Reticular patterns are observed in a great variety of skin diseases. While these morphologic patterns are often highly distinctive, they are seldom discussed or studied in clinical contexts or recognized as a diagnostic category in their own right. Diseases presenting with reticulate skin lesions have multiple etiologies (tumors, infections, vascular disorders, inflammatory conditions, and metabolic or genetic alterations) and can range from relatively benign conditions to life-threatening ones. We review a selection of these diseases and propose a clinical diagnostic algorithm based on predominant coloring and clinical features to aid in their initial assessment.

Las enfermedades dermatológicas que cursan con un patrón reticular son múltiples y variadas. Aunque dicho patrón particular de presentación morfológica muchas veces es muy distintivo, usualmente es poco discutido y estudiado en el contexto clínico. A menudo estos patrones no se abordan como una categoría diagnóstica propia. Asimismo, las etiologías de este grupo de enfermedades son diversas, desde causas vasculares, infecciosas, tumorales, inflamatorias, metabólicas o genéticas. Además, pueden variar desde condiciones relativamente benignas hasta enfermedades graves que amenazan la vida. Este artículo tiene como objetivo discutir la enfermedad de la piel que se manifiesta con lesiones reticulares y se propone un algoritmo de diagnóstico clínico, basado en el color predominante de las lesiones y en los principales hallazgos clínicos, para un abordaje práctico inicial.

The term “reticulated” is often used to clinically describe skin lesions configurated in a lattice-like pattern.1

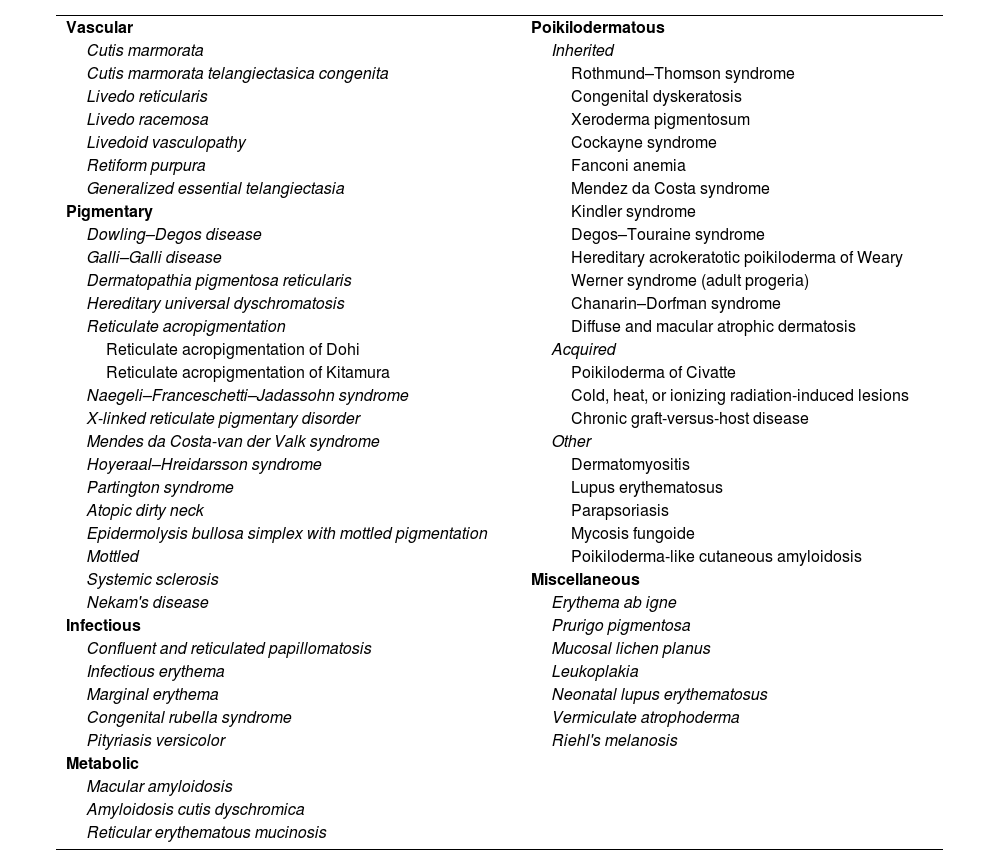

The etiology is varied including vascular, infectious, neoplastic, metabolic, genetic, inflammatory, or idiopathic conditions, exclusively limited to the skin or part of a systemic disease, each with a different prognosis2 (Table 1). Details from the patient's health history, such as location and distribution, along with other signs like the presence of poikiloderma or color, can help guide the diagnosis.3,4

Classification and most important diseases with reticular patterns.

| Vascular | Poikilodermatous |

| Cutis marmorata | Inherited |

| Cutis marmorata telangiectasica congenita | Rothmund–Thomson syndrome |

| Livedo reticularis | Congenital dyskeratosis |

| Livedo racemosa | Xeroderma pigmentosum |

| Livedoid vasculopathy | Cockayne syndrome |

| Retiform purpura | Fanconi anemia |

| Generalized essential telangiectasia | Mendez da Costa syndrome |

| Pigmentary | Kindler syndrome |

| Dowling–Degos disease | Degos–Touraine syndrome |

| Galli–Galli disease | Hereditary acrokeratotic poikiloderma of Weary |

| Dermatopathia pigmentosa reticularis | Werner syndrome (adult progeria) |

| Hereditary universal dyschromatosis | Chanarin–Dorfman syndrome |

| Reticulate acropigmentation | Diffuse and macular atrophic dermatosis |

| Reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi | Acquired |

| Reticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura | Poikiloderma of Civatte |

| Naegeli–Franceschetti–Jadassohn syndrome | Cold, heat, or ionizing radiation-induced lesions |

| X-linked reticulate pigmentary disorder | Chronic graft-versus-host disease |

| Mendes da Costa-van der Valk syndrome | Other |

| Hoyeraal–Hreidarsson syndrome | Dermatomyositis |

| Partington syndrome | Lupus erythematosus |

| Atopic dirty neck | Parapsoriasis |

| Epidermolysis bullosa simplex with mottled pigmentation | Mycosis fungoide |

| Mottled | Poikiloderma-like cutaneous amyloidosis |

| Systemic sclerosis | Miscellaneous |

| Nekam's disease | Erythema ab igne |

| Infectious | Prurigo pigmentosa |

| Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis | Mucosal lichen planus |

| Infectious erythema | Leukoplakia |

| Marginal erythema | Neonatal lupus erythematosus |

| Congenital rubella syndrome | Vermiculate atrophoderma |

| Pityriasis versicolor | Riehl's melanosis |

| Metabolic | |

| Macular amyloidosis | |

| Amyloidosis cutis dyschromica | |

| Reticular erythematous mucinosis |

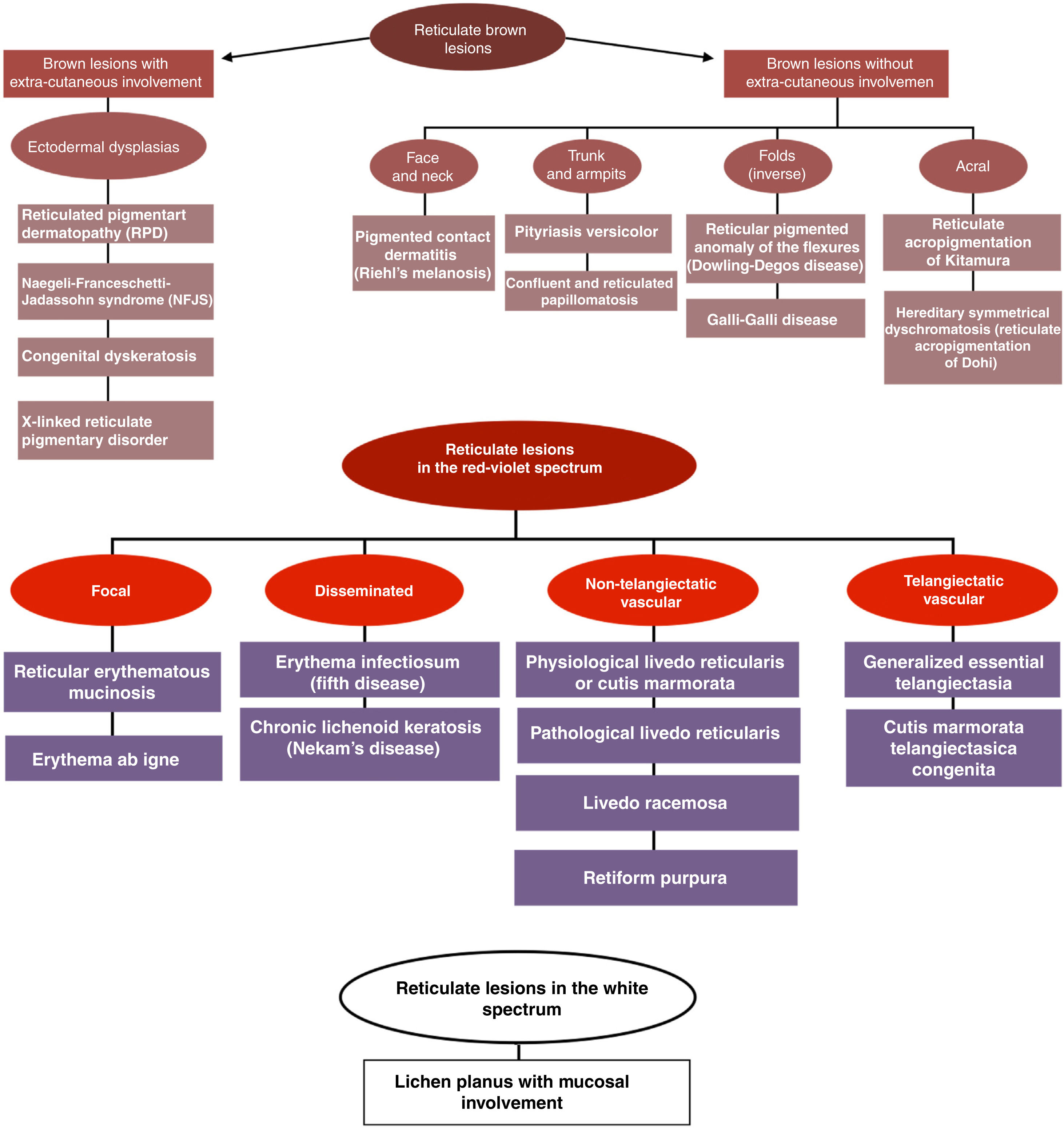

The goal of this article is to propose a clinical diagnostic algorithm for the management of patients with reticular lesions based on the predominant color of these (brown, red-purple, and white) and the main semiotic findings for an early practical approach (Fig. 1).

Additionally, some of the diseases that present with reticular skin lesions will also be briefly described and categorized based on this algorithm. We should mention that the list of diseases is extensive, which is why only the most important ones depending on their frequency of occurrence and clinical relevance will be described.

Reticulate brown lesionsWith extracutaneous componentsReticulated pigmentary dermatosis (RPD): it is characterized by a triad of persistent, diffuse, reticulated hyperpigmentation, non-cicatricial diffuse alopecia, and nail dystrophy. It often presents with punctate palmoplantar keratoderma and hypoplastic dermatoglyphics.5

Naegeli–Franceschetti–Jadassohn syndrome (NFJS): persistent, reticulate, perioral, periocular, and cervical hyperpigmentation after 2 years. Nonetheless, the NFJS is gone in adolescence. It is associated with hypohydrosis, dental involvement, punctate keratoderma, and nail dystrophy.6

Congenital dyskeratosis: a triad of reticulate hyperpigmentation on neck, face, and trunk, along with leukoplakia and nail dystrophy.7 It is often associated with the development of malignancies such as Hodgkin's disease, oropharyngeal, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, and squamous cell carcinomas.8

X-linked reticulate pigmentary disorder: in women, reticulate hyperpigmentation along Blaschko lines that often disappears in adulthood. In men, generalized reticulate hyperpigmentation that often appears between 4 and 5 years old with extracutaneous involvement.9

Without extracutaneous componentsFace and neckPigmented contact dermatitis (Riehl's melanosis): non-spongiotic contact dermatitis associated with daily exposure to low levels of allergens. Its most common presentation is brown-grayish macules of reticular configuration on the face and neck, but is not associated with vesicles, erythema, or itching.10

Trunk and armpitsPityriasis versicolor: superficial mycosis caused by Malassezia spp. characterized by hyperchromic, or hypochromic patches covered with fine scaling, predominantly on the trunk, neck, and upper limbs. It can look like localized, disseminated, or erythrodermic dermatosis and have various morphologies, including punctate, nummular, reticular, follicular, or pseudopapular, hyperchromic, hypochromic, and atrophic.11

Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis: disorder typical of adolescence characterized by the development of hyperpigmented papules with minimal scaling that become confluent in their center, with gradual peripheral spread and a reticular pattern. It often affects the intermammary region, neck, and back.2

Fold areasDowling–Degos disease: autosomal dominant disorder showing after puberty and characterized by symmetrical reticulate hyperpigmentation of neck, armpits, groins, and other flexural areas. It is associated with comedone-like lesions and perioral ice-pick scars.2

Galli–Galli disease: acantholytic variant of Dowling–Degos disease characterized by focal suprabasal acantholysis on the histopathological examination.12

Acral distributionReticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura: Autosomal dominant disease.

The onset of reticulate acropigmentation of Kitamura often occurs during the first and second decades of life. It presents with well-demarcated black/brownish macules, slightly depressed on the dorsal region of hands and feet. The presence of small palmar pits is a diagnostic feature.8,13

Reticulate acropigmentation of Dohi: autosomal dominant disorder whose age of onset starts between the first and second decades of life with hypo- and hyperpigmented macules on the dorsal and ventral surfaces of hands and feet that can spread to the proximal regions of the limbs.8

Reticulate lesions in the red-violet spectrumFocalReticular erythematous mucinosis: dermatosis associated with the gradual deposition of mucin in the dermis. It presents with erythematous, infiltrated, telangiectatic, and reticular papules in the midline of the chest, with or without itching. Reticular erythematous mucinosis predominantly affects young and middle-aged women. Heat, sweating, and sunlight exacerbate the symptoms.14

Erythema Ab Igne (EAI): chronic pigmentary disorder resulting from prolonged exposure to an infrared heat source. EAI shows areas of reticular erythema associated with hyperpigmentation, epidermal atrophy, and telangiectasias, often on the extremities. There may be an increased risk of malignant cutaneous transformation, including squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which makes follow-up an important part of the management of this disease.15

DisseminatedErythema infectiosum: reticular pattern of erythematous eruption on the trunk and limbs triggered by parvovirus B19.4 This pattern typically begins 1–4 days after the appearance of the classic “slapped cheek” rash. It disappears within 2–3 weeks but may reappear after exposure to UV rays and hot baths.2

Nekam's disease: chronic and progressive condition of unknown etiology, often considered a variant of lichen planus. It is characterized by an erythematous face with symmetrically distributed lichenoid keratotic papules of erythematous-violaceous to brown color. These papules cluster in linear or reticular patterns and predominantly affect the lower limbs.16

Non-telangiectatic vascularPhysiological livedo reticularis (LR) or cutis marmorata: physiological response to cold exposure in newborns that disappears upon rewarming. It is characterized by a reticulate bluish vascular pattern involving the limbs and trunk symmetrically. It often resolves by the time the newborn is 6 months old.6

Pathological livedo reticularis: unlike its physiological counterpart, it does not resolve after warming the affected limb, may spread beyond the lower limb, and is often associated with severe systemic involvement of micro- and macro-circulation.17

Livedo racemosa: reticular pattern is often complete in LR, whereas livedo racemosa shows incomplete branching patterns.2 It exhibits a persistent, irreversible, and incomplete reticular network indicative of areas where blood flow is interrupted. When palpable, it is associated with vasculitis following the inflammation of blood vessel walls. If not palpable, it is suggestive of thrombotic disease.18

Retiform purpura: an advanced stage of livedo racemose, often associated with necrosis and ulceration indicative of severe systemic disease.18

Telangiectatic vascularGeneralized essential telangiectasia: benign, asymptomatic, exclusively cutaneous condition characterized by localized or diffuse centripetal telangiectasias in a reticular configuration. The age of onset is often between the 3rd and 4th decades of life.19

Cutis marmorata telangiectasica congenita (CMTC): it is characterized by a reticular vascular mottling resembling physiological cutis marmorata. It stands out from the latter due to its persistent nature (even after rewarming), deep purple color, and association with skin atrophy or ulceration. Distribution can be localized, segmental, or generalized. More than half of the cases reported are associated with other abnormalities.2

Reticulate lesions in the white spectrumLichen planus with mucosal involvement: idiopathic lichenoid inflammatory dermatosis that can damage the hair, nails, and mucous membranes. The presence of whitish, asymptomatic, bilateral striae predominantly affecting the jugal mucosa is a common finding. It is associated with HCV, Helicobacter pylori, vaccination (HBV), and drugs. It spontaneously subsides in up to two-thirds of the patients within the first year after symptom onset.20

DiscussionSkin conditions of reticular pattern include a significant number of diseases and disorders. Their extensive etiology and varied clinical presentation make this pattern of lesions significantly challenging regarding diagnosis. In the medical literature currently available, reticular lesions are often described as a pattern of clinical presentation and grouped within other more common dermatological diseases or as differential diagnosis. They are often not addressed as an integrated category, or as a distinct diagnostic entity, which is why integrating most disorders in a practical way due to this clinical finding is clinically challenging. The proposed algorithm uses the color of the lesion, the topography, and other relevant findings to guide the initial approach. We believe it is a useful tool for dermatologists as it provides an easy-to-use and learn simple method for early assessment purposes. However, it does not make up a comprehensive list of all the diseases that may present with a reticular pattern, or include atypical presentations of the aforementioned conditions. The addition of these diseases is based on the frequency of presentation, local epidemiology, and the most common clinical presentation, which eventually allows color categorization. They are also categorized to facilitate the rapid distinction between systemic diseases with cutaneous components and reticulate disease only limited to the skin given the clinical relevance of this distinction.

We should mention that hereditary reticulate pigmentary disorders of the skin can have various phenotypic expressions, which means that sometimes they may not fit into the proposed algorithm. We believe that its main limitation is the patient's skin phototype. The basic clinical presentation of the aforementioned diseases is often reported in populations with lower skin phototypes, which makes extrapolation difficult to populations with higher phototypes.

Finally, we should mention that diseases that show reticulate skin lesions are numerous, and their diagnosis is often difficult to achieve. An algorithmic approach based on color provides a systematic and simplified diagnostic approach easy to apply and helps guide the diagnosis.

Conflicts of interestNone declared.