Actinic keratoses (AKs) are common cutaneous lesions that develop as a result of ultraviolet (UV) radiation damage.1 Risk factors associated with AKs include advanced age, male gender, high degree of sun and/or artificial UV exposure, and fair skin.2 Epidemiological studies within Europe are limited and have provided highly variable estimates of AK point prevalence (1–38%).2–6 Cumulative sun exposure, demographic AK risk factors, and lifestyle characteristics have likely contributed to the wide-ranging estimate of European AK prevalence.7,8

Comprehensive studies that measure nationwide AK prevalence within Europe would provide essential information that would aid the development of pragmatic AK management guidelines. The aim of the EPIQA study was to assess the prevalence of AKs among dermatology outpatient clinics in Spain.9 In this analysis, we report the secondary objective of describing dermatology outpatient clinic AK prevalence within four regions of Spain with different climate conditions.

The EPIQA study was an observational, cross-sectional, multicentre study that included patients attending general dermatology outpatient clinics in Spain.9 In order to represent the entire country, clinics were selected and divided into four geographical regions based on climatic conditions and lifestyle: Northern (Galicia, Asturias,Navarra and Aragón), Central (Castilla-León, Madrid, and Castilla-La-Mancha), Mediterranean (Cataluña, Comunidad Valenciana and Murcia) and Southern (Extremadura and Andalucía) regions. Whole-body examinations were performed by certified dermatologists who visually confirmed AKs. Medical history, profession, and sun/UV exposure habits were collected via standardised interviews. Statistical analysis have been previously described.9

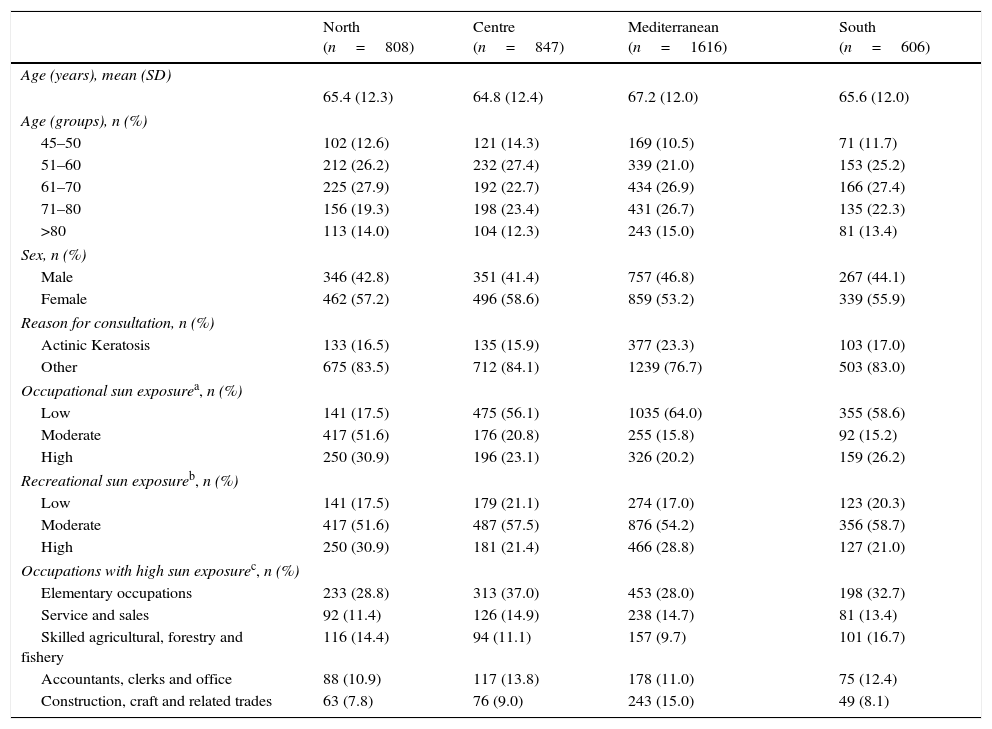

A total of 3877 patients were included with characteristics shown in Table 1. Overall, age and sex were similar between regions. Age distributions were also similar between regions, with ages 45–50 representing 11.9% and >80 years old representing 14.0% of the population. Actinic keratosis being the reason for the dermatology consultation varied from 15.9% to 23.3%. Most patients reported low occupational but moderate recreational sun exposure.

Sociodemographic data.

| North (n=808) | Centre (n=847) | Mediterranean (n=1616) | South (n=606) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | ||||

| 65.4 (12.3) | 64.8 (12.4) | 67.2 (12.0) | 65.6 (12.0) | |

| Age (groups), n (%) | ||||

| 45–50 | 102 (12.6) | 121 (14.3) | 169 (10.5) | 71 (11.7) |

| 51–60 | 212 (26.2) | 232 (27.4) | 339 (21.0) | 153 (25.2) |

| 61–70 | 225 (27.9) | 192 (22.7) | 434 (26.9) | 166 (27.4) |

| 71–80 | 156 (19.3) | 198 (23.4) | 431 (26.7) | 135 (22.3) |

| >80 | 113 (14.0) | 104 (12.3) | 243 (15.0) | 81 (13.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 346 (42.8) | 351 (41.4) | 757 (46.8) | 267 (44.1) |

| Female | 462 (57.2) | 496 (58.6) | 859 (53.2) | 339 (55.9) |

| Reason for consultation, n (%) | ||||

| Actinic Keratosis | 133 (16.5) | 135 (15.9) | 377 (23.3) | 103 (17.0) |

| Other | 675 (83.5) | 712 (84.1) | 1239 (76.7) | 503 (83.0) |

| Occupational sun exposurea, n (%) | ||||

| Low | 141 (17.5) | 475 (56.1) | 1035 (64.0) | 355 (58.6) |

| Moderate | 417 (51.6) | 176 (20.8) | 255 (15.8) | 92 (15.2) |

| High | 250 (30.9) | 196 (23.1) | 326 (20.2) | 159 (26.2) |

| Recreational sun exposureb, n (%) | ||||

| Low | 141 (17.5) | 179 (21.1) | 274 (17.0) | 123 (20.3) |

| Moderate | 417 (51.6) | 487 (57.5) | 876 (54.2) | 356 (58.7) |

| High | 250 (30.9) | 181 (21.4) | 466 (28.8) | 127 (21.0) |

| Occupations with high sun exposurec, n (%) | ||||

| Elementary occupations | 233 (28.8) | 313 (37.0) | 453 (28.0) | 198 (32.7) |

| Service and sales | 92 (11.4) | 126 (14.9) | 238 (14.7) | 81 (13.4) |

| Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery | 116 (14.4) | 94 (11.1) | 157 (9.7) | 101 (16.7) |

| Accountants, clerks and office | 88 (10.9) | 117 (13.8) | 178 (11.0) | 75 (12.4) |

| Construction, craft and related trades | 63 (7.8) | 76 (9.0) | 243 (15.0) | 49 (8.1) |

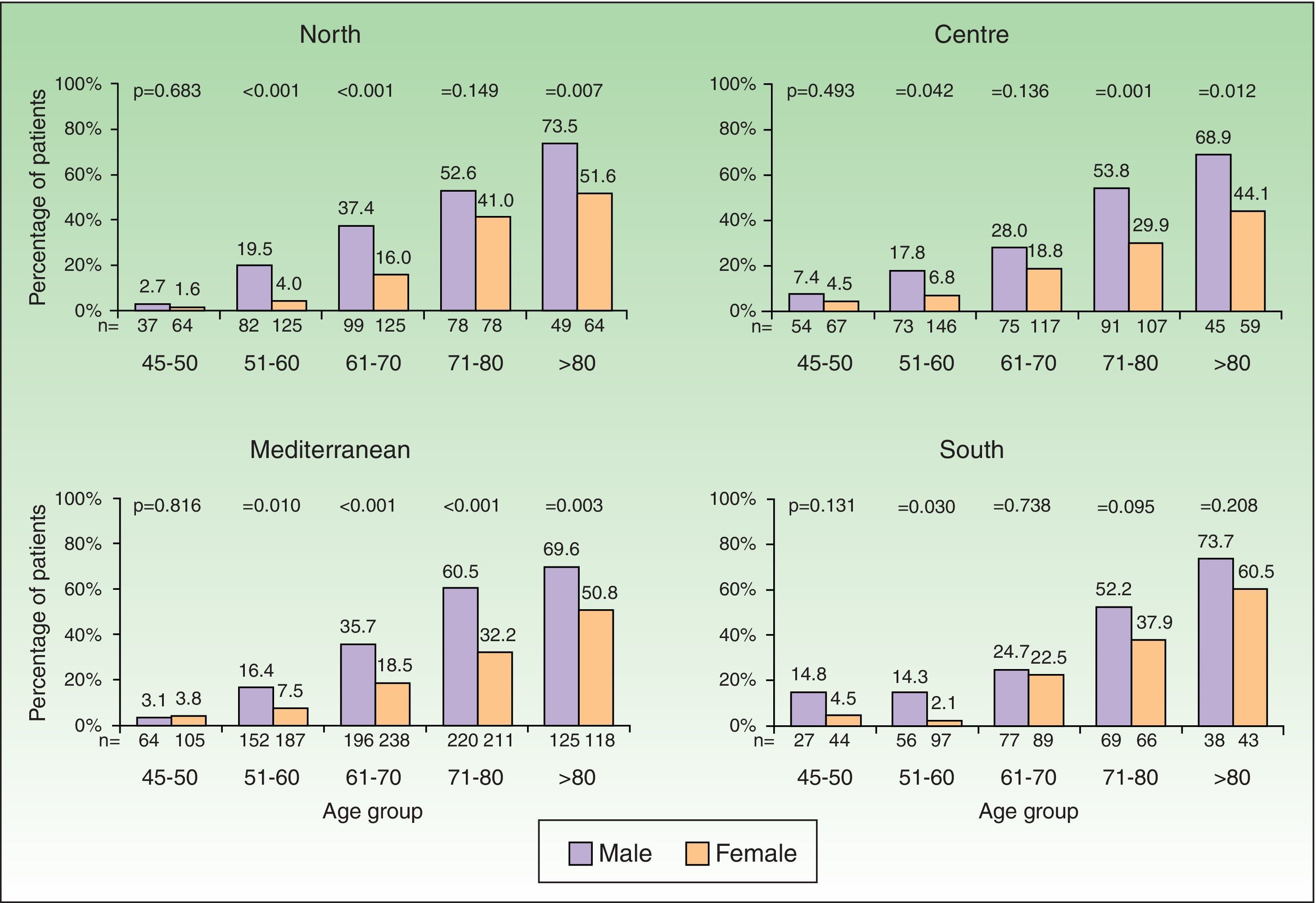

In the study population, 1110 presented with AKs (28.6%, 95% CI: 27.2, 30.1). AK point prevalence (95% CI) differed significantly between regions, with 31.4% (29.1, 33.7) in the Mediterranean, 28.1% (24.5, 31.7) in the South, 27.5% (24.4, 30.6) in the North and 24.9% (22.0, 27.8) in the Central region (p=0.006). The most significant difference in prevalence was observed between Central and Mediterranean regions (p<0.05). Communities with the highest AK point prevalence were located in the Northern (Aragón, 39.6%), Mediterranean (Cataluña, 40.1%), and Southern (Extremadura, 36.6%) regions. Point prevalence was highest in men aged ≥51 years old (p<0.001) (Fig. 1).

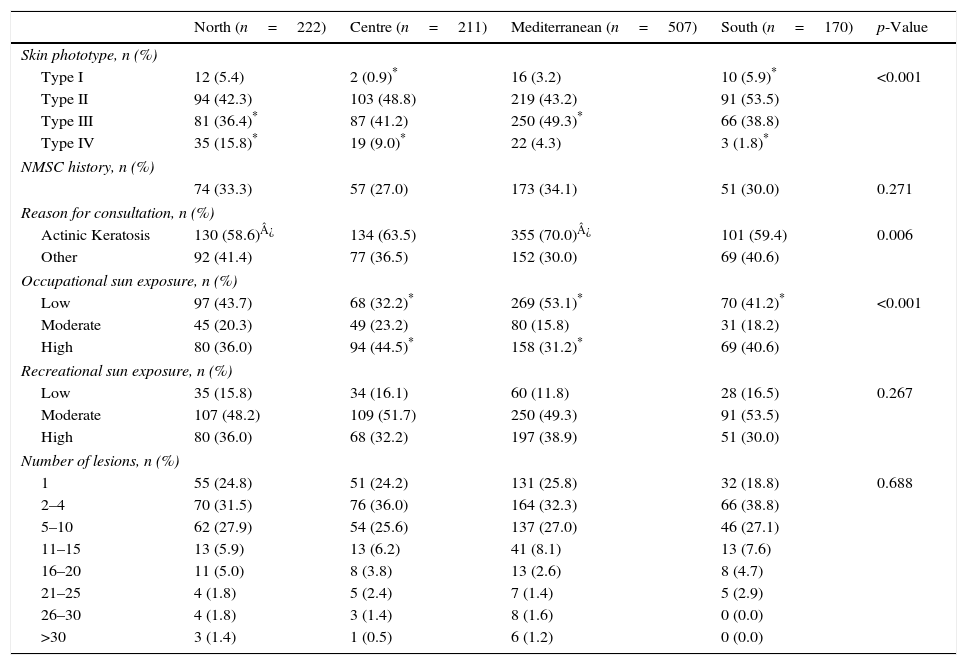

A comparison of patients diagnosed with AK found a significant difference between regional skin phototypes and no difference between regional history of non-melanoma skin cancer (Table 2). In all regions, the most prevalent phototypes were types II and III, which cumulatively accounted for 80–90% of all AK patients. A significantly higher proportion of AK patients in all regions reported that AKs were the reason for consultation, compared to other reasons (p=0.006). Significant regional differences were observed when related to occupational (p<0.001), but not to recreational (p=0.267), sun exposure (Table 2).

Lifestyle and clinical characteristics of AK patients.

| North (n=222) | Centre (n=211) | Mediterranean (n=507) | South (n=170) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin phototype, n (%) | |||||

| Type I | 12 (5.4) | 2 (0.9)* | 16 (3.2) | 10 (5.9)* | <0.001 |

| Type II | 94 (42.3) | 103 (48.8) | 219 (43.2) | 91 (53.5) | |

| Type III | 81 (36.4)* | 87 (41.2) | 250 (49.3)* | 66 (38.8) | |

| Type IV | 35 (15.8)* | 19 (9.0)* | 22 (4.3) | 3 (1.8)* | |

| NMSC history, n (%) | |||||

| 74 (33.3) | 57 (27.0) | 173 (34.1) | 51 (30.0) | 0.271 | |

| Reason for consultation, n (%) | |||||

| Actinic Keratosis | 130 (58.6)¿ | 134 (63.5) | 355 (70.0)¿ | 101 (59.4) | 0.006 |

| Other | 92 (41.4) | 77 (36.5) | 152 (30.0) | 69 (40.6) | |

| Occupational sun exposure, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 97 (43.7) | 68 (32.2)* | 269 (53.1)* | 70 (41.2)* | <0.001 |

| Moderate | 45 (20.3) | 49 (23.2) | 80 (15.8) | 31 (18.2) | |

| High | 80 (36.0) | 94 (44.5)* | 158 (31.2)* | 69 (40.6) | |

| Recreational sun exposure, n (%) | |||||

| Low | 35 (15.8) | 34 (16.1) | 60 (11.8) | 28 (16.5) | 0.267 |

| Moderate | 107 (48.2) | 109 (51.7) | 250 (49.3) | 91 (53.5) | |

| High | 80 (36.0) | 68 (32.2) | 197 (38.9) | 51 (30.0) | |

| Number of lesions, n (%) | |||||

| 1 | 55 (24.8) | 51 (24.2) | 131 (25.8) | 32 (18.8) | 0.688 |

| 2–4 | 70 (31.5) | 76 (36.0) | 164 (32.3) | 66 (38.8) | |

| 5–10 | 62 (27.9) | 54 (25.6) | 137 (27.0) | 46 (27.1) | |

| 11–15 | 13 (5.9) | 13 (6.2) | 41 (8.1) | 13 (7.6) | |

| 16–20 | 11 (5.0) | 8 (3.8) | 13 (2.6) | 8 (4.7) | |

| 21–25 | 4 (1.8) | 5 (2.4) | 7 (1.4) | 5 (2.9) | |

| 26–30 | 4 (1.8) | 3 (1.4) | 8 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| >30 | 3 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

The distribution of anatomical areas with AK lesions was similar between regions and, in general, significantly more frequently reported on the face for women and the scalp and ears for men (Supplementary Table 1). A comparison of the number of lesions by location showed no regional differences (Supplementary Table 2).

Overall, there were observed regional differences in skin phototype, the reason for consultation, and occupational sun exposure. While skin phototype and occupational sun exposure were anticipated to differ due to regional demographic and employment variability, significant differences in the percentage of patients seeking a consultation for AK suggests differing regional attitudes towards seeking healthcare services or healthcare availability. Furthermore, as 30–42% of patients with AKs ignored these lesions, it is clear that AK remains an underdiagnosed condition within Spain.

In agreement with previous results, lesion location was consistent between regions; more frequent on the scalp and ears for men, and the face for women.10 Furthermore, despite regional variation in AK risk factor frequency, no significant differences in the number of lesions were observed.

Some limitations of this study include the unequal recruitment from each autonomous community that may have imbalanced regional comparisons and the restriction of the study population to patients visiting dermatology clinics. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that has investigated regional variation of AK prevalence within a single European country.

In summary, significant regional differences in AK prevalence have been observed in Spain; predominantly related to sex and age. Regional differences in skin phototype and occupational sun exposure do not appear to influence lesion location or severity. It is striking that despite regional differences, a high proportion of patients in Spain did not seek advice regarding their AKs. These findings highlight that regional variation in AK prevalence exists and are of value to national AK screening and management initiatives.

Conflict of interestC. Ferrándiz-Pulido received speakers’ honoraria and/or consultation fees from Almirall, Leo Pharma and Isdin. C. Ferrándiz received speakers’ honoraria and/or consultation fees from Almirall, Leo Pharma and Spherium Biomed. M.J. Plazas was an employee of Almirall at the time of the study. All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank to all the investigators of the EPIQA study group (in alphabetical order): Albares Tendero MP, Alcántara Reifs CM, Alfaro Rubio A, Alonso San Pablo MT, Bassas Freixas P, Blanco Barrios S, Blanes Martínez MM, Botella Estrada R, Brufau Redondo C, Castellanos González M, Curto Barredo L, De La Corte Sánchez IS, De La Cueva Dobao P, Del Prado Sanz ME, Eiris Salvado N, El-Khalili Murjan BA, Escutia Muñoz B, Fernández López E, Ferrándiz Foraster C, Ferrándiz-Pulido L, Ferrándiz-Pulido C, Figueroa Silva O, Fuente González MJ, Galiano Mejías S, García Acebes CR, García Martínez FJ, García Rodiño S, García-Melgares Linares ML, García-Patos V, Gilaberte Calzada Y, Gómez Bernal SM, Gómez López A, Gómez Sanchez ME, Gonzalez De Arriba M, Heras Mendaza F, Hernández-Gil Bordallo A, Hernández-Gil Sánchez J, Hilari Carbonell H, Hueso Gabriel L, Lera Imbuluzqueta JM, López Aventín D, Marín Corbalán N, Martorell Calatayud A, Mateo Suárez S, Navarro Mira M, Ojeda Vila, T Pérez Caballero JA, Pérez García LJ, Pujol R, Ramírez Andreo A, Ramón Sapena R, Redondo Bellón P, Rodríguez Martín AM, Román Curto C, Romo Melgar A, Roncero Riesco M, Ruiz De Casas A, Ruiz Martínez MD, Salas García T, Salido Vallejo R, Sánchez Aguilar MD, Santos Duran JC, Segurado Rodríguez MA, Soria Martínez C, Valdés Pineda FJ, Vargas Díez E, Vázques Veigas HA, Vázquez Osorio I, Vizán de Uña MC, Yuste Chaves M.

The authors would also like to thank Xavier Cortes Gil for assistance in developing this article. Writing support was provided by Jonathan Mackinnon, PhD from TFS Develop with financial support provided by Almirall S.A. The study was sponsored and financially supported by Almirall S.A.