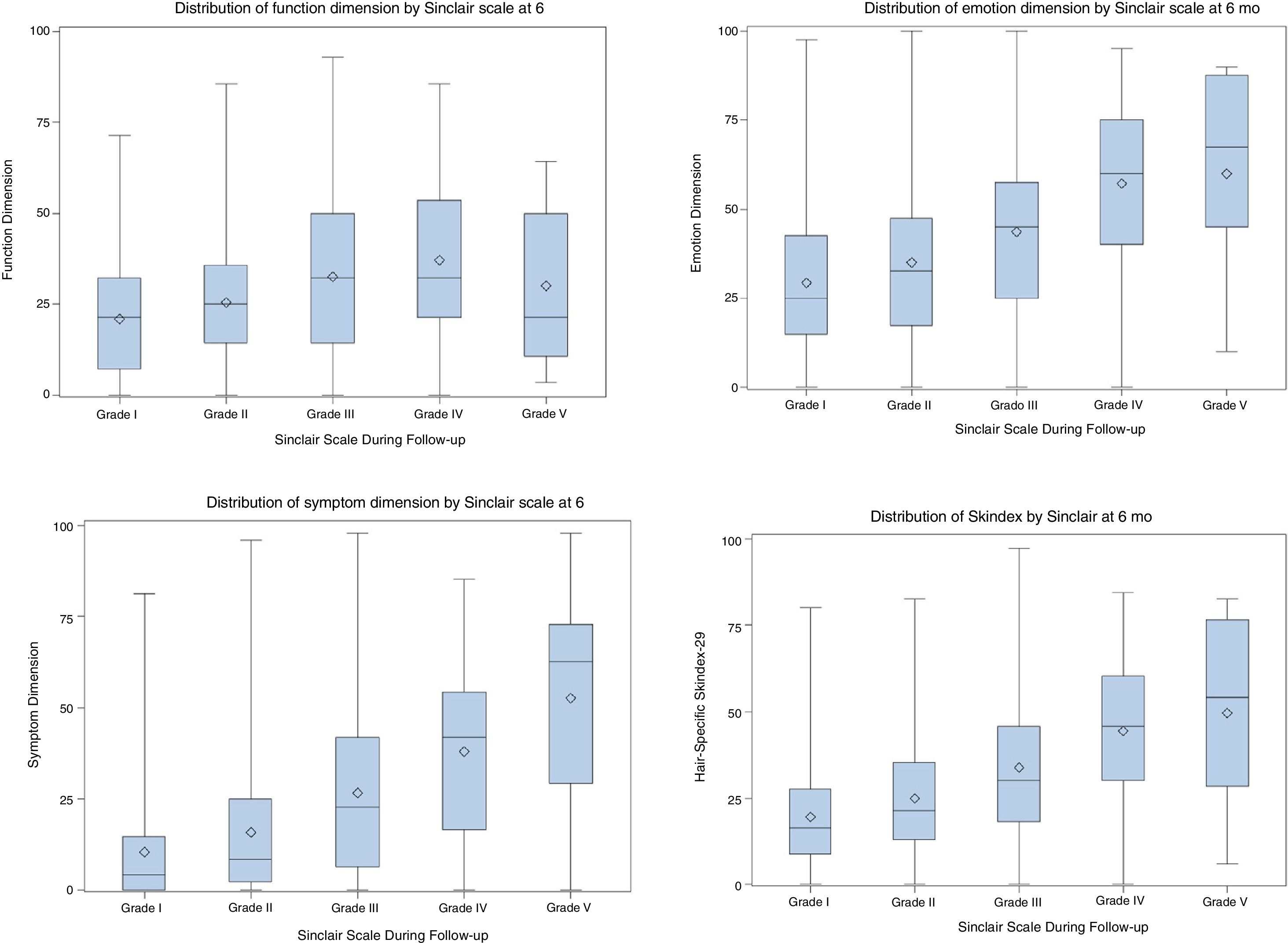

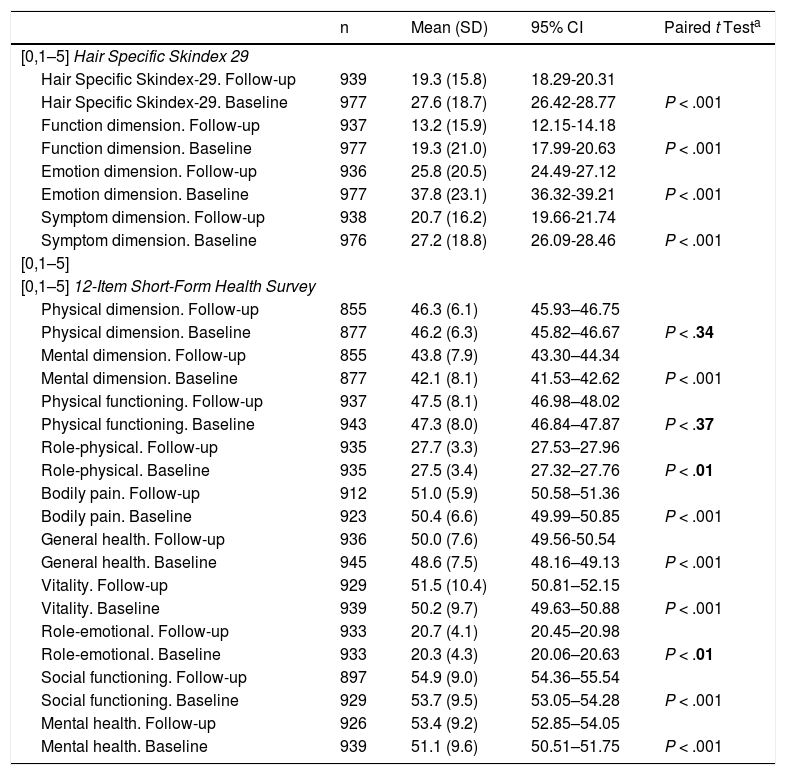

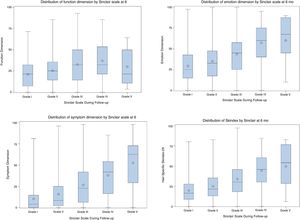

Of the 983 patients included in the initial project, 967 (98.3%) were evaluated at 6months. Compared with the baseline score, the global score on the HSS-29 scale at 6months decreased overall and in the scores for the individual dimensions, in which the differences were statistically significant (Table 4). The mean score on the overall scale fell from 27.5(18.7) at baseline to 19.3(15.7) at the follow-up visit. Significant changes were also observed for the function, emotion, and symptom dimensions, from 19.3(2.0) to 13.1(15.8), from 37.7(23.0) to 25.8(20.5), and from 27.2(18.8) to 20.7(16.2), respectively. Fig. 2 shows the differences between the 2 visits according to the grade of alopecia. All of the differences evaluated were statistically significant with respect to the grade of alopecia.

Scores on the Hair Specific Skindex 29 and 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey Scales at Baseline and During Follow-up.

| n | Mean (SD) | 95% CI | Paired t Testa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5] Hair Specific Skindex 29 | ||||

| Hair Specific Skindex-29. Follow-up | 939 | 19.3 (15.8) | 18.29-20.31 | |

| Hair Specific Skindex-29. Baseline | 977 | 27.6 (18.7) | 26.42-28.77 | P < .001 |

| Function dimension. Follow-up | 937 | 13.2 (15.9) | 12.15-14.18 | |

| Function dimension. Baseline | 977 | 19.3 (21.0) | 17.99-20.63 | P < .001 |

| Emotion dimension. Follow-up | 936 | 25.8 (20.5) | 24.49-27.12 | |

| Emotion dimension. Baseline | 977 | 37.8 (23.1) | 36.32-39.21 | P < .001 |

| Symptom dimension. Follow-up | 938 | 20.7 (16.2) | 19.66-21.74 | |

| Symptom dimension. Baseline | 976 | 27.2 (18.8) | 26.09-28.46 | P < .001 |

| [0,1–5] | ||||

| [0,1–5] 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey | ||||

| Physical dimension. Follow-up | 855 | 46.3 (6.1) | 45.93–46.75 | |

| Physical dimension. Baseline | 877 | 46.2 (6.3) | 45.82–46.67 | P < .34 |

| Mental dimension. Follow-up | 855 | 43.8 (7.9) | 43.30–44.34 | |

| Mental dimension. Baseline | 877 | 42.1 (8.1) | 41.53–42.62 | P < .001 |

| Physical functioning. Follow-up | 937 | 47.5 (8.1) | 46.98–48.02 | |

| Physical functioning. Baseline | 943 | 47.3 (8.0) | 46.84–47.87 | P < .37 |

| Role-physical. Follow-up | 935 | 27.7 (3.3) | 27.53–27.96 | |

| Role-physical. Baseline | 935 | 27.5 (3.4) | 27.32–27.76 | P < .01 |

| Bodily pain. Follow-up | 912 | 51.0 (5.9) | 50.58–51.36 | |

| Bodily pain. Baseline | 923 | 50.4 (6.6) | 49.99–50.85 | P < .001 |

| General health. Follow-up | 936 | 50.0 (7.6) | 49.56-50.54 | |

| General health. Baseline | 945 | 48.6 (7.5) | 48.16–49.13 | P < .001 |

| Vitality. Follow-up | 929 | 51.5 (10.4) | 50.81–52.15 | |

| Vitality. Baseline | 939 | 50.2 (9.7) | 49.63–50.88 | P < .001 |

| Role-emotional. Follow-up | 933 | 20.7 (4.1) | 20.45–20.98 | |

| Role-emotional. Baseline | 933 | 20.3 (4.3) | 20.06–20.63 | P < .01 |

| Social functioning. Follow-up | 897 | 54.9 (9.0) | 54.36–55.54 | |

| Social functioning. Baseline | 929 | 53.7 (9.5) | 53.05–54.28 | P < .001 |

| Mental health. Follow-up | 926 | 53.4 (9.2) | 52.85–54.05 | |

| Mental health. Baseline | 939 | 51.1 (9.6) | 50.51–51.75 | P < .001 |

Hair Specific Skindex-29.: Differences in score between the first and second visit for each grade of alopecia. The presence of negative differences indicates a reduced impact on quality of life at the second visit.

Difference at 6months from baseline in the function dimension: t test/ANOVA P<.001. Difference at 6months from baseline in the emotion dimension: t test/ANOVA P<.01478. Difference at 6months from baseline in the symptom dimension: t test/ANOVA P<.0009. Difference at 6months from baseline in the Hair Specific Skindex-29 global: t test/ANOVA P<.0001.

Depending on the severity of alopecia, differences were observed in the score on the HSS-29 scale between the first and second visits, with an improvement in involvement of quality of life (i.e., scores <20 in the HSS-29 scale in all its domains and for all grades of alopecia). Fig. 2 shows the differences between the first and second evaluation.

A statistically significant increase in the SF-12 scores was observed in the dimensions role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, role-emotional, social functioning, and mental health at 6months, whereas the change in the physical dimension and physical functioning was not significant (Table 4).

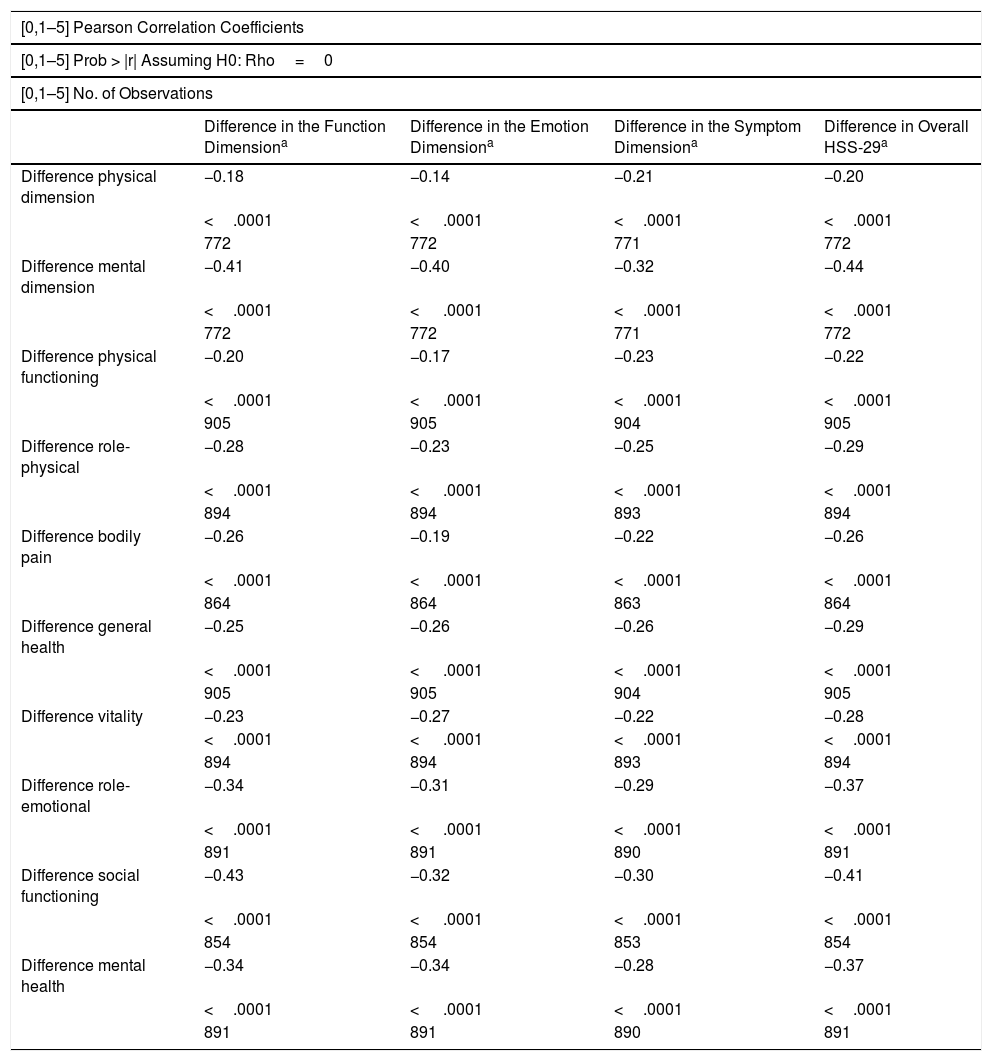

Sensitivity to ChangeIn order to evaluate sensitivity to change, we calculated the differences between the scores at 6months and the baseline scores for all the dimensions on the HSS-29 and SF-12 scales and assessed the evaluations of the appearance of the patients’ hair. We then determined whether these differences were correlated or not, that is, whether one changed with the other. The analysis was performed for the whole study population and by age group and grade of alopecia.

Table 5 shows the correlation for the differences between the scales, that is, whether one changed with the other. We observed that the differences between baseline and follow-up both for the overall HSS-29 index and for each of its dimensions were significantly correlated with the differences found for the dimensions of the SF-12. The Pearson correlation coefficients ranged between −0.1 and −0.4, and statistical significance in all cases was P<.001. The scatterplots for the correlation of differences are shown in Appendix BAnnex 3 (Additional material).

Sensitivity to Change: Correlation Between Hair-Specific Skindex 29 (HSS-29) and 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey.

| [0,1–5] Pearson Correlation Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5] Prob > |r| Assuming H0: Rho=0 | ||||

| [0,1–5] No. of Observations | ||||

| Difference in the Function Dimensiona | Difference in the Emotion Dimensiona | Difference in the Symptom Dimensiona | Difference in Overall HSS-29a | |

| Difference physical dimension | −0.18 | −0.14 | −0.21 | −0.20 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 772 | 772 | 771 | 772 | |

| Difference mental dimension | −0.41 | −0.40 | −0.32 | −0.44 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 772 | 772 | 771 | 772 | |

| Difference physical functioning | −0.20 | −0.17 | −0.23 | −0.22 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 905 | 905 | 904 | 905 | |

| Difference role-physical | −0.28 | −0.23 | −0.25 | −0.29 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 894 | 894 | 893 | 894 | |

| Difference bodily pain | −0.26 | −0.19 | −0.22 | −0.26 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 864 | 864 | 863 | 864 | |

| Difference general health | −0.25 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.29 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 905 | 905 | 904 | 905 | |

| Difference vitality | −0.23 | −0.27 | −0.22 | −0.28 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 894 | 894 | 893 | 894 | |

| Difference role-emotional | −0.34 | −0.31 | −0.29 | −0.37 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 891 | 891 | 890 | 891 | |

| Difference social functioning | −0.43 | −0.32 | −0.30 | −0.41 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 854 | 854 | 853 | 854 | |

| Difference mental health | −0.34 | −0.34 | −0.28 | −0.37 |

| <.0001 | < .0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | |

| 891 | 891 | 890 | 891 | |

Pearson correlation coefficients between the HSS-29 and SF-12 scales, evaluated based on the differences in the score between the baseline visit and the follow-up visit for each item studied.

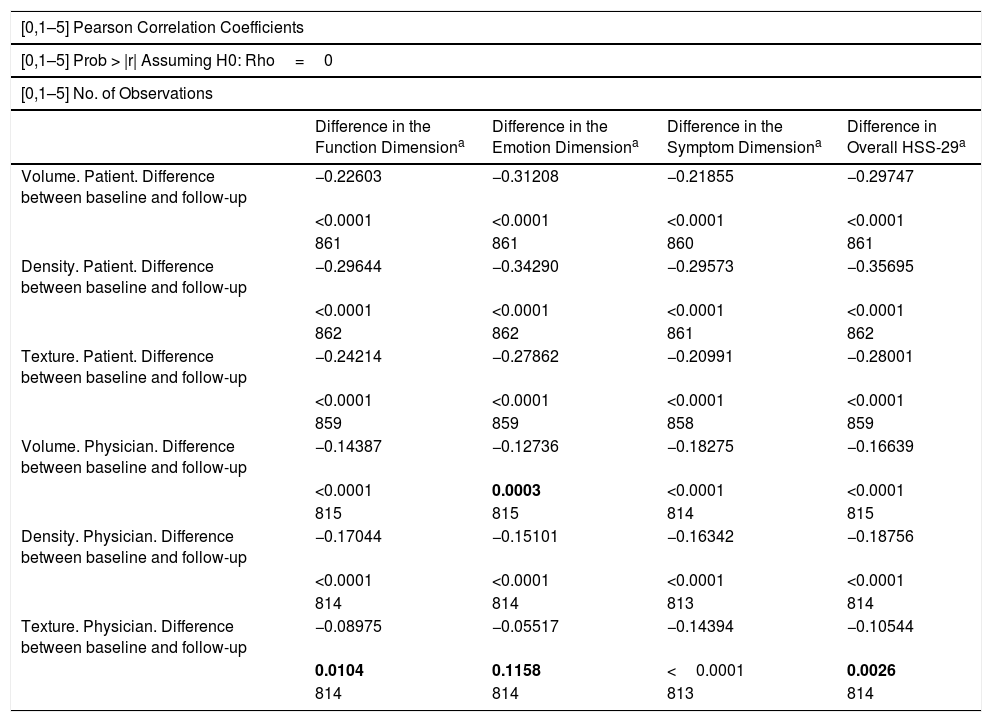

Lastly, Table 6 shows the differences between the appearance of the patients’ hair and the HSS-29 score. All of the correlations examined were statistically significant, except for texture as assessed by the clinician compared with progress in the emotion dimension. As the indices for the evaluation of the hair worsened, the HSS-29 score decreased. Both the physician’s and the patient’s evaluation revealed an improvement in the appearance of the hair in the categories volume, density, and texture. For a score of 1–3 (1 normal, 3 very diminished), the means perceived by the patients decreased from 2.3 (0.5) to 1.8 (0.6), from 2.3(0.5) to 1.8(0.6), and from 2.0(0.7) to 1.5(0.6) in volume, density, and texture, respectively. The means perceived by the physician decreased from 2.0(0.5) to 1.5(0.6), from 2.1(0.5) to 1.7(0.5), and from 1.8(0.6) to 1.3(0.5). All of the results were significant. In approximate terms, the higher the grade of alopecia, the greater the improvement, although data for grade5 alopecia were not taken into consideration because there were only 3 patients in this group. No statistically significant differences in patient progress were detected by age group.

Sensitivity to Change. Correlation Between Hair Specific Skindex 29 and the Evaluation of the Appearance of the Hair.

| [0,1–5] Pearson Correlation Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0,1–5] Prob > |r| Assuming H0: Rho=0 | ||||

| [0,1–5] No. of Observations | ||||

| Difference in the Function Dimensiona | Difference in the Emotion Dimensiona | Difference in the Symptom Dimensiona | Difference in Overall HSS-29a | |

| Volume. Patient. Difference between baseline and follow-up | −0.22603 | −0.31208 | −0.21855 | −0.29747 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 861 | 861 | 860 | 861 | |

| Density. Patient. Difference between baseline and follow-up | −0.29644 | −0.34290 | −0.29573 | −0.35695 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 862 | 862 | 861 | 862 | |

| Texture. Patient. Difference between baseline and follow-up | −0.24214 | −0.27862 | −0.20991 | −0.28001 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 859 | 859 | 858 | 859 | |

| Volume. Physician. Difference between baseline and follow-up | −0.14387 | −0.12736 | −0.18275 | −0.16639 |

| <0.0001 | 0.0003 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 815 | 815 | 814 | 815 | |

| Density. Physician. Difference between baseline and follow-up | −0.17044 | −0.15101 | −0.16342 | −0.18756 |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| 814 | 814 | 813 | 814 | |

| Texture. Physician. Difference between baseline and follow-up | −0.08975 | −0.05517 | −0.14394 | −0.10544 |

| 0.0104 | 0.1158 | <0.0001 | 0.0026 | |

| 814 | 814 | 813 | 814 | |

Correlation between the differences observed by the physician and the patient in density, volume, and texture of the patient’s hair at the baseline and follow-up visits and differences in the Hair-Specific Skindex-29 score between the baseline and follow-up visits.

Evaluation of the psychometric properties of an instrument is essential when determining quality of the measurements it generates. When evaluating the accuracy of an instrument, the key characteristics of a measurement are reliability, validity, sensitivity, and feasibility. Reliability refers to the ability to measure a variable in a constant manner; validity refers to whether or not the instrument measures what it is intended to measure. Not all reliable instruments are valid, since an instrument may be reliable because it measures the variables in a constant manner but invalid if it does not appropriately measure the phenomenon it is intended to measure.5 The validity of an instrument also depends on its sensitivity and feasibility. Sensitivity shows the ability to detect changes in items or subjects evaluated after an intervention.6 It is associated with differences in the scores of a subject who has improved or worsened and scores that remained unchanged.7 Lastly, feasibility evaluates whether the questionnaire can actually be used in the field it is intended to be used in.

Both generic HRQOL questionnaires and dermatology-specific questionnaires have been used for the study of quality of life in many skin diseases.8 In patients with alopecia, Williamson et al.9 used an adapted version of the Dermatology Life Quality Index, although this is not specific for measuring the effect of alopecia in women, which is probably more intense than in men. In the case of women with alopecia, Schmidt et al.10 applied the Hairdex scale (not available in Spanish), and, in Finland, Hirsso et al.11 used the generic RAND36 scale. The Symptom Checklist-90-R, which is specific to psychopathology, has also been used as a complementary approach.12

HSS-29 is the only specific instrument available in Spanish for evaluation of HRQOL in women with alopecia2. In the present project, we completed the validation of HSS-29. Our data show that it is sensitive to change, that is, the score changes as the grade of female alopecia decreases. Similarly, the values obtained in the HSS-29 are significantly associated with the aspects evaluated using a generic HRQOL scale.

The correlations between the scales were statistically significant at both the baseline visit and at the follow-up visit. Quality of life in all the dimensions of SF-12 worsened as the score on the HSS-29 and its subdimensions (function, emotions, symptoms) increased. Thus, the correlations are negative, because in the case of HSS-29, the score for each dimension is obtained by transforming the sum of all the responses on a linear scale of 0 (no impact on quality of life) to 100 (maximum impact), whereas on the SF-12, a higher score indicates better quality of life. Involvement in the emotion domain of the HSS-29, with a mean score of 37.7, was higher than in the symptom and function domains. This is consistent with the SF-12, where role-emotional was the dimension most affected by alopecia. The instrument seems to be very sensitive, since, compared with baseline, the HSS-29 score at 6months decreased both overall and in the individual dimensions, for which the differences were statistically significant. This aspect is relevant, both in the validation of the test itself, since sensitivity is an important psychometric property, and in the evaluation of the efficacy of therapy.

Women with female androgenetic alopecia have a more negative perception of their health and psychosocial situation than women who do not experience hair abnormalities.10,13,14 The condition may even be associated with depressive symptoms.15 Van der Donk et al.16 reported that 50% of women with alopecia had social problems and that 80% felt that their daily life was affected to some extent. In a study performed in Finnish women, Hirsso et al.11 suggested that alopecia may even be associated with physical symptoms. We found that the effect of female androgenetic alopecia on HRQOL was considerable, particularly in the emotion domain: the more severe the alopecia, the more the patient was affected, both overall and in the individual dimensions. This impact is reflected in data obtained using the HSS-29 and the SF-12, although the former was more sensitive to change. The SF-12 focuses on physical limitations and emotional status independently of the cause, and it may be for this reason that the HSS-29, which focuses more on the impact of alopecia, is more sensitive to changes in the condition of the hair.

The validation project is particularly interesting because of its sample size (983 women), which is larger than that of other studies on quality of life in dermatology. In addition, the number of losses was relatively small (12.1%). Similarly, questionnaires on quality of life translate concepts to numerical scales, although this measurement could be completed with a qualitative evaluation. A growing number of researchers now use such an approach.17

ConclusionsOur data show that the Spanish version of HSS-29 is a useful tool for evaluating quality of life in women with female androgenetic alopecia and that it is considerably sensitive, i.e., it is significantly able to detect changes in quality of life when objective conditions vary. We also observed a correlation between the HSS-29 and SF-12 scales, both at the baseline visit and during follow-up. This same correlation was observed for differences in score between HSS-29 and differences in the evaluation of the appearance of the hair both by physicians and by patients.

FundingThe project for the adaptation of the Spanish version of Hair Specific Skindex-29 was supported by a research grant from Laboratorio Reig Jofre.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Members of the Hair Specific Skindex-29 Validation Group

Juan Ferrando Barbera, Agustín Buendía Eisman, Aurora Guerra Tapia, Ana Garayalde Perurena, Yolanda Juárez Casado, Dolores Otero Tejero, David Carlos Camacho Nuñez, Héctor Juan Morales Moreno, Priti Mohan Melwani, Anna Vilanova Mateu, Loida Galvany Rossell, Paloma del Valle Calderón Andrés, Rosa Izu Belloso, Marta Ballestero Diez, Ana Isabel Bernal Ruiz, Miren Urcelay Mendiaraz, Manuel Almagro Sánchez, Antoni Mas Ferra, Miguel Servera Llaneras, Laura Asumendi Redondo, María Rueda Gómez-Calcerrada, Mercedes Hospital Gil, Cristina Pérez Mortet, María Loreto Crego Diéguez, Néstor Santana Molina, Margarita Puerto Castrillón, Rafael Aguayo Ortiz, Esperanza Martínez Ruiz, Antonio Javier González Rodríguez, Eugenia Agut Busquet, Mireia Sabat Santandreu, Walter Espinosa Delgado, Roberto Marengo Otero, Mercedes Pico Valimaña, Isabel Nieto Montesinos, Laura Cuesta Montero, Alfredo Daniel Agullo Pérez, Teresa Ojeda Vila, Carolina Vila Sava, Manuel Peña Blanco, Eva Balbín Carrero, Manuel Claros Romero, Verónica Díaz Fernández, Marina Rodríguez Martin, Blas Alexis Gómez Dorado, María Carmen Goday Maso, Servando Eugenio Marron Moya, María del Carmen Vázquez Bayo, María Teresa Arguisjuela Hermida, Kristyna Vorlicka, Guillermo Enrique Solano López Morel, Silvia Gallego Álvarez, Olga González Valle, María Concepción Fuente Lázaro, Antonia Reyes Ramírez, Jesús Manuel Borbujo Martínez, María Teresa de Pedro Herrero, Teresa Efigenia Lázaro Cantalejo, Rosa Ballester Sánchez, Patricia García Morras, Sergio Hernández Ostiz, Rosa María Ortega del Olmo, Salvador Arias Santiago, Amaia de Mariscal Polo, Clara Martín Callizo, Nayra Patricia Merino de Paz, Carmen Ruiz Doménech, Juan Manuel Verdeguer Miralles, Fernando Javier Allegue Gallego, Francisco José de León Marrero, Marisa Cáceres Cwiek, Marta Lamoca Martin, Luis Miguel Valladares Narganes, José Carlos San Martin Muñiz, María Covadonga Martínez González, Manuel Sánchez Regaña, Maite Robles Portillo, Vicente Aneri Mas, Javier García Navarro, María Carmen Diaz Sarrio, José Luis García Fernández, Yolanda Carames Varela, Miriam Sidro Sarto, María Teresa Martín-Urda Díez-Canseco, Basilio Narváez Moreno, Mario León Gil, Marina del Hoyo González, Rebeca Sonali Lax, María Teresa Fernández, María Dolores García Plata, Elena González Guerra, José Manuel Pazos Campos, Luis Pastor Llord, Susana del Canto González, Antonio Martorell Calatayud, Vicente Manuel Leis Dosil, María Elisa García, Guadalupe Fernández Buezo, Emili Masferrer Niubó, Carmen Martínez Peinado, Josep Pujol Montcusí.

Los miembros del grupo de validación Hair Specific Skindex-29 se indican en el Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Guerra-Tapia A, et al. Fase final de la validación transcultural al espa˜nol de la escala Hair Specific Skindex-29: sensibilidad al cambio y correlación con la escala SF-12. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:819–829.