Pruritus is the main symptom of many dermatologic and systemic diseases. Atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, contact dermatitis, urticaria, lichen simplex chronicus, mycosis fungoides, scars, autoimmune diseases, kidney or liver diseases among others are all associated with itch that may require different approaches to management. Although antihistamines seem to be the first line of therapy, in reality their role is limited to urticaria and drug-induced reactions. In fact, the pathophysiologic mechanisms of each of the conditions covered in this review will differ. Recent years have seen the emergence of new drugs whose efficacy and safety profiles are very attractive for the management of pruritus in clinical practice. Clearly, we are at a critical moment in dermatology, in which we have the chance to be more ambitious in our goals when treating patients with pruritus.

El prurito es el síntoma principal en múltiples enfermedades dermatológicas y sistémicas. La dermatitis atópica, la psoriasis, la dermatitis de contacto, la urticaria, el liquen simple crónico, la micosis fungoides, las cicatrices, las enfermedades autoinmunes, la enfermedad renal o hepática crónica, entre otras, asocian prurito que puede requerir un manejo terapéutico distinto. Aunque los antihistamínicos parecen ser la primera línea de tratamiento, en realidad su papel queda limitado a la urticaria y reacciones por fármacos, ya que los mecanismos fisiopatológicos de cada una de las entidades tratadas a lo largo de este manuscrito serán distintas. En estos últimos años han aparecido nuevas moléculas para el tratamiento del prurito, con perfiles de eficacia y seguridad muy atractivos para su uso en práctica clínica. Sin duda, es un momento crucial para el desarrollo de la dermatología en el campo del prurito, y una oportunidad para ser más exigentes con los objetivos a alcanzar en estos pacientes.

Biologics that target cytokines of the Th2 pathway such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, opioid agonists/antagonists, NK-1 receptor antagonists, GABAergic receptors such as pregabalin and gabapentin, JAK1 inhibitors such as upadacitinib, abrocitinib, and baricitinib, anti-IL-17 antibodies such as ixekizumab, phototherapy, and classic immunosuppressants such as cyclosporin, are among the therapeutic options currently available. This article will detail the recommended treatments according to the underlying disease.

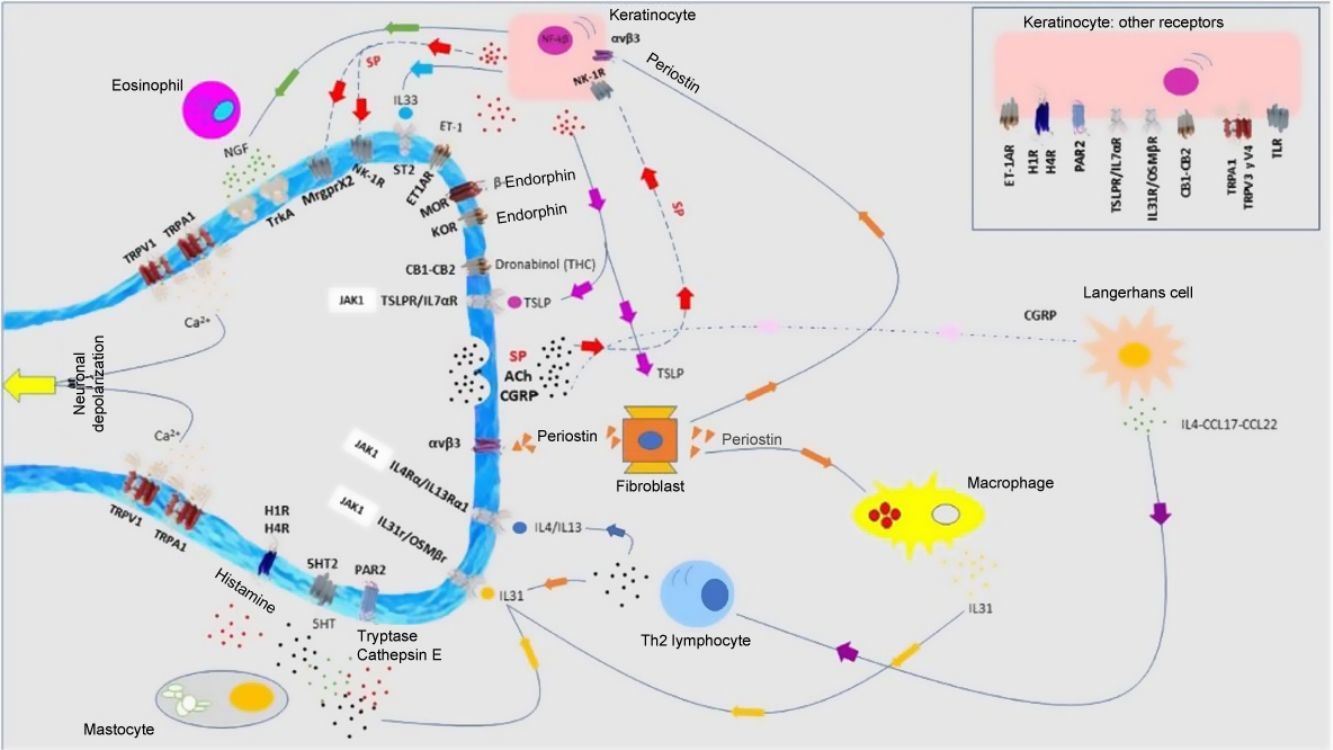

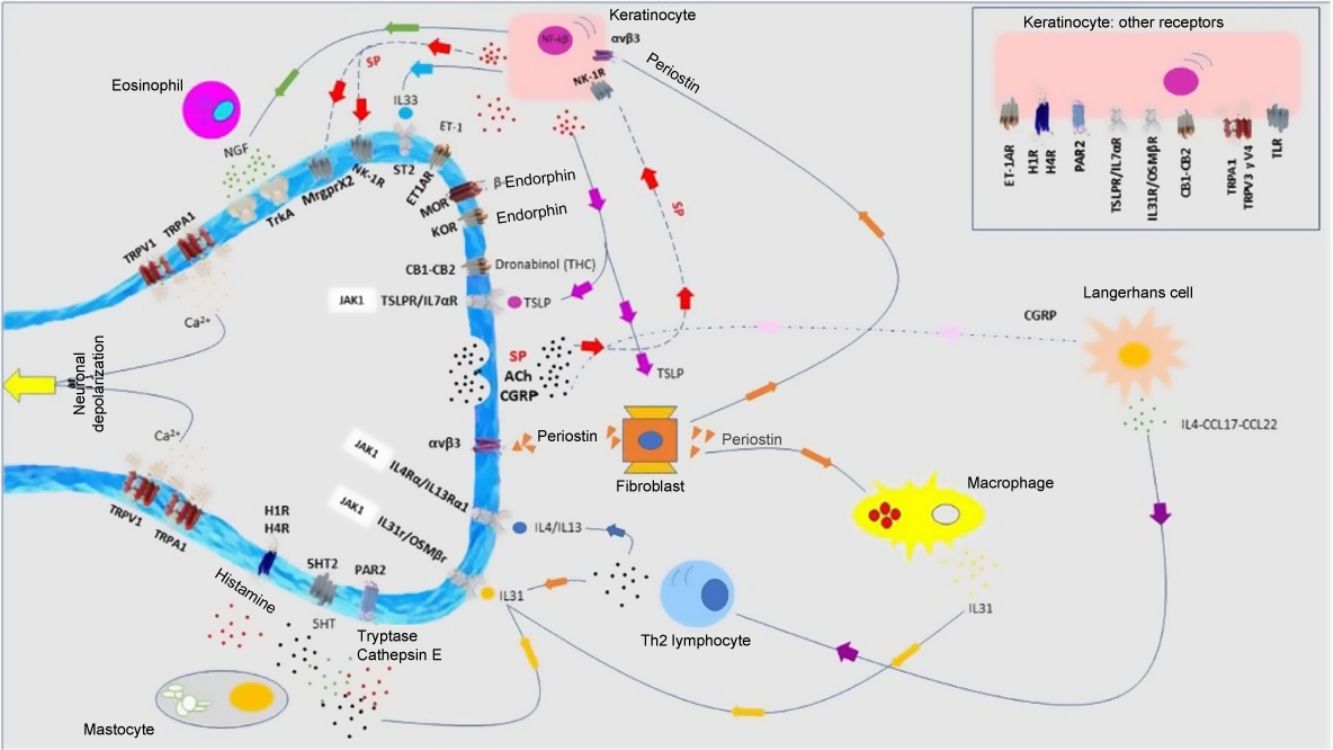

Atopic DermatitisPruritus is one of the diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis (AD). Between 87% and 100% of patients suffer from it.1 It is mainly nonhistaminergic. Cytokines such as IL-4, IL-13, IL-31, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) are important pruritogenic mediators in AD.2 Intracellular signaling is mainly via JAK1,3 although the cannabinoid receptors CB1 and CB2, or opioid receptors KOR have also been identified. NK-1 antagonists improve pruritus without improving eczema. There is overexpression of PAR24 and TRPV3.5 TRPV3 increases expression of SERPIN E1 (adipokines in keratinocytes), mainly in dry skin, induced by release of natriuretic polypeptide b (NPPB) in the nerve endings. Calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) and substance P (SP) are also overexpressed.

Antimicrobial peptides participate in cutaneous neuropoiesis. Cathelicidin LL-37 increases expression of semaphorin A, and β-defensins inhibit production of growth factors such as NGF or artemin.6 They also induce secretion of pruritogenic cytokines such as IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31. This neuroinflammatory environment—cutaneous hyperinnervation and disproportionate excitation of nerve endings—gives rise to sensitization to pruritus in patients with AD, marked by hyperactivity of the thalamus, prefrontal cortex, and cingulate cortex.7,8

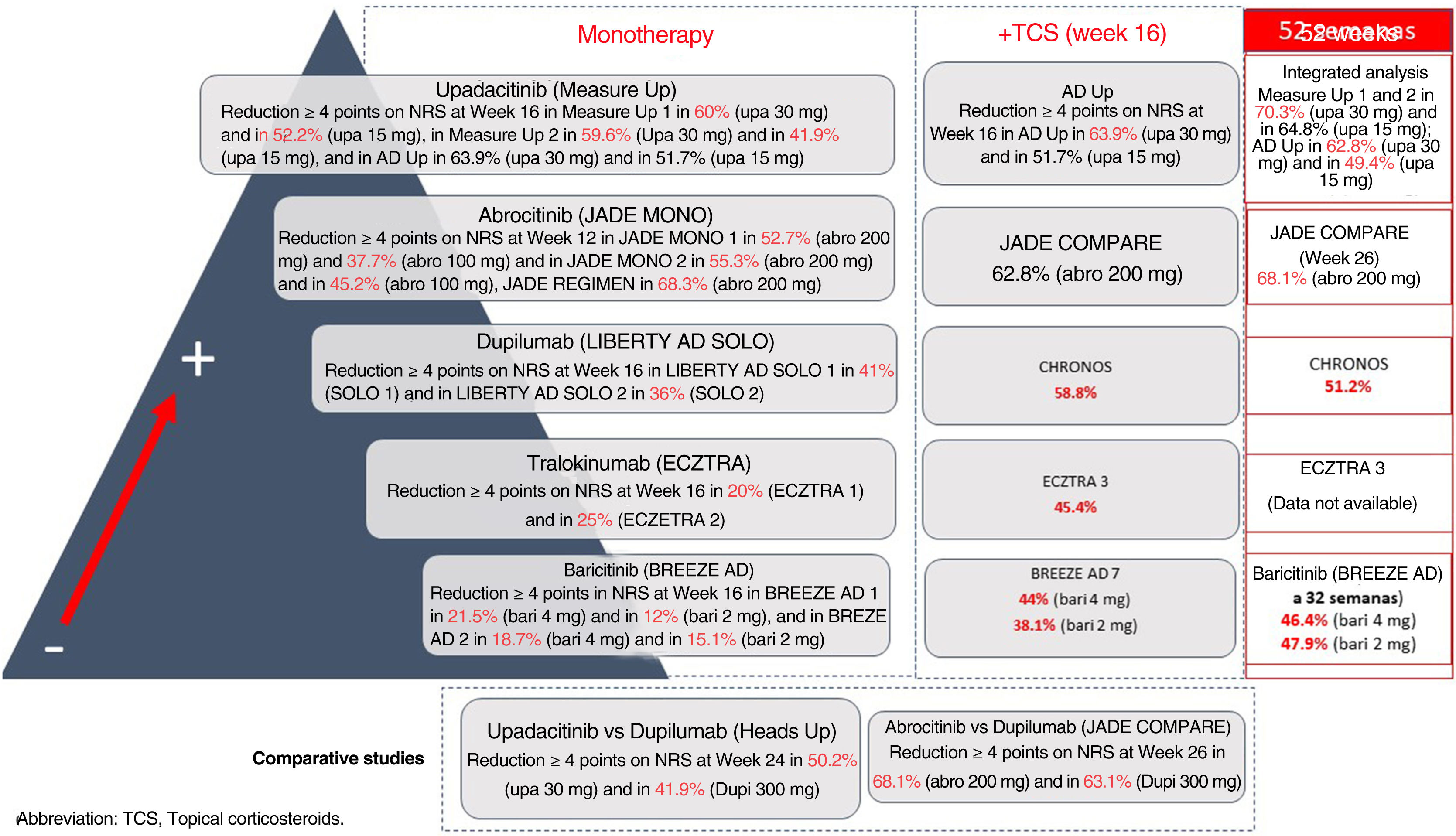

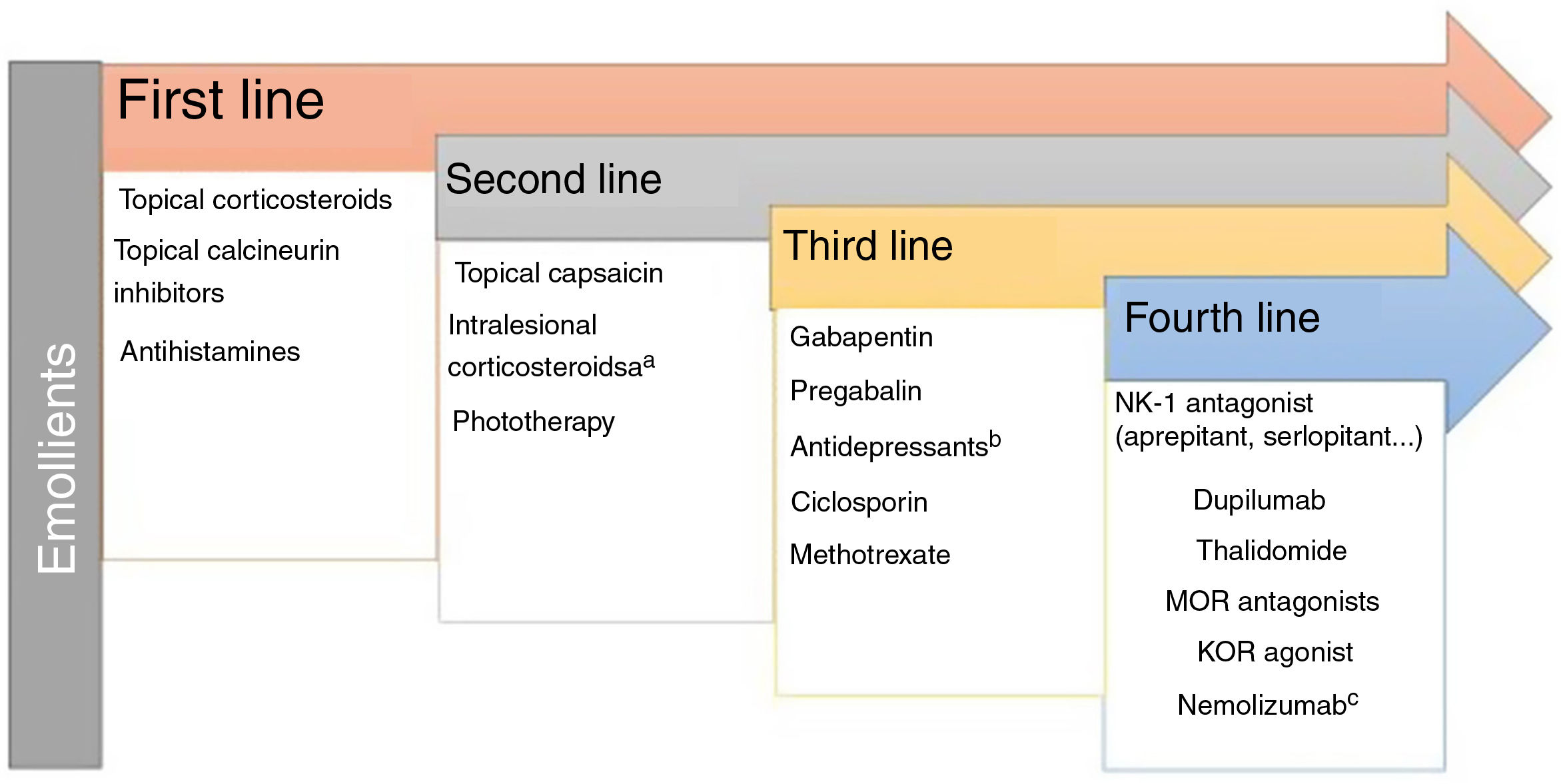

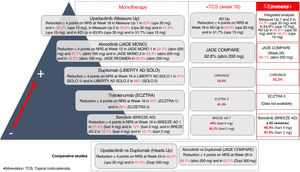

It is a complex task to compare results on improvement in pruritus across the different trials of these new molecules for the treatment of AD. These treatments are detailed in Fig. 1. Oral upadacitinib showed the best results in monotherapy and in combination with corticosteroids, and at 52 weeks. A study has been published of dupilumab with 4-year data, with an improvement in NRS≥4 with respect to baseline in 69% of patients,9 and with tralokinumab at 3 years in 58% of patients (data not published). Lebrikizumab, which is not included as it is not available commercially, showed a ≥4-point reduction in NRS at 16 weeks in 70% of patients.10 Treatment of pruritus in patients with AD is still considered an unmet need, where combination with NK-1R and GABAergic antagonists, and even opioid derivatives may break the itch-scratch cycle and achieve an NRS of 0–1.

Allergic Contact DermatitisThe chemokine, IFNγ inducible protein 10 (CXL10), has been linked with pruritus in allergic contact dermatitis.11 IL-31 and TSLP also act as pruritogens. Overexpression of MrgprX2 has been detected. Allergens are able to induce different inflammatory responses.12 Fragrances trigger the type 2 inflammatory pathway, whereas nickel and isothiazolinones induce the type 1 pathway. This raises the possibility of targeted therapy with molecules such as dupilumab, for example.

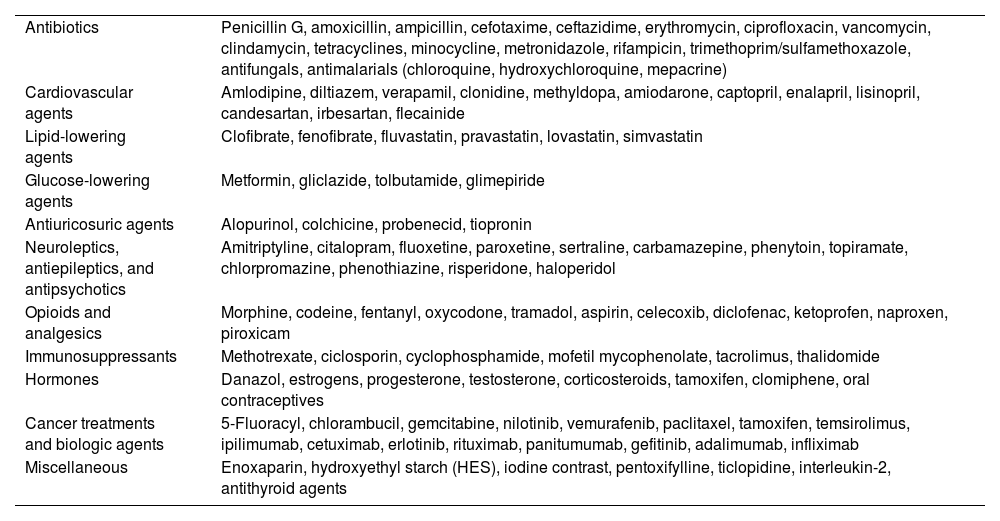

Drug-Induced PruritusApproximately 5% of cases of pruritus are caused by drugs. This may be through pruritogenic metabolites, photodermatoses, liver toxicity, or xerosis. Table 1 lists the main pruritus-inducing drugs.13

Main Drugs Associated with Triggering Pruritus.

| Antibiotics | Penicillin G, amoxicillin, ampicillin, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, vancomycin, clindamycin, tetracyclines, minocycline, metronidazole, rifampicin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, antifungals, antimalarials (chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, mepacrine) |

| Cardiovascular agents | Amlodipine, diltiazem, verapamil, clonidine, methyldopa, amiodarone, captopril, enalapril, lisinopril, candesartan, irbesartan, flecainide |

| Lipid-lowering agents | Clofibrate, fenofibrate, fluvastatin, pravastatin, lovastatin, simvastatin |

| Glucose-lowering agents | Metformin, gliclazide, tolbutamide, glimepiride |

| Antiuricosuric agents | Alopurinol, colchicine, probenecid, tiopronin |

| Neuroleptics, antiepileptics, and antipsychotics | Amitriptyline, citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, carbamazepine, phenytoin, topiramate, chlorpromazine, phenothiazine, risperidone, haloperidol |

| Opioids and analgesics | Morphine, codeine, fentanyl, oxycodone, tramadol, aspirin, celecoxib, diclofenac, ketoprofen, naproxen, piroxicam |

| Immunosuppressants | Methotrexate, ciclosporin, cyclophosphamide, mofetil mycophenolate, tacrolimus, thalidomide |

| Hormones | Danazol, estrogens, progesterone, testosterone, corticosteroids, tamoxifen, clomiphene, oral contraceptives |

| Cancer treatments and biologic agents | 5-Fluoracyl, chlorambucil, gemcitabine, nilotinib, vemurafenib, paclitaxel, tamoxifen, temsirolimus, ipilimumab, cetuximab, erlotinib, rituximab, panitumumab, gefitinib, adalimumab, infliximab |

| Miscellaneous | Enoxaparin, hydroxyethyl starch (HES), iodine contrast, pentoxifylline, ticlopidine, interleukin-2, antithyroid agents |

This is primarily a histamine-mediated pruritus where mastocytes and basophils orchestrate the process. Recently, IL-414 and CGRP have been recognized as pruritogenic mediators in urticaria. New targets such as Mrgpr,15 Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK),16 and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK),17 appear to be promising. Dupilumab has shown significant results for this condition,18 as have biologic agents that target IL-5.19

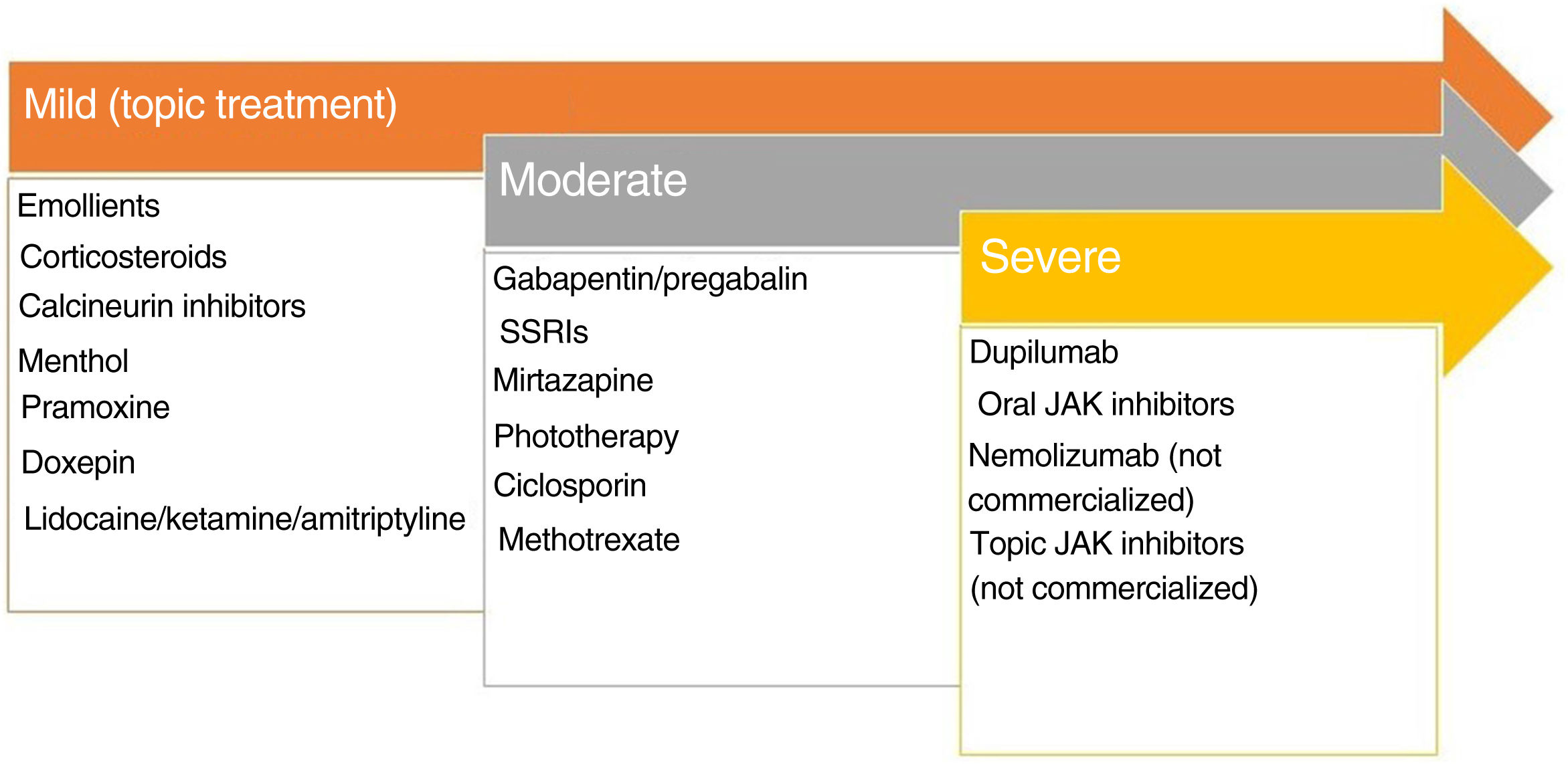

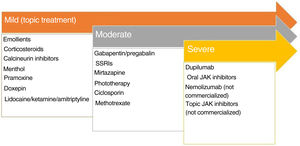

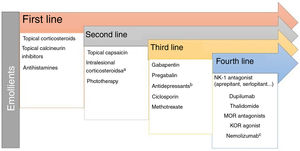

Lichen Simplex ChronicusIn this disease, expression of GRPR+ neurons and TRPV1 and PTRA1 is increased. A small fiber neuropathy caused by decreased expression of NGF has been considered.20 Chronic scratching induces the release of pruritogens by keratinocytes following direct damage to the epidermal barrier. The inflammatory infiltrate is predominantly type 2. IL-31 is the cytokine responsible for the chronic status of pruritus. The recommended treatments are presented in Fig. 2.

PsoriasisBetween 60% and 90% of patients report pruritus.21 There is overexpression of SP, TSLP, and IL-31,22 while expression of KOR/dynorphin and NPY is reduced. CGRP participates in the induction of pruritus at the nerve endings. Dorsal root ganglion neurons express IL-17 receptors.23 Up to 70% of patients treated with ixekizumab show a reduction in pruritus.24 Bimekizumab achieved a pruritus score of 0 on the P-SIM scale in 32.2% of patients at Week 16 and in 60% of patients at Week 48.25 IL-22 appears to activate GPRP+ neurons and enhance the pruritogenic signal. Those patients with refractory pruritus may obtain clinical benefit from NK-1 receptor antagonists or opioid derivatives.

Mycosis Fungoides/Sezary SyndromeUp to 88% of patients with these conditions report pruritus,26 which is considered a factor for worse prognosis. It is more frequent in variants such as the folliculotropic one,27 and in advanced stages of the disease. IL-31 and SP are the main pruritogens. High levels of IL-4, IL-2, and IFNγ have been detected in Sezary syndrome.28 A certain polarization toward Th2 has been reported, and this could explain the eosinophilia (factor for worse prognosis).29 However, patients treated with dupilumab have shown a worsening of the disease.30 Other mediators involved are PAR2 and GRPR+ neurons, while an MOR/KOR imbalance may also occur.27 Aprepitant31 has shown significant results in the reduction of pruritus (regimen 125-80-80mg/every 2 weeks). Mirtazapine, GABAergic agents, opioid agents, and thalidomide can be considered as additions to the base treatment.

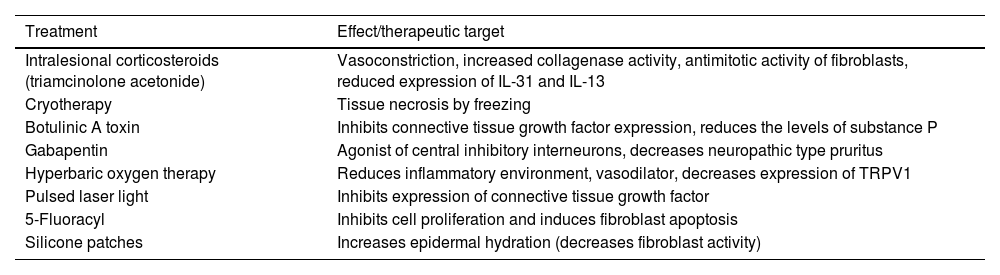

Pruritus in Keloid ScarsTranscriptomic techniques have demonstrated an inflammatory neurogenic microenvironment, with predominance of Th2 lymphocytes and mastocytes. NGF and SP are overexpressed, and IL4Rα, tryptase, and periostin levels are elevated.32 Polarization of macrophages toward M2 enhances the type 2 inflammatory response, triggering secretion of TGF-β by fibroblasts, which in turn induce IL-31 release. Thermal sensitivity tests have shown an alteration in the C fibers. There is a decreased density of intraepidermal fibers. Both phototherapy33 and dupilumab34 significantly decrease pruritus. Table 2 shows the different treatments available.

Treatments Available for Pruritus in Keloid Scars.

| Treatment | Effect/therapeutic target |

|---|---|

| Intralesional corticosteroids (triamcinolone acetonide) | Vasoconstriction, increased collagenase activity, antimitotic activity of fibroblasts, reduced expression of IL-31 and IL-13 |

| Cryotherapy | Tissue necrosis by freezing |

| Botulinic A toxin | Inhibits connective tissue growth factor expression, reduces the levels of substance P |

| Gabapentin | Agonist of central inhibitory interneurons, decreases neuropathic type pruritus |

| Hyperbaric oxygen therapy | Reduces inflammatory environment, vasodilator, decreases expression of TRPV1 |

| Pulsed laser light | Inhibits expression of connective tissue growth factor |

| 5-Fluoracyl | Inhibits cell proliferation and induces fibroblast apoptosis |

| Silicone patches | Increases epidermal hydration (decreases fibroblast activity) |

Abbreviations: IL-13, interleukin-13; IL-31, interleukin-31; TRPV1, transient receptor potential vanilloid 1.

Up to 57% of patients with connective tissue diseases are affected by pruritus, as a result of pruritogen release or triggering/worsening by intake of drugs such as antimalarials or calcium antagonists.

- A.

Dermatomyositis (DM): Up to 90% of patients with DM are affected by pruritus,35 mainly in photoexposed areas. The severity of pruritus correlates with the severity of DM. There are no differences between the classic and amyopathic form. It appears as a premonitory form, during the disease, or as a paraneoplastic condition. IL-31 has been identified as a pruritogen.36 Reduction in intraepidermal nerve fibers without any changes in peptidergic fibers points to a possible small fiber neuropathy.37

- B.

Systemic sclerosis: Pruritus occurs in 62.3% of patients with this disease.38 It shows neuropathic characteristics and presents mainly on the head, trunk, and arms. Patients with pruritus show greater skin, gastrointestinal, and/or pulmonary involvement. The chronic nature of pruritus is related to the presence of anti-centromere antibodies.39 A regeneration of C fibers and an increase in the neuronal population occur.

- C.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: Of patients with this disease, 76.8% are affected by pruritus, which is of moderate or severe intensity in half of these.40 The scalp is the most common site. A decrease in the number of small fibers and a decrease in intraepidermal nerve fibers have been detected.41 Photosensitivity and use of antimalarial agents are trigger factors. These patients show high levels of IL-31.42

- D.

Morphea: Between 46% and 52.2% of patients with morphea experience pruritus,43 which is more prevalent in adults than in children. Improvement with phototherapy suggests a cytokine-mediated neurogenic inflammation.

- E.

Sjögren syndrome: Between 38.3% and 41.6% of patients with this syndrome also experience pruritus,44 particularly with the primary form. It is the second most common skin manifestation after xerosis. It has been described as a small fiber neuropathy.45 Paraneoplastic pruritus should be considered given the risk of lymphomas and thyroid cancer.46

The recommended treatments for pruritus in these patients are apremilast, gabapentin, pregabalin, naltrexone, and thalidomide as an addition to the base treatment. Oral and topical JAK inhibitors appear promising.

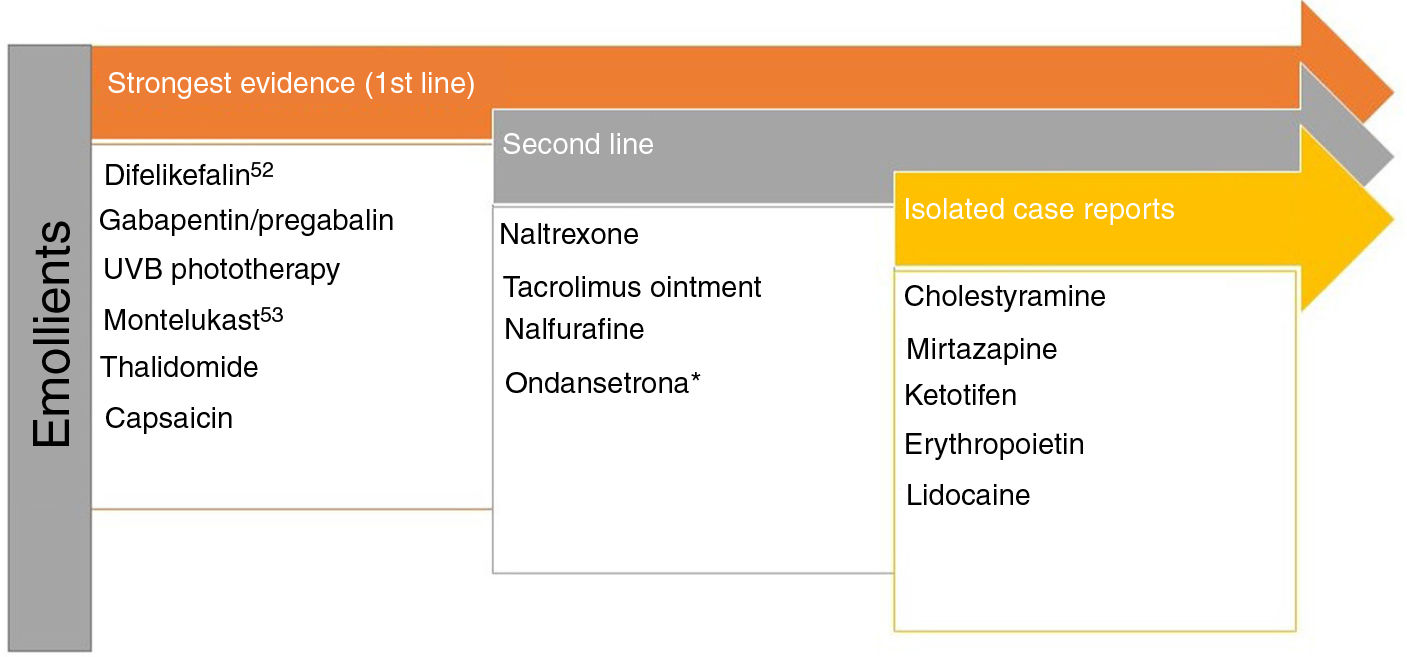

Pruritus and Chronic Kidney DiseaseModerate to severe pruritus is present in 38.2% of patients on hemodialysis,47 with mortality as high as 17%.48 There are 4 theories to explain this type of pruritus49: toxin build-up, peripheral neuropathy, immune system dysregulation, and opioid imbalance. Recently, p-cresyl sulfate and indoxyl sulfate have been proposed as 2 uremic toxins that could be implicated in both pruritus and cardiovascular risk.50Fig. 3 shows the recommended treatments.51–53

Treatments recommended for pruritus in kidney disease. a Although expert panels continue to recommend ondansetron as second-line therapy, the most recent Cochrane review concludes that it is not an effective drug in the treatment of uremic pruritus.53

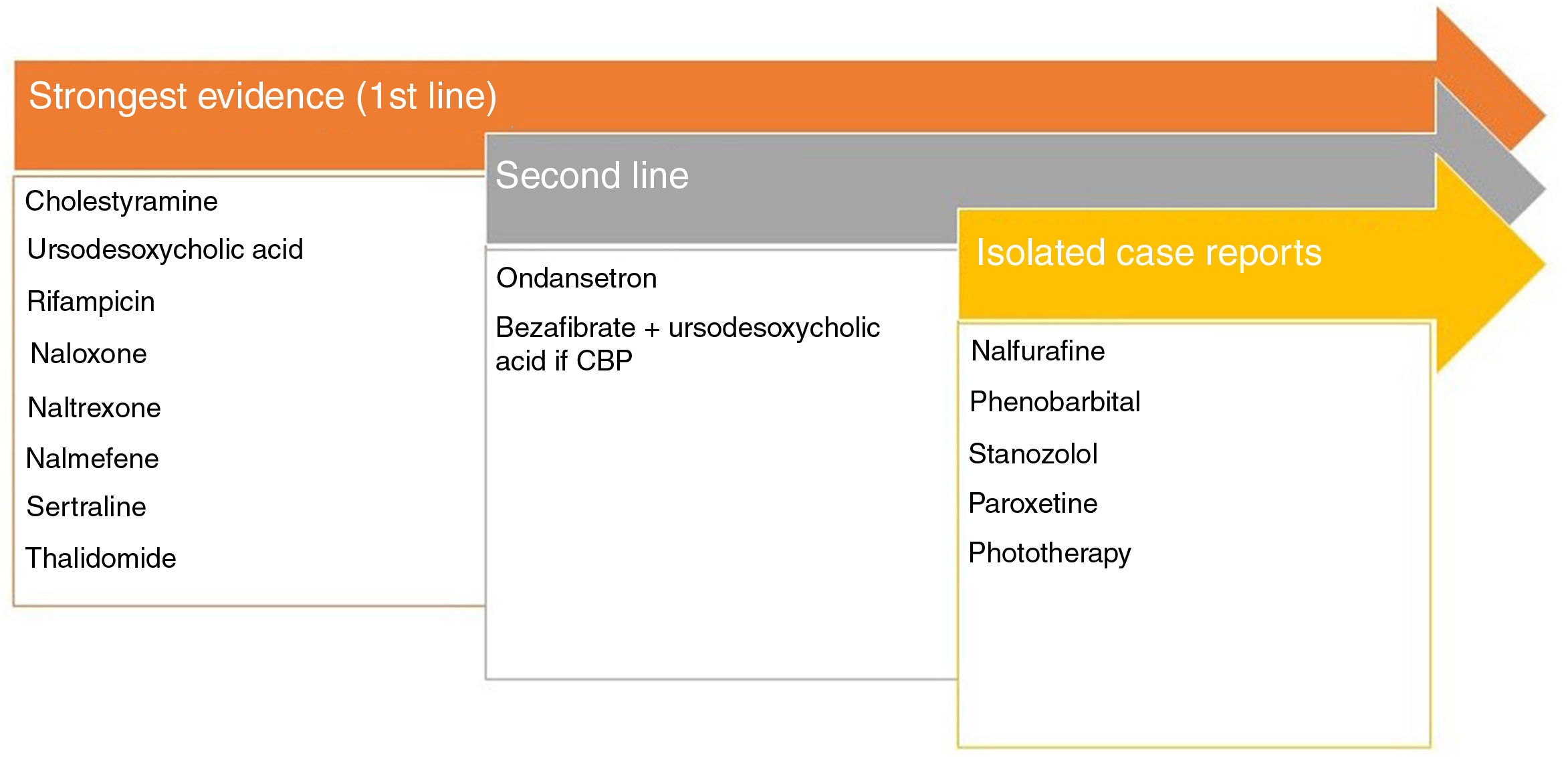

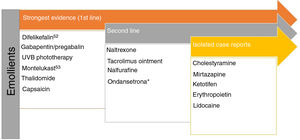

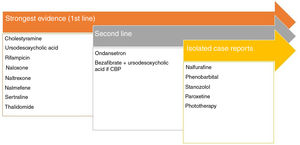

This pruritus presents at palmoplantar sites, although it can be generalized. Primary biliary cirrhosis or primary sclerosing cholangitis show elevated levels of autotaxin,54 an enzyme that metabolizes lysophosphatidylcholine into lysophosphatidic acid able to activate TRPV4. Naltrexone has been shown to be effective in uremic pruritus.55 The most important pruritogenic pathway is binding of bile acids to MrgprX4.56 Rifampicin decreases the activity of autotaxin.57Fig. 4 shows the recommended treatments.

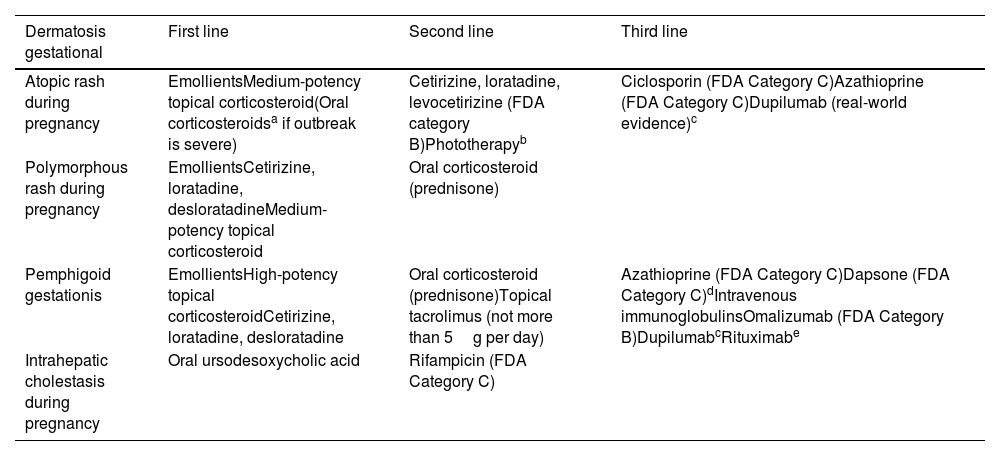

Pruritus and PregnancyBetween 18% and 40% of pregnant women experience pruritus at some point during gestation.58 Some of the most important types are summarized below.59Table 3 shows the different treatments available.

- A.

Atopic rash during pregnancy: This is the most frequent type. A history of AD is present in 20%. Type 2 inflammation predominates. Onset is usually during the second/third trimester. There are 2 main forms of presentation: eczematous form localized on the face, neck, presternal region, and flexural areas; and the prurigo type on extension surfaces and the trunk. There is a risk of infectious complications such as eczema herpeticum. There is no risk to the fetus.

- B.

Polymorphous rash during pregnancy: This is a self-limiting process with pruritic urticarial papules and plaques. Onset is usually during the third trimester or immediately postpartum. The eczematous lesions are located on the abdomen (over stretch marks if present) and the periumbilical region, without blistering. The rash may be confused with an initial state of pemphigoid gestationis. There is no risk to the fetus.

- C.

Pemphigoid gestationis: This is an uncommon self-limiting disease caused by IgG autoantibodies to the BP180 protein. Recurrence in successive pregnancies is 30–50%, with an early and severe onset. Polymorphic urticarial papules and plaques form on the periumbilical region, abdomen, and limbs. The mucosa may be involved. Biopsy with IFD shows linear deposition of IgG and C3 at the dermoepidermal junction. The antibodies can be detected by ELISA (specificity 94–98%; sensitivity 86–97%). This is considered a high-risk pregnancy. There is a risk to the fetus.

- D.

Intrahepatic cholestasis: This affects 0.3–5.6% of pregnant women. Bile salts are the main pruritogen. Onset occurs during the second/third trimester through activation of the MrgprX4 receptor. Measurement of bile acids in maternal blood is the key to diagnosis. If the concentration of bile acids in blood is >100mmol/L and 37 weeks of gestation have been completed, induction of pregnancy can be considered. There is a risk to the fetus.

- E.

Dermatoses that worsen during pregnancy: AD, psoriasis, dermatomyositis, urticaria, lichen planus, mastocytosis can all worsen during pregnancy.

Recommended Treatments for Different Gestational Dermatoses that Present with Pruritus.

| Dermatosis gestational | First line | Second line | Third line |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atopic rash during pregnancy | EmollientsMedium-potency topical corticosteroid(Oral corticosteroidsa if outbreak is severe) | Cetirizine, loratadine, levocetirizine (FDA category B)Phototherapyb | Ciclosporin (FDA Category C)Azathioprine (FDA Category C)Dupilumab (real-world evidence)c |

| Polymorphous rash during pregnancy | EmollientsCetirizine, loratadine, desloratadineMedium-potency topical corticosteroid | Oral corticosteroid (prednisone) | |

| Pemphigoid gestationis | EmollientsHigh-potency topical corticosteroidCetirizine, loratadine, desloratadine | Oral corticosteroid (prednisone)Topical tacrolimus (not more than 5g per day) | Azathioprine (FDA Category C)Dapsone (FDA Category C)dIntravenous immunoglobulinsOmalizumab (FDA Category B)DupilumabcRituximabe |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis during pregnancy | Oral ursodesoxycholic acid | Rifampicin (FDA Category C) |

Oral glucocorticoids 0.5–2mg/kg/day with particular care during the first trimester. Use in uncontrolled pruritus for a short period of time. It has been associated with cleft palate and low weight at birth. It increases the risk of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and premature birth with premature breaking of water.

During treatment with phototherapy, it is necessary to administer folic acid supplement 0.8mg/day because this treatment reduces levels of folic acid in blood. Facial photoprotection is recommended to avoid melasma.

The current experience is from real clinical practice, and although data show that dupilumab is a safe drug during gestation, experts recommend an individual benefit-risk assessment in each patient.

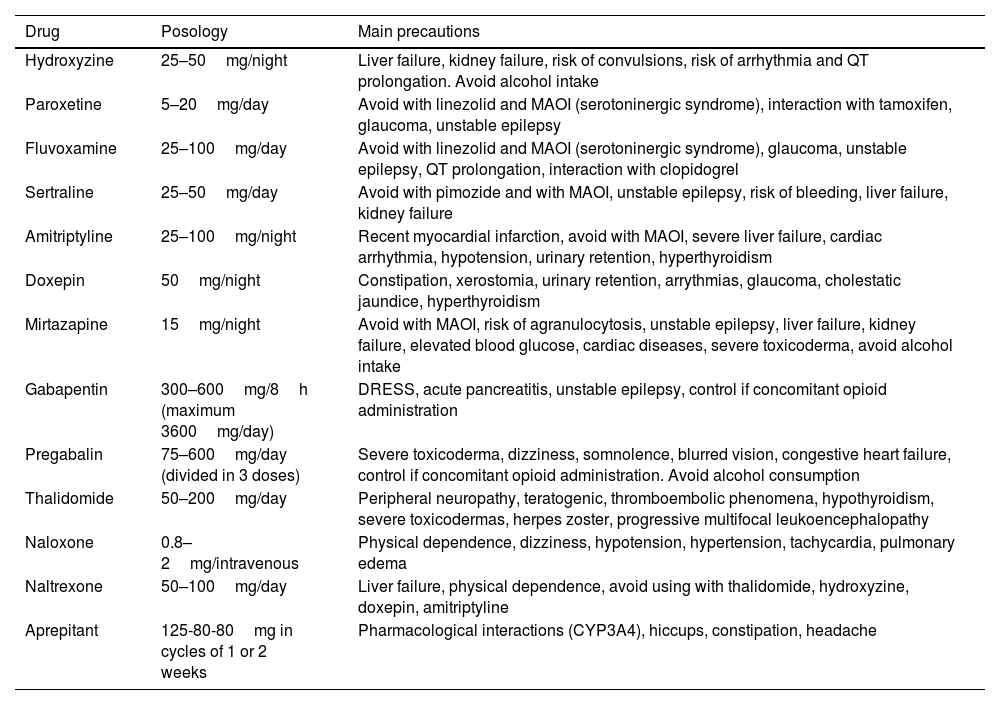

Pruritus that has an onset before or during the tumor process but that is not the result of either infiltration by tumor cells or treatment administered is denoted paraneoplastic pruritus.60 It resolves after tumor remission and reappears if there is recurrence. Hematologic neoplastic and gastrointestinal disorders are the most frequent neoplasms where this occurs. In up to 5.9% of cases, pruritus is generalized. Thirty percent of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma, 40% with essential thrombocytosis, and 15–50% of those with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and polycythemia vera (with characteristic aquagenic pruritus,61 more severe in carriers of the JAK2 V617F mutation), also have pruritus. Table 4 shows the different treatments available.

Recommended Treatment for Paraneoplastic Pruritus. Bear in Mind Precautions to Ensure Appropriate Selection of the Patient Profile.

| Drug | Posology | Main precautions |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyzine | 25–50mg/night | Liver failure, kidney failure, risk of convulsions, risk of arrhythmia and QT prolongation. Avoid alcohol intake |

| Paroxetine | 5–20mg/day | Avoid with linezolid and MAOI (serotoninergic syndrome), interaction with tamoxifen, glaucoma, unstable epilepsy |

| Fluvoxamine | 25–100mg/day | Avoid with linezolid and MAOI (serotoninergic syndrome), glaucoma, unstable epilepsy, QT prolongation, interaction with clopidogrel |

| Sertraline | 25–50mg/day | Avoid with pimozide and with MAOI, unstable epilepsy, risk of bleeding, liver failure, kidney failure |

| Amitriptyline | 25–100mg/night | Recent myocardial infarction, avoid with MAOI, severe liver failure, cardiac arrhythmia, hypotension, urinary retention, hyperthyroidism |

| Doxepin | 50mg/night | Constipation, xerostomia, urinary retention, arrythmias, glaucoma, cholestatic jaundice, hyperthyroidism |

| Mirtazapine | 15mg/night | Avoid with MAOI, risk of agranulocytosis, unstable epilepsy, liver failure, kidney failure, elevated blood glucose, cardiac diseases, severe toxicoderma, avoid alcohol intake |

| Gabapentin | 300–600mg/8h (maximum 3600mg/day) | DRESS, acute pancreatitis, unstable epilepsy, control if concomitant opioid administration |

| Pregabalin | 75–600mg/day (divided in 3 doses) | Severe toxicoderma, dizziness, somnolence, blurred vision, congestive heart failure, control if concomitant opioid administration. Avoid alcohol consumption |

| Thalidomide | 50–200mg/day | Peripheral neuropathy, teratogenic, thromboembolic phenomena, hypothyroidism, severe toxicodermas, herpes zoster, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

| Naloxone | 0.8–2mg/intravenous | Physical dependence, dizziness, hypotension, hypertension, tachycardia, pulmonary edema |

| Naltrexone | 50–100mg/day | Liver failure, physical dependence, avoid using with thalidomide, hydroxyzine, doxepin, amitriptyline |

| Aprepitant | 125-80-80mg in cycles of 1 or 2 weeks | Pharmacological interactions (CYP3A4), hiccups, constipation, headache |

Abbreviations: DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; MAOI, monoaminooxidase inhibitors.

T lymphocytes, mastocytes, and eosinophils in histopathology studies confirm the type 2 inflammatory environment, where cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-31 appear to play an important role, as well as IL-17 and IL-22.62 Overexpression of SP+ and CGRP+ peptidergic neurons has been detected. There is dermal hyperinnervation and a reduction in the density of epidermal nerve fibers as a result of an imbalance between neuronal growth factors and repulsion factors.63 Although JAK inhibitors have not been included in Fig. 5, a case report was recently published of good response to baricitinib.64 Therapies that target IL-31 have been demonstrated to be effective.65 Nemolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to the IL-31α receptor.66 AD and prurigo nodularis are the main therapeutic focus. The results of the phase 3 study for AD showed a decrease of 42.8% (in combination with topical corticosteroids) in the pruritus score at 16 weeks compared with baseline (in the placebo arm, the reduction was 20%).67 The results of the phase 2 study of prurigo nodularis showed a decrease of 53% at Week 4 (compared with 20.2% in the placebo group).68 Vixarelimab (KPL-716)69 is a subcutaneously administered monoclonal antibody that binds to OSMRβ. A phase 2 study of prurigo nodularis is currently active (but not recruiting).

Pruritus and Bullous PemphigoidThis is characterized by predominance of a type 2 inflammatory environment, the intensity of which correlates with dermal periostin build-up and infiltrates of eosinophils, basophils, and Th2 lymphocytes. IL-4 and IL-31 act as pruritogens. Dupilumab has been shown to be effective in this type of dermatosis.70

Anogenital PruritusThis type of pruritus can be a manifestation of either a local dermatosis or a systemic one.71 The acute forms are more common in association with infections and contact dermatitis whereas the chronic ones are psychogenic, neoplastic, or chronic inflammatory dermatoses. Detailed medical history and targeted additional tests are key to ensure an appropriate therapeutic approach. The area requires special care with sitz baths, avoiding the use of toilet paper, drying of the area without intense friction, avoiding wet wipes and other disinfectants, short fingernails, avoiding coffee, chocolate, citric fruits, soft drinks and food rich in dairy products, and the use of zinc oxide 10–20% powders several times a day.

Treatment of the underlying cause, application of topical corticosteroids, topical calcineurin inhibitors, antifungal agents, local anesthetics such as lidocaine, and even topical capsaicin 0.006% are some of the recommendations. The use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (sertraline, paroxetine, fluoxetine), amitriptyline, doxepin, mirtazapine, or injection of methylene blue 0.5–1% is reserved for refractory cases.72 Physiotherapy targeting the pelvic flood may be a useful option for idiopathic female genital pruritus.

Basic (General) Care of the Patient with Pruritus- -

Avoid smoking, alcohol, caffein and other stimulants, spices, and stress.

- -

Showering is better than taking a bath, with warm water and for 10min at most.

- -

Shower with detergent-free soap (Syndet), shower oils, or cleansing cream. Avoid the use of perfumed products and irritative substances such as sodium lauryl sulfate. Likewise, preferably use pH neutral soaps.

- -

Emollient creams or hypoallergenic salves, free of fragrances and preservatives with a high sensitization potential such as isothiazolinones. The ingredients may include soothing ingredients (see below).

- -

Soft and loose-fitting cotton clothing; avoid synthetic and tight-fitting materials.

Menthol 1% lotion applied 3–4 times a day (acts via the TRPM8 pathway73). In patients over 2 years of age, the following options are available:

- -

Topical anesthetics: Application to localized not too extensive areas due to risk of systemic effects. It is necessary to take care with sensitization to these products.

- -

Polidocanol 2–10% is a nonionic surfactant used in sclerotherapy with moisturizing and anesthetic properties.

- -

Compounded formulation of lidocaine 2.5–5%+amitriptyline 5%+ketamine 5–10% o/w cream74 for transdermal application. Apply 3 times/day, never to more than 30% of the body surface area.

- -

Pramoxine 1% lotion, cream, foam, gels. Apply 3–4 times a day.

- -

Lidocaine 2–5%. Apply 2–4 times a day. Take care with the possibility of methemoglobinemia if high doses of Emla® (lidocaine+procaine) are applied in young patients.

Topical antihistamines are not recommended in children.

- -

Diphenhydramine 1–2%, 3–4 times a day. Photosensitivity and urticaria due to sensitization are the most common adverse effects.

- -

Doxepin 5% cream 4 times a day, with at least 3–4 hours between applications. Risk of contact dermatitis, anticholinergic effects of local sensation of burning/itching. Should not be applied to more than 10% of the body surface area.

Topical anti-inflammatory agents and capsaicin:

- -

Topical corticosteroids: These can be applied with wet bandages or injected (triamcinolone acetonide) in the case of thick lesions. High potency corticosteroids are associated with greater risk of stretch marks and suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis.

- -

Topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCI): Tacrolimus and pimecrolimus. Application twice a day. Pruritus or a local burning sensation may present during the first applications. This sensation can be reduced with the administration of acetylsalicylic acid 500mg, initially, and by avoiding alcohol consumption during treatment.

- -

Capsaicin 0.025% cream75: Repeated application (3–4 times a day, tolerance is improved by applying Emla® 30–60min earlier) induces TRPV1 activation with subsequent SP depletion, desensitizing the nerve fibers. It is indicated in neuropathic pruritus (notalgia paresthetica, brachioradial pruritus, postherpetic pruritus). It can also be used in aquagenic or uremic pruritus and prurigo nodularis.

These are drugs that target the H1 receptor by competing with histamine. They are recommended as first-line treatment in most situations. Cetirizine and rupatadine inhibit PAF action,76 cetirizine and desloratadine decrease IL-4 and IL-13 secretion,77 fexofenadine inhibits tryptase release, and ebastine inhibits the Th2-lymphocyte mediated inflammatory pathway.78

PhototherapyBoth narrow-band (NB) UVB (311mm) and UVA (340–400mm) are considered second-line treatments in many dermatoses with associated pruritus. UVA1 decreases levels of IL-4, IL-13, IL-17 and IL-23.79 Repeated exposure to sub-erythematogenic doses both of UVA1 and NB-UVB decrease IL-31 concentration, whereas high doses have the opposite effect, in particular with UVB. A decrease has been demonstrated in degranulation of IgE-dependent mastocytes and a decrease in migration of Langerhans cells to the epidermis. Another finding is decreased expression of MOR and increased expression of dynorphin with phototherapy. Phototherapy plays a neuromodulatory role, decreasing release of NGF while increasing release of semaphorin A, giving rise to a decreased density of intraepithelial nerve fibers.80 Excimer lamps also decrease the density of intraepithelial nerve fibers.

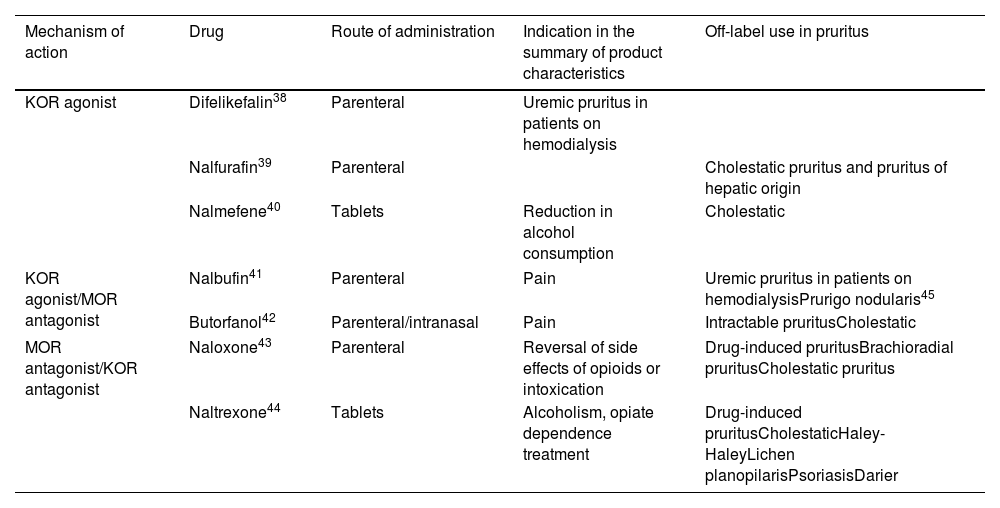

Opioid DerivativesThe mu opioid receptor (MOR) antagonists and the kappa opioid receptor (KOR) agonists have been shown to be very useful given their role as central pruritus regulators. Table 581–89 shows detailed information on this useful antipruritic therapy.

Opioids, Mechanism of Action, and Uses in Pruritus.

| Mechanism of action | Drug | Route of administration | Indication in the summary of product characteristics | Off-label use in pruritus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KOR agonist | Difelikefalin38 | Parenteral | Uremic pruritus in patients on hemodialysis | |

| Nalfurafin39 | Parenteral | Cholestatic pruritus and pruritus of hepatic origin | ||

| Nalmefene40 | Tablets | Reduction in alcohol consumption | Cholestatic | |

| KOR agonist/MOR antagonist | Nalbufin41 | Parenteral | Pain | Uremic pruritus in patients on hemodialysisPrurigo nodularis45 |

| Butorfanol42 | Parenteral/intranasal | Pain | Intractable pruritusCholestatic | |

| MOR antagonist/KOR antagonist | Naloxone43 | Parenteral | Reversal of side effects of opioids or intoxication | Drug-induced pruritusBrachioradial pruritusCholestatic pruritus |

| Naltrexone44 | Tablets | Alcoholism, opiate dependence treatment | Drug-induced pruritusCholestaticHaley-HaleyLichen planopilarisPsoriasisDarier | |

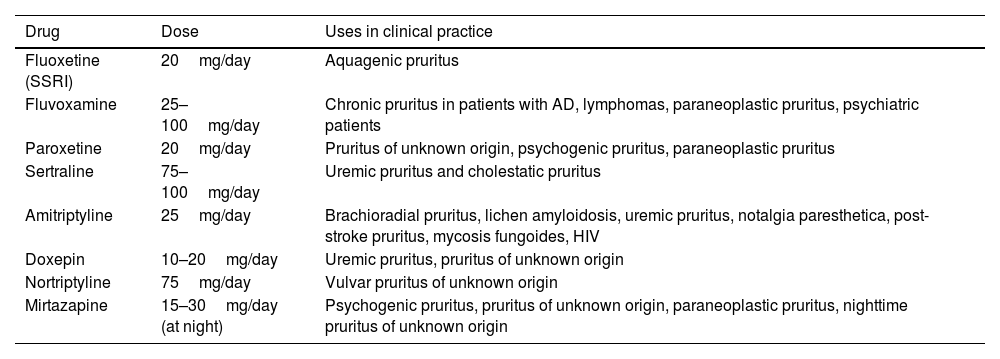

Results have been published for uremic, cholestatic, or paraneoplastic pruritus. The peak of the effect is reached after 4–6 weeks. Side effects limit their use, particularly in the case of SSRIs and mirtazapine. These agents are less effective than pregabalin or gabapentin in neuropathic pruritus. The results of an analysis of 35 studies are shown in Table 6.90

Main Antidepressants Used for Treatment of Pruritus.

| Drug | Dose | Uses in clinical practice |

|---|---|---|

| Fluoxetine (SSRI) | 20mg/day | Aquagenic pruritus |

| Fluvoxamine | 25–100mg/day | Chronic pruritus in patients with AD, lymphomas, paraneoplastic pruritus, psychiatric patients |

| Paroxetine | 20mg/day | Pruritus of unknown origin, psychogenic pruritus, paraneoplastic pruritus |

| Sertraline | 75–100mg/day | Uremic pruritus and cholestatic pruritus |

| Amitriptyline | 25mg/day | Brachioradial pruritus, lichen amyloidosis, uremic pruritus, notalgia paresthetica, post-stroke pruritus, mycosis fungoides, HIV |

| Doxepin | 10–20mg/day | Uremic pruritus, pruritus of unknown origin |

| Nortriptyline | 75mg/day | Vulvar pruritus of unknown origin |

| Mirtazapine | 15–30mg/day (at night) | Psychogenic pruritus, pruritus of unknown origin, paraneoplastic pruritus, nighttime pruritus of unknown origin |

Abbreviations; AD, atopic dermatitis; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

There are more publications and information in the case of refractory prurigo nodularis.91 The thalidomide dose is 50–300mg/day, with an average dose of 100mg/day, followed by NB-UVB phototherapy. It has a good profile in oncology patients and those with HIV. The main drawbacks are teratogenicity and neuropathy. Lenalidomide is an interesting option given its low cost and lower rate of neuropathy.

Apremilast/Difamilast/RoflumilastApremilast is indicated for psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and Behçet disease. It has not shown significant results either in AD or pruritus of unknown origin.92 Difamilast ointment is in development for AD.93 Off-label use of oral roflumilast has been reported for nummular eczema94 and hidradenitis suppurativa.95 Roflumilast cream is in development for psoriasis.96

AntineuralgicsThe gamma aminobutyric acid analogs, gabapentin and pregabalin, are recommended for neuropathic-type pruritus and brachioradial pruritus, cholestatic and uremic pruritus, and pruritus of unknown origin.97 Release of SP or CGRP is decreased,98 whereas the inhibitory capacity of GABA+ interneurons is increased. They bind to protein α2δ of the voltage-gated calcium channels. The gabapentin dose is 300mg/every 8h (maximum dose 3600mg/day) and the pregabalin dose is 75mg/day with increases up to 225mg/day according to tolerance (maximum dose 300mg/day). The dose should be tapered prior to withdrawal of the drug.

Classic ImmunosuppressantsThese agents are widely used in dermatology as corticosteroid sparing agents99 or in monotherapy. Physicians should be familiar with the particular characteristics of each of them100:

- A.

Ciclosporin: According to the Summary of Product Characteristics, this is indicated for AD in patients aged 16 years and above at doses of 3–5mg/kg/day, spread over 2–3 doses. It inhibits lymphocyte, eosinophil, and mastocyte infiltrates, inhibits NK1-R and IL-31R expression, inhibits IL-31 secretion, and inhibits intraepidermal nerve fiber elongation.101 Given its mechanism of action, neuroinflammatory pruritus is considered the type that shows best response. Up to 78% of patients treated with this drug show a reduction in pruritus.102

- B.

Methotrexate: This drug is indicated according to the Summary of Product Characteristics for psoriasis. The mean dose used is 15mg/week. The anti-inflammatory infiltrate makes it a good choice for treatment of neuroinflammatory pruritus, even at low doses. Good outcomes have been achieved in cases of pruritus of unknown origin in elderly individuals103 and in prurigo nodularis.104

- C.

Azathioprine: This agent does not include any dermatologic indications in its Summary of Product Characteristics. It has been shown to significantly reduce itching in patients with intractable pruritus105 and in primary biliary cirrhosis.

- D.

Mofetil mycophenolate: This is the prodrug of mycophenolic acid, which inhibits inosine-5-monophosphate dehydrogenase and decreases T and B lymphocyte proliferation; this may be useful in patients with neuroinflammatory pruritus as is the case in AD106 and autoimmune diseases.

Aprepitant107 is the most widely used of these agents and has the most publications on its use. It is dispensed in a 3-tablet blister (125-80-80mg). The regimen is not defined, as there are publications of cycles of 3 tablets every 1 or 2 weeks and 80mg/day. The best responses have been observed for paraneoplastic pruritus108 and pruritus induced by cancer treatments,109 although these results are disputed. Serlopitant appears to be superior to aprepitant.110 Doses of 5mg for prurigo nodularis have shown significant reductions in pruritus compared with placebo. The results of the EPIONE study with tradipitant in 2021 did not show significant results in AD,111 and it is currently under development for gastrointestinal disorders.

AntibioticsDoxycycline and minocycline: These agents exercise an antipruritic and neuroprotective effect through regulation of the microglial cell population in the intramedullary posterior horn.112 Doxycycline inhibits PAR2 implicated in pruritus mediation.

Erythromycin and azithromycin: These agents have been shown to be effective in pruritus associated with atypical forms of pityriasis rosada113 and chronic lichenoid pityriasis.114 The immunomodulatory effect is attributed to interaction with phospholipids and with the transcription factors AP-1, NFκB, and proinflammatory cytokines.

Antagonists of the Serotonin 5HT-3 ReceptorOndansetron, tropisetron, and granisetron have been used in isolated cases with contradictory results. These agents are not recommended except in pruritus associated with chronic renal disease and cholestatic pruritus.

ConclusionsBreaking the itch-scratch cycle can be a therapeutic challenge. The key to success is choosing the appropriate treatment for each patient.

Conflicts of InterestThe author declares that he has no conflicts of interest.