The Cantigas of Holy Mary are a large collection of 420 poems to be sung, prefaced by 2 prologues. The poems, attributed to King Alfonso X of Castile, are dedicated to the Virgin and praise her miracles.

Alfonso X, known as “the Learned” or “the Wise,” was born in Toledo in 1221 and died in Seville in 1284 after playing an important part in the events of his time. Following in the footsteps of his father, Fernando III, Alfonso was successful in his energetic pursuit of war against the Moorish kingdoms of the Iberian peninsula. He sponsored the production of a vast body of writing on history, science and law as well as many literary works, bringing together a remarkable contingent of Latin, Jewish and Islamic musicians and intellectuals. He promoted the use of Castilian for prose, but for lyrical expression he favored Galician-Portuguese, the educated vernacular language of the court at that time. The king was tormented by family infighting and health problems, which have engendered lively debate. Alfonso's great aspiration to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor was never realized, but his intense, productive life speaks of a restless, intelligent and sensitive man who also had to cope with disease and hardship.

The Cantigas of Holy Mary are certainly Alfonso's greatest artistic legacy. This immense corpus of music, poetry, and illustration is the largest repository of songs surviving in a vernacular European language with the musical notation intact. They tell us about daily life in Alfonso's time, in particular revealing how disease, with its causes and treatments, was perceived.

The Cantigas were written in the context of a popular mass movement venerating the Mother of God that spread across Christendom after the first millennium.1 Maternal figures had been venerated in many of the religions of antiquity—one example is the ancient Egyptian cult of Ast (Isis). The goddess was typically depicted breastfeeding her son Horus, an image analogous to those of the Virgin and Child (Fig. 1). The cult of Mary as goddess, which managed to divert attention even from the figure of Jesus, came late in the history of Christianity: Marian veneration began to take shape after the Council of Ephesus and became fervent during the 12th to 14th centuries. The Marian cult was especially popular in the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula and was spread by pilgrims along the Way of St James. King Alfonso, who described himself as the Virgin's troubadour in his prologue to the Cantigas, very probably wrote some of the poems himself.2

The songs are a rich source of information concerning medieval life. They contain rich descriptions of places, historical events, and more or less imagined scenarios. Along with the illustrations that accompany each poem, these songs help us grasp what court life was like. We learn of the musical instruments that were played, the dress and customs of courtiers, the food they ate, and of course the ailments they suffered. We must remember that many of the cantigas tell of people who ask Mary to intercede on their behalf because they seek a cure. Thus, we are given accounts of a large number of diseases of the time, although as we shall see, the stories are subject to multiple interpretations.

For this paper, we have selected some of the songs that describe dermatologic conditions and will attempt to analyze them from a medical and historical point of view. We have not transcribed each cantiga in full; rather, we present excerpts for commentary. Readers wishing to see the original texts are recommended to visit the website of Andrew Casson: Cantigas de Santa Maria for Singers (http://www.cantigasdesantamaria.com/). The information there is valuable for anyone who would like to delve more deeply into this monumental work.

Cantiga 54, “Toda saúde da santa Reinna” (All Health Comes From the Holy Queen): A Foul-Smelling Affliction of the Face Is Cured by the Virgin's MilkCantiga 54 tells the story of a monk with an ailment of the throat that spreads to his face, causing extensive tumors and pain (Fig. 2) and preventing him from swallowing. The odor that develops is described as “worse than that of a corpse,” Thinking him dead, his fellow monks administer the last rites. At this point the Virgin appears and washes his face “with a towel she carried.” Then, “taking out her breast, she sent milk into his mouth and onto his face, which became so clear that he seemed completely changed, as a swallow that renews its feathers.”

We cannot diagnose the disease based on this description, but it strongly suggests an infection of the craniofacial structures.

The 93rd cantiga, about a man with leprosy, offers another example of the medicinal use of milk. In fact, Alfonso's Marian repertory contains several songs praising the milk that fed the Savior, a concept that serves the purpose of illustrating that the nature of Jesus was human as well as divine. The curative power of the Virgin's milk was a familiar concept to the medieval mind. Even today, the cathedral in Murcia keeps a small vial with drops of milk for veneration as the Virgin's own, and a Bethlehem tradition designates a local site as the Milk Grotto, where Jesus was nursed by Mary. Many artists have depicted the Virgin sending a spray of her milk into the mouth of St. Bernard of Clairvaux. The event took place when as a young monk Bernard was told by his abbot to go and preach. Fearing he would disappoint, the saint prayed to the Virgin until he fell asleep. Mary appeared in a dream and bestowed the gift of eloquence by giving him milk from her breast.

The curative power of breast milk is a clear, consistent motif in Marian hagiography, one that has fascinated the faithful since the early days of the cult of the Virgin.

Cantiga 91, “A Virgin nos dá saúde e tólle mal” (The Virgin Gives Us Health and Takes Away Our Pain): On the Dreaded Ergotism, or St. Martial's FireThe story told in the 91st song takes place in France at the sanctuary of Soissons. The central event is mass poisoning by ergot, a fungus of the rye plant. The condition is called ergotism today but was then called St. Martial's fire. The cantiga says, “For the sins they had committed, God sent St. Martial's fire to punish and confound them…and as I have heard, it was the nature of that affliction to first make them cold and then burn them worse than fire…Because their parts fell away, nor could they eat or sleep, nor stand on their own feet, they preferred death to suffering such monstrous pain….” The Virgin appears, bathed in light, and miraculously cures them (Fig. 3).

This text gives an impeccable description of poisoning by ergot (Claviceps purpurea).3,4 Epidemics of ergotism, which have been well documented in many sources, devastated the medieval world for centuries, particularly in times of famine. Also known as St. Anthony's fire, the holy fire, or hell's fire, ergot poisoning was a common occurrence because rye was an important food staple at a time when white bread was only available to those in the upper strata of society. After the rye grain had been milled, its dark flour was easily masked the red powder of ergot mixed with it. Symptoms of ergotism included intense pain and cold in the extremities, due to vasoconstriction, followed by intense burning sensations, pain, distal necrosis, hallucinations, and convulsions. Occasional survivors were usually left severely deformed by loss of limb. Medicinal uses of ergot were known in the traditional Chinese pharmacopoeia, and in the 17th century ergot was employed to suppress puerperal hemorrhages.

St. Martial, who evangelized the Limousin region of France, has been revered in the area around Limoges since the early years of Christianity. His renown as a healer grew when the population of Aquitaine was decimated by ergotism in the 10th century. When the faithful turned to this saint to intercede on their behalf, the epidemic ended miraculously. In his life of St. Martial, Adémar of Chabannes (983–1043) went so far as to call him the 13th apostle who was present at the Last Supper and the crucifixion, claims that are reflected in the local iconography. Places associated with St. Martial even competed with Santiago de Compostela as pilgrimage destinations among the local population. In 1854, the bishop of Limoges petitioned Pope Pius IX to declare the saint a direct disciple of Christ, but the appeal was denied.

The cantigas were powerful promotional texts for Marian devotion, crediting Mary with miracles of such great impact that they exceeded those of St. Martial. The accounts sought to firmly establish that her ability to intercede in healing the sick outstripped that of any other in heaven, even the earlier healer of ergotism.

Several other cantigas provide descriptions of ergotism. The events in Cantiga 134 take place in Paris and include the miraculous regeneration of an extremity lost to the disease. Cantiga 19 tells of a condition referred to as “fire from heaven.” Cantiga 53 mentions a “wild fire” and also mentions leprosy, another scourge of the Middle Ages and one that could sometimes be confused with other diseases of the skin. Cantiga 105 clearly distinguishes between the two. In Cantiga 81, St. Martial's fire is said to “consume the flesh” of an afflicted woman, who hides her disfigured face behind a veil.

The treatment of ergotism was based on plants like mandrake or other analgesics, even though they could intensify the hallucinations caused by the disease. Treating physicians protected themselves with sponges soaked in vinegar and wore a mask like a bird's beak impregnated with aromatic substances to guard against contagion. Prayer and divine intercession remained the principal therapies, however, and it was considered important for a region to have relics of saints on hand or else nearby tombs where relics could be obtained. The Hospital Order of St. Anthony, which used the letter tau in blue as their symbol, were charged with caring for patients with ergot poisoning. Medieval spirituality embraced all these practices and beliefs, and it is likely that some patients improved with care, hygiene, and relief from the monotony of a diet based on rye bread made from the contaminated flour that was causing their misfortune.

Cantiga 93, “Nulla enfermidade non é de Saar” (No Disease Is Impossible to Cure): The Magical Healing of a Leper by Means of the Virgin's MilkFor the sin of lust, the protagonist of Cantiga 93 is punished with fulminant leprosy (gafeen) that covers his body with lesions, paradoxically causing ungovernable sexual desire. (In fact, lepers were widely believed at the time to be lustful.) Repentant, the patient withdraws to a hermit's hut—probably banished because of his condition—and prays a thousand Hail Marys to please the Mother of God. He is delivered from disease when Mary appears and decides to heal him with milk from her breast: “She took out her breast and anointed him with her holy milk.”

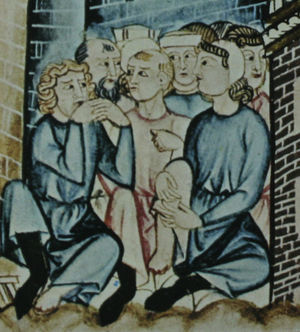

The illustration that accompanies the cantiga (Fig. 4) shows a man in bed prostrated by disease yet joyful in his expression. His skin shows signs of scaling or crusting, but his extremities have none of the ulcers or deformities typical of leprosy. We believe this case actually involves some other highly noticeable skin disease—perhaps scabies, psoriasis or eczema, but not the mere changes in pigmentation that come with such diseases as vitiligo or indeterminate leprosy.

Leprosy is one of the most often mentioned diseases in the Cantigas of Holy Mary. However, just as we exercise caution when interpreting other medieval texts, we should not rush to assume that the individuals described as lepers in these poems in fact had Hansen disease.4–6 Many conditions referred to as leprosy are in fact other diseases that manifest with a great variety of skin signs, such as psoriasis, scabies, or fungal infections, to mention only a few. The word gafo, however, is the medieval Galician-Portuguese term for a person with leprosy, and when it appears again and again in the Cantigas it does seem to refer to Hansen disease. The word also denotes a claw- or hook-shaped tool used to draw the string of a crossbow back to the nut, where it is fixed before the shot. This tool's shape resembles the clawlike deformities sometimes caused by peripheral neuropathy in tuberculoid leprosy. The conventional meaning of the Spanish word gafe to refer to a person who attracts bad luck may have been derived from gafo. Finally, the name of the river running through the Galician city of Pontevedra—Río dos Gafos—is a reference to an old lazaretto that housed lepers in the Campolongo neighborhood.

Leprosy is estimated to have afflicted 4% of the population in the Middle Ages, and there seems to have been a well-documented rapid spread of the disease in the 12th and 13th centuries. Lepers struck their fellow citizens with terror: the marks left by their disease, the deforming protuberances it left, the neurological impairment of arms and legs that obliged lepers to use crutches, and the numbness that developed did nothing to calm the widespread fears. The notion that lepers carried a moral burden came from the Book of Leviticus, where the afflicted are considered impure, sinners chastened by God. Paradoxically, however, the disease named in the Old Testament (tsará¿t) may not have been leprosy at all, but rather psoriasis, vitiligo or some other condition that causes the skin to scale.

The most common treatments for leprosy were bloodletting and the eating of snake meat—the latter grounded in the principle that one poison expels another.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Professor José Carro Otero, MD, of the Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, inspired in his students a fascination for anthropology, saints, bones and stones—invoking the phrase of José de Letamendi: “A physician who knows only medicine knows not even that.”

The images of Isis and Horus and the Virgen and Child (Figure 1) are in the public domain. They were obtained from http://www.es.mitologia.wikia.com/wiki/isis. The images in Figures 2 and 3 have been reproduced with the permission of the library of the Monastery of El Escorial. They come from the library's Códice Rico (Rich Codex) of the Cantigas of Holy Mary of Alfonso X the Learned. © Patrimonio Nacional.

Please cite this article as: Romaní J, Sierra X, Casson A. Análisis de la enfermedad dermatológica en 8 Cantigas de Santa María del Rey Alfonso X el Sabio. Parte I: introducción, el monje resucitado «lac virginis», el ergotismo y la lepra. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:572–576.