The study of quality of life in patients with skin disorders has become more important in recent decades. In the case of lupus erythematosus, most quality-of-life studies have focused on the systemic form of the disease, with less attention being paid to the cutaneous form. The main objective of this study was to evaluate quality of life in patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) using a dermatology-specific questionnaire: the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Our secondary objective was to investigate associations between DLQI scores and other aspects of the disease.

Material and methodsThirty-six patients with CLE completed the DLQI questionnaire. Other factors assessed were disease severity (measured using the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index), time since diagnosis, body surface area affected, previous and current treatments, and the presence of criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

ResultsAccording to the DLQI, CLE had a moderate, very large, or extremely large effect on quality of life in 50% of the patients analyzed (18/36). No significant associations were found between DLQI scores and disease severity, time since diagnosis, body surface area affected, number, type, or duration of pharmacologic treatments, or the presence or absence of SLE criteria.

ConclusionCLE has a significant and lasting effect on patient quality of life. This effect is probably due to multiple factors, being the most important the chronic nature of the disease, the visibility of the lesions, and the fact that they can cause disfigurement.

La determinación de la calidad de vida (CdV) en las enfermedades dermatológicas ha ganado importancia en las últimas décadas. En el caso del lupus eritematoso, la forma sistémica ha recibido una mayor atención, siendo el lupus eritematoso cutáneo (LEC) evaluado en menor medida. Nuestro objetivo principal consistió en determinar la CdV de los pacientes con LEC utilizando un cuestionario específico para Dermatología, el Índice de calidad de vida en Dermatología (DLQI). Los objetivos secundarios consistieron en valorar la existencia de asociación entre el DLQI y otros aspectos de la enfermedad.

Material y métodosUn total de 36 pacientes con LEC completaron el cuestionario DLQI. Se evaluaron también otros factores: gravedad de la enfermedad (medida con el área e índice de severidad del lupus eritematoso cutáneo [CLASI]), fecha de diagnóstico, área corporal afectada, tratamientos previos y actuales y presencia de criterios de lupus eritematoso sistémico (LES).

ResultadosEn el 50% (18/36) de los pacientes, el LEC tuvo un impacto moderado, grande o extremadamente grande en la CdV. No se encontraron asociaciones entre la puntuación en el DLQI y gravedad de la enfermedad, fecha de diagnóstico, área corporal afectada, número, duración o grupo farmacológico empleado, ni con la presencia o ausencia de criterios de LES.

ConclusiónEl LEC tiene un impacto importante y duradero en la CdV. Entre múltiples factores, la visibilidad, el potencial desfigurante de las lesiones cutáneas, así como la evolución crónica de la enfermedad, son probablemente los principales responsables de dicho impacto.

Evaluation of health-related quality of life (QOL) has become increasingly important in recent years.1–3 In dermatology, various instruments have also been developed to evaluate the impact of skin disease on QOL. Measurement of QOL is useful in everyday clinical practice and research and for administrative purposes, political purposes (patient associations), and economic purposes (pharmaceutical companies, product evaluation).1,4 QOL also plays an important role in adherence, since both QOL and empathy on the part of the clinician contribute to patient satisfaction and, thus, adherence to treatment.5 In the case of lupus erythematosus, most publications focus on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with less attention being paid to cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE). Both types have had a considerable impact on QOL.6

Our primary objective was to evaluate the impact of CLE on QOL. Our secondary objective was to determine the effect on QOL of other factors, such as disease severity, time since diagnosis, body surface area affected, systemic medication, and the presence of SLE criteria.

Material and MethodsWe performed a cross-sectional study between February and June 2012. The study population comprised patients diagnosed with CLE at the Department of Dermatology, Complejo Hospitalario de Pontevedra, Pontevedra, Spain (now known as Xestión Integrada Pontevedra-Salnés). We included patients aged more than 18 years with chronic CLE (CCLE), subacute CLE (SCLE), and acute CLE (ACLE). Classification was based on clinical criteria (morphology, location, progress of the lesions, and presence or absence of scarring). In addition, all the study patients presented histopathologic abnormalities consistent with CLE. Patients with lupus tumidus were excluded because of the clinical characteristics, unpredictable course, and problematic classification of this variant. We also excluded patients with a provisional or uncertain diagnosis and patients with overlap syndrome. Patients were informed about the aims and conduct of the study by telephone. If they verbally agreed to participate, an appointment was made at the dermatology clinic. All the participants signed an informed consent document. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Galicia, Spain approved the study. We recorded the following information: age, sex, date of diagnosis, CLE subtype, presence of SLE criteria, body surface area affected, previous and current treatment, score on the QOL evaluation scale, and disease severity. QOL was evaluated using the validated Spanish-language version of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI),7 a questionnaire comprising 10 questions on cutaneous involvement in terms of symptoms and feelings, activities of daily living, leisure and free time activities, work or studies, personal relationships, and treatment. The maximum score is 30 points. The scoring system was as follows: 0-1, no effect; 2-5, slight effect; 6-10, moderate effect; 11-20, large effect; 21-30, extremely large effect. The tool used to evaluate disease severity was the Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index (CLASI). This scale takes into account 2 different scores, one referring to disease activity and the other to damage/scarring. The maximum score is 70 points. Scoring was as follows: 0-9 points, mild disease; 10-20 points, moderate disease; 21-70 points, severe disease.8,9 Both the DLQI and the CLASI were used with the authors’ permission.

Statistical AnalysisData were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using Stata 10.1.

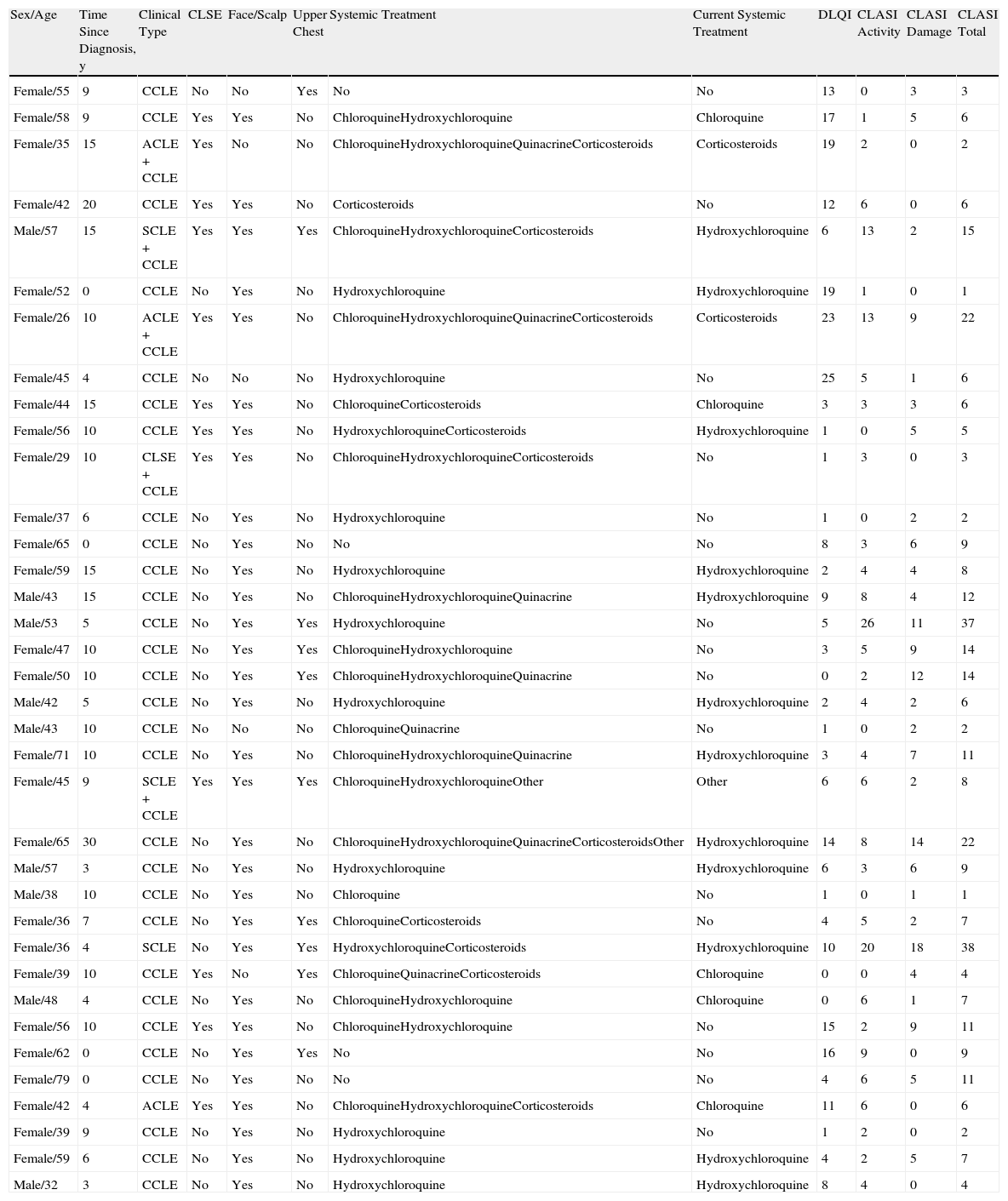

ResultsDemographic DataThe sample comprised 36 patients, of whom 27 were women (75%) and 9 were men (25%). Mean (SD) age was 48.4 (11.9) years, and 50% of patients had been diagnosed with CLE more than 9 years previously. As for subtypes, 94.4% of patients had CCLE (34/36), 11.1% had SCLE (4/36), and 8.3% had ACLE (3/36). The sum of the subtypes was greater than the total, since some patients simultaneously presented manifestations of more than one subtype. The criteria for SLE were met by 32.4% (11/34) of patients with CCLE, 75% (3/4) of patients with SCLE, and 100% (3/3) of patients with ACLE. Patient data are shown in Table 1. The location of the lesions in all patients was recorded as specified in the CLASI; however, for reasons of space, only involvement of the most visible areas is shown in Table 1 (i.e., face, scalp, and upper chest).

Description of Patients With Lupus Erythematosus Included in the Study.

| Sex/Age | Time Since Diagnosis, y | Clinical Type | CLSE | Face/Scalp | Upper Chest | Systemic Treatment | Current Systemic Treatment | DLQI | CLASI Activity | CLASI Damage | CLASI Total |

| Female/55 | 9 | CCLE | No | No | Yes | No | No | 13 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Female/58 | 9 | CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquine | Chloroquine | 17 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| Female/35 | 15 | ACLE+CCLE | Yes | No | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineQuinacrineCorticosteroids | Corticosteroids | 19 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Female/42 | 20 | CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | Corticosteroids | No | 12 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Male/57 | 15 | SCLE+CCLE | Yes | Yes | Yes | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineCorticosteroids | Hydroxychloroquine | 6 | 13 | 2 | 15 |

| Female/52 | 0 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine | 19 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Female/26 | 10 | ACLE+CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineQuinacrineCorticosteroids | Corticosteroids | 23 | 13 | 9 | 22 |

| Female/45 | 4 | CCLE | No | No | No | Hydroxychloroquine | No | 25 | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Female/44 | 15 | CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | ChloroquineCorticosteroids | Chloroquine | 3 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Female/56 | 10 | CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | HydroxychloroquineCorticosteroids | Hydroxychloroquine | 1 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Female/29 | 10 | CLSE+CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineCorticosteroids | No | 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Female/37 | 6 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | No | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Female/65 | 0 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | No | No | 8 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Female/59 | 15 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Male/43 | 15 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineQuinacrine | Hydroxychloroquine | 9 | 8 | 4 | 12 |

| Male/53 | 5 | CCLE | No | Yes | Yes | Hydroxychloroquine | No | 5 | 26 | 11 | 37 |

| Female/47 | 10 | CCLE | No | Yes | Yes | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquine | No | 3 | 5 | 9 | 14 |

| Female/50 | 10 | CCLE | No | Yes | Yes | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineQuinacrine | No | 0 | 2 | 12 | 14 |

| Male/42 | 5 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine | 2 | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Male/43 | 10 | CCLE | No | No | No | ChloroquineQuinacrine | No | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Female/71 | 10 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineQuinacrine | Hydroxychloroquine | 3 | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Female/45 | 9 | SCLE+CCLE | Yes | Yes | Yes | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineOther | Other | 6 | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| Female/65 | 30 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineQuinacrineCorticosteroidsOther | Hydroxychloroquine | 14 | 8 | 14 | 22 |

| Male/57 | 3 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine | 6 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Male/38 | 10 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Chloroquine | No | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Female/36 | 7 | CCLE | No | Yes | Yes | ChloroquineCorticosteroids | No | 4 | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Female/36 | 4 | SCLE | No | Yes | Yes | HydroxychloroquineCorticosteroids | Hydroxychloroquine | 10 | 20 | 18 | 38 |

| Female/39 | 10 | CCLE | Yes | No | Yes | ChloroquineQuinacrineCorticosteroids | Chloroquine | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Male/48 | 4 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquine | Chloroquine | 0 | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Female/56 | 10 | CCLE | Yes | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquine | No | 15 | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Female/62 | 0 | CCLE | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | 16 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| Female/79 | 0 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | No | No | 4 | 6 | 5 | 11 |

| Female/42 | 4 | ACLE | Yes | Yes | No | ChloroquineHydroxychloroquineCorticosteroids | Chloroquine | 11 | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Female/39 | 9 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | No | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Female/59 | 6 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine | 4 | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Male/32 | 3 | CCLE | No | Yes | No | Hydroxychloroquine | Hydroxychloroquine | 8 | 4 | 0 | 4 |

Abbreviations: ACLE, acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; CCLE, chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus; CLASI, Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus Disease Area and Severity Index; CLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; SCLE, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus

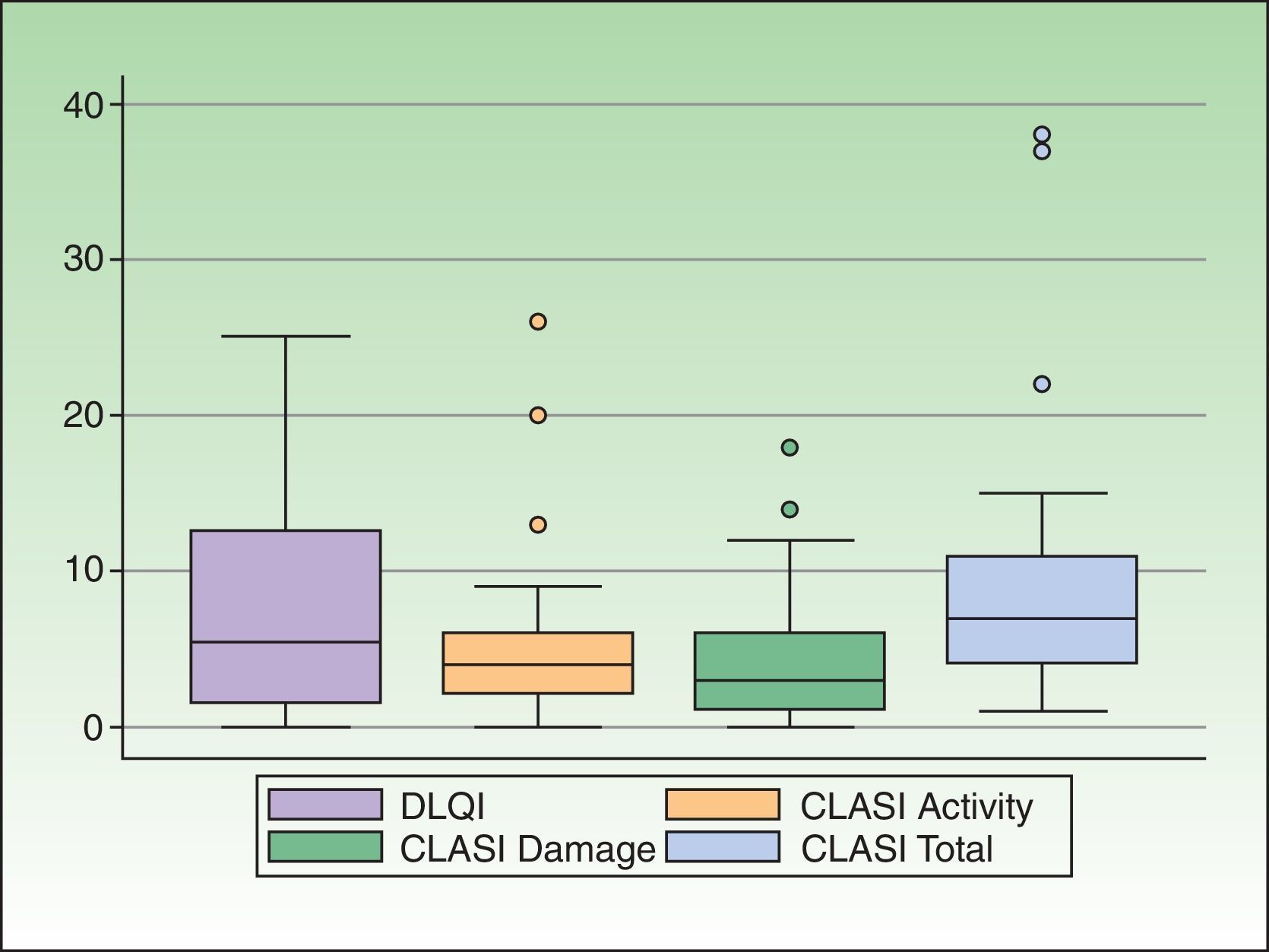

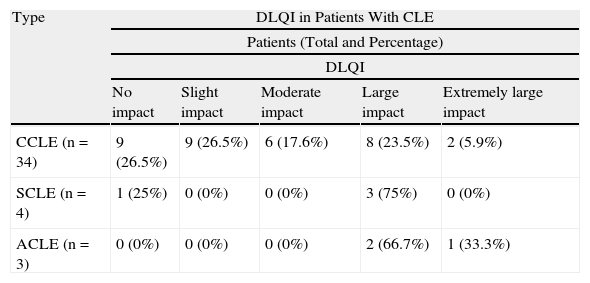

CLE had a slight or no effect on the QOL of 50% of the patients (18/36). In the remaining 50%—an appreciable percentage—the impact on QOL of CLE was moderate (19.4%, 7/36), large (25%, 9/36), or extremely large (5.5%, 2/36). Taking into account only patients with CCLE, 47.1% (16/34) had a moderate to extremely large effect on QOL. The effect was greater in patients with SCLE and ACLE, and 75% (3/4) and 100% (3/3), respectively, presented a moderate to extremely large effect. The DLQI scores are shown in Table 1. The distribution of the DLQI score by disease subtype is shown in Table 2. The distribution of the DLQI scores in the total study population is shown in Figure 1. The mean (SD) DLQI value was 7.6 (SD 6.94) for the whole study population and 7.4 (SD 7.1) for patients with CCLE.

DLQI in Patients With Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Number of Patients in Each Category.

| Type | DLQI in Patients With CLE | ||||

| Patients (Total and Percentage) | |||||

| DLQI | |||||

| No impact | Slight impact | Moderate impact | Large impact | Extremely large impact | |

| CCLE (n=34) | 9 (26.5%) | 9 (26.5%) | 6 (17.6%) | 8 (23.5%) | 2 (5.9%) |

| SCLE (n=4) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (75%) | 0 (0%) |

| ACLE (n=3) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (66.7%) | 1 (33.3%) |

Abbreviations: ACLE, acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus; CCLE, chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus; CLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; SCLE, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

Disease severity was as follows: mild, 69.4% (25/36); moderate, 19.4% (7/36); and severe, 11.1% (4/36). The CLASI scores (activity scale, damage scale, total) are shown in Table 1. The distribution of the CLASI score in the whole study population is shown in Figure 1. The median (IQR) score was 4 (2-6) for CLASI activity, 3 (1-6) for CLASI damage, and 7 (4-11) for CLASI total.

Association Between QOL and Other FactorsGiven the small sample size, the association between DLQI score and other factors was only analyzed in the CCLE group. No significant differences were found between the DLQI score and involvement of the face or scalp (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P=.57 and P=.97), DLQI and number of previous or current systemic treatments (nonparametric trend test: P=.64), DLQI and the presence of SLE criteria (Wilcoxon rank sum test: P=.32), or DLQI and time since diagnosis (linear regression: P=.97). The correlation between the DLQI and the CLASI scores was very low (Pearson r=0.18 for the CLASI activity score, 0.02 for the CLASI damage score, and 0.13 for the CLASI total score). When disease severity was taken into account, the mean DLQI scores were 7.1 (moderate effect on QOL) in patients with mild disease, 5.7 (slight effect on QOL) in those with moderate disease, and 14 (large effect on QOL) in those with severe disease.

DiscussionA wide variety of questionnaires can be used to measure QOL. Some are valid for several diseases, whereas others are specific to a particular system or disease.1 The Short Form 36 health questionnaire (SF-36), the Sickness Impact Profile, the Nottingham Health Profile, and the General Health Questionnaire are examples of generic questionnaires,3 which enable comparisons to be made between different diseases affecting different systems.1 Dermatology-specific questionnaires include the DLQI, the Skindex, the Dermatology Quality of Life Scales, the Dermatology-Specific Quality of Life instrument, and the Qualita di Vita Italiana in Dermatologia (Italian Quality of Life in Dermatology) questionnaire.4

Despite the availability of more up-to-date, change-sensitive questionnaires such as the Skindex-29, which are useful, for example in clinical trials,4,10–12 the DLQI was the first to be developed and the most widely used in dermatology, as it is specifically designed for skin diseases and frequently used to evaluate the impact of a disease before systemic treatment is started. It is easy to complete, efficient, and reproducible, and a Spanish-language version has been validated.7,13 Consequently, the DLQI was the questionnaire we selected for our study.

We selected the CLASI to measure the severity of CLE, since it is currently the only formally validated questionnaire for this purpose.14 Despite its limitations (noninclusion of lesional induration, subjectivity in evaluation of alopecia, evaluation of the most severe lesion instead of providing a global evaluation of all the lesions, and inclusion of all forms of CLE),15 the CLASI activity score and the CLASI damage score show, respectively, an excellent correlation and a moderate correlation with general health status, as evaluated by the physician and the patient.8 The CLASI score also correlated with the improvement in general health status and has proven useful for measuring response to therapy.8,16 Independent evaluation of activity and damage is very useful, since the CLE damage score usually remains stable and generally does not improve with drugs.8

Owing to its chronic course and potential for causing disfiguring lesions, CLE (with CCLE as the most prevalent variant) can have a considerable effect on QOL, and involvement of photoexposed areas can diminish the patient's self-confidence and self-esteem.2 The presence of scarring and hypopigmentation, which are invariably persistent, means that improvement of the disease is not always correlated with an improvement in QOL.6 However, in our study, QOL in the CCLE group was no worse than in the other groups, although the low number of patients with SCLE and ACLE would only enable very large differences to be detected.

Most studies on QOL in lupus erythematosus focus on SLE. In patients with this disorder, QOL associated with body image has also been evaluated using the Body Image Quality of Life Inventory, whose score was significantly lower (worse QOL) in patients with SLE than in controls.17

Klein et al.9 evaluated the QOL (Skindex-29 and SF-36) and disease severity (CLASI) of 157 patients with CLE at a reference center in Pennsylvania in the United States. Since the SF-36 is not specific for dermatologic complaints (see above), it enables the results for patients with lupus erythematosus and those with other diseases to be compared. Patients with CLE were observed to have worse QOL than those with acne, nonmelanoma skin cancer, and alopecia. With respect to the psychological subdomain of QOL, patients with CLE had similar or worse scores than patients with hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, myocardial infarction, and congestive heart failure. The factors related to worse QOL were female sex, generalized or severe disease, distribution of lesions (scarring alopecia), and younger age. Vasquez et al.18 performed a similar study with 91 patients from Texas in the United States in order to compare their results with those of the population from Pennsylvania in the study by Klein et al. and investigate differences in the QOL of patients from different geographic areas. They observed that the Skindex and SF-36 scores were very similar in both study populations, although significant differences were observed for the subdomains of physical functioning, lupus-specific subdomain, and general health status, all of which scored worse in the patients from Texas. The factors associated with worse QOL in this group were female sex, lower income, high educational level, presence of SLE, and greater disease activity.

The DLQI has also been used to evaluate QOL in patients with lupus erythematosus. Ferraz et al.19 evaluated QOL in 71 patients with lupus erythematosus and skin lesions (45 patients with CCLE and 26 patients with SLE) and found the mean DLQI score to be 6.5. Martins et al.20 performed a comparative study of QOL in patients with CCLE (only discoid type) and patients with SLE, including 26 patients in the first group and 38 in the second. Lower values were found in the DLQI in patients with discoid CCLE (mean value of 6.5 [moderate impact]) than in patients with SLE (mean value 12.4 [large impact]). Our study showed similar results with respect to the mean DLQI values, which fell within the range for moderate impact on QOL.

We found no association between QOL and disease severity, time since diagnosis, involvement of more visible areas, number or family of previous or current systemic drugs, or presence of SLE criteria. The absence of significant differences could be explained by the small sample size. QOL can also be influenced by changes in the location of the lesions (visible or nonvisible areas), in such a way that disease activity can increase owing to the appearance of lesions in covered areas, thus compromising QOL less than if the lesions were on the face or scalp. The need for stringent photoprotective measures and the adverse effects of systemic treatment can affect QOL despite the absence of skin lesions. Furthermore, scarring skin lesions do not improve QOL, even if disease activity has ceased. Consequently, the correlation between DLQI and CLASI is weak.

ConclusionQOL is considerably compromised in patients with CLE, and outcome is determined by several factors. Given the visibility of the lesions, QOL is affected even if disease activity is low. The chronic course of CLE, the disfiguring scars it produces, and the need for stringent photoprotective measures are responsible for the lasting impact on QOL. Therefore, this field should not be overlooked in the global evaluation of patients with CLE. It seems reasonable to pay greater attention to the QOL of patients with CLE. In addition to drugs and sunscreen, these patients should be offered cosmetic treatment to improve the sequelae of the disease.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they followed their hospital's regulations regarding the publication of patient information and that written informed consent for voluntary participation was obtained for all patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Batalla A, García-Doval I, Peón G, de la Torre C. Estudio de calidad de vida en pacientes con lupus eritematoso cutáneo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2013;104:800–806.