Chronic recurrent granulomatous processes in the anogenital area present with ulcers, fissures, and lymphedema; histopathology reveals nonnecrotizing granulomatous inflammation. Crohn disease is the most common etiologic factor, but cases in which no underlying cause is evident have been grouped under the term anogenital granulomatosis.1

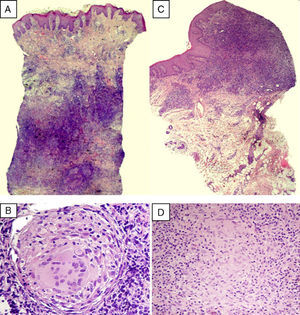

The first case we report is that of a 52-year-old woman with excrescent lesions that had a pseudocondylomatous appearance and fissures in the gluteal cleft that had started 6 months earlier. The lesions were excised but she did not return until 5 years later, when she sought care for chronic recurrent vulvar and perineal lesions. She had ulcers, marked edema of the vulva, longitudinal fissures in the folds, and indurated plaques that were excrescent in the gluteal cleft (Fig. 1). Histopathology of both the vulvar and the perianal areas revealed a lymphocytic infiltrate in the reticular dermis with nonnecrotizing granulomas consisting of multinucleated giant cells (Fig. 2A and B). Additional tests, including complete blood count, biochemistry, chest radiograph, and cultures yielded no findings, except for an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 52mm/h. A colonoscopy with colorectal biopsies ruled out inflammatory bowel disease. The patient was treated with topical corticosteroids, salicylates, and oral corticosteroids; the lesions responded fully to the last treatment but recurred when they were suspended. She was subsequently treated with adalimumab (40mg/15d) but showed no response after 4 months. Fifteen years after the initial episode the patient had not developed systemic symptoms.

(A) Lymphocytic infiltrate occupying the reticular dermis, showing granulomatous structures without central necrosis (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×12.5). (B) Detail of a granuloma composed of multinucleated giant cells and epithelioid cells and surrounded by lymphocytes (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×400). (C) Dense lymphocytic infiltrate occupying a mucous membrane (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×40). (D) At higher magnification, epithelioid cells are seen forming nonnecrotizing granulomas (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×400).

The second case is that of a 51-year-old woman who presented with painful erosions and vulvar edema dating from 5 months earlier. For 6 years she had also had recurrent perianal suppurative plaques and fissures that had been diagnosed as hidradenitis suppurativa. Physical examination revealed the granulomatous appearance of the vulvar mucosa, erosions on the inside of the labia minora (Fig. 3), and longitudinal fissures in the gluteal cleft. Two vulvar biopsies revealed a dense lymphocytic infiltrate of epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells forming granulomas without central necrosis (Fig. 2C and D). Additional tests (complete blood count, biochemistry, cultures, and chest radiograph) were normal or negative, except for a slightly elevated ESR of 25mm/h. Crohn disease was ruled out after colonoscopy with biopsies. The patient had no systemic symptoms during the 18 months of follow-up and responded partially to treatment with oral corticosteroids but showed no response to salicylates or to adalimumab (40mg/15d), which was therefore suspended after 3 months.

The differential diagnosis of chronic granulomatous diseases in the perineum includes extraintestinal Crohn disease, although this condition is unlikely in the absence of intestinal symptoms or perianal fistulas and with normal colonoscopy.2 Other possible differential diagnoses are shown in Table 1. In view of the clinical presentation, the first diagnostic steps should be biopsy to obtain a specimen for histology (on the basis of special stains and cultures for fungi, bacteria, and mycobacteria). Additional tests useful to rule out underlying causes include complete blood count, biochemistry, iron profile, ESR, angiotensin-converting enzyme levels, serology for syphilis, and chest radiograph. Colonoscopy is recommended, even in the absence of digestive symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis of Anogenital Granulomatosis.

| Noninfectious Causes | Infectious Causes |

| Crohn disease | Tuberculosis |

| Sarcoidosis | Lymphogranuloma venereum |

| Foreign body granuloma | Granuloma inguinale |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | Syphilis |

| Behçet disease | Leprosy |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Deep mycoses |

| Lymphoproliferative diseases | |

| Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome |

Chronic genital granulomatosis without direct communication with the gastrointestinal tract can be observed in metastatic Crohn disease. This condition is the least common cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and consists of skin lesions separated from the digestive tract by healthy skin. It usually affects women between the second and fourth decades of life and can appear anywhere, including on the genitals, although the lower limbs are the most frequent location.3 Clinical manifestations in the genital region are similar to those observed in our patients.4 Lesions are associated with involvement of the colon or rectum5 but usually do not follow a course that runs parallel to the intestinal disease. Chronic genital granulomatosis is associated with long-standing intestinal Crohn disease in 80% of cases.3,6 When the granulomatous process presents first, intestinal involvement usually develops within 4 months to 2 years. The literature offers at least 5 cases3 of cutaneous Crohn disease in the absence of previously recognized intestinal disease, which did not appear during follow-up either. Some authors nonetheless recommend reserving this diagnosis for cases in which intestinal involvement has been demonstrated.7

Orofacial granulomatosis or cheilitis granulomatosa, considered a monosymptomatic form of Melkersson–Rosenthal syndrome, shares some of the clinical and histological features of the anogenital granulomatosis in our 2 cases. Cheilitis granulomatosa presents as persistent and recurrent labial swelling; nonnecrotizing granulomas are sometimes associated with ulceration and gingival hyperplasia or cobblestoning. Anogenital granulomatosis has been suggested to be the genital equivalent of cheilitis granulomatosa2 and although the co-occurrence of these 2 conditions in the same patient is rare, it has been reported.7 In 10%–48% of cases cheilitis granulomatosa and intestinal Crohn disease are associated.8

The term anogenital granulomatosis1 was introduced in 2003 to identify these chronic recurrent conditions with characteristic clinical and histopathologic features that may have different causes. This clinical entity is a unifying concept for others used in the literature (chronic hypertrophic vulvitis, vulvitis granulomatosa, chronic edema of the vulva, Melkersson–Rosenthal vulvitis and anoperineitis granulomatosa) and is especially useful for cases of unknown etiology and those highly suggestive of metastatic Crohn disease in the absence of established intestinal disease.

Therapeutic management of this condition is difficult and there is no set protocol to follow because of the lack of case series and randomized trials. Suggested treatments have obtained mixed and sometimes unsatisfactory results marked by frequent relapse after treatment is discontinued. The reported options include topical, intralesional, and oral corticosteroids,7 salicylates, antibiotics9 such as metronidazole5,10 and ciprofloxacin,4 and immunosuppressants such as azathioprine and ciclosporin.1,3 More recently, anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibodies such as infliximab and adalimumab have given good results.1

We have reported 2 cases of idiopathic anogenital granulomatosis in which possible underlying causes were ruled out and no associated systemic symptoms developed even after years of follow-up.

Please cite this article as: Villar M, Petiti G, Guerra A, Vanaclocha F. Granulomatosis anogenitales. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:76–79.