Pityriasis rubra pilaris (PRP) is an inflammatory disease of unknown etiology1 with an estimated incidence ranging from 1 in 5000 to 1 in 50 000 dermatology patients. The established Griffiths classification recognizes 5 groups (types I-V) according to clinical features and patient age.2 More recently, Miralles et al.3 added a sixth group after observing clinical differences in cases associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Type I (classic adult PRP) is the most common subtype. Complete remission is achieved within 3 years of onset in 80% of cases,1 whereas recurrence occurs in 20% of cases. Systemic retinoids, specifically acitretin, are the current first-line treatment.

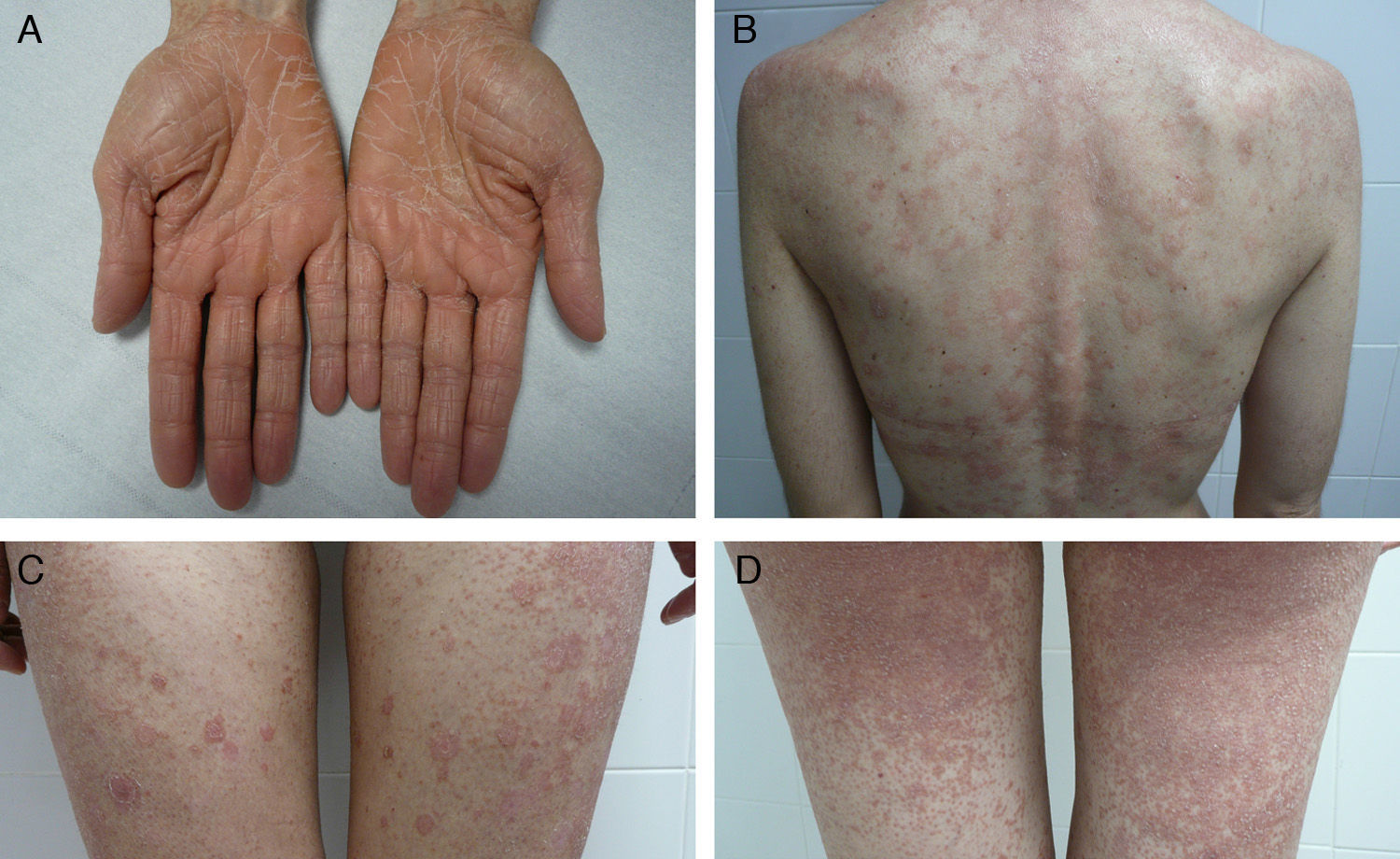

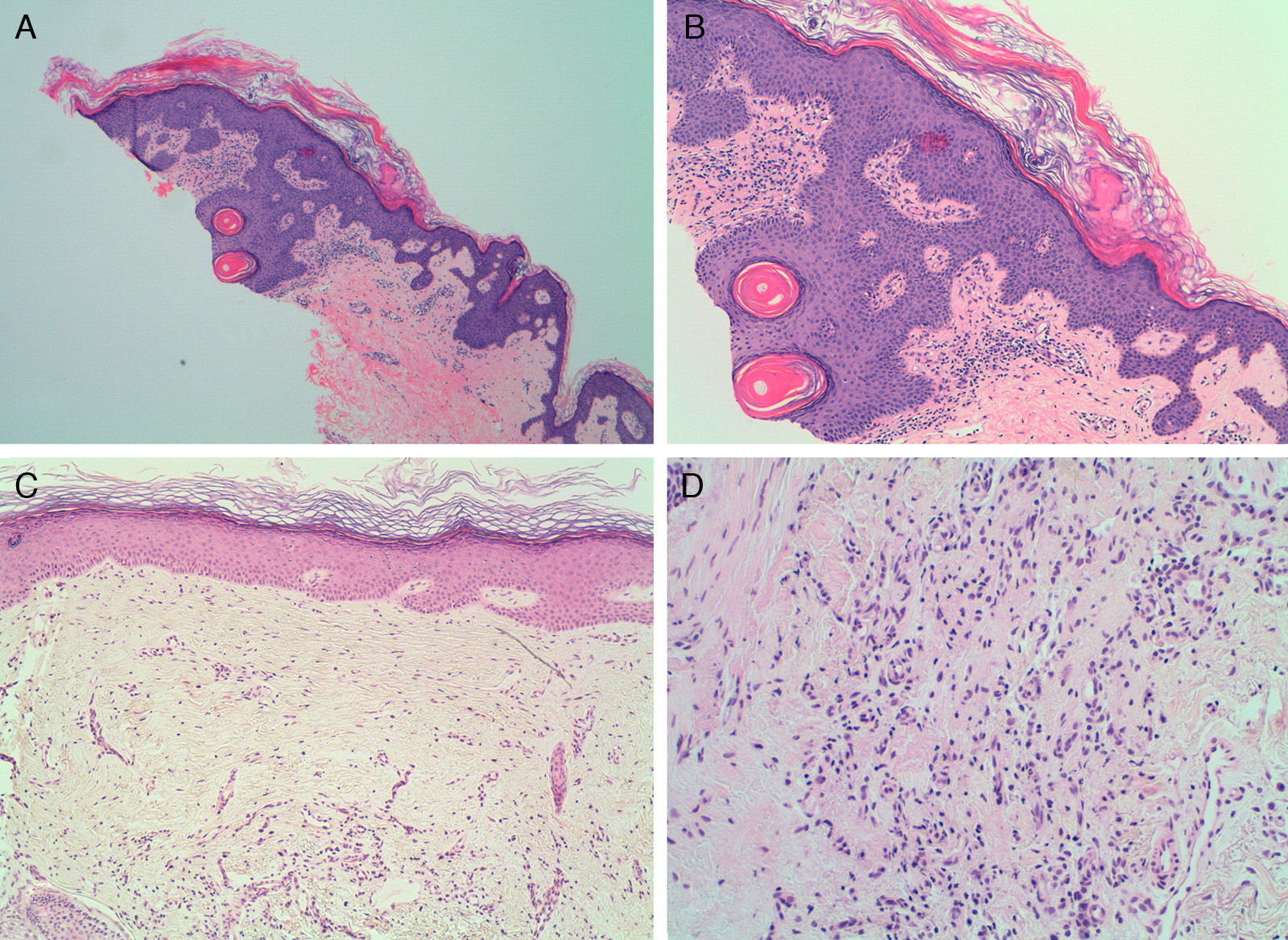

We report for the first time a case of classic adult type I PRP associated at first recurrence with rapidly developing disseminated scarring alopecia of the scalp. The patient was a 41-year-old woman with no relevant past history who presented with a pruritic rash that had appeared 3 weeks earlier at the same time as an orange-hued waxy palmoplantar keratoderma (Fig. 1, A). The trunk and the proximal extremities had orange-red lesions with some apparently healthy areas of skin (Fig. 1, B-D). Skin biopsy confirmed the suspected diagnosis of classic adult type I PRP. Findings included alternating hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis as well as psoriasiform acanthosis (Fig. 2, A and B). Treatment was started with 25 mg of oral acitretin daily. After 8 months of treatment the rash had cleared completely; we thus decided to discontinue treatment 2 months later. The patient returned after 10 lesion-free months complaining of a new crop of skin lesions similar to the original ones. This new bout occurred together with what appeared to be a severe form of scarring alopecia forming irregular patches on the scalp. The hairless patches were pearly and shiny, with fine scaling and perifollicular erythema. The clinical course was fulminant, and after 2 weeks the only scalp finding was atrophic alopecia patches with no erythema or scaling (Fig. 3). A biopsy specimen obtained from the periphery of one of the hairless patches and comprising some follicles and perifollicular erythema exhibited significant perifollicular stellate fibrosis replacing the follicles, with no signs of inflammatory infiltrate (Fig. 2, C and D). Direct immunofluorescence was negative. Blood tests showed no abnormalities; test results for antinuclear antibodies, cryoglobulins, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were all negative, and hepatitis B and C, HIV, and syphilis were ruled out. The rash cleared after 4 months of oral acitretin treatment, but the scarring alopecia persisted without change. The patient has worn a wig since then and has had no further bouts of PRP. Her scarring alopecia could not be reversed and remains stable at the time of writing in 2013, after 3 years of follow-up from initial presentation.

A and B, Skin biopsy of a pityriasis rubra pilaris lesion showing hyperkeratosis alternating with parakeratosis. A, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×4. B, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×10. C and D, Scalp biopsy with stellate perifollicular dermal fibrosis. No perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate is seen. C, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×10. D, Hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×20.

The onset of scarring alopecia of the scalp in conjunction with a second bout of type I PRP suggested to us that alopecia might have been induced by the follicular involvement characteristic of PRP.

Although fine scaling of the scalp and face is frequent in type I PRP,2 and is sometimes accompanied by nonscarring alopecia,4 an association of type I PRP with scarring alopecia has not been described before. In 1968, Bergeron and Stone5 reported the case of a patient with PRP who developed acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa, and dissecting cellulitis of the scalp. Acitretin-induced scarring alopecia has never before been reported,6 and in any case, our patient was no longer taking acitretin at the onset of the second bout and of scarring alopecia. The follicular hyperkeratosis and perifollicular erythema of the scalp present during both bouts of type I PRP could have disturbed our patient's hair follicles enough to trigger fulminant scarring alopecia.

The clinical appearance of our patient's scarring alopecia is reminiscent of pseudopelade of Brocq in large, scattered patches. It is unclear whether pseudopelade is a disease in itself or the final stage of other, primary forms of scarring alopecia. In the initial stage, our patient's condition resembled lichen planopilaris or cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Nevertheless, the absence of any perifollicular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate, the replacement of hair follicles with dermal fibrosis, and the negative direct immunofluorescence test results make lichen, lupus, and pseudopelade unlikely diagnoses.

We therefore consider this to be a case of scarring alopecia of an unusually fulminant course and severity associated with a bout of type I PRP, and with histologic findings that rule out a primary classic form of scarring alopecia. The alopecia underwent rapid clinical transformation into generalized pseudopelade in large patches, but the only histologic finding was fibrosis.

Please cite this article as: Martín Callizo C. Alopecia cicatricial en pitiriasis rubra pilaris tipo I clásica del adulto. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:955–957.