This article, part of a the series on safety in dermatologic procedures, covers the diagnosis, prevention, management, and treatment of 3 situations or conditions. The first condition we address is anaphylaxis, an uncommon but severe and potentially fatal reaction that must be recognized quickly so that urgent management coordinated with an anesthesiologist can commence. The second is fainting due to a vasovagal reaction, which is the most common complication in dermatologic surgery. This event, which occurs in 1 out of every 160 procedures, usually follows a benign course and resolves on its own. However, in patients susceptible to vasovagal reactions, syncope may lead to asystole and cardiac arrest. The third is acute hyperventilation syndrome, which is an anomalous anxiety-related increase in breathing rate beyond metabolic requirements. Brief practical recommendations for managing all 3 events are included.

En el presente artículo de la serie “Seguridad en procedimientos dermatológicos” se aborda el diagnóstico, prevención, manejo y tratamiento de tres situaciones. Primeramente, se aborda la anafilaxia: una situación infrecuente, grave y potencialmente mortal, que requiere una identificación ágil para un manejo urgente coordinado por parte de médicos especialistas en Anestesiología. En segundo lugar, la reacción vasovagal, que es la complicación médica más frecuente durante la cirugía dermatológica (1 de cada 160 intervenciones), con una evolución habitualmente benigna autorresolutiva, pero que en individuos muy sensibles puede provocar una parada cardiaca por asistolia. En tercer y último lugar, el síndrome de hiperventilación aguda, que es una respuesta anómala de determinados individuos a un evento estresante, con un incremento de la ventilación que excede la demanda metabólica. En los tres casos se incluyen recomendaciones que se plasman de forma práctica y somera.

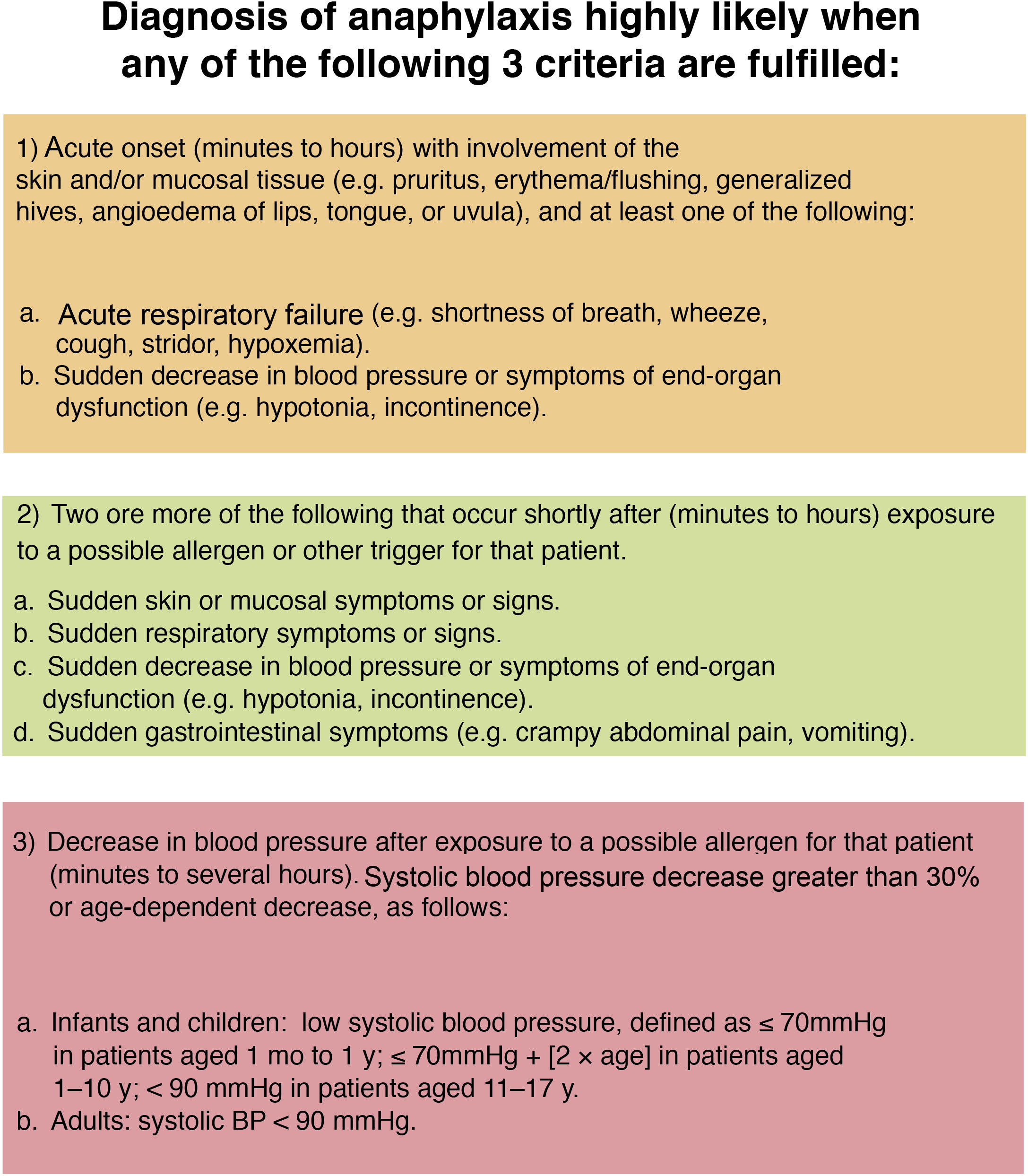

Anaphylaxis is a severe, life-threatening situation, albeit rare. It can be caused by immunoglobulin E (IgE)-dependent or IgE-independent mechanisms. The characteristic clinical signs are presented in Figure 1.1 Recurrent skin and mucosal manifestations may or may not be observed, and clinical signs may be limited to arrhythmias, acute coronary syndrome, or severe asthma.

Clinical manifestations of suspected anaphylaxis.

Adapted from Shaker et al.1

Risk factors for poor outcome include chronic respiratory diseases, certain medications (β-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and benzodiazepines), a personal history of mastocytosis, and delayed adrenaline administration.1,2

Avoidance of triggers is essential for prevention. This means that the patient’s known allergies must be taken into account (e.g. latex allergies and possible cross-reactivity with foods such as kiwi, avocado, or banana).1,2

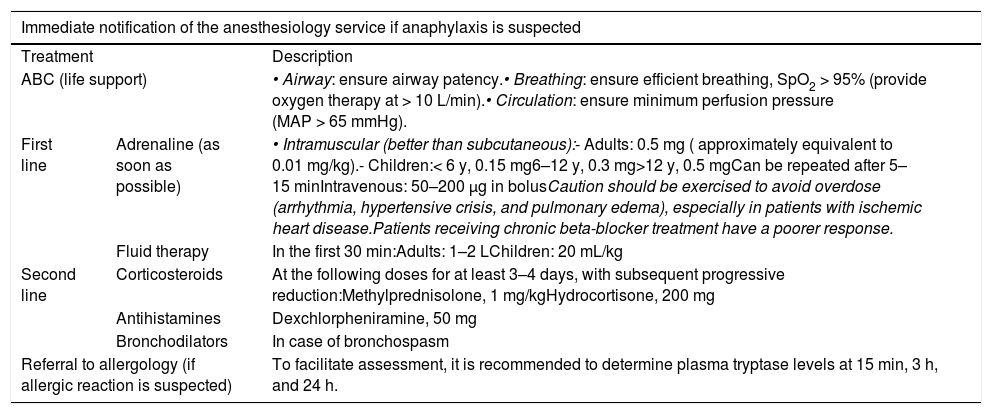

When considering treatment2 (Table 1) it is important to bear the following points in mind:

- 1)

The anesthesiology or intensive care services should be alerted as soon as anaphylaxis is suspected.

- 2)

Adrenaline should be administered early.

- 3)

The causative agent (e.g. antibiotics, blood products, contrast medium, latex) must be removed.

- 4)

The risk of biphasic responses (e.g. symptom recurrence without re-exposure to the causative agent) in the first 24–72 hours, which require hospital admission in severe cases, must be considered.

Treatment of Anaphylaxis

| Immediate notification of the anesthesiology service if anaphylaxis is suspected | ||

|---|---|---|

| Treatment | Description | |

| ABC (life support) | • Airway: ensure airway patency.• Breathing: ensure efficient breathing, SpO2 > 95% (provide oxygen therapy at > 10 L/min).• Circulation: ensure minimum perfusion pressure (MAP > 65 mmHg). | |

| First line | Adrenaline (as soon as possible) | • Intramuscular (better than subcutaneous):- Adults: 0.5 mg ( approximately equivalent to 0.01 mg/kg).- Children:< 6 y, 0.15 mg6–12 y, 0.3 mg>12 y, 0.5 mgCan be repeated after 5–15 minIntravenous: 50–200 µg in bolusCaution should be exercised to avoid overdose (arrhythmia, hypertensive crisis, and pulmonary edema), especially in patients with ischemic heart disease.Patients receiving chronic beta-blocker treatment have a poorer response. |

| Fluid therapy | In the first 30 min:Adults: 1–2 LChildren: 20 mL/kg | |

| Second line | Corticosteroids | At the following doses for at least 3–4 days, with subsequent progressive reduction:Methylprednisolone, 1 mg/kgHydrocortisone, 200 mg |

| Antihistamines | Dexchlorpheniramine, 50 mg | |

| Bronchodilators | In case of bronchospasm | |

| Referral to allergology (if allergic reaction is suspected) | To facilitate assessment, it is recommended to determine plasma tryptase levels at 15 min, 3 h, and 24 h. | |

Abbreviations: MAP, mean arterial pressure; SpO2, oxygen saturation.

This is the most frequent medical complication during dermatological surgery. It has been reported in 1 in every 160 interventions.3 Although its presentation may be alarming, it usually has a benign, self-resolving course. However, in very sensitive individuals it can cause cardiac arrest due to asystole.4

It is caused by a pathological response to various stimuli of the autonomic reflexes that control blood pressure and heart rate. The Bezold-Jarisch reflex is activated, causing an initial loss of sympathetic tone (hypotension) followed by intense vagal discharge (bradycardia). Either of the two components can predominate. The resulting cerebral hypoperfusion can cause a temporary loss of consciousness (syncope).

Although this type of reaction can occur in any individual in certain circumstances, predisposing factors include individual susceptibility (a history of vagal reactions to previous invasive procedures), age less than 35 years, female sex, lack of sleep, fasting, ambient heat, and standing.4

In dermatological surgery, triggers include fear, the sight of blood and needles, and pain.

Due to its neurogenic mechanism, onset occurs rapidly (within seconds) and the episode duration can range from seconds to minutes. With patient monitoring, a drop in blood pressure and heart rate can be detected before the patient experiences symptoms, which include feelings of weakness and dizziness, paleness, sweating, and occasionally nausea and vomiting. If the reaction proceeds loss of consciousness may occur, followed by brief tonic–clonic contractions if the cerebral ischemia is very abrupt.

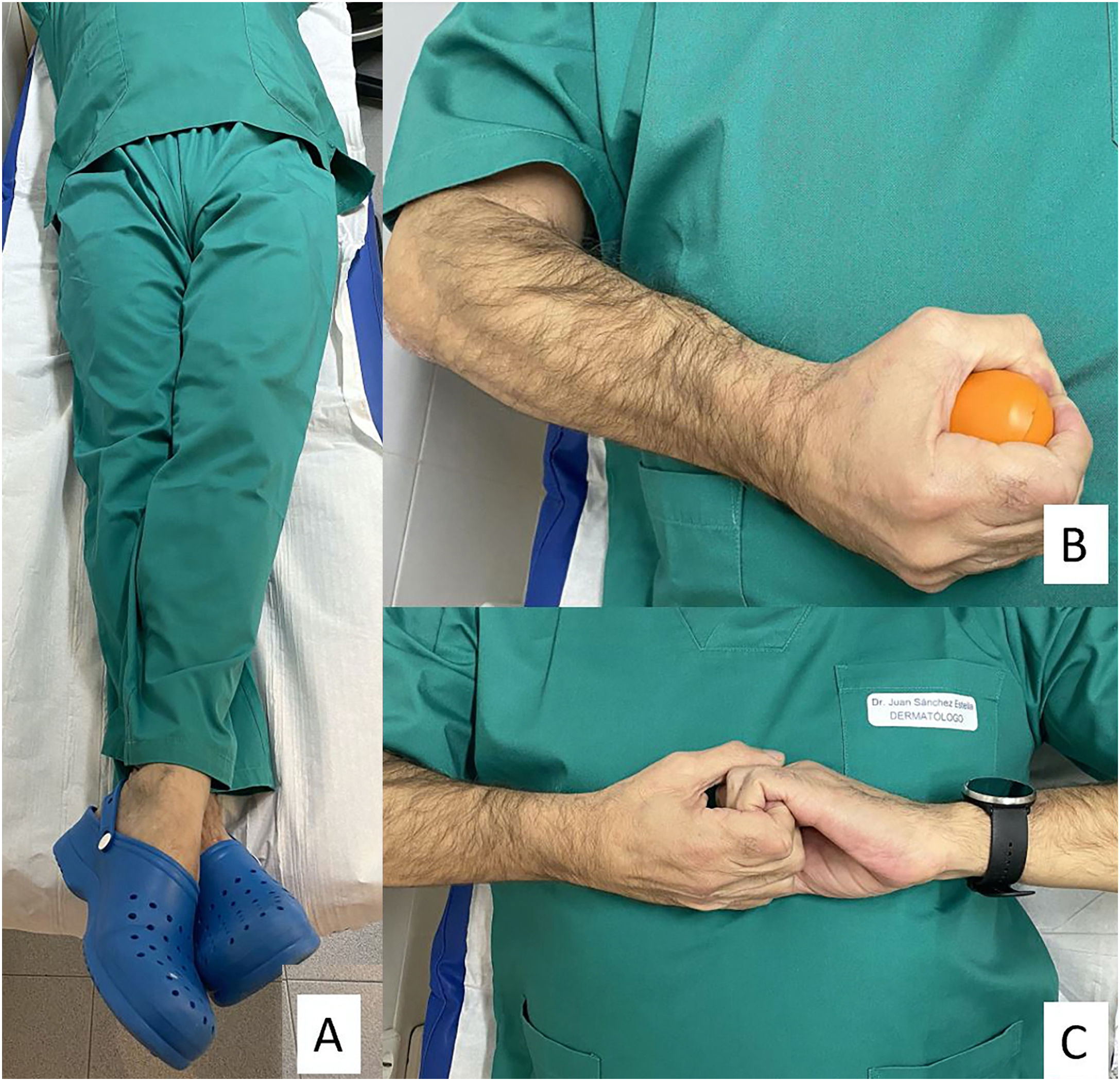

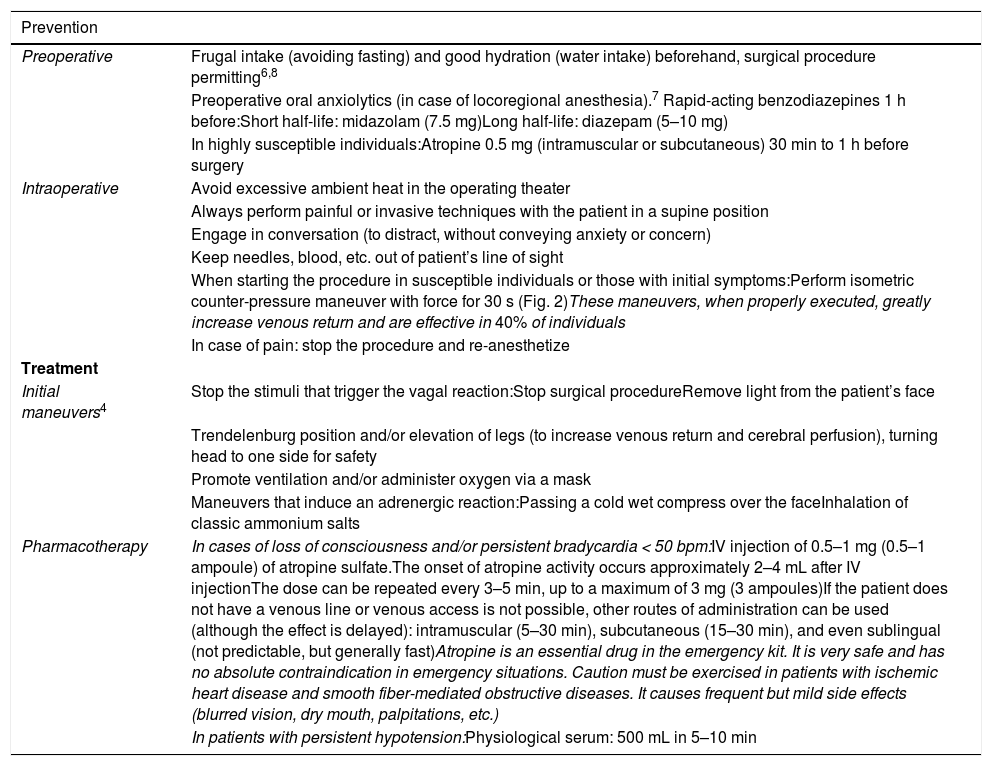

Preventive measures should be applied in young patients and/or those with a history of reactions of this type. Preventive measures and treatment, to be applied after onset, are listed in Table 2.

Prevention and Treatment of Vasovagal Reaction4,6–8

| Prevention | |

|---|---|

| Preoperative | Frugal intake (avoiding fasting) and good hydration (water intake) beforehand, surgical procedure permitting6,8 |

| Preoperative oral anxiolytics (in case of locoregional anesthesia).7 Rapid-acting benzodiazepines 1 h before:Short half-life: midazolam (7.5 mg)Long half-life: diazepam (5–10 mg) | |

| In highly susceptible individuals:Atropine 0.5 mg (intramuscular or subcutaneous) 30 min to 1 h before surgery | |

| Intraoperative | Avoid excessive ambient heat in the operating theater |

| Always perform painful or invasive techniques with the patient in a supine position | |

| Engage in conversation (to distract, without conveying anxiety or concern) | |

| Keep needles, blood, etc. out of patient’s line of sight | |

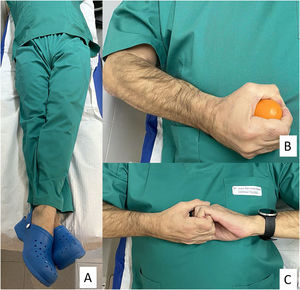

| When starting the procedure in susceptible individuals or those with initial symptoms:Perform isometric counter-pressure maneuver with force for 30 s (Fig. 2)These maneuvers, when properly executed, greatly increase venous return and are effective in 40% of individuals | |

| In case of pain: stop the procedure and re-anesthetize | |

| Treatment | |

| Initial maneuvers4 | Stop the stimuli that trigger the vagal reaction:Stop surgical procedureRemove light from the patient’s face |

| Trendelenburg position and/or elevation of legs (to increase venous return and cerebral perfusion), turning head to one side for safety | |

| Promote ventilation and/or administer oxygen via a mask | |

| Maneuvers that induce an adrenergic reaction:Passing a cold wet compress over the faceInhalation of classic ammonium salts | |

| Pharmacotherapy | In cases of loss of consciousness and/or persistent bradycardia < 50 bpm:IV injection of 0.5–1 mg (0.5–1 ampoule) of atropine sulfate.The onset of atropine activity occurs approximately 2–4 mL after IV injectionThe dose can be repeated every 3–5 min, up to a maximum of 3 mg (3 ampoules)If the patient does not have a venous line or venous access is not possible, other routes of administration can be used (although the effect is delayed): intramuscular (5–30 min), subcutaneous (15–30 min), and even sublingual (not predictable, but generally fast)Atropine is an essential drug in the emergency kit. It is very safe and has no absolute contraindication in emergency situations. Caution must be exercised in patients with ischemic heart disease and smooth fiber-mediated obstructive diseases. It causes frequent but mild side effects (blurred vision, dry mouth, palpitations, etc.) |

| In patients with persistent hypotension:Physiological serum: 500 mL in 5–10 min |

Abbreviation: IV, intravenous.

Acute hyperventilation syndrome is an abnormal response in certain individuals to a stressful event, characterized by an increase in ventilation that exceeds metabolic demand. It is more frequent in individuals with anxiety, who, in situations of fear, breathe rapidly and shallowly using the upper part of the thorax. This breathing pattern is often not apparent. This leads to a decrease in the partial pressure of CO2 in the blood, which is the main regulator of cerebral circulation, giving rise to the cerebral vasoconstriction that underlies the clinical signs.

It is characterized, initially, by a dysphoric presentation, including anxiety, lightheadedness, shortness of breath and upset stomach, nausea, belching, chest tightness, perioral numbness, acral paresthesia, and even tetany of the hands. Blood pressure and heart rate are initially normal, but syncope can occur if the episode progresses.

Up until several years ago breathing into a paper bag was recommended in cases of hyperventilation with no organic cause. However, this technique is no longer considered effective. Current treatment consists of guiding the patient’s breathing, applying pressure with one hand on the upper chest, and encouraging the patient to breathe more slowly using the diaphragm (abdominal breathing).5

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank all speakers and participants in the series of conferences on safety in dermatological procedures, as well as all members of the Dermachat dermatological forum.

Several weeks after submitting this article Dr. Sánchez-Estella died of COVID-19. He will be remembered with the deepest gratitude and admiration.