Tropical skin diseases are conditions acquired in tropical regions and countries. They affect more than 17000 travelers per year.1 We report the case of a patient with a community-acquired tropical skin disease and comment on diagnosis and treatment.

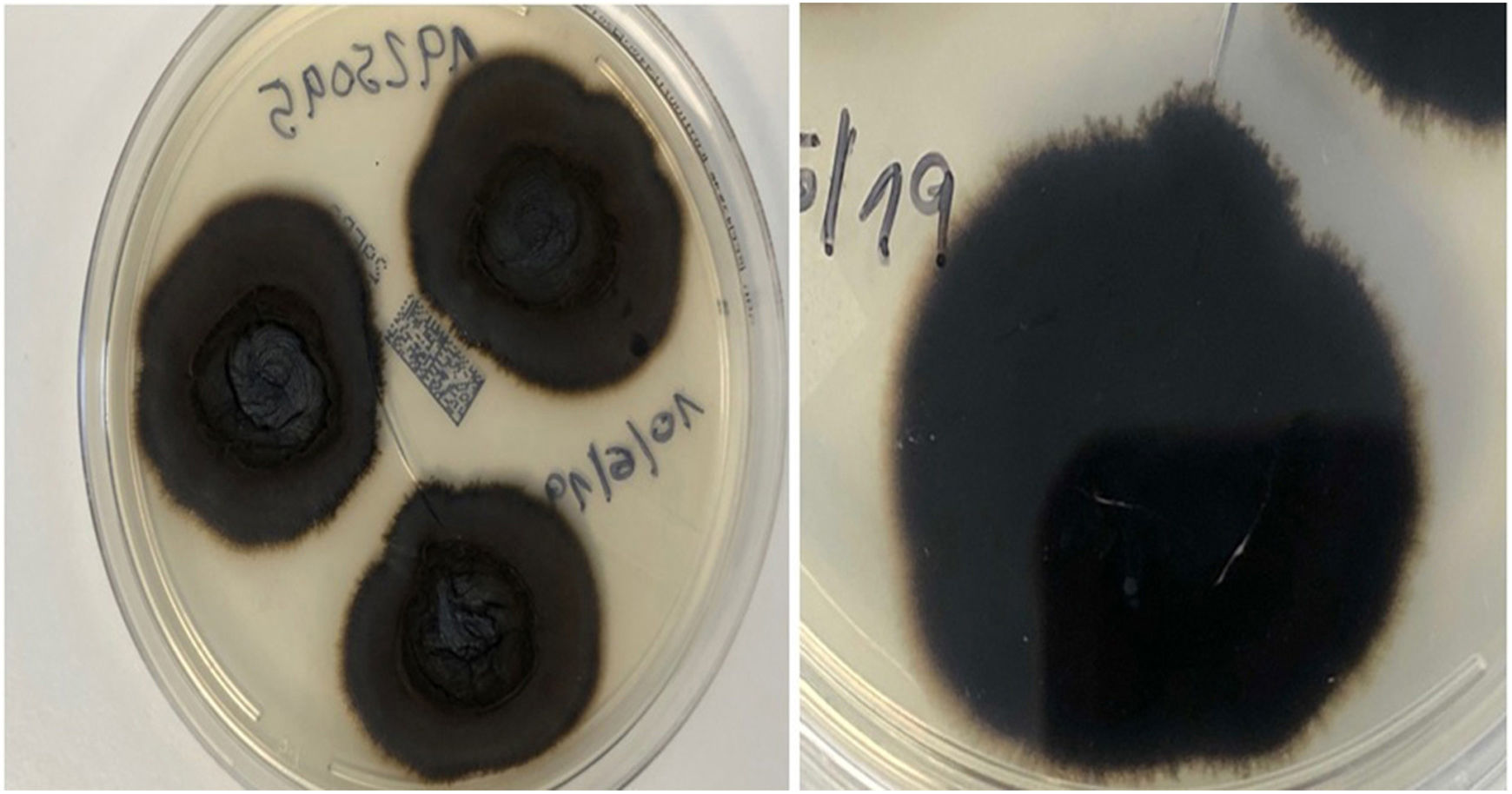

An 82-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, chronic venous insufficiency, and hereditary hemochromatosis attended the clinic with an excrescent suppurative lesion on the dorsum of the left foot. The lesion had first appeared 3 months previously and had been treated unsuccessfully with antiseptics and topical corticosteroids. The patient reported not having traveled outside the autonomous community of Murcia. He kept a kitchen garden and did not recall accidental injury. The physical examination revealed a soft violaceous multilobulated nodular plaque measuring 3cm×4cm (Fig. 1). Examination of a punch biopsy specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intense granulomatous inflammation, foci of abscessification, multinucleate giant cells, and Melar bodies (muriform cells) (Fig. 2). The biopsy specimen was cultured at our hospital in blood-agar and Sabouraud agar media at 30°C. At 21 days, we observed the growth of black colonies (Fig. 3), which, on examination with an optical microscope, were identified as belonging to the genus Exophiala. The strain was sent to the National Microbiology Center, where it was further identified using ribosomal DNA sequencing as Exophiala bergeri. The patient was treated with itraconazole 200mg/d. Nevertheless, he died of septic shock secondary to septic arthritis of the knee after 8 months of follow-up. His skin lesion had improved slightly.

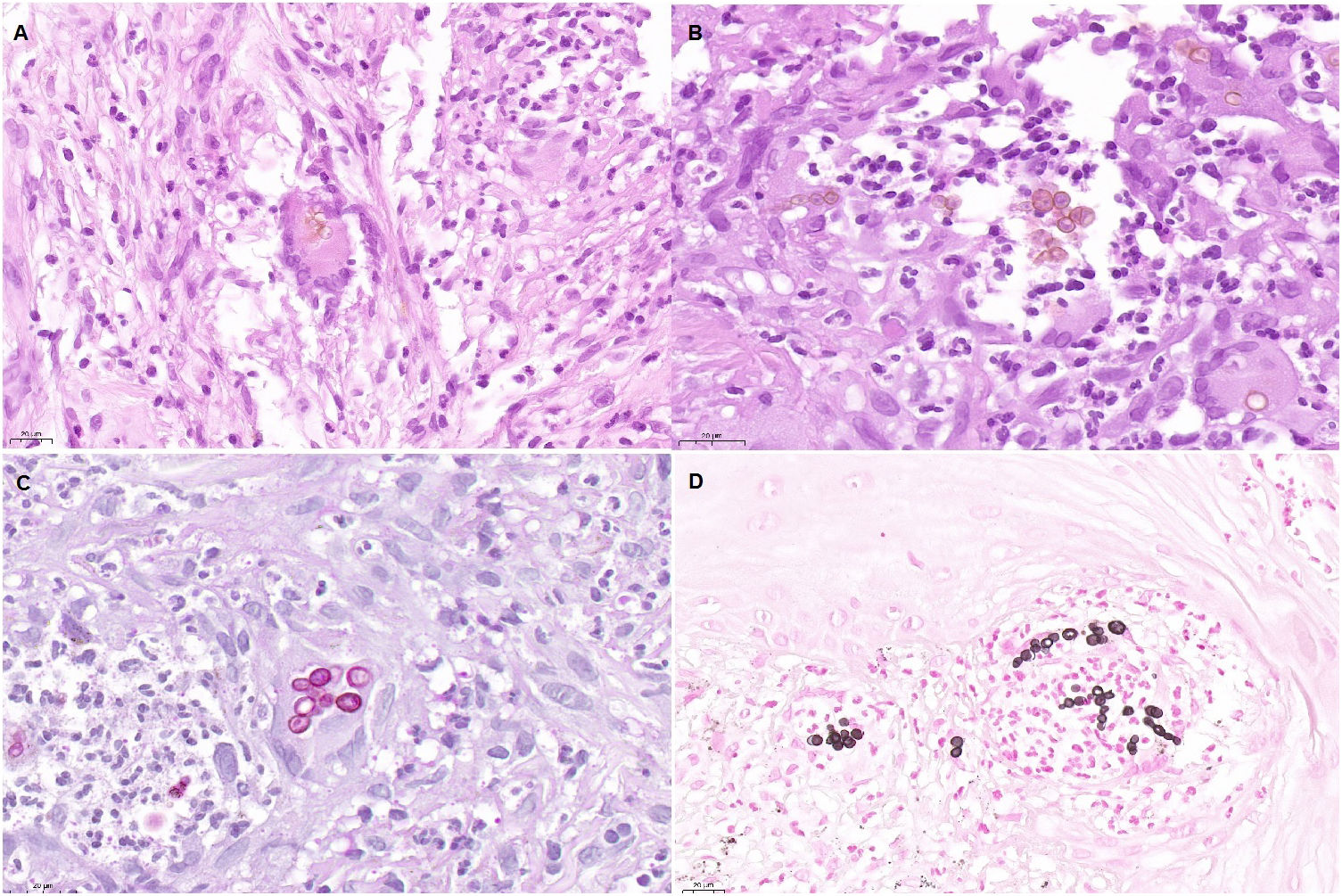

Histopathology findings. A, Histologic section (hematoxylin–eosin, ×40). Note the multinucleate giant cell in the center of the image, with Medlar bodies (muriform cells) in the interior. B, Histologic section (hematoxylin–eosin, ×63). The Medlar bodies are clearly visible in the center of the image. C, Histologic section (periodic acid–Schiff, ×40) showing detail of the Medlar bodies. D, Histologic section (methenamine silver, ×40) showing detail of the Medlar bodies.

Chromoblastomycosis is a verrucous skin disease caused by chronic infection of the subcutaneous cellular tissue by dematiaceous fungi. The most common species are Fonsecaea pedrosoi, Fonsecaea compacta, Fonsecaea monophora, Phialophora verrucosa, Cladophialophora carrionii, and Rhinocladiella aquaspersa. Exophiala bergeri, on the other hand, is a much less common species.2,3

The disease occurs mostly in tropical and subtropical regions (Caribbean, Africa, Australia, and Japan). The reservoir can be the ground, plants, and decomposing wood. Therefore, cases are typically reported among rural workers such as farmers, cattle farmers, and miners and mainly involve men. The portal of entry is usually a lesion on the limbs. Chromoblastomycosis is considered an occupational disease throughout the world. While there have been reports of cases in immunodepressed patients (especially those with cancer and solid organ recipients), it mainly affects immunocompetent persons.2,3

The disease manifests clinically as a papule or nodule, typically on the leg, that progresses to form a verrucous or granulomatous plaque. Diagnosis requires a full clinical history and culture of a biopsy specimen. Histopathology findings are very characteristic, i.e., Medlar bodies (which are pathognomonic), and enable the disease to be differentiated from phaeohyphomycosis, a fungal disease caused by dematiaceous fungi that mostly affects immunodepressed patients. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the diagnosis is confirmed based on microbiological findings. The differential diagnosis includes other diseases, such as cutaneous tuberculosis, tertiary syphilis, blastomycosis, leishmaniasis, and phaeohyphomycosis.2,3

Therapeutic options are limited.2,3 In the case of localized disease, we can turn to surgical resection with suitable margins. In disseminated disease, the approach of choice comprises systemic antifungal agents, which may be combined with other treatments. The most widely used are itraconazole (200–400mg/d) and terbinafine (250–500mg/d). These should be administered over long periods (8–36 months), since the response is slow. The infection is cured in up to 85%–90% of cases. Itraconazole in pulses (400mg daily for 1 week per month over 6–12 months) was recently shown to be successful. Posaconazole and voriconazole have proven effective in patients who did not respond to itraconazole and terbinafine. Amphotericin B, 5-fluorocytosine, ketoconazole, and thiabendazole are less commonly used owing to their poor risk-benefit ratio. As for physical approaches, cryotherapy and heat therapy have proven effective alone and when combined with systemic antifungal agents. A favorable response to photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid has also been reported, especially when combined with systemic antifungal agents.4 Other treatments include CO2 laser therapy and topical imiquimod.5,6

We were only able to find 7 reported autochthonous cases of chromoblastomycosis in Spain.7–10 Only 1 case involved an immunodepressed patient.7

Here, we report the eighth case of chromoblastomycosis acquired in Spain. It is important to bear this diagnosis in mind when addressing a suppurative nodule or papule that progresses to a verrucous or granulomatous plaque on the lower limbs, even in cases with no history of travel to a tropical region. The characteristics of autochthonous patients do not differ from the prototypical model. The relationship with the rural environment and associated professions should be stressed.