The value of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) undertaken to identify an association between an intervention and an outcome is determined by their quality and scientific rigor.

ObjectiveTo assess the methodological quality of RCTs published in Spanish-language dermatology journals.

MethodsBy way of a systematic manual search, we identified all the RCTs in journals published in Spain and Latin America between 1997 (the year in which the CONSORT statement was published) and 2012. Risk of bias was evaluated for each RCT by assessing the following domains: randomization sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of patients and those assessing outcomes, missing data, and patient follow-up. Source of funding and conflict of interest statements, if any, were recorded for each study.

ResultsThe search identified 70 RCTs published in 21 journals. Most of the RCTs had a high risk of bias, primarily because of gaps in the reporting of important methodological aspects. The source of funding was reported in only 15 studies.

Discussion and conclusionsIn spite of the considerable number of Spanish and Latin American journals, few RCTs have been published in the 15 years analyzed. Most of the RCTs published had serious defects in that the authors omitted methodological information essential to any evaluation of the quality of the trial and failed to report sources of funding or possible conflicts of interest for the authors involved. Authors of experimental clinical research in dermatology published in Spain and Latin America need to substantially improve both the design of their trials and the reporting of results.

La relevancia del ensayo controlado con asignación aleatoria (ECA) para determinar si existe una asociación entre una intervención y un desenlace está determinada por su calidad y rigor científico.

ObjetivoEvaluar la calidad metodológica de los ECA publicados en revistas dermatológicas en español.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda manual y sistemática de los ECA publicados en las revistas de Dermatología españolas y latinoamericanas entre 1997 (publicación de los criterios CONSORT) y 2012. Se determinó el riesgo de sesgo de cada ECA, evaluando los siguientes dominios: generación de la secuencia aleatoria, ocultamiento de la asignación, cegamiento de los pacientes/evaluadores de desenlaces, datos faltantes y seguimiento de pacientes. Se identificaron la fuente de financiación de los estudios y el reporte de conflictos de interés.

ResultadosSe identificaron 70 ECA publicadas en 21 revistas. La mayoría de los ECA tuvo un alto riesgo de sesgo, principalmente por falta de reporte de los aspectos metodológicos importantes. Solo 15 estudios declararon fuentes de financiación.

Discusión y conclusionesA pesar del número considerable de revistas existentes en España y Latinoamérica, en los 15 años estudiados se han publicado pocos ECA. La mayoría de los estudios presentó problemas de calidad importantes, al carecer de información metodológica que permitiera evaluar su calidad y a las falencias en el reporte de las fuentes de financiación y de los conflictos de interés de los autores. La investigación clínica experimental dermatológica que se publica en Ibero-Latinoamérica debe mejorar ostensiblemente tanto en su diseño como en su reporte de resultados.

The randomized controlled trial (RCT) is the most rigorous type of methodological design and the best way of determining whether a cause-effect relation exists between an intervention and the result or outcome being assessed. RCTs also provide the raw material for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. However, the value of such studies depends on the quality and methodological rigor of their design and implementation.

In recent decades, the field of dermatology has seen a substantial increase in experimental clinical research. However, this upturn in the volume of research has not been accompanied by a corresponding improvement in trial design and methodology. Several studies have reported that the RCTs published in the dermatology literature tend to fall below acceptable standards.1–4

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement was first published in 1996 to improve the quality of reporting of clinical trials worldwide.5 The CONSORT statement includes a checklist designed to improve the reporting of RCTs, which also, indirectly, throws light on the study's quality and scientific rigor.

An improvement in the scientific quality and reporting of RCTs might have been expected following the implementation of CONSORT and the publication of the Medical Research Council Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice in Clinical Trials (available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/ucm073122.pdf and http://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/good-clinical-practice-in-clinical-trials/). However, the evidence reveals the continued presence after 1997 of serious flaws in the design and reporting of clinical trials.6 The problem has also been observed in trials in the Spanish-language dermatology literature published after 1997. A study carried out in Spain found that only 6 (25%) of the 24 clinical trials found in the dermatology journal with the highest impact in that country—Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas—were classified as being of high quality.3

In this context, the aim of the present study was to assess the methodological quality of the experimental clinical research in dermatology published in Spanish to facilitate an analysis of the strengths of these studies and the challenges that must be overcome. We analyzed the RCTs identified by a recent study that handsearched Spanish-language dermatology journals.7

The present study complements that work by analyzing the methodological quality of the RCTs published between 1997 and 2012 using the appropriate Cochrane Collaboration tools and a review of the reporting of conflicts of interest and funding sources.

ObjectiveTo assess the methodological quality of the RCTs published in Spanish-language dermatology journals between 1997 and 2012.

Materials and MethodsJournal Identification: Manual and Electronic SearchThe methodology used to identify the RCTs published in Spanish-language dermatology journals has already been described in an earlier article.7

In a preliminary phase, all eligible journals were identified in the framework of a project led by the Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre (IbCC) in Barcelona, Spain. Using the IbCC protocol, journals were located through the following search engines and databases: MEDLINE (through PubMED), EMBASE, LILACS (Latin American Index of Scientific and Technical Literature), SciELO, Periódica, Latindex, Índice Médico Español, Catálogo Nacional de Publicaciones Periódicas en Ciencias de la Salud Españolas (C-17), as well as in other catalogues of health sciences publications in Spain. This initial search strategy was then complemented by a search of the Spanish health sciences indexes (IBECS and IMBIOMED), by free-text Internet searches using Google, by contacting the Dermatology societies in each of the countries studied, and through direct contact with dermatologists.

Each journal identified was then handsearched to identify all the RCTs published. This retrospective review was carried out in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration's manual for handsearching archives and identifying clinical trials (available from http://www.cochrane.es/∼cochrane/?q=es/node/140). Each journal was searched from 2012 back to the first issue published (provided full texts were still available).7

In addition to handsearching for RCTs, we also conducted an electronic search of MEDLINE (using PubMed),EMBASE, LILACS and IBECS, as well as the search engines of the Biblioteca Virtual en Salud hosted by the Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information (Bireme), the Pan American Health Organization, and the World Health Organization.

Data ExtractionA database was created to store each of the RCTs retrieved, to facilitate the handsearch of each journal, and to ensure that data was gathered and processed in an organized and systematic manner. We also identified journals specifying CONSORT reporting in their instructions to authors and journals indexed on MEDLINE or EMBASE.

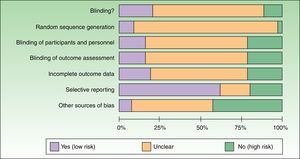

Analysis of Quality and Risk of BiasOnly RCTs published between 1997 (the first year the CONSORT statement was implemented) and 2012 were included in the review of scientific rigor and methodological quality. The appraisal was performed twice, and any resulting discrepancies were resolved by a third assessor. The review was carried out using the Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias (high/medium/low).8 This tool assesses the methodological aspects of clinical trials, including sequence generation, concealment of the sequence of patient allocation to the different arms of the study, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, incomplete data, and patient follow-up. The reviewer assesses each one of these domains and assigns one of the following answers: “yes”, “no”, or “unclear/not reported”.

Studies were categorized as having a “high risk of bias” if they had 1 flaw that affected the generation of the allocation sequence or had more than 1 flaw affecting any of the other methodological aspects analyzed. If the necessary information was unavailable, the study was categorized as “unclear risk/not reported”. The results of the assessment and scoring of these methodological aspects were recorded using version 5.2 of the application Review Manager (Copenhagen, the Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012). Information on sources of funding and the reporting of potential conflicts of interest on the part of authors were also logged.

Statistical AnalysisDescriptive statistics of the resulting information were compiled, using univariate analysis to determine the frequencies of the variables. Appropriate summary measures were calculated for the continuous variables. Absolute and relative frequencies and their percentages were determined for qualitative variables. When appropriate, the confidence interval was calculated for proportions. The data were recorded on Review Manager and also in an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 2010). The software package SPSS (version 19, IBM) was used to analyze the data.

ResultsOf the 28 journals that fulfilled the criteria for eligibility, 21 were eventually included in the study: 5 from Spain and 16 from Latin American countries. Of these 21 journals only Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas is currently indexed on both MEDLINE and EMBASE. Four others are indexed on EMBASE: Dermatología Revista Mexicana, Argentina de Dermatología, Medicina Cutánea Ibero Latinoamericana and Piel.7

The total number of journals included and excluded, and the reasons for the choices made have been described in an earlier article (Fig. 1).7

Flow chart showing the process used to select dermatology journals according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Source: Sanclemente G, Pardo H, Sánchez S, Bonfill X. Identificación de ensayos clínicos en revistas dermatológicas publicadas en español. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:415-422).

Seventy RCTs published between 1997 and 2012 were identified in the 21 journals studied: 73% (51) in the 16 Latin American journals and 27% (19) in the 5 Spanish journals (Table 1) (Appendix 1). The Latin American journals that published the largest number of RCTs were Dermatología Revista Mexicana (16), Dermatología Peruana (9), and Revista Chilena de Dermatología (5) (Table 1). The Spanish journals that published the most RCTs were Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas and Piel, with 8 each (Table 1).

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) Identified in Spanish and Latin American Dermatology Journals.

| Journal Name | Periods Not Assessed Because No Copies (Print or Electronic) Available | Number of RCTs Identified | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dermatología Revista Mexicana | – | 16 |

| 2 | Dermatología Peruana | – | 9 |

| 3 | Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas | – | 8 |

| 4 | Piel | – | 8 |

| 5 | Revista Chilena de Dermatología | – | 5 |

| 6 | Dermatología Cosmética, Médica Y Quirúrgica | – | 4 |

| 7 | Revista del Centro Dermatológico Pascua | – | 4 |

| 8 | Revista Asociación Colombiana de Dermatología | – | 4 |

| 9 | Medicina Cutánea Ibero-Latino-Americana | – | 3 |

| 10 | Folia Dermatológica Peruana | – | 2 |

| 11 | Dermatología Argentina | – | 2 |

| 12 | Folia Dermatológica Cubana | – | 2 |

| 13 | Dermatología Venezolana | – | 2 |

| 14 | Revista Argentina de Dermatología | – | 1 |

| 15 | Archivos Argentinos de Dermatología | – | 0 |

| 16 | Actas de Dermatología y Dermatopatología | – | 0 |

| 17 | Revista Dominicana de Dermatología | 1997-2009 | 0 |

| 18 | Revista Sociedad Ecuatoriana de Dermatología | 1997-2002, 2005, 2008, 2009, 2011, 2012 | 0 |

| 19 | Gaceta Dermatológica Ecuatoriana | 1999-2012 | 0 |

| 20 | Actualidad Dermatológica | – | 0 |

| 21 | Revista Fontilles | 1997-2002 | 0 |

| Total | 70 |

Most of the trials reviewed were classified as having a high risk of bias because the authors failed to report the information needed to assess the quality and methodological rigor of the trial (Table 2). A small percentage of trials had a low risk of bias in the domains assessed (Table 2) (Fig. 2).

Assessment of Methodological Aspects of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) Published in Spanish and Latin American Dermatology Journals.

| Methodological Aspect | No. (%) | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation concealment | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 48 (68.6) | 57.73%-79.47% |

| Yes | 14 (20) | 10.63%-29.37% |

| No | 8 (11.4) | 3.95%-18.85% |

| Sequence generation | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 62 (88.6) | 81.15%-96.05% |

| Yes | 6 (8.6) | 2.03%-15.17% |

| No | 2 (2.8) | –1.06%-6.66% |

| Blinding of participants/personnel | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 44 (62.8) | 51.48%-74.12% |

| Yes | 11 (15.7) | 7.18%-24.22% |

| No | 15 (21.5) | 11.88%-31.12% |

| Blinding of outcome assessors | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 44 (62.8) | 51.48%-74.12% |

| Yes | 11 (15.7) | 7.18%-24.22% |

| No | 15 (21.5) | 11.88%-31.12% |

| Incomplete outcome data | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 42 (60) | 48.52%-71.48% |

| Yes | 13 (18.5) | 9.4%-27.6% |

| No | 15 (21.5) | 11.88%-31.12% |

| Selective outcome reporting | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 12 (17.2) | 8.36%-26.04% |

| No | 44 (62.8) | 51.48%-74.12% |

| Yes | 14 (20) | 10.63%-29.37% |

| Other sources of bias | ||

| Unclear/Not reported | 35 (50) | 38.29%-61.71% |

| No | 5 (7, 15, 8) | 7.26%-24.34% |

| Yes | 30 (42.9) | 31.31%-54.49% |

| Funding sources | ||

| Not reported | 55 (78.6) | 68.99%-88.21% |

| Reported | 15 (21.4) | 11.79%-31.01% |

| Conflicts of Interest | ||

| Not reported | 65 (92.8) | 86.74%-98.86% |

| Reported | 5 (7.2) | 1.14%-13.26% |

The authors of 15 RCTs reported sources of funding and only 2 did so in the required manner (Ramirez-Bosca et al. and Pinto et al.) (Appendix 1). The authors of 5 studies reported conflicts of interest, but only 1 of these reports conformed to accepted standards (Ramirez-Bosca et al.) (Appendix 1). Of all the journals assessed, only Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas,since 2008, requires authors to report trials in accordance with the CONSORT guidelines; however, none of the authors reported in the body of the article whether or not the CONSORT checklist had been used to guide the reporting of the study.

Figure 2 is a summary of the risk of bias for the RCTs identified.

DiscussionThe objective of this study was to assess the methodological quality of the RCTs published in Spanish-language dermatology journals between 1997 and 2012. Our findings show that the risk of bias was high in the clinical trials published in the Spanish-language dermatology literature in that period, primarily because authors failed to report on important methodological aspects of their work. Although this shortcoming had already been described in earlier studies focusing on specific dermatology journals in Spanish,9 this is the first comprehensive analysis that covers all the dermatology journals publishing RCTs in Spain and Latin America. Our findings are similar to those of authors who studied RCTs in the English-language dermatology literature or RCTs on diseases such as perioral dermatitis and atopic dermatitis.4,10,11

The presence of such flaws in RCTs is of particular concern because this type of study is considered to be a gold standard for the assessment of the efficacy and safety of an intervention. Consequently, the implication is that dermatological practice today (at least that predicated on evidence from the studies assessed) may be based on information gathered in a non-systematic manner or on clinical experiments lacking control groups.12 We also detected a mismatch between the outcomes typically assessed and those that might interest patients. For example, many dermatology studies now incorporate variables relating to quality-of life because of the considerable interest of patients in this outcome in relation to dermatological treatments.13–15 However, it is striking that quality-of-life was assessed in only 1 of the 70 RCTs identified.

The methodological aspects least often reported were random sequence generation and allocation concealment; authors also failed to report on sources of funding and possible conflicts of interest. Our findings, which are similar to those observed by other authors in journals that endorse CONSORT reporting as well as in those that do not,6,16,17 highlight shortcomings in the scientific rigor with which the RCTs were designed and reported. In the future, experimental clinical research published in Spain and Latin America in the field of dermatology needs to be considerably improved both in the design and the reporting of results (endorsement and application of the CONSORT guidelines).

The starting point for an unbiased study is the use of a mechanism that ensures that all the patients have the same probability of belonging to one group or the other, and that adequate concealment of the allocation sequence prevents selective recruitment of patients according to prognostic factors (guidelines available from http://handbook.cochrane.org/). In fact, it has been shown that inadequate random sequence generation in an RCT can result in an overestimation of the effect of the treatment of up to 12%,18 while inadequate allocation concealment may increase the effect up to 18%. Furthermore, the fact that a clinical experiment is classified as randomized does not, in and of itself, guarantee that the study fulfils the methodological standards associated with this type of study.19

The only journal included in this study that requires authors to comply with the CONSORT statement when reporting clinical trials is Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas. This endorsement may explain the higher methodological quality of the RCTs published recently by that journal. However, it has been observed that, despite improvements in reporting of RCTs when this tool is used, the completeness of reporting of trials continues to be suboptimal in terms of ensuring a better quality of study.6

Of note is the fact that almost none of the trials identified provided any information on sources of funding or conflicts of interest. Complete reporting of both of these aspects is essential since the results of the trial may be affected by the personal interests of the researcher or the funder of the study (very often a pharmaceutical company).20–22 Transparency is important because it is common in the dermatology literature to find selective reporting of endpoints, a practice which in most cases leads to the overestimation of positive outcomes.23 This practice may be associated with the presence of conflicts of interest. Therefore, in the future careful assessment of these characteristics will be essential in the studies published in Spanish-language dermatology journals.24

One of the principal strengths of the present study was that 21 dermatology journals published in Spanish were handsearched to identify RCTs. The clinical trials identified will shortly be included in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), making them available for future systematic reviews and other summary documents. As reported by the earlier article, which identified the RCTs7 analyzed in the present study, finding 70 RCTs and retrieving the full texts of those articles would have been impossible through an electronic search because only 1 journal is indexed on MEDLINE (Actas Dermo-Sifiliográficas) and only 4 are indexed on EMBASE7 (Dermatología Revista Mexicana, Revista Argentina de Dermatología, Medicina Cutánea Ibero Latinoamericana and Piel). Another strength of the present study was the duplicate analysis of the quality of the RCTs and the use of internationally-recognized and validated Cochrane tools. (Available from: http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_8/8_assessing_risk_of_bias_in_included_studies.htm).

The main limitation of this study was the impossibility of assessing all the volumes and issues of 3 journals: 2 published in Ecuador and 1 published in the Dominican Republic. However, it is unlikely that our results would have differed significantly with a complete analysis of these 3 journals since no RCTs were found in the issues we were able to review. Furthermore, none of those journals have endorsed the CONSORT statement or require its use. Another limitation was the variability of the endpoints and the way these were measured in the RCTs identified. This variability led to a high level of heterogeneity among the studies, making it difficult to quantitatively summarize the results in a meta-analysis

In conclusion, the risk of bias of the clinical trials published in Spanish-language dermatology journals between 1997 and 2012 was high, mainly because the study reports provided insufficient information on which to base any assessment of the quality and methodological rigor of the studies. Moreover, in many cases the authors failed to report on sources of funding and possible conflicts of interest. Complete reporting of all methodological aspects of trials is recommended, as this would allow readers to detect possible sources of bias and design flaws. A complete description of the study is important because it facilitates proper analysis of the evidence and because it ensures that a trial is not classified as having a high risk of bias solely because of omissions in the information provided. Complete reporting will benefit patients—the foundation of evidence-based dermatological practice—and will contribute to more effective decision-taking in this field of practice. Finally, and as a future strategy, we plan to contact the publishers of the dermatology journals analyzed with a view to standardizing prospective tools for the identification of the RCTs published in their journals. The implementation of such a system will facilitate continual updating of this work, thereby obviating the need to repeat the manual search in the future.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals during the course of this study.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

FundingGrupo de Investigación Dermatológica (GRID), Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

We would like to acknowledge with thanks the work of all the students enrolled in the public health Masters degree program at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona for their help in identifying the dermatology journals. Thanks are also due to Ivan Solà of the Iberoamerican Cochrane Centre for his advice on the search process and his critical reading of the manuscript. We would also like to express our gratitude to Elizabeth Dussan and Nelly Pinzón (Colombian Association of Dermatology), to Karina Vielma and Dr. María Isabel Herane (Chilean Dermatology Society), to Dr. Alexandro Bonifax (Revista Dermatología Mexicana), to Dr. Roberto Arenas and Dr. Jorge Ocampo-Candiani (Revista Dermatología Cosmética Médica y Quirúrgica), and to Dr. Edgardo Chouela for their help in the search and in sending full texts of the articles we requested.

Dr. Gloria Sanclemente is a PhD candidate in the department of pediatrics, obstetrics, gynecology, and preventive medicine of the Universitat Autónoma de Barcelona, Spain. This study was carried out with the help of the Group of Investigative Dermatology (GRID) of the Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia.

| 1. Alacán PL, Lemus CO, Lima AAS, Moredo RE. Eficacia de podofilina, ácido tricloroacético y criocirugía en el tratamiento de las verrugas genitales externas. Folia Dermatol Cub. 2012;6(3) |

| 2. Alfaro-Orozco LP, Alcalá-Pérez D, Navarrete-Franco G, González- González M, Peralta-Pedrero ML. Efectividad de la solución de Jessner más ácido tricloroacético al 35% vs 5-fluorouracilo al 5% en queratosis actínicas faciales múltiples. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2012;56:38-46 |

| 3. Alfonso-Trujillo I, Acosta D, Álvarez M, Pernas A, Toledo MC, Rodríguez MA. Condiloma acuminado: eficacia terapéutica comparativa entre el ácido tricloroacético solo y el ácido tricloroacético asociado al levamisol. Dermatol Perú. 2009;19: 114-121. |

| 4. Alfonso-Trujillo I, Acosta Medina D, Álvarez Labrada M, Rubén Quesada M, Rodríguez García MA. Condiloma acuminado: eficacia terapéutica comparativa entre la podofilina sola y la podofilina combinada con levamisol. Piel. 2009;24:354-359. |

| 5. Alfonso-Trujillo I, Acosta-Medina D, Álvarez-Labrada M, Gutiérrez AR, Rodríguez-García MA, Collazo-Caballero S.¿Radiocirugía o criocirugía en condiloma acuminado de localización anal? Dermatol Peru. 2008;18:98-105. |

| 6. Alfonso-Trujillo I, Rodríguez García MA, Rosa Gutiérrez A, Acosta Medina D, Navarro Maestre M, Collazo Caballero S. ¿Ácido tricloroacético o criocirugía en el tratamiento del condiloma acuminado? Piel. 2009;24(4):176-180. |

| 7. Alfonso-Trujillo I, Alvarez Labrada M, Gutiérrez Rojas AR, Rodríguez García MA, Collazo Caballero S. Condiloma acuminado: eficacia terapéutica comparativa entre la podofilina y la criocirugía. Dermatol Perú. 2008;18(1):27-34. |

| 8. Alonzo Romero Pareyón L, Navarrete Franco G, Hugo Alarcón H, Izabal M. Tratamiento del herpes zóster con ribavirina oral y tópica vs placebo. Efecto sobre la incidencia de neuralgia postherpética. Estudio doble ciego. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2000;9:39-42. |

| 9. Amrouni B, Pereiro M Jr, Iglesias A, Labandeira J, Toribio J. Estudio comparativo en fase iii del clotrimazol y flutrimazol en la vulvovaginitis candidiásica aguda. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1999;90(S1)72-73. |

| 10. Calderón C, Gutiérrez RM. Imiquimod al 5% en el tratamiento del carcinoma basocelular. Evaluación de la eficacia y tolerabilidad. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2002;46:114-120. |

| 11. Carbajosa Martínez J, Arenas R. Onicomicosis. Evaluación de la utilidad del curetaje quirúrgico en el tratamiento combinado (oral y tópico). Dermatología CMQ. 2008;6(3):157-162. |

| 12. Castillo-Oliva A, Alfonso-Trujillo I, Montecer-Ramosa B, Nodarse-Cuníb H, Pérez-Alonso T, Collazo-Caballero S, et al. Uso de crema de interferón alfa leucocitario humano en condilomas acuminados. Piel. 2009; 24(7):350-353. |

| 13. Catacora-Cama J, Cavero-Guardamino J, Manrique-Silva D, Delgado-González V, Aliaga-Ochoa E. Estudio comparativo de la seguridad y eficacia del furoato de mometasona vs dipropionato de betametasona en psoriasis. Folia Dermatol Per. 2001;12:1-6. |

| 14. Chouela E, Fleischmajer R, Pellerano G, Poggio N, Demarchi M, Mozzone R, et al. Tetraciclinas en el tratamiento de la psoriasis. Dermatol Argentina. 2004;4:307-312. |

| 15. Domínguez Soto L, Hojyo MT, Eljure N, Ranone VA, Garibay Valencia M, Fortuño Cordova V. Estudio comparativo entre 5-fluorouracilo a 0,5% en liposomas y 5-fluorouracilo a 5%, crema en tratamiento de queratosis actínica. Dermatología CMQ. 2010;8:173-183. |

| 16. Dominguez-Gomez J, Daniel-Simón R, Abreu-Daniel A. Eficacia del ácido glicirricínico (Herpigen-Glizygen) y un inmunoestimulador (Viusid) en el tratamiento de verrugas genitales. Folia Dermatol Cub. 2008;2(3). |

| 17. Dressendörfer LM, Jervis C, Palacios S. Eficacia terapéutica con el método de Goeckerman en pacientes con psoriasis en placas. Trabajo realizado en el servicio de Dermatología del Hospital Carlos Andrade Marín (Ecuador), agosto-noviembre de 2001. Rev Argent Dermatol. 2006;87:238-246. |

| 18. Fernández G, Enríguez J. Onicocriptosis: estudio comparativo del periodo posoperatorio de una matricectomía parcial lateral con el de una matricectomía parcial lateral con fenolización. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2006;50:87-93. |

| 19. Ferrándiz C, Bielsa I, Ribera M, Fuente MJ, Carrascosa JM. Terapia de refuerzo en pacientes con psoriasis tratada con calcipotriol. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 1998;89:626-630. |

| 20. Fonseca Capdevila E. Eficacia de eberconazol crema al 1% frente a clotrimazol crema al 1% en pacientes con micosis cutáneas. Piel. 2004;19:480-484. |

| 21. Fonseca Capdevila E, López Bran E, Fernández Vozmediano JM, Torre Fraga C de la;, Querol Nasarre I, Moreno Giménez JC. Prevención de secuelas cicatriciales de la extirpación de lesiones cutáneas benignas: estudio multicéntrico, prospectivo, abierto y controlado que compara un gel de silicona y láminas de silicona en 131 pacientes con nevos melanocíticos. Piel. 2007;22(9):421-426. |

| 22. Fonseca E, del Pozo J, Márquez M, Herrero E, Fillat O, Torres J, rt al. Evaluación de la eficacia y seguridad del sertaconazol en crema en aplicación única diaria en el tratamiento de las dermatofitosis. Piel. 1997;12 183-188. |

| 23. Gajardo Julio G, Valenzuela Gabriel R. Eficacia de la tretinoína tópica en fotoenvejecimiento cutáneo: estudio doble ciego randomizado. Rev Chil Dermatol. 2002;18:111-116. |

| 24. Galarza Manyari C. Eficacia y seguridad del tratamiento tópico con capsaicina 0,075 por ciento vs capsaicina 0,050 por ciento en el tratamiento de la neuralgia postherpética. Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo. Marzo 2003-febrero 2004. Dermatol Peru. 2005;15:108-112. |

| 25. Gaxiola-Álvarez E, Jurado Santa-Cruz F, Domínguez-Gómez MA, Peralta-Pedrero ML. Tratamiento de la alopecia areata en placas con capsaicina en ungüento al 0,075%. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2012;21:91-98. |

| 26. Guerra-Tàpia A, Díaz-Castella JM, Balañá-Vilanova M, Borràs-Múrcia C. Estudio para valorar la repercusión de una intervención informativa en la expectativa, el cumplimiento y la satisfacción de los pacientes con onicomicosis tratados con terbinafina. Estudio TERESA. Piel. 2005;20:211-218. |

| 27. Guerrero Robinson A, Medina Raquel K, Kahn Mariana Ch, Guerrero Javiera M. Utilidad y seguridad del 17-alfa-estradiol 0, 025 por ciento versus minoxidil 2 por ciento en el tratamiento de la alopecia androgénica. Rev Chil Dermatol. 2009;25(1):21-25. |

| 28. Herrán P, Ponce R, Tirado A. Eficacia y seguridad del 2-octil cianoacrilato versus sutura simple de heridas quirúrgicas en piel con inflamación crónica. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2011;55:185-187. |

| 29. Hinostroza-da-Conceicao D, Beirana-Palencia A. Tratamiento del molusco contagioso con hidróxido de potasio al 15% en solución acuosa. Dermatol Peru. 2004;14:185-191. |

| 30. Honeyman J. Isotretinoína oral en dosis bajas en el tratamiento del acné moderado. Dermatología Argentina. 1998;4:338-344. |

| 31. Jiménez RN, Aguirre AC, Ponce HS, Velasco AF. Mini injerto autólogo de piel e ingestión de 8-metoxipsoraleno en pacientes con vitiligo vulgar estable. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2002;46:260-267. |

| 32. Lapadula MM, Stengel FM, Maskin M, González P, Kaczvinsky Jr J, Soto R J, Get al. Estudio clínico para evaluar el efecto de dos cremas humectantes con protector solar en la piel de pacientes que utilizan tretinoína 0,025% para el tratamiento del fotodaño. Med Cutan Ibero Lat. 2008;36(5):232-239. |

| 33. Lizárraga García C, Rodríguez Acar M. Impacto de la adherencia en la efectividad de candidina intralesional vs ácido salicílico tópico al 27% en el tratamiento de las verrugas vulgares. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2009;18:5-18. |

| 34. López E, Álvarez M, Agorio C, Avendaño M, Bonasse J, Chavarría A, et al. Tratamiento comparativo entre ivermectina vía oral y permetrina tópica en la escabiosis. Rev Chil Dermatol. 2003;19:27-32. |

| 35. Loyo ME, Zapata G, Santana G. Molusco contagioso: evaluación de diversas modalidades terapéuticas. Dermatología Venezolana. 2003;41(2):25-28. |

| 36. Lugo-Villeda L, Leon-Dorantes G, Blancas González F. Thuja occidentalis homeopática vs- placebo en verrugas vulgares. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2001;45:14-18. |

| 37. Llergo Valdez RJ, Enríquez Merino J. Eficacia y tolerabilidad del polidocanol al 1% en el tratamiento con escleroterapia de várices grado i y ii, empleando compresión en el tercio proximal afectado. Rev Cent Dermatol Pascua. 2008;17:79-83. |

| 38. Maguiña C, Gotuzzo E, Álvarez H. Nuevos esquemas terapéuticos en el loxoscelismo Cutáneo en Lima, Perú. Folia Dermatológica Peruana. 1997;2:1-11. |

| 39. Martín Ezquerra G, Sánchez Regaña M, Umbert Millet P. Tratamiento de psoriasis en placas estable con un preparado que contiene furfuril sorbitol. Med Cután Ibero Lat. 2006;34: 155-158. |

| 40. Martínez-Abundis E, González-Ortiz M, Reynoso-von Drateln C, Pascoe- González S, de la Rosa-Zamboni D. Efecto de una mezcla de champú y anticonceptivos orales sobre el folículo piloso en mujeres sanas. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2004;48:77-81. |

| 41. Martorell-Calatayud A, Requena C, Nagore E, Sanmartín O, Serra-Guillén C, Botella-Estrada R, et al. Ensayo clínico: la infiltración intralesional con metotrexato de forma neoadyuvante en la cirugía del queratoacantoma permite obtener mejores resultados estéticos y funcionales. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011;102:605-615. |

| 42. Méndez-Velarde FA, Salceda-Pérez MA, Borjón-Moya C, Azpeitia- de la O CM, Vázquez-Coronado DP, Ore-Colio L. Efecto de una crema hidratante para prevenir las estrías del embarazo. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2010;54:273-278. |

| 43. Morales-Toquero A, Ocampo-Candiani J, Gómez-Flores M, González -González SE, Eguia-Rodríguez R, Méndez-Olvera NP, et al. Evaluación clínica e histológica de imiquimod a 5% en crema vs 5-fluorouracilo a 5% en ungüento en pacientes con queratosis actínicas en la cara. Dermatología Rev Mex. 2010;54:326-331. |

| 44. Otero V, Bitar R, Rodríguez G. Tratamiento de la miliaria. Estudio comparativo sobre el uso de azitromicina. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cirug Dermatol. 2000;8:249-254. |

| 45. Pinto C, Hasson A, González S, Montoya J, Droppelmann, Inostroza ME, et al. Efecto de la terapia fotodinámica con metil aminolevulinato (MAL) comparada con luz roja en el tratamiento del acné inflamatorio leve a moderado. Rev Chilena Dermatol. 2011;27:177-187. |

| 46. Prada S, Salazar M, Muñoz A, Álvarez L. Tratamiento de úlceras venosas con factores de crecimiento derivados de plaquetas autólogas. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cirug Dermatol. 2000;8:122-128. |

| 47. Queiroz-Telles F, Ribeiro-Santos L, Santamaria J-R, Nishino L, Rocoo N-DO, Milanez V, Bastos C. Tratamiento da onicomicose dermatofitica con itraconazol: comparaçao entre dos esquemas terapéuticos. Med Cutan Ibero Lat. 1997;25:137-142. |

| 48. Ramírez-Bosca A, Zapater P, Betlloch I, Albero F, Martínez A, Díaz-Alperi J, et al. Extracto de polypodium leucotomos en dermatitis atópica. Ensayo multicéntrico aleatorizado, doble ciego y controlado con placebo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:599-607. |

| 49. Regis Roggero A, Pancorbo Mendoza J, Lanchipa Yokota P, Regis Roggero RM, Aguero M. Tratamiento y reinfestación por escabiosis humana: estudio comparativo entre permetrina al 5 por ciento vs benzoato de bencilo al 25 por ciento. Dermatol Peru. 2003;13:30-33. |

| 50. Ríos Yuil JM, Ríos Castro M. Respuesta clínica a las distintas modalidades terapéuticas antifúngicas en pacientes hospitalizados con onicomicosis. Dermatología Venezolana. 2011;49:25-29. |

| 51. Rodas Espinoza AF, Enríquez-M J, Alcalá-P D, Peralta-P ML. Efectividad de la bleomicina intralesional para el tratamiento de pacientes con cicatrices queloides. Estudio comparativo con dexametasona. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2011;55:119-126. |

| 52. Rodríguez C, Sánchez L, Minaya G, Vasquez J, Reymer D, Macher C. Tratamiento de las verrugas vulgares en niños con la hemolinfa del insecto Epicauta sp. Dermatol Peru. 2000;10:94-96. |

| 53. Rodríguez de Rivera-Campillo ME, López-López J, Chimenos-Küstner E. Tratamiento del síndrome de boca ardiente con clonacepam tópico. Piel. 2011;26:263-268. |

| 54. Rodríguez M, Medina-Hernández E. Estudio doble ciego, comparativo, sobre la eficacia y seguridad del crotamitón versus benzoato de bencilo en el tratamiento de la rosácea con demodicidosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2003;47(3):126-130. |

| 55. Rodríguez M. Efectividad de dos pastas de aplicación oral (amlexanox al 5% y clobetasol propionato 0,5%) en el tratamiento de úlceras aftosas recurrentes menores. Estudio clínico controlado, asignado aleatoriamente, enmascarado multicéntrico. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cirug Dermatol. 2004;12:78. |

| 56. Romero G, García M, Vera E, Martínez C, Cortina P, Sánchez P, et al. Resultados preliminares de DERMATEL: estudio aleatorizado prospectivo comparando modalidades de teledermatología síncrona y asíncrona Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2006;97:630-636. |

| 57. Rosón E, García Doval I, Flórez A, Cruce M. Estudio comparativo del tratamiento de la psoriasis en placas con baño de PUVA y UVB de banda estrecha 311nm. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96:371-375. |

| 58. Sáez M, Guimerà F, García M, Dorta S, Escoda M, Sánchez R, et al. Cloruro de aluminio hexahidratado en el tratamiento de las pustulosis palmoplantares Estudio preliminar. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2000;91:416-469. |

| 59. Salomone C, Cárdenas C, Nicklas C, Pérez M-L. La consejería oral y escrita es un instrumento útil para mejorar la adherencia al tratamiento a corto plazo en sujetos con acné vulgar: ensayo clínico randomizado simple ciego. Rev Chil Dermatol. 2009;25(4):339-343. |

| 60. Sánchez M, Iglesias M, Umbert P. Tratamiento de la psoriasis en placas con propiltiouracilo tópico. Actas Dermosifiliogr.2001;92(4):174-176. |

| 61. Sánchez Domínguez MC. Estudio comparativo de la eficacia y seguridad del ácido pirúvico vs crioterapia en el tratamiento de verrugas plantares. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2003;47:219-231. |

| 62. Tirado Sánchez A, Ponce Olivera RM. Eficacia y tolerabilidad del ß-lipohidroxiácido en barra dermolimpiadora en el manejo del acné comedónico leve a moderado. Dermatología CMQ. 2009;7(2):102-104. |

| 63. Tirado-Sánchez A, Ponce-Olivera RM, Montes de Oca-Sánchez G, León-Dorantes G. Calidad de vida y síntomas psicológicos en pacientes con acné severo tratados con isotretinoína. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2006;50:121-126. |

| 64. Valbuena MC, Gamboa LA. Comparación de la eficacia del trimetroprim-sulfametoxazol con el clorhidrato de tetraciclina en el tratamiento de acné nódulo-quístico. Rev Asoc Colomb Dermatol Cirug Dermatol. 1999;7:165-171. |

| 65. Valverde-López J, Lescano-Alva R. Eficacia comparativa de esquemas terapéuticos con cotrimoxazol en pediculosis capitis. Dermatol Peru. 2007;17:21-24. |

| 66. Vázquez González D, Fierro-Arias L, Arellano-Mendoza I, Tirado-Sánchez A, Peniche-Castellanos A. Estudio comparativo entre el uso de apósito hidrocoloide vs uso de tie-over para valorar el porcentaje de integración de los injertos cutáneos de espesor total. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2011;55:175-179. |

| 67. Vences Carranza M, Rodríguez-Acar M. Efecto acaricida del azufre octaédrico, tintura de yodo con ácido salicílico y benzoato de bencilo en el tratamiento de la demodicidosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2004;48:121-126. |

| 68. Vicuña-Ríos D, Tincopa-Montoya L, Valverde-López J, Rojas-Plasencia P, Tincopa-Wong O. Eficacia de las cremas de ciclopirox 1% y ketoconazol 2% en el tratamiento de la dermatitis seborreica facial leve a moderada. Dermatol Perú. 2005;15:25-29. |

| 69. Vidal-Flores A, Enríquez-Merino J. Matricectomía parcial quirúrgica vs matricectomía parcial con electrofulguración en el tratamiento de la onicocriptosis. Dermatol Rev Mex. 2006;50:54-59. |

| 70. Villaseñor Ovies P, Rebollo Domínguez N, Fernández Martínez R, Arenas Guzmán R, Magaña C, Soto Navarro M. Comparación entre bifonazol y ketoconazol en el tratamiento de tinea pedis: resultados de un ensayo clínico. Dermatología CMQ. 2012;10:168-171. |

Please cite this article as: Sanclemente G. Análisis de la calidad de los ensayos clínicos publicados en revistas dermatológicas publicadas en español entre 1997 y 2012. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;107:44–54.