The discovery of new autoinflammatory syndromes and novel mutations has advanced at breakneck speed in recent years. Part 2 of this review focuses on vasculitis syndromes and the group of histiocytic and macrophage activation syndromes. We also include a table showing the mutations associated with these autoinflammatory syndromes and treatment alternatives.

El descubrimiento de nuevos síndromes autoinflamatorios y nuevas mutaciones está avanzando a una velocidad vertiginosa en los últimos años. La segunda parte de la revisión está centrada en el estudio de los síndromes histiocítico-macrofágicos y de los síndromes vasculopáticos, incluyendo al final del texto una tabla con las alternativas terapéuticas de estos síndromes autoinflamatorios y sus mutaciones genéticas.

NOD2-associated pediatric granulomatous arthritis, also known as Blau syndrome or early-onset sarcoidosis, is a hereditary autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mutations in the NACHT domain of NOD2 (CARD15). Like NLRP proteins, NOD2 is an intracytoplasmic receptor involved in innate immune responses to bacteria.1 When stimulated, it triggers the formation of granulomatous lesions through the activation of NF-kB. NLRPs and NODs can interact and feed into each other, giving rise to mixed clinical presentations. Many patients without a family history have de novo NOD2 mutations and incomplete clinical penetrance. Phenotypic expression is highly variable, even within the same families and in patients with the same mutations. Blau syndrome has a similar phenotype to pediatric granulomatous arthritis, with inflammation affecting the eyes, joints, and skin.

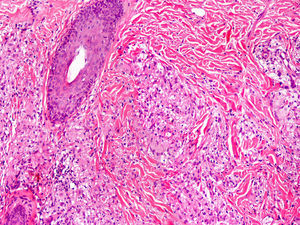

Cutaneous ManifestationsSkin manifestations are among the main manifestations of Blau syndrome. Beginning in early infancy, patients develop asymptomatic, local or generalized erythematous or brownish papules or papules and nodules (Fig. 1) that can present as a lichenoid eruption. The palms and soles may be affected. Other skin manifestations described in NOD2 disorders include ichthyosiform disorders,2 a form of panniculitis that is very similar to erythema nodosum (Fig. 2), and leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The most common cutaneous manifestation, which should raise suspicion of Blau syndrome, is a mild, early-onset generalized eruption of brownish papules that often resolves spontaneously in the first years of life.3 Histopathologic findings are similar to those observed in sarcoidosis, and include noncaseating granulomas with histiocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils (Fig. 3), and giant nucleated cells that are strongly positive when stained with periodic acid-Schiff. Electron microscopy shows so-called comma bodies in epithelioid cells.3

Characteristic associated clinical manifestations include chronic polyarticular synovitis, symmetric hypertrophic tenosynovitis, and recurrent granulomatous anterior uveitis, although panuveitis is more common. Joint involvement is the most common—and severe—noncutaneous manifestation. It begins before the age of 10 years and affects the hands, wrists, ankles, knees, and elbows. The lesions are painless cysts that grow slowly over time and become considerably swollen, although they do not limit mobility until several decades after onset. Granulomatous inflammatory infiltrates formed by giant multinucleated cells are observed in the synovial membrane. Anterior uveitis can be complicated by involvement of the posterior pole, and patients may also develop cataracts, glaucoma, or loss of vision. Ocular involvement is bilateral in most cases.3 The granulomatous infiltrate can also affect, although less frequently, the liver, the salivary glands, the lungs, the kidneys, the nervous system, and the arteries, causing cranial neuropathy, large vessel arteritis, malignant hypertension, and cerebral infarction. The lymph nodes may also be affected, but unlike in sarcoidosis,4 the hilar nodes are not affected, and unlike in other chronic autoinflammatory disorders, secondary amyloidosis is very rare.5

H SyndromeH syndrome is caused by mutations in the SLC29A3 gene, located on chromosome 10q22. The letter H refers to several hallmark features of the syndrome, such as hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, hepatosplenomegaly, hypogonadism, heart anomalies, and hearing loss.

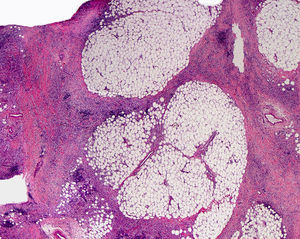

Cutaneous ManifestationsThe progressive appearance of hyperpigmented, hypertrichotic plaques (Fig. 4) and marked sclerosis on the extremities and abdomen is a highly characteristic finding in H syndrome. The lower half of the body is more frequently affected. In most cases the condition begins with hyperpigmentation on the internal surface of the thighs, which then spreads, but generally sparing the knees and buttocks. Some patients also develop ichthyosiform scaling. Skin biopsy shows hyperpigmentation of the basal layer with acanthosis and hyperplasia, similar to that seen in seborrheic keratosis, together with marked fibrosis of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue; the fibrosis is mild in the papillary dermis and much more intense in the subcutis, where it causes progressive obliteration of the fat lobules (Fig. 5). The accompanying infiltrate is mainly composed of numerous, small histiocytes (CD68+, S100+, CD1a−)with clear cytoplasm6 and occasional emperipolesis. Characteristic electron microscopic findings include a distended endoplasmic reticulum and sparse lysosomes.

Associated manifestations in H syndrome include deafness, low stature, flexion contractures, dilated veins in the legs and abdominal wall, heart anomalies, early ischemic cardiomyopathy,7 hepatosplenomegaly, scrotal masses, hypogonadism, delayed puberty, azoospermia, and hyperglycemia/diabetes mellitus.8

Chronic Atypical Neutrophilic Dermatosis With Lipodystrophy and Elevated Temperature SyndromeChronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome is the paradigm of proteasome-immunoproteasome dysfunction disorders.9 Proteasomes are complex intracellular protein structures that break down and remove ubiquitinated protein residues that are no longer useful. Proteasome is present as a constitutive subunit in cells, but when catalytic requirements increase (in response to an infection or physical stimulus), it is replaced by an inducible immunoproteasome subunit. Deficient immunoproteasome assembly or loss of function results in a considerable accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins inside macrophages, triggering major cellular stress and an increased production of type I interferon (IFN) due to the secondary activation of the JAK-kinase signaling pathway. The result is a vicious circle characterized by the continuous formation and accumulation of intracellular protein residues. The main features of CANDLE syndrome are recurrent fever, visceral inflammation, lipodystrophy, and fixed cutaneous lesions that do not tend to resolve spontaneously. They appear during the first year of life, typically within the first few weeks. Genetic studies have shown mutations in several genes that code for different proteasome/immunoproteasome subunits, such as β5i, β1i, β7, and α3. The mutations result in decreased catalytic activity of the immunoproteasome or prevent its assembly. Although the most common mutations in patients with CANDLE syndrome are biallelic PSMB8 mutations, there have been recent reports of monoallelic mutations with a digenic inheritance10 in genes that code for different subunits and of POMP mutations in 1 patient (Table 1).

Genetic Mutations and Treatment Alternatives.

| Mutation | Protein | Treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blau Syndrome | AD and sporadic NOD2/CARD15 | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain–containing protein 2 | NSAIDs Systemic corticosteroids35 Ciclosporin Methotrexate TNF inhibitors35,36 Thalidomide37 IL-1 antagonists5,6,16,34,38 |

| H Syndrome | AR SLC29A3 | hENT349 | Not established Partial remission with systemic corticosteroids and methotrexate |

| CANDLE | PSMB8 PSMB4 PSMB9 PSMA3 POMP | Subunit β5i Subunit β7 Subunit β1i Subunit α3 Proteasome maturation protein | NSAIDs Systemic corticosteroids Ciclosporin, methotrexate TNF inhibitors39 IL-1 antagonists IL-6 antagonists17,39 Baricitinib (JAK1/2 inhibitor)40 Tofacitinib17 |

| Aicardi-Goutières | AR (some cases of AD36) TREX1 RNASEH2 (A/B/C) SAMHD1 ADAR1 IFIH1 | hTREX1 | Systemic corticosteroids Azathioprine Intravenous immunoglobulin Type I anti-interferon41 Inverse transcriptase inhibitors41,42 Mycophenolate mofetil41 |

| Chilblain lupus | AD (and some sporadic cases) TREX1 and SAMHD1 | hTREX1 | Topical and systemic corticosteroids Topical immunomodulators Antimalarials33,43,44 Mycophenolate mofetil44 Calcium antagonists Physical warmup Psychotherapy (if anorexia exists)33 |

| SAVI | AD TMEM173 | STING | JAK-kinase inhibitors44,45 (tofacitinib, ruxolitinib, baricitinib) |

| C1q deficiency | C1q | Immunosuppressants Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation46 Fresh frozen plasma47 | |

| Adenosine desaminase 2 deficiency | AR CECR1 | Adenosine desaminase 2 | Systemic corticosteroids45 Ciclophosphamide45 TNF inhibitors32,48 |

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; CANDLE, chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SAVI, STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

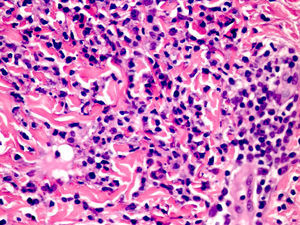

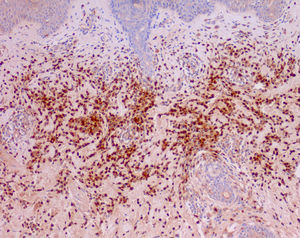

Cutaneous manifestations of CANDLE syndrome consist of annular edematous, erythematous violaceous plaques with elevated borders that mainly affect the trunk (Fig. 6), although they can also affect the extremities (mainly the interphalangeal joints) and the area around the mouth and the eyes, causing persistent violaceous erythema.11 Although these lesions resolve spontaneously, leaving hyperpigmentation or residual ecchymotic macules, they recur with sufficient frequency to be considered a chronic, persistent skin disorder. Histopathologic findings include dense perivascular and interstitial inflammatory infiltrates in the dermis, with occasional involvement of the subcutaneous tissue, absence of vasculitis, and presence of karyorrhexis, albeit inconsistently. The infiltrate is composed of atypical mononuclear myeloid cells with large mottled, long or kidney-shaped nuclei and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm,11 accompanied by a variable number of neutrophils and eosinophils (Fig. 7). Immunohistochemical studies show positive staining for myeloperoxidase, lysozyme, Mac387, CD68 (KP1), and CD16312,13 (Fig. 8) and a double population of myeloid cells and macrophages. Finally, the presence of plasmacytoid CD123+ dendritic cells, which are powerful producers of type I IFN, indicate that this cytokine has a more than significant role in CANDLE syndrome.

CANDLE (chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature) syndrome. Infiltrate of atypical mononuclear myeloid cells with large, mottled nuclei and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm, accompanied by neutrophils and eosinophils (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×40).

Less frequently, patients develop violaceous nodules that leave residual hyperpigmentation, hypertrichosis, acanthosis nigricans, and alopecia areata.14 Progressive lipodystrophy on the face, upper extremities, and trunk is a highly characteristic, defining feature of CANDLE syndrome.

Associated Clinical ManifestationsAccording to reports in the literature, all patients experience frequent and sometimes even daily episodes of high fever (> 30°C) and are also affected by low weight and short stature.15 Associated clinical manifestations include enlarged lymph nodes, hepatosplenomegaly, arthralgia without arthritis, and multiple other inflammatory events, such as chondritis, conjunctivitis, nodular episcleritis, epididymitis, nephritis, otitis, parotiditis, and aseptic meningitis. Patients with CANDLE syndrome may also have dysmorphic features such as a broad nasal bridge, fat lips, and an everted lower lip.15 Laboratory studies typically show elevated acute phase reactants, chronic anemia, elevated liver enzymes, and transient lymphopenia during flares.

Vasculopathy SyndromesWithin the group of vasculopathy syndromes we will discuss interferonopathies and disorders caused by adenosine deaminase 2 (ADA2) deficiency.

Type I InterferonopathiesType I IFNs are cytokines with a key role in the link between the innate and acquired immune system. Viral DNA, which is recognized by the type 1 IFN receptor, activates STING (stimulator of IFN genes)–dependent signaling to produce IFN and other proinflammatory cytokines.16 This increased production of IFN stimulates the immunoproteasome, which activates the JAK-STAT pathway with greater frequency, generating even more IFN and intensifying and perpetuating the immune response and autoinflammatory conditions. In this next section we will look at the most relevant interferonopathies in dermatology and describe their hallmark clinical features.

Aicardi-Goutières SyndromeAicardi-Goutières syndrome is a genetically highly heterogeneous neurodegenerative disorder with a high degree of consanguinity. It is characterized by cerebral and cutaneous involvement. Although mostly transmitted in an autosomal recessive manner, there have been reports of autosomal dominant transmission. Disease-causing mutations have been detected in 7 genes: TREX1, which codes for a 3′-5′ exonuclease, RNASEH2A, RNASEH2B, RNASEH2C, SAMHD1, IFIH1, and ADAR1.17 The mutations cause deficient destruction of viral genetic material, which is needed to downregulate the production of IFN in infected cells. This dysregulation of IFN-α generates proinflammatory situations that trigger secondary vasculitic conditions, such as encephalopathy or acrocyanosis. Although Aicardi-Goutières can be congenital, onset is more common in the first year of life in healthy term infants.

Cutaneous ManifestationsCharacteristic cutaneous manifestations include chilblain-like lesions located mainly on the fingers although they can also affect the feet and ears. They are more common in winter and may be accompanied by acral necrosis. Apart from the better-known cutaneous manifestations of Aicardi-Goutières, such as photosensitivity, acrocyanosis, petechial purpura on the upper half of the trunk and face, swelling of the hands and feet, periungual erythema, nail dystrophy, and cold feet, there have been reports of blueberry muffin baby, which mimics the clinical phenotype of a TORCH-type congenital viral infection in the form of red-bluish generalized macules and papules.18 The histopathologic findings in this last condition are compatible with extramedullary hematopoiesis and include a polymorphous infiltrate in the dermis and the subcutaneous tissue composed predominantly of precursor erythroid and myeloid cells that show positive immunostaining with glycophorin A, myeloperoxidase, peroxidase, CD20, and CD3, confirming, respectively, the presence of erythrocytes, leukocytes, B cells, and T cells.18

Associated Clinical ManifestationsPatients develop severe subacute encephalopathy that stabilizes after a period of progression and is associated with calcification of the basal ganglia, leukodystrophy, progressive microcephaly, and pyramidal-extrapyramidal dysfunction accompanied by epilepsy and aseptic febrile episodes. There have also been reports of chronic arthroplasty with progressive acral contractures and oral mucosal ulcers.19 Laboratory studies show high levels of IFN-α, neopterin, biopterin,20 and lymphocytosis, which is also observed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Elevated IFN-α in CSF is considered a major diagnostic criterion for Aicardi-Goutières syndrome.21 Patients may also present thrombocytopenia, elevated liver enzymes, and in some cases, hyperpolygammaglobulinemia, and Coombs-positive hemolytic anemia. All these conditions have a highly variable clinical expression and none of them are necessary for diagnosis.19

Familial Chilblain LupusFamilial chilblain lupus is a rare familial form of cold-induced cutaneous lupus erythematosus that may be sporadic, or less frequently, hereditary. It is generally caused by a mutation in TREX1. TREX1 is the major intracellular repair exonuclease and its deficiency leads to the accumulation of nucleic acids and the activation of the innate immune system accompanied by an increase in INF that favors the development of autoimmunity.6

Cutaneous ManifestationsStarting from an early age, children develop violaceous perniotic plaques at acral sites that may ulcerate and are clinically and histologically very similar to lesions seen in Aicardi-Goutières syndrome. Histology shows interface dermatitis with basal cell vacuolization accompanied by a dense perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis, together with mucin in the reticular dermis. Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) shows basal deposits of immunoglobulin (Ig) M, IgA, and C3 and perivascular deposits of C3 and fibrinogen.22,23

Associated Clinical ManifestationsPatients occasionally develop systemic manifestations such as arthralgia and nonerosive arthritis. Laboratory studies show mild pancytopenia, hypergammaglobulinemia, rheumatoid factor, antinuclear antibodies (ANAs), and anti-Ro/SSA antibodies.23 Cryoglobulins and cold agglutinins are negative. Up to 20% of patients develop systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)24 and there is a lack of consensus on the association with anorexia.

STING-associated Vasculopathy With Onset in InfancyAs previously explained, sensing of viral RNA and DNA is the main biological trigger for the activation of STING, which is a transmembrane protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum that induces the production of IFN. STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in childhood is due to gain-of-function mutations in STING.25,26 The protein is widely expressed in endothelial and alveolar cells. STING hyperfunction causes inflammation in endothelial cells, generating vaso-occlusive phenomena and pulmonary lesions, possibly due to the activation of macrophages or alveolar pneumocytes. The release of IFN triggers a positive feedback loop, as it directly triggers the transcription of other proinflammatory cytokines and activates JAK-kinases, which, in turn trigger the phosphorylation and dimerization of STAT1/STAT2, which initiate the transcription of IFN genes.

Cutaneous ManifestationsThe clinical manifestations begin in the first year of life as a telangiectatic pustular and/or bullous rash located at acral sites and on the cheek. This eruption then progresses, mostly in response to exposure to cold, to acral violaceous nodules and plaques that become necrotic in most cases and can affect extensive areas, causing significant tissue loss. Characteristic findings are capillary tortuosity of the nail bed, and telangiectasias on the nose, cheeks, extremities, and hard palate. Other possible manifestations are perforation of the nasal septum, dystrophic nails, resorption of the distal phalanges, and digital gangrene requiring amputation.26 Histopathologic findings include a dense, predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in the dermis with leukocytoclastic vasculitis and thrombotic microangiopathy of the small dermal vessels,26 some of which may contain deposits of IgM, C3, and fibrin.

Associated Clinical ManifestationsPatients with STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy have recurrent episodes of low-grade fever and may also experience delayed growth, severe lung disease with enlarged hilar or paratracheal lymph nodes, interstitial fibrosis, and emphysematous changes caused by a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate.27 The laboratory study shows increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP), and on occasions, ANA, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and antiphospholipid antibodies, which tend to normalize with time.

C1q DeficiencyC1q is a protein that forms part of the C1 complex of the complement system. In addition to its role in activating the complement cascade, it inhibits the production of IFN by plasmacytoid dendritic cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Loss-of-function C1q mutations result in a phenotype similar to that seen in SLE in 90% of cases.28

Cutaneous ManifestationsThe cutaneous manifestations of C1q deficiency include butterfly rash on the face, discoid lupus–type lesions, and Raynaud phenomenon, similar to that seen in SLE.29

Associated Clinical ManifestationsExtracutaneous manifestations of C1q deficiency include segmental mesangial glomerulonephritis (which differs from the typical nephritis seen in SLE), neurological symptoms, and serious recurrent infections caused by deficient functioning of the classic complement pathway. Plasma levels of CH50 and C1q are practically inexistent, contrasting with C2, C4, and C1 inhibitor levels, which are normal or elevated. ANAs, rheumatoid factor, and anti-Smith antibodies are positive. Biopsy of lesions shows basal layer vacuolization, while DIF shows deposits of IgG, IgM, IgA, and C3. The clinical similarities with SLE combined with the presence of clinical features of immunodeficiency are highly suggestive of complement factor deficiency.

ADA2 DeficiencyADA2 deficiency is associated with nonspecific clinical manifestations that overlap with features of polyarteritis nodosa, with necrotizing vasculopathy of the small and medium vessels and livedo reticularis. There is a strong familial predisposition and the condition has accordingly also been called familial polyarteritis nodosa. Low blood levels of ADA2 have been linked to endothelial alterations and greater activation of macrophages, situations that probably cause vasculitis and cerebrovascular accidents.30,31 The clinical manifestations are highly variable, even in families carrying the same mutations, particularly in terms of age of onset, organs affected, and severity of organ involvement.32

Cutaneous ManifestationsTypical clinical manifestations of ADA2 deficiency include changes associated with poor arterial flow, such as livedo reticularis, Raynaud phenomenon, ischemia, and digital necrosis. Biopsy of lesions shows periarteritis, fibrinoid necrosis, and destruction of the elastic lamina of the cutaneous arterioles. There may also be leukocytoclastic vasculitis and panniculitis.

Associated Clinical ManifestationsAdditional manifestations include febrile episodes and frequent aneurysms in the renal, mesenteric, and coronary arteries. Ischemia can cause renal, gastrointestinal, genital, musculoskeletal, cardiovascular, and neurologic manifestations. Of particular note are renal hypertension and a high risk of cerebral ictus during childhood.31

Management of Autoinflammatory SyndromesA growing understanding of the genetic mutations involved in the syndromes described in this review (Table 2) is contributing to the identification of more and more cases and the improvement of patient quality of life. Management of these disorders is closely related to control of the associated immune response. Accordingly, many of the syndromes have a specific treatment or benefit from the blockage of certain proinflammatory molecules (Table 1). Treatments used to date include TNF inhibitors and IL-1 antagonists. The favorable safety and efficacy profile of IL-1 antagonists, such as anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist), rilonacept (dimeric fusion protein), and canakinumab (a fully humanized monoclonal antibody that specifically targets IL-1β), in the treatment of cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes and deficiency of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist has prompted the use of these drugs in other autoinflammatory disorders, such as periodic fever disorders and immune dysregulation disorders, including Still disease, Behçet syndrome, and Schnitzler disease. In addition, the fact that the accumulation of metabolic substrates, such as monosodium urate, cholesterol, and glucose, can stimulate the NLRP3 inflammasome due to metabolic stress and the secondary role of IL-1 could justify the use of IL-1 antagonists in highly prevalent diseases, such as gout, diabetes mellitus, and heart disease.33,34 The use of baricitinib (JAK1/2 inhibitor) in the treatment CANDLE syndrome, for example, is producing promising results.

Summary of Main Autoinflammatory Disorders and Mutations.

| Disease | Heredity | Genetic mutation | Mutated protein |

|---|---|---|---|

| Familial Mediterranean fever | AR | MEFV | Pyrin |

| Mevalonate kinase deficiency (HyperIgD syndrome) | AR | MVK | Mevalonate kinase |

| Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) | AD | TNFRSF1A | TNFR (TNF receptor) superfamily IA |

| Periodic fever with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis syndrome (PFAPA) | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| PLCG2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation (PLAID)/Autoinflammation and PLCG2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation (APLAID) | AD | PLCG2 | Phospholipase CG2 (PLCG2) |

| Familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome | AD | NLRP3/CIAS1 | Cryopyrin |

| Muckle-Wells syndrome | AD | NLRP3/CIAS1 | Cryopyrin |

| Neonatal onset multisystemic inflammatory disorder (NOMID) | AD | NLRP3/CIAS1 | Cryopyrin |

| Deficiency of the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) | AR | IL-1RN | Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist |

| Deficiency of the interleukin-36 receptor antagonist (DITRA) | AR | IL-36RN | Interleukin-36 receptor antagonist |

| Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne syndrome (PAPA) | AD | PSTPIP1/CD2BP1 | Proline/serine/threonine phosphatase-interacting protein 1 |

| Majeed syndrome | AR | LPIN2 | Lipin 2 |

| Blau syndrome | AD | NOD2/CARD15 | Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain protein 2 |

| H syndrome | AR | SLC29A3 | Human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 3 (hENT3) |

| Chronic atypical neutrophilic dermatosis with lipodystrophy and elevated temperature (CANDLE) syndrome | AR | PSMB8 | i-proteasome β5i subunit |

| PSMB4 | Proteasome β7 subunit | ||

| PSMB9 | i-proteasome β1i subunit | ||

| PSMA3 | Preoteasome α3 subunit | ||

| POMP | Proteasome maturation protein | ||

| Aicardi–Goutières syndrome | AR (rarely AD) | TREX1 (AGS1) | 3-prime repair exonuclease 1 |

| RNASEH2 (AGS 2-4) | RNASEH2 endonuclease complex | ||

| SAMHD1 (AGS5) | SAM domain–and HD domain–containing protein 1 | ||

| ADAR1 (AGS6) | RNA-specific adenosine deaminase 1 | ||

| IFIH1 (AGS7) | interferon-induced helicase c domain-containing protein 1 | ||

| Familial chilblain lupus | AD | TREX1 (AGS1) | 3-prime repair exonuclease 1 |

| SAMHD1 (AGS5) | SAM domain- and HD domain containing protein 1 | ||

| STING-associated vasculopathy with onset in infancy (SAVI) | AD | TMEM173 | Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) |

| Deficiency of adenosine deaminase 2 (DADA2) | AR | CECR1 | Adenosine deaminase 2 |

Abbreviations: AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive.

The authors declare that no tests were carried out in humans or animals for the purpose of this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Hernández-Ostiz S, Xirotagaros G, Prieto-Torres L, Noguera-Morel L, Torrelo A. Enfermedades autoinflamatorias en dermatología pediátrica. Parte 2: síndromes histiocítico-macrofágicos y síndromes vasculopáticos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:620–629.