Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common cancer in humans and its incidence is rising. Although surgery is the treatment of choice for cSCC, postoperative adjuvant radiotherapy has an important role in local and locorregional disease control. In this review, we analyze the value of postoperative radiotherapy in the management of high-risk cSCC (in particular, cases with perineural invasion), cSCC with positive surgical margins, and locally advanced cSCC (with parotid gland and/or lymph node metastasis).

El carcinoma epidermoide cutáneo (CEC) es el segundo tumor más frecuente en humanos y tiene una incidencia creciente. Aunque la cirugía representa el tratamiento de elección del CEC, la radioterapia adyuvante postoperatoria tiene un papel relevante en el control local y locorregional de la enfermedad. En esta revisión analizamos la utilidad de la radioterapia postoperatoria en el manejo del CEC de alto riesgo (especialmente con infiltración perineural), en el control del CEC con márgenes positivos tras la cirugía y en el CEC localmente avanzado (con metástasis parotídeas o ganglionares).

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common cancer in human. Its incidence has risen in epidemic proportions in recent decades1 and is probably underestimated.2 In the United States, approximately 700 000 new cases of cSCC are diagnosed every year,2 and the lifetime risk of developing this cancer is between 7% and 11%,3 with slightly higher rates in men.4 In Spain, the estimated incidence is 38.16 cases per 100 000 person-years.5 The overall risk of metastasis in cSCC ranges between between 2% and 6%.6 The overall mortality attributable to cSCC is 2%,2 but when the disease spreads, 5-year mortality rates vary between 20% and 50%.6 cSCC accounts for most deaths attributable to skin cancer in individuals older than 85 years,2 and in some areas of the United States, death from cSCC is comparable to that from renal or oropharyngeal carcinoma or melanoma.2

Although surgery is the treatment of choice in cSCC, radiotherapy can be useful in selected cases,7 particularly when a patient cannot or chooses not to undergo surgery or has an unresectable tumor.8 Radiotherapy has proven to be useful as a first-line treatment with curative intent (radical radiotherapy), as an adjuvant to surgery, and as palliative treatment.9–14 Although it provides an alternative to surgery, it has lower cure rates and an appreciable proportion of tumors exhibiting aggressive behavior recur after treatment.7,15,16 In this review, we focus on the adjuvant role of radiotherapy in cSCC. There is some controversy on its usefulness in patients with positive margins after excision or with high-risk criteria, such as perineural invasion (PNI). We will also discuss the evidence for the use of adjuvant radiotherapy in locally advanced cSCC (i.e., cSCC with parotid gland or cervical lymph node involvement).

Introduction to RadiotherapyIonizing radiation damages DNA and primarily leads to the death of cells with the lowest degree of differentiation and the highest level of mitotic activity. To prevent damage to healthy tissue, it is essential that the therapeutic dose is deposited in the tumor. Tumor heterogeneity, histologic features (including degree of differentiation), and total cell volume are all key factors in radiocurability.17–19

The dose absorbed from ionizing radiation is measured in Grays (Gy). One Gy is equivalent to 100 cGy or 100 rads and the corresponding radiation is 1 Joule of energy absorbed per 1kg of mass of irradiated material. Radition does not cause the immediate death of cells, but rather affects their mitotic capacity and this may not occur for 2 or 3 cell cycles. It is therefore important not to prematurely assess treatment response. An assessment made after approximately 3 months can be considered to be reliable. Inactive tumor remnants can take months or even years to be totally reabsorbed, and it is therefore advisable to adopt a prudent, vigilant attitude.17,19

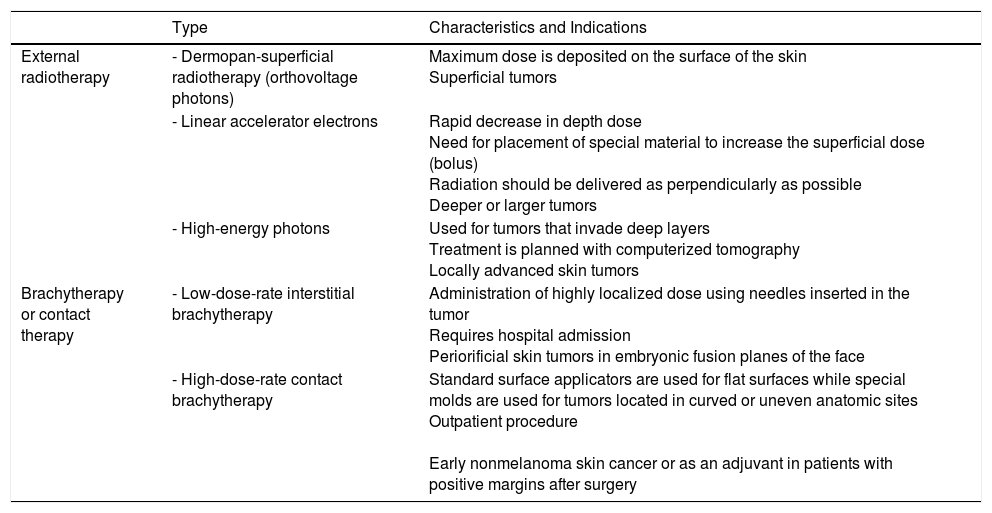

Numerous techniques, together with diverse regimens and total doses, exist for administering radiotherapy (Table 1). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guidelines for cSCC accept the use of different radiotherapy modalities (in particular external modalities) depending on the experience and availability at each center,20 as it has been demonstrated that they perform similarly in terms of effectiveness, safety, and cosmetic outcomes.21–27 Choice of technique is also influenced by tumor type, treatment intention (radical, adjuvant, or palliative), tumor depth, and anatomic location. Megavoltage radiotherapy, which is delivered by a linear accelerator, has a greater penetration capacity and is therefore useful for treating internal malignancies while largely sparing the skin. Low-energy radiation (kilovoltage and orthovoltage), is preferred when treating cutaneous lesions where deep penetration and skin preservation are not desirable. The dose of radiotherapy administered is known as a fraction. The standard fraction used in oncological dermatology is 2.5Gy administered 5 days a week, generally from Monday to Friday. Shorter regimens spanning just 2 to 3 days have been attempted, but they do not seem to offer significant advantages, as they lengthen the overall treatment time and may reduce local disease control. Hypofractionation refers to the use of higher doses (4-7Gy) per fraction, which results in a lower total dose. Hypofractionation (higher doses and fewer fractions) is useful for small lesions or for frail or elderly patients.28,29 Fractionated schedules tend to minimize long-term adverse effects, improving thus treatment effectiveness and tolerability.

Radiotherapy Modalities for Skin Cancer.

| Type | Characteristics and Indications | |

|---|---|---|

| External radiotherapy | - Dermopan-superficial radiotherapy (orthovoltage photons) | Maximum dose is deposited on the surface of the skin Superficial tumors |

| - Linear accelerator electrons | Rapid decrease in depth dose Need for placement of special material to increase the superficial dose (bolus) Radiation should be delivered as perpendicularly as possible Deeper or larger tumors | |

| - High-energy photons | Used for tumors that invade deep layers Treatment is planned with computerized tomography Locally advanced skin tumors | |

| Brachytherapy or contact therapy | - Low-dose-rate interstitial brachytherapy | Administration of highly localized dose using needles inserted in the tumor Requires hospital admission Periorificial skin tumors in embryonic fusion planes of the face |

| - High-dose-rate contact brachytherapy | Standard surface applicators are used for flat surfaces while special molds are used for tumors located in curved or uneven anatomic sites Outpatient procedure Early nonmelanoma skin cancer or as an adjuvant in patients with positive margins after surgery |

The limitations of radiotherapy include adverse effects and complications on the one hand and contraindications on the other. Skin reactions triggered by radiotherapy are referred to as radition-induced dermatitis or radiodermatitis. They can be acute or delayed. Acute reactions last for several weeks and initially consist of erythema and slight dry scaling followed by a somewhat moister scaling and mild bleeding. Delayed reactions usually appear months or years after treatment and are more common with higher treatment doses. The most common late reactions are hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation, telangiectasisas, epidermal atrophy, skin fragility, sebaceous gland atrophy, alopecia, fibrosis, necrosis, and an increased risk of certain tumors, such as angiosarcoma.30 Of note among the contradidications for radiotherapy are 1) young age, 2) verrucous squamous cell carcinoma, 3) genodermatoses with a predisposition for cancer, and 4) immunodepression.7

Another potential limitation is the cost of treatment and the need for infrastructure. The cost of treating a single cSSC ranges from $512.38 in the case of certain superficial therapies to almost $8000 for outpatient brachytherapy modalities,31 making it more expensive than conventional surgery and even Mohs micrographic surgery.32

Radiotherapy in cSCC With PNIPNI is observed in between 2.5% and 14% of cSCCs and is normally detected as an incidental histologic finding.33 It has been linked to poor prognosis and a higher rate of metastasis and disease-specific death.33–38 The risk factors in cSCC are male sex, recurrent disease, a centro-facial location, poor histologic differentiation, and deep subclinical extension.34 Although there is some evidence supporting better disease control following postoperative radiotherapy in patients with clinical PNI or cranial nerve involvement,39 this beneft is not so clear in the case of cSCC with incidental PNI.39–41

Adjuvant Radiotherapy in the Management of cSCC With Incidental Histologic PNIIncidental PNI is not uncommon in cSCC, and it is therefore necessary to evaluate the need for and benefit of postoperative (adjuvant) radiotherapy in this setting, as it is a costly treatment that is not free of adverse effects and requires multiple hospital visits by patients who are generally elderly. Incidental PNI has been associated with a risk of local recurrence (17%), lymph node metastasis (10%), distant metastasis (3%), and disease-specific death (6%).42

It has been difficult to evaluate the usefulness of postoperative radiotherapy in incidental PNI for several reasons, the main ones being the small size of the series studied to date and the difficulty of distinguishing between incidental and clinical involvement. As the results to date have been inclusive,43,44 they tend to be interpreted differently depending on the type of study. Review articles, which are generally more neutral, tend to agree on the lack of evidence supporting postoperative radiotherapy in this setting, while guidelines, which tend to take a more pragmatic approach, have traditionally opted for recommending this treatment.7,15 In cases of doubt, the recommendation is to treat, probably because of the low associated risk. There is a need for better designed studies to evaluate the indications for postoperative radiotherapy. More studies, ideally prospective, with larger numbers of patients, could help to resolve some of the doubts in this area, as could stratification of incidental PNI into subtypes in an attempt to identify the most aggressive forms. This second approach could help to determine the benefits of postoperative radiotherapy with greater ease and fewer patients.

The potential importance of the diameter of involved nerves in cSCC emerged in 2009.45 In a surprisingly small study (involving just 48 patients), Ross et al.35 showed that cSSS with invasion of nerves with a diameter of less than 0.1mm had a more favorable prognosis than tumors with invasion of larger nerves. The importance of the diameter of invaded nerves in cSCC was subsequently validated in larger series.33,46,47 The findings of these studies led to the incorporation of PNI or rather the presence of involved nerves below the dermis (as deep nerves tend to have a caliber >0.1mm) as a risk factor for staging primary tumors in the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer's Staging Manual.48,49

Although prognosis is influenced by the diameter of nerves invaded by cSCC,33,45,47 no studies have assessed the usefulness of postoperative radiotherapy according to this factor. The authors of a recent systematic review proposed using postoperative radiotherapy in cSCC with the involvement of nerves with a diameter of 0.1mm or more,42 although this recommendation was not based on studies specifically designed to address this question. In brief, the use of radiotherapy to treat cSCC with incidental PNI involving nerves with a diameter of less than 0.1mm does not appear to be justified, probably because these tumors do not exhibit aggressive behavior in the absence of radiotherapy. Finally, the usefulness of radiotherapy in cases with PNI involving large-caliber nerves remains to be demonstrated.

A number of recent studies have indicated that adjuvant radiotherapy may also be particularly useful in cSCCs with extensive PNI, defined as the involvement of more than 2 nerves, and concluded that treatment of cSCC with focal PNI (involvement of 1 or 2 nerve fibers) did not alter prognosis.39,50 The 2017 NCCN guidelines included extensive PNI as an indication for postoperative radiotherapy.20

Radiotherapy for cSCC With Clinical or Radiologic PNIInvasion of large-caliber nerves by cSCC is associated with a poor prognosis.39,42 Some patients report pain, tingling, parestesia, anesthesia, or paralysis, and these manifestations tend to be accompanied by radiologic evidence of PNI. Such tumors are classified as cSCCs with clinical PNI and have a worse prognosis (recurrence and disease-specific death) than cSCCs with incidental histologic PNI.42 The specific risks reported for tumors previously treated with radiotherapy are 37% for local recurrence, 6% for lymph node metastasis, 0.5% for distance metastasis, and 27% for disease-specific death.39

In view of the poor prognosis associated with cSCC with clinical PNI, the standard approach has been to adminster adjuvant radiotherapy, regardless of the status of the surgical margins.51,54 The level of disease control achieved in such cases, however, is always lower than that achieved in cSCC with incidental PNI.28,53–55 The use of postoperative radiotherapy to treat cSCC with clinical PNI is indicated in certain treatment guidelines.20 A recent study comparing the usefulness of neoadjuvant radiotherapy (presurgery) with that of a more conventional regimen of surgery plus postoperative radiotherapy in cSCC of the head and neck with clinical PNI found better response rates for the combined treatment.38 Patients with clinical PNI should be scheduled for follow-up visits with magnetic resonance imaging, as this is the best technique for visualizing nerve involvement.20

Radiotherapy in cSCC With Positive Margins After ExcisionBetween 5.8% and 17.6% of patients with cSCC have positive margins following excision depending on the technique used.56–64 cSCCs with a close or positive surgical margin have a higher risk of local recurrence and locoregional metastasis.65 Postoperative radiotherapy would therefore appear to be an option for tumors with incomplete margins or that cannot be fully resected. Only 1 study, however, has evaluated the impact of postoperative radiotherapy in cSCC with positive margins.66 In a study of cSCCs of the lower lip that included tumors with a close or positive margin, Babington et al.66 observed a local recurrence rate of 64% for tumors with positive margins that were not re-excised versus a rate of just 6% for those treated with postoperative radiotherapy.

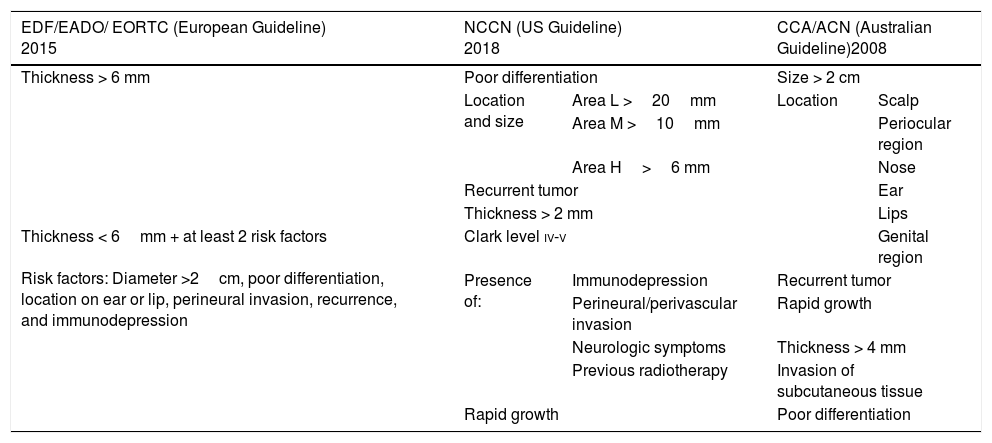

Radiotherapy in Other High-Risk cSCCsPostoperative radiotherapy has also been recommended for high-risk tumors.67 The main challenge lies in the definition of high risk. Although the main guidelines on the management of cSCC differ in some aspects (Table 2), they largely agree on the following factors defining high risk: a diameter of over 2cm, a thickness of over 2mm (and especially 6mm), poor differentiation, an ear or lip location, PNI, recurrence, and immunodepression.7,41,44,68 Nonetheless, few studies have assessed the impact or usefulness of radiotherapy in cSCC with high-risk features other than PNI, and most of the evidence that exists is from a 2009 systematic review that indicates that prognosis is generally excellent (and hence postoperative radiotherapy is not necessary) as long as the margins are negative.40 Postoperative radiotherapy has also been found to be useful in cSCCs with high-risk features other than PNI or positive surgical margins, such as cSCCs with cranial nerve invasion.69

Classification of High-Risk Squamous Cell Carcinoma According to European, US, and Australian Guidelines.

| EDF/EADO/ EORTC (European Guideline) 2015 | NCCN (US Guideline) 2018 | CCA/ACN (Australian Guideline)2008 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thickness > 6 mm | Poor differentiation | Size > 2 cm | ||

| Location and size | Area L >20mm | Location | Scalp | |

| Area M >10mm | Periocular region | |||

| Area H>6 mm | Nose | |||

| Recurrent tumor | Ear | |||

| Thickness > 2 mm | Lips | |||

| Thickness < 6mm + at least 2 risk factors Risk factors: Diameter >2cm, poor differentiation, location on ear or lip, perineural invasion, recurrence, and immunodepression | Clark level iv-v | Genital region | ||

| Presence of: | Immunodepression | Recurrent tumor | ||

| Perineural/perivascular invasion | Rapid growth | |||

| Neurologic symptoms | Thickness > 4 mm | |||

| Previous radiotherapy | Invasion of subcutaneous tissue | |||

| Rapid growth | Poor differentiation | |||

Abbreviations: CCA/ACN indicates Cancer Council Australia/Australian Cancer Network; EDF/EADO/ EORTC indicates European Dermatology Forum/European Association of Dermato-Oncology/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Area L (low risk): Trunk and extremities (excluding pretibial zone, hands, feet, nail unit, and ankle).

Area M (medium risk): Cheeks, forehead, scalp, neck, and pretibial area.

Area H (low risk): Mask areas of the face (centro-facial area, eyelids, eyebrows, periobital area, nose, lips, chin, jaw, preauricular and postauricular area, temple, ear), genitalia, hands, and feet.

Numerous authors agree that the best approach for achieving local control in cSCC with parotid gland involvement is a combination of surgery and radiotherapy.70–74

Postoperative radiotherapy has also been shown to be useful for controlling disease in patients with cSCC and cervical lymph node metastasis.71,75 In 2005, Veness et al.76 published a study evaluating 167 patients with metastatic cSCC who had been treated with surgery or with surgery and postoperative radiotherapy with curative intent.76 The patients in the combined treatment group showed lower rates of locoregional recurrence (20% vs 43%) and a higher rate of 5-year disease-free survival (73% vs 54%).76 The authors thus considered that the combination of surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy was the best option in this setting. More recent studies have showed that postoperative radiotherapy can improve prognosis77,78 and reduce the risk of death in cSCC with lymph node metastasis, which has a worse prognosis than cSCC with parotid involvement only.71,79,80 There is some consensus that postoperative radiotherapy is useful in cases of locally advanced cSCC or cSCC with parotid or lymph node metastasis, particularly in patients with extracapsular extension or multiple node involvement.20

Elective irradition of a clinically N0 neck has also been found to achieve better local control in patients with confirmed parotid involvement81,82 and vice versa, as in both cases subclinical metastasis is assumed to exist. Other authors, in turn, recommend irradiating the cervical lymph node region in patients with high-risk cSCC83 or cSCC with PNI,53 although the evidence supporting this recommendation is weaker.

Usefulness of Chemoradiotherapy in Achieving Disease Control in cSCCSystemic treatments that increase radiosensitivity (chemoradiotherapy) can significantly improve disease control compared with radiotherapy alone in locally advanced or regionally metastatic tumors.84,84 Nonetheless, several studies have demonstrated the toxicity of this combined option for cSCC, particularly in the case of regimens including the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor cetuximab.86 A recent phase III clinical trial (TROG 05.01 trial, NCT00193895) evaluated the usefulness of chemoradiotherapy (with carboplatin) versus postoperative radiotherapy only in patients with high-risk cutaneous cSCC with lymph node involvement (extracapsular nodal extension, intraparotid nodal disease, involvement of 2 or more lymph nodes or involvement of a lymph node >3cm) or high-risk primary tumors (T3-T4 or in-transit metastasis). The results showed that the addition of chemotherapy did not offer any benefit in terms of locoregional recurrence or disease-free survival.87

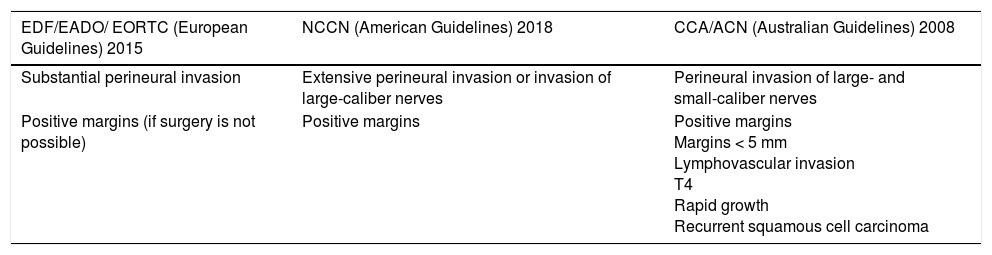

Clinical Guideline Recommendations on the Use of Radiotherapy in cSCCThere is broad consensus on the usefulness of adjuvant radiotherapy in cSCC with PNI, particularly in the case of extensive involvement or invasion of nerves with a diameter of 0.1mm or more.7,67 The European guidelines, like their US counterpart, also recommend adjuvant radiotherapy for cSCC with positive surgical margins when reintervention is not possible.7 The Australian guidelines contain the largest number of indications for adjuvant radiotherapy and even consider it a useful option for tumors with positive margins, high-risk tumors with margins measuring less than 5 mm, fast-growing tumors, T4 tumors (according to the UICC-2009 classification), and recurrent tumors67 (Table 3).

Indications for Adjuvant Radiotherapy According to European, US, and Australian Guidelines.

| EDF/EADO/ EORTC (European Guidelines) 2015 | NCCN (American Guidelines) 2018 | CCA/ACN (Australian Guidelines) 2008 |

|---|---|---|

| Substantial perineural invasion | Extensive perineural invasion or invasion of large-caliber nerves | Perineural invasion of large- and small-caliber nerves |

| Positive margins (if surgery is not possible) | Positive margins | Positive margins Margins < 5 mm Lymphovascular invasion T4 Rapid growth Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma |

Abbreviations: CCA/ACN indicates Cancer Council Australia/Australian Cancer Network; EDF/EADO/ EORTC indicates European Dermatology Forum/European Association of Dermato-Oncology/European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network.

Radiotherapy is useful for achieving disease control in cSCC. On the one hand, it provides an alternative for selected patients who cannot or choose not to undergo surgery or who have unresectable tumors. There is as yet no conclusive evidence to guide the use of postoperative radiotherapy in cSCC according to the size of involved nerves. There is, however, evidence supporting its use in cases with large-caliber nerve involvement (clinical or radiological PNI)39 or histologic (incidental) PNI involving more than 2 nerves (extensive histologic PNI).39,50,52 Postoperative radiotherapy is also useful for achieving local control in cSCC with parotid involvement71,72 and locoregional cervical lymph node metastasis.76,80 Combined parotid and cervical regional lymph node metastasis is common and elective cervical lymph node irradiation without cervical lymphadenectomy is useful for achieving local control in cSCC with confirmed parotid metastasis only.81,82,88 These indications should also be contemplated in the case of immunodepressed patients, as the benefits of radiotherapy in this setting would outweigh its contraindication in this population. There is some controversy about the usefulness of chemoradiotherapy, as some studies have shown it to be superior to postoperative radiotherapy alone,84,85,89 while others have linked its use to an increase in toxicity. Postoperative radiotherapy appears to be useful and the various clinical guidelines agree on its value for treating cSCC with positive margins that cannot be re-excised, although few studies have evaluated this indication.66 Finally, postoperative radiotherapy may be useful in certain cSCCs with high-risk features (even without PNI and with tumor-free margins after excision). There are recommendations to this effect in some guidelines, although again, studies are lacking and according to 1 systematic review, it would appear that surgery alone is not inferior to surgery and postoperative radiotherapy in patients with negative margins.40

FundingJ.C. received partial funding from the intensification INT program INT/M/16/17 of the Regional Health Office of Castilla-Leon.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cañueto J, Jaka A, Toll A. Utilidad de la radioterapia en adyuvancia en el carcinoma epidermoide cutáneo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:476–484.