A 55-year-old man visited the emergency department with clinical signs and symptoms that had appeared some days earlier, consisting of progressive dyspnea accompanied by fever of up to 39 °C, productive cough, and flat, red-violaceous reticulated lesions with a purplish appearance on the left outer ear (Fig. 1), left malar region, right nostril, and both arms. The patient was an ex-intravenous drug abuser and had a history of stage-2 infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus, hepatitis C virus, which was cured spontaneously, and presented chronic neutropenia. Laboratory tests showed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia, creatinine levels of 6 mg/dL, procalcitonin of 3.74, C-reactive protein (CRP) of 313, and a glomerular filtration rate of 9 mL/min. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCAs) and lupus anticoagulant were positive, whereas cryoglobulins were negative. A chest x-ray showed bilateral disperse alveolar-interstitial infiltrates and the patient was therefore diagnosed with lobar pneumonia and acute kidney failure.

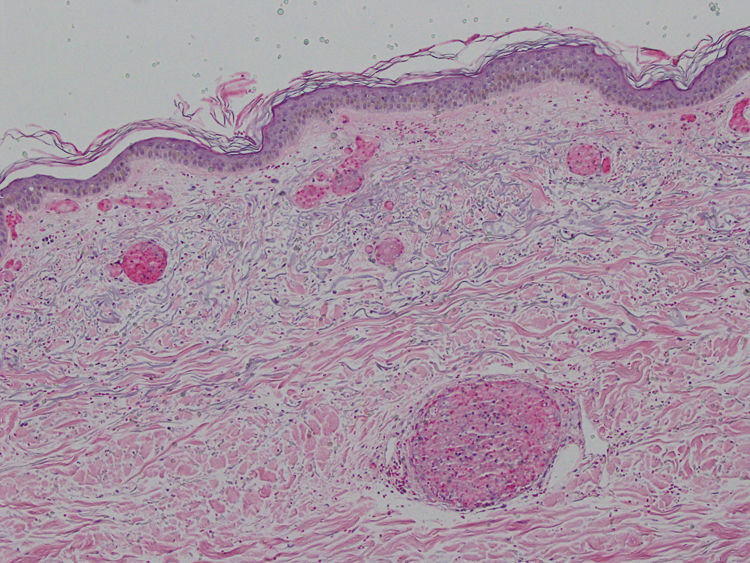

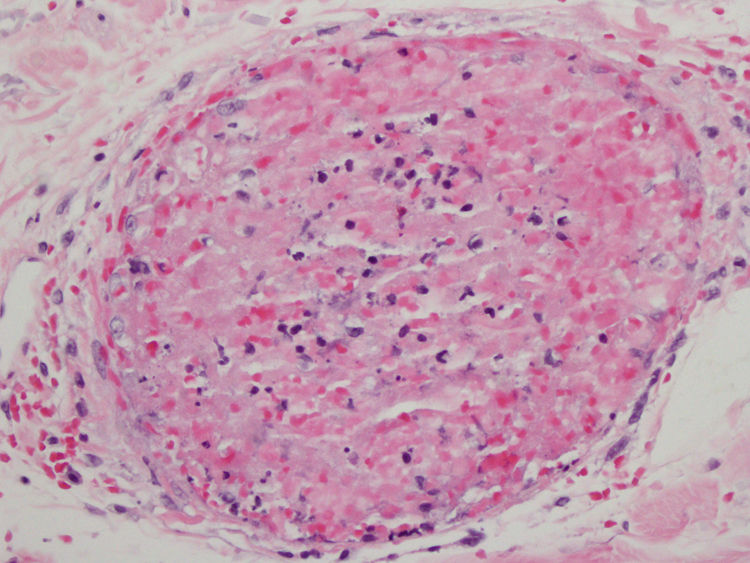

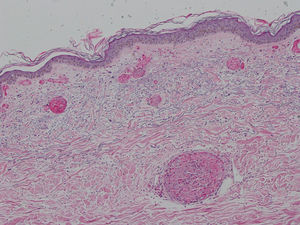

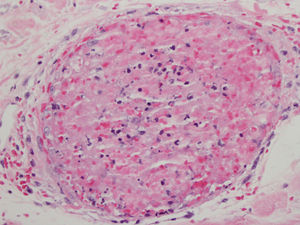

A punch biopsy of one of the skin lesions was performed and revealed massive occupation of the capillaries by mixed thrombi, with some trapped polymorphonuclear cells, without the characteristic abnormalities of leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Figs. 2 and 3). The differential diagnosis included thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, disseminated intravascular coagulation, cryoglobulinemia, and retiform purpura associated with cocaine use. The first 2 entities were ruled out clinically and the third was ruled out due to the absence of cryoglobulins. The patient subsequently admitted to using cocaine. The skin lesions remitted after administering treatment with methylprednisolone and the patient was referred to a mental-health center for cessation of cocaine use.

Levamisole is an anthelminthic drug that, due to its immunomodulatory effect, was used in the past to treat rheumatoid arthritis, collagenopathies, inflammatory bowel disease, pediatric nephrotic syndrome, and cancer. In 2000, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) withdrew the drug from the market due to its severe adverse effects, such as vasculitis and blood disorders (especially agranulocytosis)1–3; the drug was, however, maintained for veterinary use.4,5

It has gained notoriety since 2008 through its use as an adulterant for cocaine due to its similar consistency, its availability, and its synergic activity.2 A syndrome has therefore been described in users of this drug that is characterized by retiform purpura,1–3 pauci-immune crescentic glomerulonephritis, pulmonary hemorrhage with vasculitis, pulmonary hypertension,2,5 and arthritis deformans, with variable frequency.6 Serology reveals higher titers of perinuclear antineutrophilic antibodies than in idiopathic vasculitis. Its association with antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), and antiphospholipids such as lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin has also been reported.2,3 A study carried out in Spain in 2009 determined that 48% of cocaine samples studied contained levamisole.7

The most notable symptom, and the one that causes patients to seek consultation, is the cutaneous symptom.2 It has also been found that 60% of these patients have blood disorders and between 95% and 100% have high ANCA titers.3 It usually manifests as retiform purpura involving the outer ear, zygomatic arches, and extremities, while sparing the torso. Typical histopathology findings include small-vessel leukocytoclastic vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis of the vascular wall, extravasation of erythrocytes, karyorrhexis and angiocentric inflammation, and multiple fibrin thrombi in the vessels of the superficial and deep dermis.1–3,5 These findings may present together or separately; microvascular thrombosis is the most consistent of these findings1 and was the only one found in our case.

Cascio and Jen2 have suggested naming this constellation of abnormalities cocaine/levamisole-associated autoimmune syndrome (CLAAS). As well as the retiform purpura with the characteristic pattern, our patient presented a thrombotic vasculopathy, thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, lupus anticoagulant, and ANAs. Although the patient presented acute kidney failure, there is no clinical confirmation that this was due to the use of cocaine and levamisole.

The diagnosis of CLAAS is by exclusion. It should be considered in all patients with a history of cocaine use who present with purpura of the characteristics described above, joint pain, neutropenia, and high ANCA titers5 in the absence of other apparent etiologies.8 The basis of treatment is ceasing cocaine, and thus levamisole, use.1,2,5 The literature shows treatment data similar to those for primary vasculitis: immunosuppression, anticoagulation, and antiaggregation.6 In our patient, the dermal lesions remitted after treatment with methylprednisolone.

FundingThis study has not received funding of any kind.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank the personnel of the anatomic pathology and dermatology departments of the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, without whose support, this study would not have been possible.

Please cite this article as: Cevallos-Abad MI, Córdoba-Iturriagagoitia A, Larrea-García M. Síndrome autoinmune cocaína-levamisol. Presentación de un caso. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2020.02.010