Resident training in dermatology is an increasingly demanding process that has evolved over recent years. Medical-surgical dermatology and venereology is a regulated specialty in Spain pursuant to the Law of July 20, 1955 and Royal Decree (RD) 2015 of June 15, 1978.1,2 Training in this specialty lasts 4 years and is regulated by the Spanish Ministry of Health.3 Since the beginning of the MIR resident training system, the number of places and demand for them has gradually increased, and this is now the first specialty to fill all its places in the past 5 years (MIR places, 2013-2018). Furthermore, social demand for the services of dermatologists has increased for different reasons, such as the increased cosmetic needs of the population, the increase in potentially avoidable referrals from primary-care physicians, and the expansion of the fields covered by dermatology.4 To date, no study has been made of opinion regarding specialized training in dermatology at the national level.

A transversal study was carried out by means of a survey carried out in person on February 9, 2019, during the course on cosmetic dermatology for year-3 residents; the survey collected information on aspects relating to teaching, research, and general satisfaction and expectations (Appendix A).

A total of 52 residents (33 women) responded to the survey. The mean (SD) number of residents per department was 5.8 (3.0), with 2.1 (1.8) tutors per hospital and 2.6 (2.6) tutorials per year.

Each department had a mean of 4 operating theaters assigned per week with local anesthesia and 1 with general anesthesia. Of all the residents, 88.5% (46/52) had performed a flap and 75% (39/52) had performed a graft as lead surgeon on at least 1 occasion prior to the interview.

A mean (SD) of 3 (1) clinical sessions were organized per week in each department, 65.9% of which were given by residents. Only 25% (13/52) of the participants performed clinical sessions with patients. A total of 80.8% (42/52) performed sessions in collaboration with other departments with a mean (SD) frequency of 3.1 (1.5) per month. The periodicity of the research sessions was 0.6 per month.

The overall level of satisfaction with the residency was 4/5; the lowest score was achieved in training in research (2.2/5) and the highest on external rotations (4.4/5). Overall satisfaction with teaching perceived by the residents was 3.5/5 (Fig. 1).

Of those surveyed, 69.2% (36/52) felt that regular examinations were useful and 40.4% (21/52) stated that they would be prepared to undergo a final examination in the residency backed by AEDV.

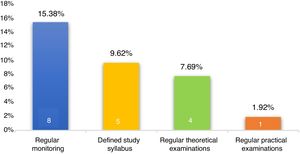

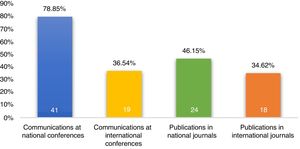

The information on teaching monitoring and communications is shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

The residents considered that patient-care tasks largely made teaching (4.2/5) and research (4.3/5) more difficult. Only 7.7% (4/52) used innovative teaching tools. A total of 71.2% (37/52) had quite a lot or a lot of availability to attend training courses. Only 11.5% (6/52) of the residents had begun their doctoral thesis.

The mean score for the difficulty in finding work was 2.5/5. In terms of employment setting, 75% of the residents wanted to work in both public and private health care, 9.6% indicated a desire to work only in public health care, and none of the residents wanted to work exclusively in private health care.

The rise of dermatology is not limited to the national level.5 In fact, the portfolio of dermatology departments has gradually increased with social demand, which implies greater dynamism in the process of teaching and learning.

Overall, the residents demand closer monitoring of their theoretical and practical training. Some consider the option of taking regular examinations as an option for evaluating their development, although debate exists on this topic, as it has been shown that current residents prefer frequent and detailed monitoring, essentially using informal rather than formal methods.6 These results would appear to agree with the learning preferences of the millennial generation—those born between 1981 and 1999,7,8 which accounts for most of the residents in training.

The scarce use of innovative teaching tools used is notable, even though social media and new technologies are on the rise. St Claire KM et al also reported low use of social media in their programs.9

Training in research is scarce. In contrast, a US study showed a growing trend in the number of publications among its aspiring dermatologists, although this was accompanied by a reduction in the number of doctorates.10 This lack of interest in writing a doctoral thesis may be explained by the low value placed on it by the current health care authorities.

In conclusion, this article shows the current vision of residents surveyed regarding their training and shows some aspects that can be improved, notably the demand for closer monitoring of theoretical and practical training and greater training in research.

Please cite this article as: Montero-Vilchez T, Molina-Leyva A, Martinez-Lopez A, Buendia-Eisman A, Ortega-Olmo R, Serrano-Ortega S, et al. Opinión sobre la formación especializada en dermatología en España. Resultados de una encuesta administrada a 53 médicos internos residentes en dermatología de tercer año en 2020. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:287–290.