It is estimated that 10% to 15% of medicated patients develop adverse drug reactions (ADR). Despite the high prevalence of ADR, the identification of the trigger drugs remains a medical challenge, mainly in polymedicated patients. Our goal is to update the diagnostic tools to identify enhancer drugs of type B-ADR that compromise the skin and/or mucous membranes, in order to optimize patients’ follow-up and improve their quality of life. We develop the review in two stages: I- we review the pathophysiological mechanisms of the ADR; II- we developed the clinical approach for the identification of the triggering drug.

Entre el 10 al 15% de los pacientes medicados desarrollan reacciones adversas a medicamentos (RAM). A pesar de la alta prevalencia de RAM, la identificación del agente causal es un desafío diagnóstico y terapéutico, principalmente en pacientes que reciben múltiples medicamentos. Nuestro objetivo es actualizar los métodos de diagnóstico para identificar el fármaco desencadenante de RAM de tipo B que comprometa piel y/o mucosas, a fin de optimizar el seguimiento y la calidad de vida del paciente. Desarrollamos la revisión en dos etapas: I- repasamos los mecanismos fisiopatológicos de las RAM; II- desarrollamos el abordaje clínico para la identificación del desencadenante.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines an adverse drug reaction (ADR) as a response to a drug that is noxious and unintended and that occurs at doses normally used in man for the prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function.

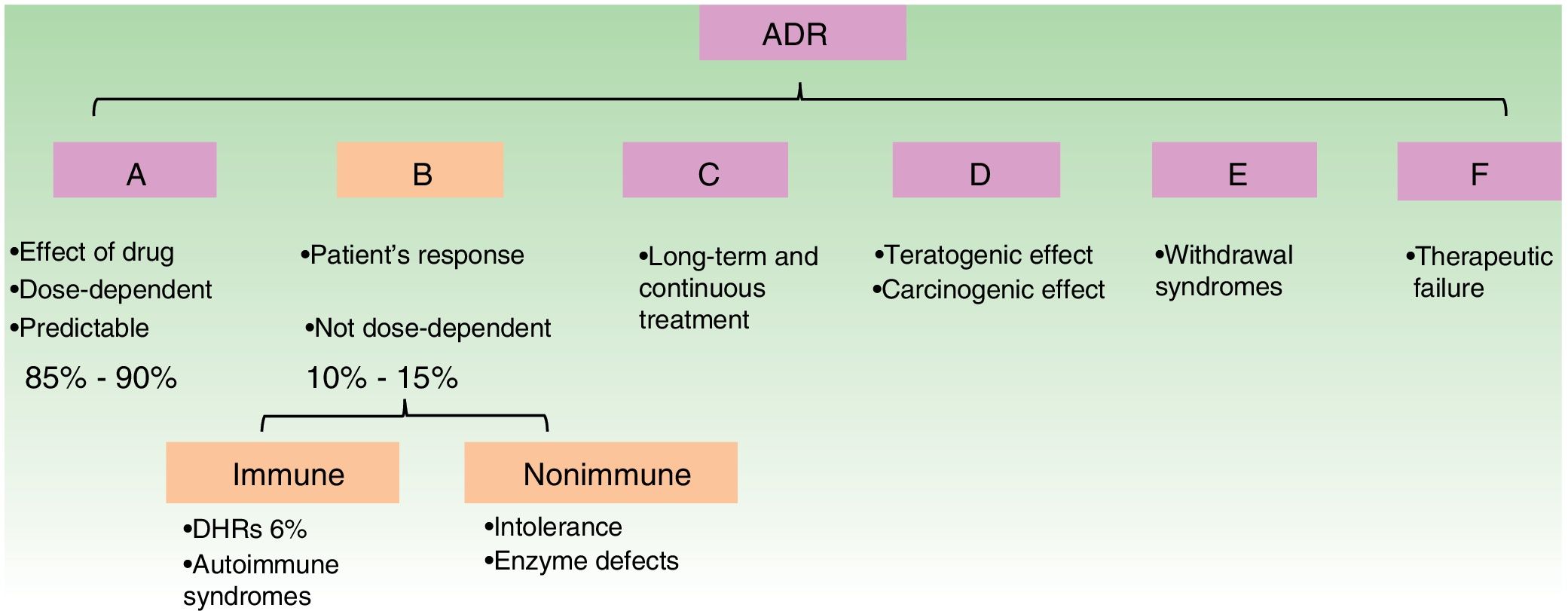

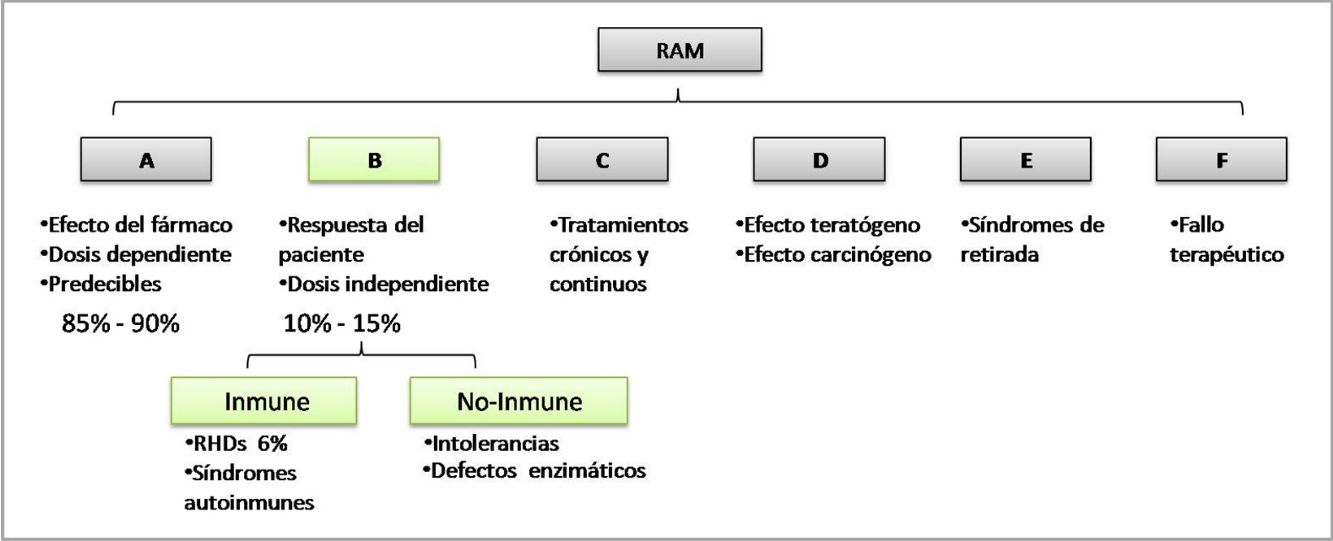

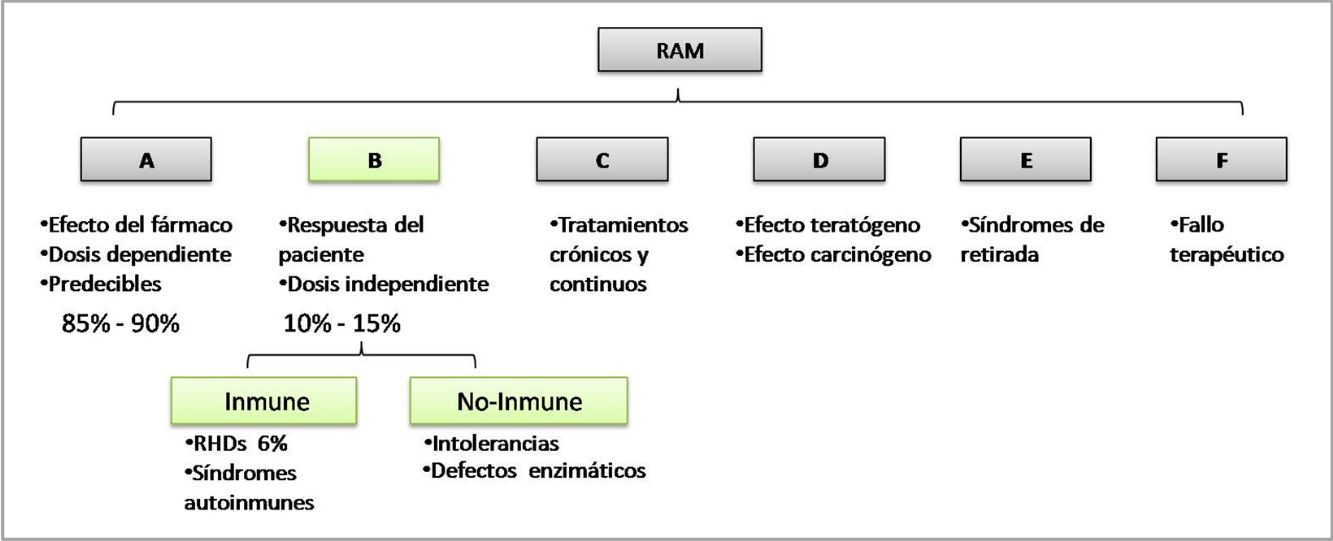

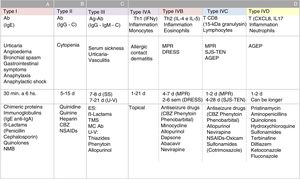

The WHO classifies ADRs according to their pathophysiological mechanism from A to F. Type B reactions cannot be predicted by the drug's mechanism of action and depend on patient susceptibility. They are known as idiosyncratic reactions and may be immune-mediated or non–immune-mediated (Fig. 1).1

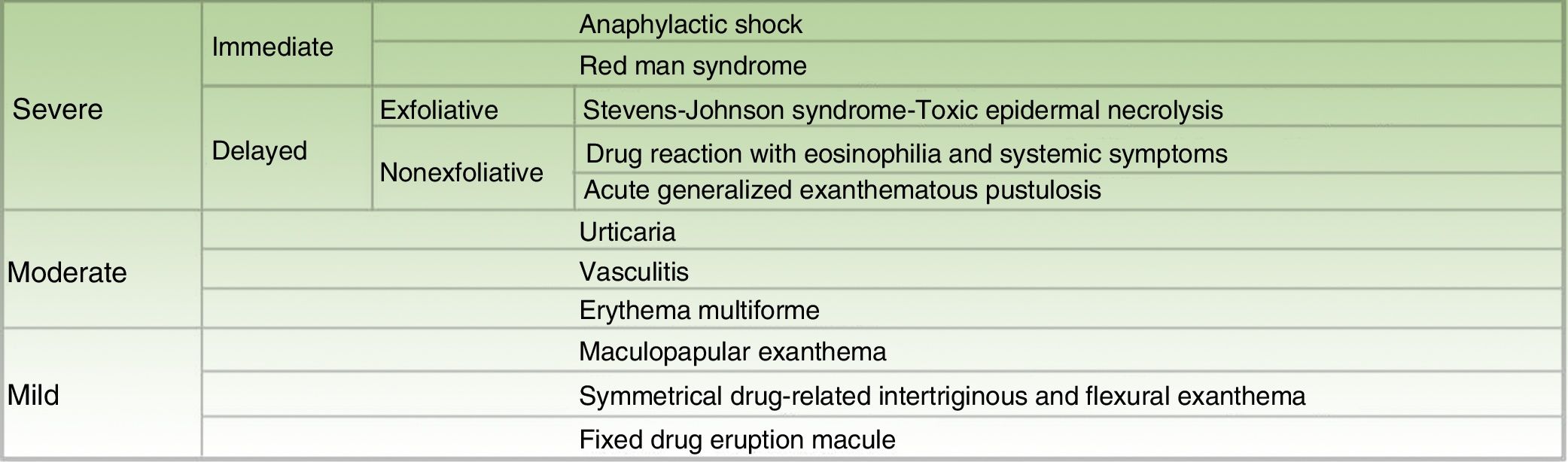

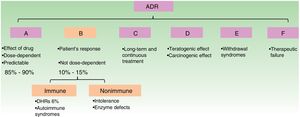

The manifestations of ADRs are very varied, and skin involvement is the most frequent. A cutaneous ADR (cADR) is defined as one that affects the skin and/or mucous membrane or adnexa.2 cADRs are classified in different ways. Figure 2 shows the various entities according to their clinical severity (Fig. 2).

It is estimated that 10% to 15% of medicated patients develop ADRs,3 which account for 3.5% of admissions in Europe.4 In the United States of America, it is calculated that 197 000 people die of ADRs every year. Despite the high prevalence of ADRs, identification of the causal agent continues to hamper diagnosis.5

Our objective was to update the tools used to identify the trigger of type B cADRs that compromise the skin and/or mucous membranes in order to optimize follow-up and patient quality of life (see additional material in Appendix 1).

Pathophysiology of adverse drug reactions: immunological aspectsSome pathophysiological mechanisms, such as drug hypersensitivity reactions (DHRs) are well described.6 Others, such as induction of drug-induced autoimmune syndromes (lupus erythematosus, bullous pemphigoid, and immunoglobulin [Ig] A bullous dermatosis), fixed pigmented eruption, and nonimmune anaphylaxis, are not known in detail.

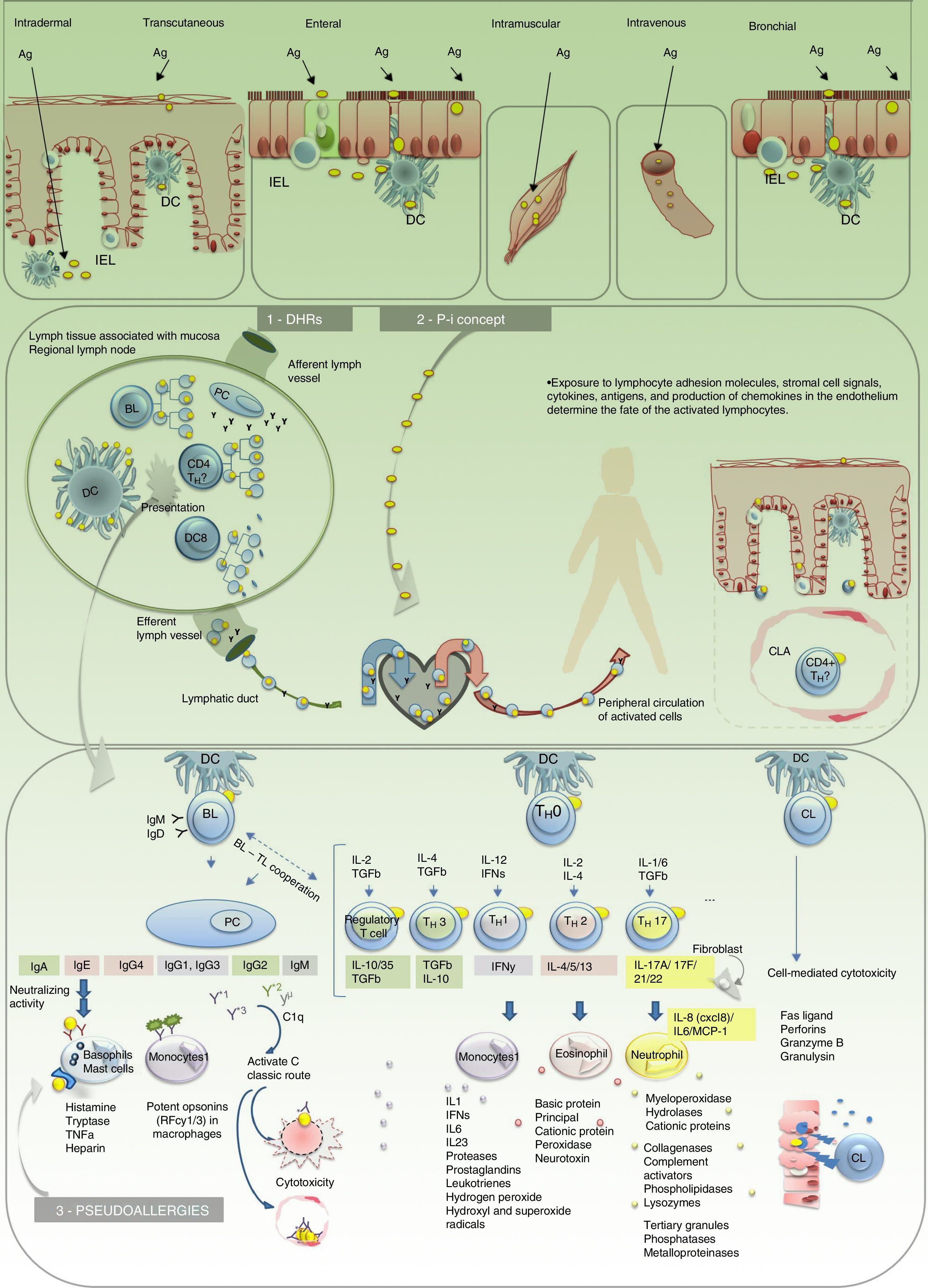

Immune-mediated type B ADRs are currently classified into 3 groups6: DHRs or allergies, pharmacological interaction of drugs with immune receptor (P-i) reactions (independent of antigen presentation), and pseudoallergies (non–IgE-mediated anaphylaxis-type reactions).

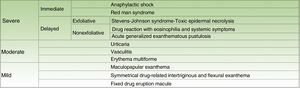

Drug hypersensitivity reactions (Fig. 3)DHRs affect more than 6% of the population.5Fig. 3

Pathophysiological model of adverse drug reactions. 1. Drug hypersensitivity reaction (DHR). 2. P-i concept. 3. Pseudoallergies. Ag indicates antigen; BL, B lymphocyte; CL, cytotoxic lymphocyte; CLA, cutaneous lymphocyte antigen; DC, dendritic cell; IEL, intraepithelial lymphocyte; IFN, interferon; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; PC, plasmocyte; TH, helper T cell; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

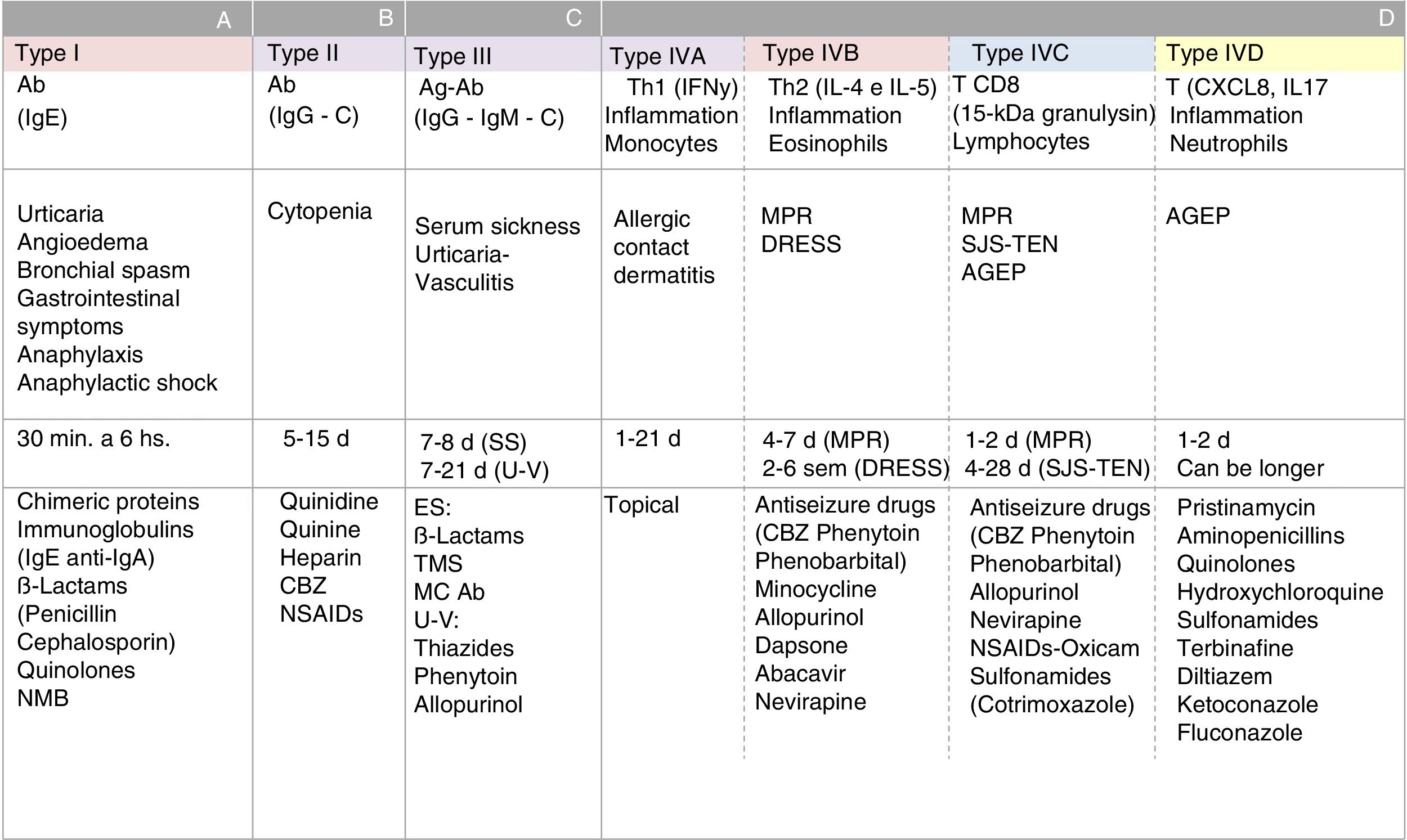

All hypersensitivity reactions commence with a sensitization stage involving the antigen, the cell that processes it and presents in its HLA (presenting cell), and the T lymphocyte that recognizes it via the T-cell receptor (TCR). The initial link between these 3 elements constitutes a trimolecular complex (HLA-antigen-TCR), which is known as the “first signal”. This interaction leads to a series of molecular changes known as the “second signal”. These changes determine a cellular or humoral effector response (mediated by T or B lymphocytes) and the generation of antigen-specific immunological memory. When drugs behave as antigens (or haptens), they can trigger ADRs. There are different types of hypersensitivity reactions. The Gell and Coombs classification, which was modified by Pichler,7 summarizes the pathophysiological mechanisms of DHRs (Fig. 4). The type of reaction triggered is determined mainly by the nature of the antigen and the cytokine environment. The latter varies depending on the functional profile of the organ involved in the reaction, the route of administration of the drug, and the immunological activation status of the individual. For example, drugs with antigenic properties that are administered via the skin or mucous membrane come into contact—in both cases—with interface or border tissues that are very rich in immune cells but physiologically adapted to fulfill various functions (different functional profile). Activation of intraepithelial lymphocytes in the skin is associated with opsonization and inflammatory defense profiles, whereas the mucous membrane of the digestive tract is associated with the development of neutralization and tolerance responses via activation of type 3 helper T cells, regulatory T cells, and abundant IgA (neutralizing globulin). However, when the mucous barrier is altered and becomes inflammatory (individual immune activation status) or the patient's modulatory mechanisms fail, the patient is prone to lose peripheral tolerance and develop hypersensitivity responses. This is how an antigen that has entered the body via the digestive tract can become an allergen and induce symptoms locally or at a distance. The same occurs with the skin, for example, when the skin barrier is altered, as is the case in atopic dermatitis, and becomes more susceptible to allergic contact dermatitis (type IV-A hypersensitivity reaction).8

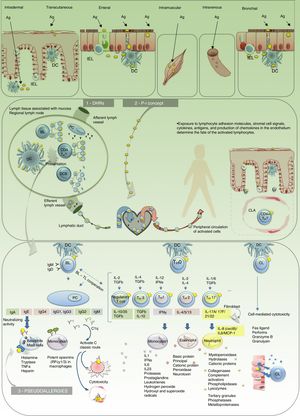

Classification of hypersensitivity reactions according to the pathophysiology of adverse drug reactions. A, type I hypersensitivity reactions; B, type II hypersensitivity reactions; C, type III hypersensitivity reactions; D, type IVA, IVB, IVC, and IVD hypersensitivity reactions; Ab indicates antibody; Ag, antigen; AGEP=acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; CBZ, carbamazepine; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic reactions; Ig, immunoglobulin; MC, monoclonal; MPR, maculopapular rash; NMB, neuromuscular blockers; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; SJS-TEN, Stevens Johnson syndrome-toxic epidermal necrolysis; SS, serum sickness; U-V, urticaria-vasculitis.

This concept can be used to explain type B ADRs that lack a sensitization stage. In these cases, it is postulated that the first signal is given by the direct interaction between HLA and the drug or between the TCR and the drug, regardless of processing and presentation by a presenting cell, thus constituting a reversible biomolecular complex, in contrast with the classic trimolecular presentation of ADRs. In P-i reactions, several theories have been put forward in the absence of an effect of the presenting cell for development of the second signal, as follows: (1) P-i reactions only occur in T cells stimulated by another antigen (chronic infections, autoimmune diseases); (2) the drug binds to HLA and leads to a change in the conformation, thus generating new HLA for which the individual does not present tolerance (e.g., in the response to alloantigens in organ transplantation)9; and (3) the second signal is given by the interaction between the drug itself and the target receptor, when this acts on presenting cells.10 The effector cell can be activated by any of these 3 mechanisms. Unlike hypersensitivity reactions, P-i reactions only activate cellular T lymphocyte–mediated but not humoral responses. Clinically, these can present as any cellular immunity–mediated ADRs such as maculopapular rash, Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.6

Pseudoallergies (Fig. 3)Pseudoallergies are similar to type 1 ADRs and are caused by degranulation of mast cells and basophils, although via IgE-independent mechanisms. These reactions include red man syndrome caused by rapid infusion of vancomycin and are associated with drugs classed as histamine releasers, such as plasma expanders, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and pyrazolones. Little is known about the pathophysiology of these reactions, and there are no specific tests for studying them.

Clinical approach to adverse drug reactionsWhile this article is not aimed at addressing treatment of cADRs, it is important to remember that severe cADRs make it necessary to act based on clinical suspicion. Administration of the suspect agent should be stopped immediately, without waiting for confirmation.

Appropriate clinical historyThe clinical history should be aimed at identifying the drug.5 The main information to be included is as follows:

- •

Exhaustive information on the event.

- •

Possible trigger(s). Drug, herb, or homeopathic formulation, exposure to chemicals at work or with hobbies.

- •

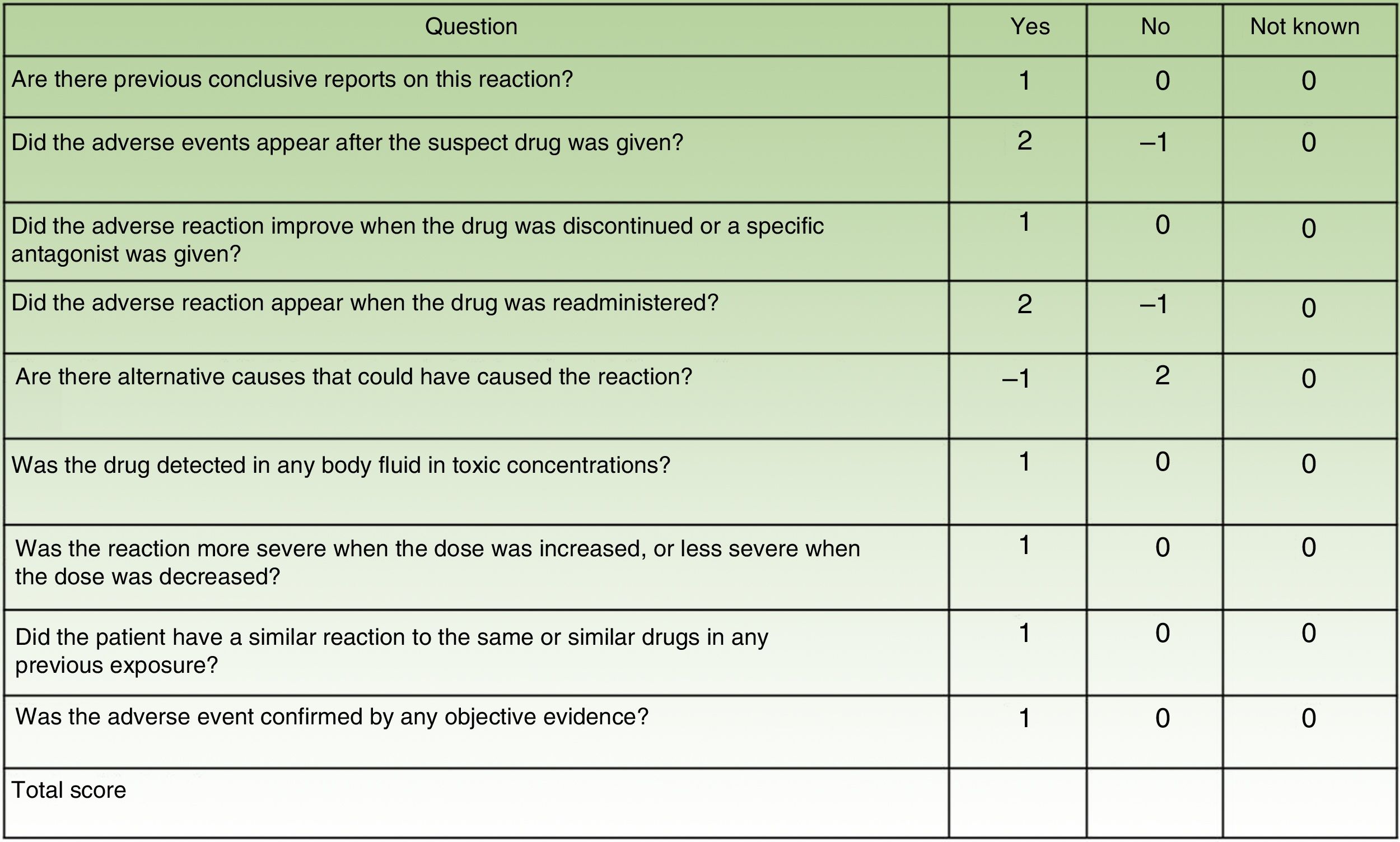

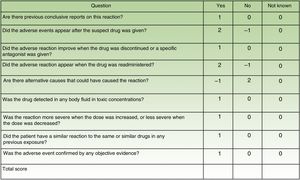

For each suspect drug, it is essential to determine the causal relationship with the reaction (Naranjo scale [Fig. 5]).11

- •

The clinical presentation of the episode and the temporal link with the suspect drug make it possible to assume the pathogenic mechanism involved.

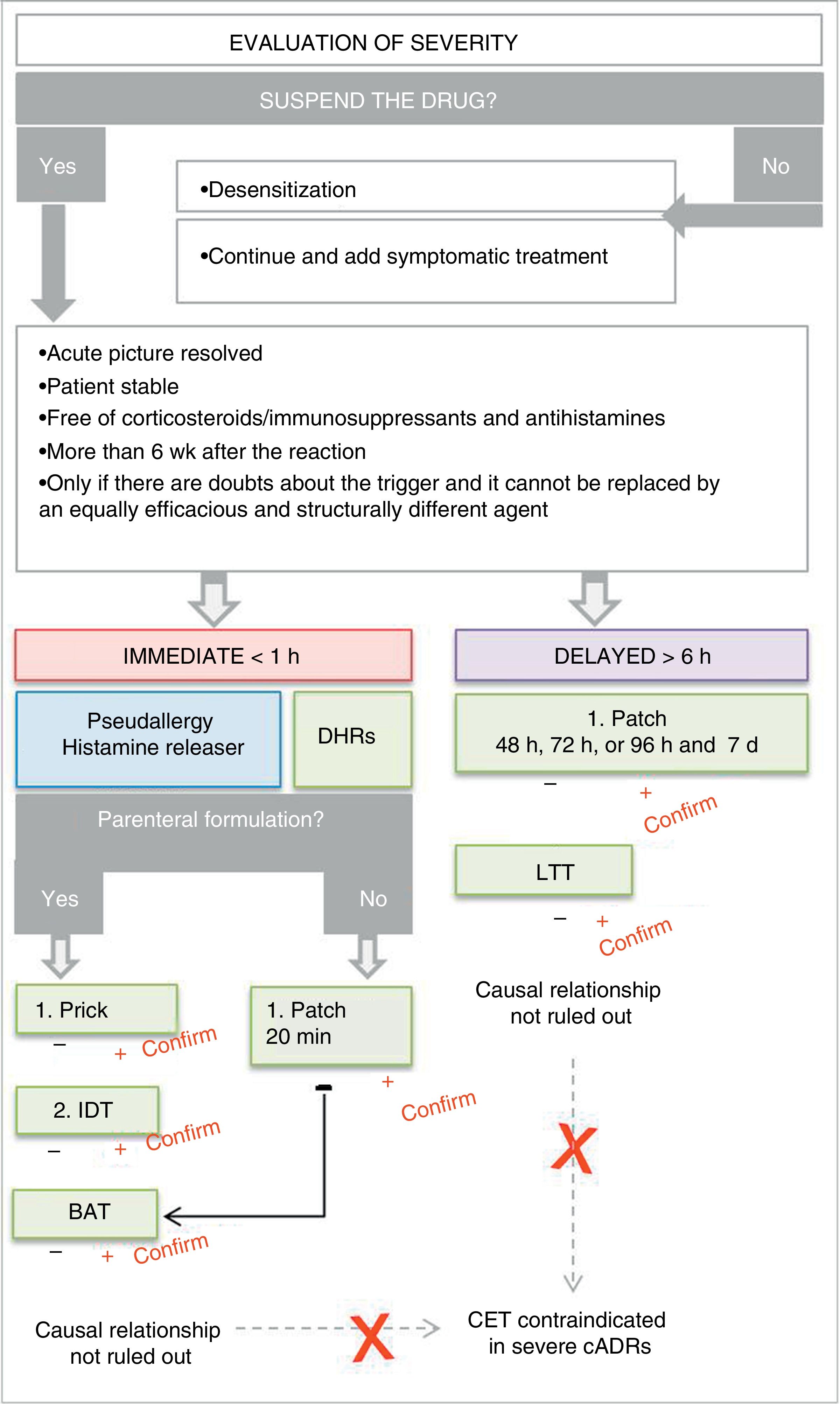

If the analysis of causality remains unclear with respect to identification of the trigger agent, we can turn to diagnostic tests. These are used only when there is no equally effective pharmacological alternative to the drug and the risk-benefit ratio is favorable. We should wait 4 to 6 weeks to ensure complete resolution, and the patient should be totally stable and free from immunosuppressive medication or cardiovascular modulators (ß-blockers) for immediate reactions. No study will be carried out in the following cases: (a) error in determining a causal or etiological relationship (in time, with postreaction tolerance, reaction without exposure); (b) when an alternative diagnosis can explain the reaction (viral eruption); and (c) in the case of a possible uncontrollable and potentially life-threatening severe reaction; (d) DHR testing is never carried out before exposure.

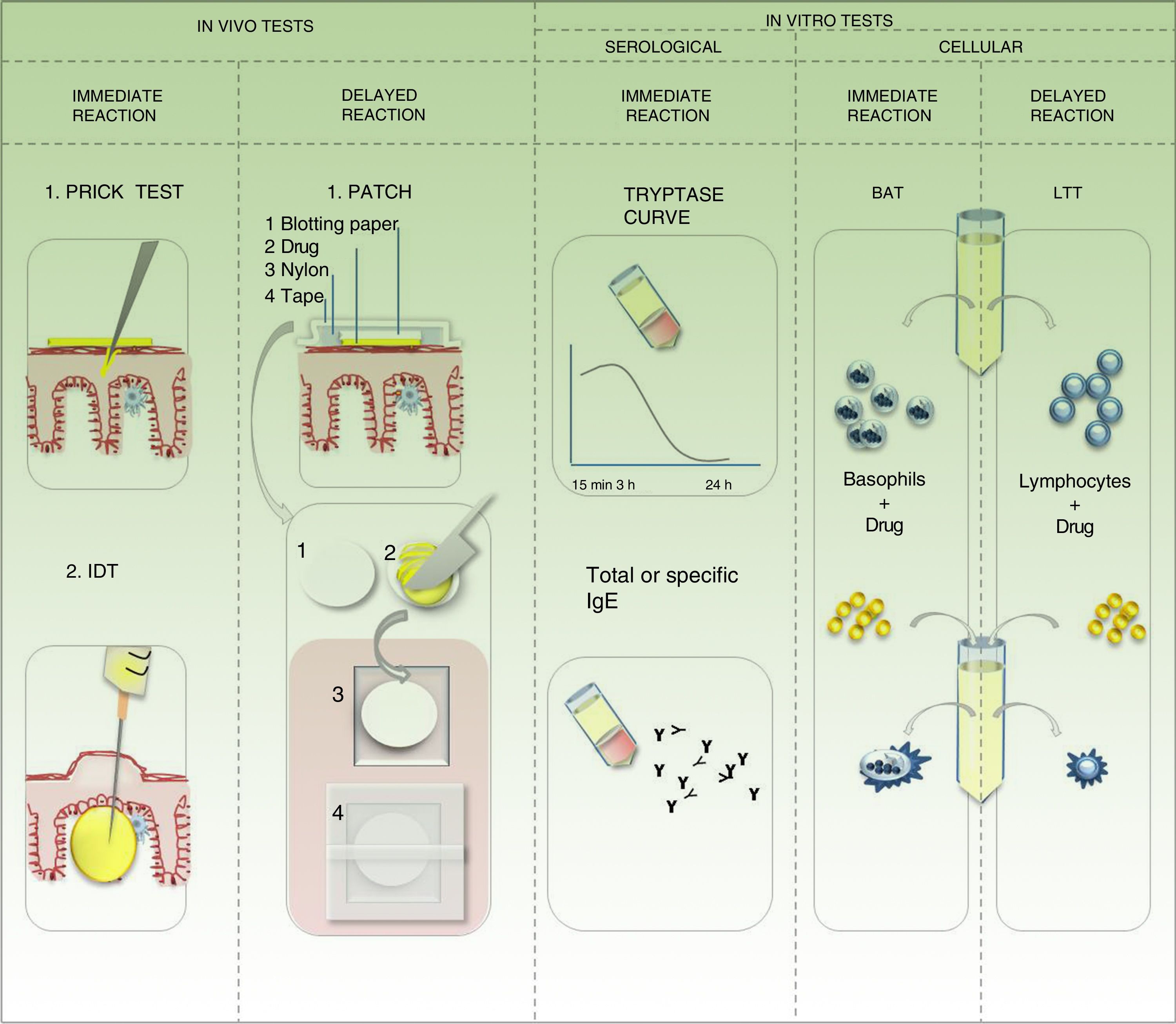

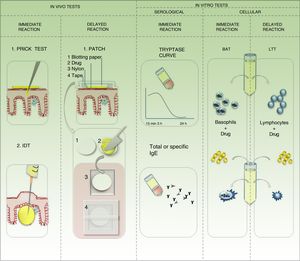

In vivo studies for identification of the drug triggering a hypersensitivity reaction5,12,13Prick testPrick test is the approach of choice for type 1 DHRs. The injectable drug is applied on the volar aspect of the forearm by means of a superficial puncture. The test can be performed with the suspect agent, although the most suitable approach is to use the active ingredient and the excipients separately. In the case of urticarial reactions, the test should start with serial dilutions (10-3, 10-2, 10-1). Controls should be applied, as follows: negative (with physiological saline 0.9%) and positive (with histamine at 10mg/mL). A positive response is defined as a wheal at the puncture site that is 3mm in diameter after 20minutes and no reaction with the negative control. This result confirms a type 1 DHR; the presence of specific IgE is shown in vivo. If the drug is a histamine releaser, then the result could be a false positive caused by pseudoallergy. A negative result in the prick test never rules out a causal relationship (Fig. 6).

Intradermal testIntradermal testing is performed if the result of the prick test is negative and there is strong clinical suspicion of a type 1 DHR. The drug should be applied at the concentrations stipulated in international guidelines. Dilutions should be prepared with physiological saline 0.9% within 2hours before application and under aseptic conditions with a laminar flow hood. If the test dilution is not described, then the test should start with a concentration of 10-4, which should gradually be decreased by 1 decimal place to no more than 0.04mL of solution injected by puncture. This generates an intradermal wheal measuring 4 to 6mm in diameter. The reading is at 30minutes, 6hours, and 24hours. The patient remains under observation during the first 6hours, with specific monitoring of heart rate and blood pressure. The test should be performed using a peripheral venous access and infusion of glucose solution. If a 10-mm wheal is generated at 30minutes, the result is considered positive. If there is no reaction after 30minutes, the concentration can be increased until the pure concentration is reached. A reaction during the first 6hours confirms a type 1 DHR. It is also important to take into account the possibility of false positives caused by pseudoallergy. When the reaction is late, then the DHR is delayed, the size of the wheal should be recorded in the clinical history, and the patient should be followed up at 1 week. If an early reaction is negative, then the patient should be contacted at 1 week to confirm the negative result. A negative result does not rule out a causal relationship (Fig. 6).

Patch testThe patch test is the approach of choice when a delayed reaction is suspected. Although less sensitive than the previous 2 options, it can be an alternative if no injectable formulation is available. Ideally, the active ingredient should be tested separately from the excipients. The concentration to be tested is standardized. If this is not known, the pure drug is formulated at 5% or 10%. If the pure drug is not available (active ingredient), the suspect pharmaceutical formulation can be tested at a maximum of 30%, and the formulation cannot be stored for more than 24hours. If the capsule is available, it should be hydrated and dissolved so that it can be tested separately from its content. In this case, if the suspect pharmaceutical formulation is used in the case of a positive result, we cannot determine whether the allergen is an excipient or the active ingredient. In order to reduce the risk of false positives caused by irritation, the drugs should be formulated in petrolatum and/or distilled water. If a commercial system is not used, then the in-house product should be prepared with care (Fig. 6). The formulation should be applied on healthy skin of the forearm or back, and the first reading should be taken after 20minutes. This rules out the possibility of immediate allergy or irritant reaction. The patch is occluded for 48hours, after which time it is uncovered, the residue is removed without rubbing, the skin is left open to the air for 20minutes, and the first late reading is made. Readings are then taken at 72 or 96hours and at 1 week. If drug-induced photoallergy is suspected, the drug should be tested in a patch and with photostimulation at 48hours (UV-A 5J/cm2) in a separate patch. In the case of fixed pigmented erythema, one patch should be placed over healthy skin and another in the area of the fixed eruption. A positive response indicates a reaction ranging from a mild reaction with erythema and edema to an intense reaction with vesicles-blisters or erosions. Irrespective of the grade of the reaction, a positive patch test result confirms DHR. However, a negative result does not rule out a causal relationship. The patch test is useful for proving reactions such as maculopapular rash, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms, and symmetrical drug-related intertriginous and flexural exanthema. Sensitivity varies with the drug and the clinical presentation of the reaction. In a series of 134 patients, Barbaud et al.14 demonstrated that the overall sensitivity of the test was close to 60%. Sensitivity decreases in the case of macular exanthema (fixed pigmented erythema), urticarial reactions, and exfoliative forms (SSJ-TEN). Patch testing is not useful in organ-specific reactions.14

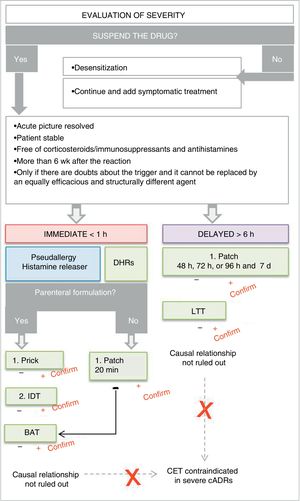

Controlled exposure testingControlled exposure testing is contraindicated in cases of severe cADR and should only be applied when it seems clinically improbable that the suspect drug is the trigger. In most cases, this exposure test occurs accidentally (ie, not under controlled conditions), when the patient is re-exposed to the drug inadvertently and reports recurrence of the symptoms. Controlled exposure is the only test in which a negative result rules out a causal relationship with the suspect drug. The drug is administered at increasing doses under the supervision of an allergologist or trained physician. Controlled exposure testing is the gold standard for establishing a causal relationship, despite the difficulties involved in performing it.

In vitro studies for identification of the triggering drug in drug hypersensitivity reactions13Basophil activation testThe basophil activation test is useful when the pharmaceutical formulation is not available in injectable solution and we need to test for a type 1 DHR. This test involves placing the patient's basophils in culture against the drug and measuring the expression of activation receptors (CD63, CD203) using flow cytometry. The probability of a causal relationship is expressed as positive or negative according to the percentage of cells that are activated.

Measurement of serum tryptase in peripheral bloodMeasurement of serum tryptase is useful for type 1 DHRs. Tryptase is found in mast cell granules and is released after activation. The curve of the measurements is plotted at 15minutes, 3hours, and late at 24hours after initiation of symptoms.

Measurement of specific immunoglobulin ESpecific IgE panels are more frequently used for foods or environmental allergens based on techniques such as radioimmunoassay or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The panel for diagnosing drug allergy is fairly limited. In fact, a type 1 DHR does not always progress with increased IgE; therefore, a negative result does not always rule out a causal relationship.

Lymphocyte transformation testThe lymphocyte transformation test is useful in the case of suspected delayed reaction. It consists of the incubation of lymphocytes extracted from peripheral blood and the suspect drug after 48hours to 7 days. The result is positive if there is proliferation of lymphoblasts. This is the test of choice for severe exfoliative delayed DHRs (SSJ/TEN) or specific organ reactions, since controlled exposure testing is contraindicated.

Genetic susceptibility studiesThe association between specific HLAs and the risk of severe cADRs was demonstrated for some drugs in Asians. The presence of allele HLAB*5701 confirmed a positive predictive value of 100% and a negative predictive value of 97% for hypersensitivity reaction to abacavir, even in different ethnic groups, similar to the case of allopurinol and HLAB*5801. However, other associations are weaker when populations with different ancestries are compared.9

In the first place, we should identify the real need to use a laboratory test to confirm the causal relationship after having applied the imputability analysis. Given this situation, and in accordance with the pathophysiological mechanism and the pharmaceutical formulation, the most appropriate test should be selected. It is important to take the patient's underlying conditions into account in order to avoid false negatives. It is worth noting that any positive test result is confirmatory, although negative results do not rule out a causal relationship, with the exception of controlled exposure tests15-17 (Fig. 7).

Algorithm for hypersensitivity testing for adverse drug reactions. Abbreviations: BAT indicates basophil activation test; IDR, intradermal reaction; CET, controlled exposure test; cADR, cutaneous adverse drug reaction; DHR, drug hypersensitivity reaction; IDT, intradermal test; LTT, lymphocyte transformation test.

Despite the high prevalence of cADRs and the importance of identifying the causal agent, reactions continue to be a challenge, especially in polymedicated patients. Unfortunately, no test is 100% sensitive and safe for the detection of the triggering drug. Therefore, all of the results recorded, ranging from the analysis of imputability to additional testing, are useful tools that enable us to verify a causal relationship with the suspect drug.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Zambernardi A, Label M. Reacciones cutáneas adversas a medicamentos: cómo identificar el desencadenante. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:699–707.