Congenital fascial dystrophy (CFD) or stiff skin syndrome is a rare skin disease that was described in 1971 by Esterly and McKusick.1 The condition is characterized by noninflammatory fibrosis of the subcutaneous cellular tissue and of the muscle fascia, leading to hardening of the skin and interference with movement of the underlying joints. It can be hereditary and show a very variable degree of severity, sometimes causing minimal symptoms, as in the case we describe below, in which the diagnosis was made in adulthood.

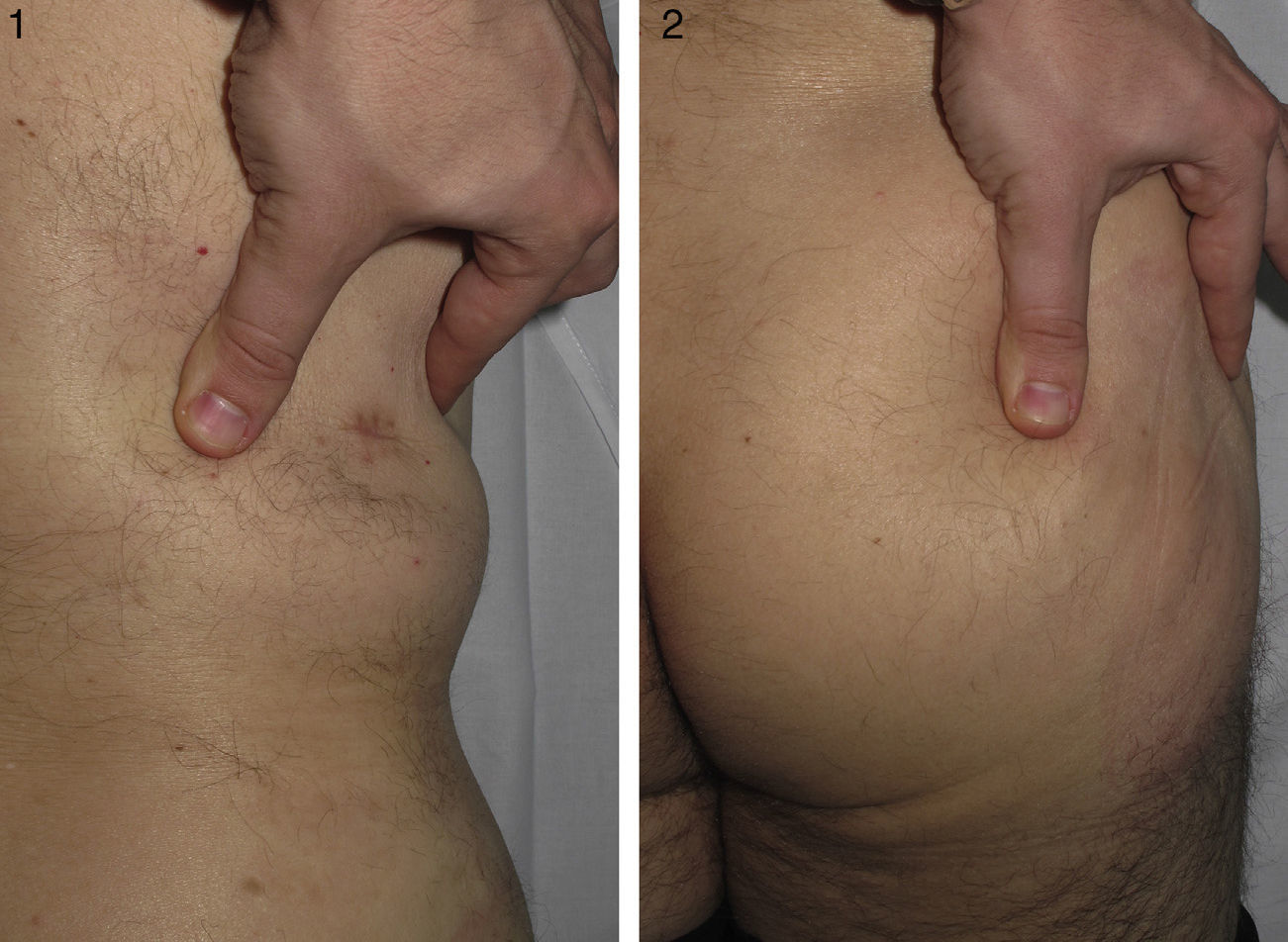

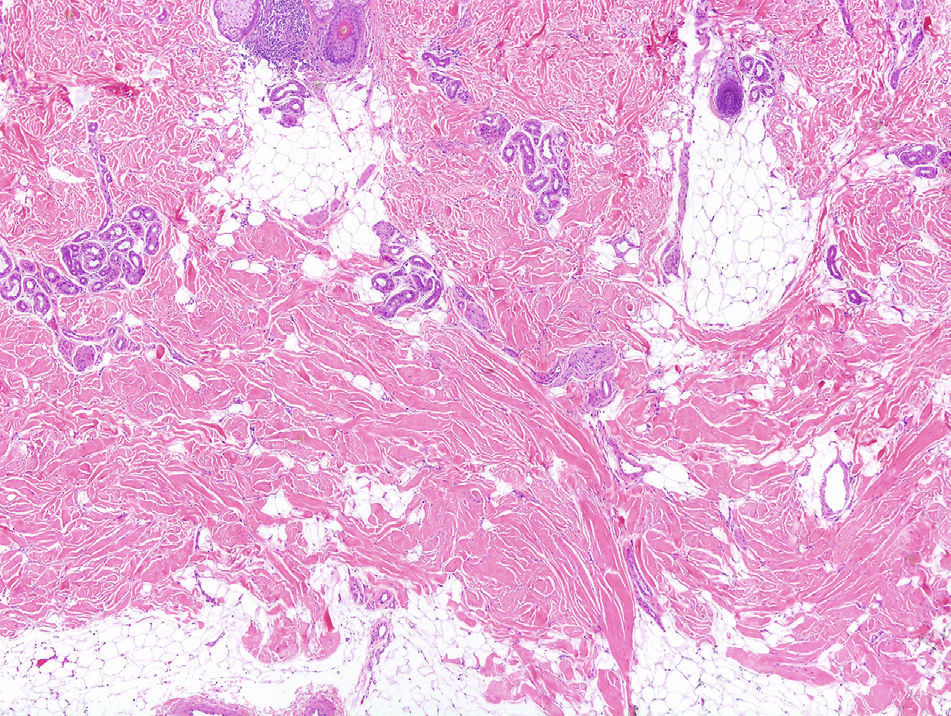

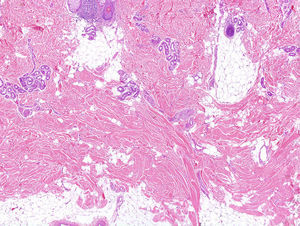

The patient was a 46-year-old man with no past medical history of interest. He had been referred from another hospital with a clinical suspicion of morphea profunda that had not responded to treatment with oral corticosteroids. The patient stated that since childhood he had had difficulty performing certain movements, such as flexing the trunk, and that it had been impossible to administer intramuscular injections into the right buttock. He also said that his daughter had similar symptoms. Examination revealed difficulty raising a skin fold in the lumbar and right gluteal regions (Figs. 1 and 2), where the skin was hard to the touch, and a limitation of movement of the right hip, particularly flexion. Investigations performed at the previous hospital included an autoimmunity study that was normal, magnetic resonance imaging, which excluded bone or muscle involvement, and skin biopsy, which was reported to be consistent with morphea profunda. The biopsy was reviewed: thickened collagen was observed in a horizontally oriented lattice pattern in the deepest layers of the dermis, and there was no inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 3). We made a diagnosis of CFD based on the clinical and pathological findings, and physiotherapy was recommended.

CFD is a very rare disorder and descriptions are scarce in the literature.2 It affects men and women equally, and a family history is found in 30% of patients. In the case described, the targeted history enabled us to identify a daughter with similar symptoms, though, at the time of writing, no additional tests had been performed to confirm the diagnosis.

The pathogenesis of this disease was unknown until recently.3 However, Loeys et al.4 discovered that all affected individuals had a mutation in the fibrillin-1 gene. This protein, which is also mutated in patients with Marfan syndrome, is mainly involved in the formation of microfibrils (formed of fibrillin polymers), which, together with elastin, form the elastic fibers. This mutation leads to a disorganized accumulation of microfibrils in the dermis; this can be observed on confocal or electron microscopy. These accumulations produce abnormal activation of another molecule, transforming growth factor (TGF-β), which has the ability to promote collagen deposition in the dermis. The increased TGF-β levels in patients with CFD leads to greater collagen deposition in the deeper regions of the dermis, the subcutaneous cellular tissue, and the muscle fascia.

Clinical manifestations are usually present at birth, but they can also appear during the first 6 years of life.2 Patients with CFD have clearly circumscribed areas of hardened skin with no visible changes to the skin surface; these areas arise particularly around the pelvic or shoulder girdles and on the proximal areas of the thighs.5 Less common findings include hypertrichosis, hyperpigmentation in the affected areas,6 and the presence of subcutaneous nodules on the distal phalanges of the fingers.4

The main problem caused by this condition is limitation of joint movement. In the majority of patients this limitation is mild and does not interfere excessively with daily life; however, changes can sometimes be very widespread and can even limit lung capacity.2 If the symptoms are mild, the diagnosis may not be made until adult life.

Not only the clinical manifestations but also the microscopic findings are very important. Microscopy reveals a proliferation of collagen tissue, particularly in the muscle fascia and in the subcutaneous cellular tissue, although there are reports of cases in which only the reticular dermis is affected.7 It is important to note that involvement of the muscle fascia is not a prerequisite for making the diagnosis. The term congenital fascial dystrophy was proposed in the original description of the disorder because the fascia was found to be affected in all the patients with this diagnosis. However, not all cases diagnosed since that time have had fascial involvement. The most characteristic microscopy finding suggestive of CFD is not so much the site of the excess collagen, but its arrangement in a lattice-like array.7 Other typical features are the absence of an inflammatory infiltrate and the presence of mucin.

Finally, to confirm the diagnosis it is important to exclude the presence of specific autoantibodies and of structural bone or muscle lesions.2

The main condition to be taken into account in the differential diagnosis is morphea profunda.2 In contrast to CFD, morphea profunda usually has an asymmetric distribution, it does not present at an early age, visible skin changes are usually present, and, microscopically, the collagen is compact. In addition, in the initial phases there is usually a lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory infiltrate. In pansclerotic morphea of childhood, although the sclerotic process is also deep, as in CFD, the presence of very evident skin changes, including ulcers and pigment disorders, makes differentiation easy.8

No effective treatment for CFD exists. Numerous drugs, including topical and oral corticosteroids, methotrexate, and psoralen–UV-A, have been tried and the results have been very poor with all of them.2 Only physiotherapy appears to be able to improve joint comfort and movement.

The interest in knowing CFD and being able to make a correct diagnosis derives mainly from the need to differentiate it from morphea profunda, a condition with similar clinical and microscopic characteristics. Only in this way is it possible to avoid the administration of potentially harmful drugs that, in the case of CFD, would be totally ineffective.

Please cite this article as: Plana Pla A, Bielsa Marsol I, Fernández-Figueras M, Ferrándiz Foraster C. Distrofia fascial congénita o síndrome de la piel rígida: presentación de un caso. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:805–807.