Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a chronic idiopathic granulomatous disease considered to occur in association with diabetes mellitus. Data on the frequency of this association, however, are inconsistent. Our aim was to retrospectively analyze the clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with NL at our hospital and to investigate the association with diabetes mellitus and other diseases.

Material and methodsWe performed a chart review of all patients with a clinical and histologic diagnosis of NL treated and followed in the dermatology department of Hospital de Bellvitge in Barcelona, Spain between 1987 and 2013.

ResultsThirty-five patients (6 men and 29 women with a mean age of 47.20 years) were diagnosed with NL in the study period. At the time of diagnosis, 31 patients had pretibial lesions. Thirteen patients (37%) had a single lesion at diagnosis, and the mean number of lesions was 3.37. Twenty-three patients (65.71%) had diabetes mellitus (type 1 in 10 cases and type 2 in 13). In 20 patients, onset of diabetes preceded that of NL by a mean of 135.70 months. The 2 conditions were diagnosed simultaneously in 3 patients. None of the 35 patients developed diabetes mellitus during follow-up. Six patients had hypothyroidism, and 4 of these also had type 1 diabetes.

ConclusionsNL is frequently associated with type 1 and 2 diabetes. Although diabetes tends to develop before NL, it can occur simultaneously.

La necrobiosis lipoídica (NL) es una enfermedad granulomatosa idiopática de curso crónico que se considera asociada a la diabetes mellitus (DM). Sin embargo, existen resultados contradictorios respecto a la frecuencia de esta asociación. Nuestro objetivo fue analizar retrospectivamente las características clínicas de nuestros pacientes con NL y su relación con la DM y otras enfermedades.

Material y métodosTodos los pacientes diagnosticados clínica e histológicamente de NL que han sido tratados y controlados en el Servicio de Dermatología del Hospital de Bellvitge de Barcelona fueron incluidos en el estudio.

ResultadosTreinta y cinco pacientes fueron diagnosticados de NL entre 1987 y 2013 (6 varones y 29 mujeres, edad media 47,20 años). En el momento del diagnóstico de la NL 31 pacientes presentaban lesiones a nivel pretibial. Trece pacientes (37%) presentaban una única lesión al ser diagnosticados y el número medio de lesiones fue de 3,37. La NL se asoció a DM en 23 pacientes (65,71%) (10 tipo 1, 13 tipo 2). En 20 casos la DM precedió al inicio de las lesiones de NL con un tiempo medio de 135,70 meses. En 3 casos la DM y la NL se diagnosticaron simultáneamente. Ninguno de nuestros pacientes con NL desarrolló DM durante el tiempo de seguimiento. Seis pacientes tenían hipotiroidismo, 4 de los cuales tenían también DM tipo 1.

ConclusionesLa NL está frecuentemente asociada a DM, tanto tipo 1 como tipo 2, y aunque esta suele precederla en años, en algún caso la aparición es simultánea.

Necrobiosis lipoidica (NL) is a chronic idiopathic granulomatous disease characterized by collagen degeneration, formation of palisading granulomas, and thickening of vessel walls.1,2 It is commonly associated with diabetes mellitus (DM). However, few studies have analyzed this association, and the results of those that have are inconsistent.1–6 Our objective was to analyze the clinical characteristics of patients with NL treated at our center and to investigate the association with DM and other diseases.

Material and MethodsThe study population comprised all patients with a clinical and histologic diagnosis of NL who were treated and followed in the Dermatology Department of Hospital Bellvitge, Barcelona, Spain between 1987 and 2013. Our institution is a tertiary-level teaching hospital that provides care to approximately 1 million people. We reviewed each patient's clinical history and collected the following data: age; sex; date of diagnosis; time between onset of lesions and diagnosis; location; number of lesions and maximum diameter at diagnosis; ulceration; presence of DM and time between onset of DM and diagnosis; association with granuloma annulare; possible association with other systemic diseases; duration of activity of NL; and length of follow-up. Data were entered into a database and analyzed using SPSS version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc) to detect possible associations. Once the distribution of data was shown to be normal, continuous variables were analyzed using the t test, and qualitative variables were analyzed using contingency tables (chi-square test and Fisher exact test). Nonparametric tests were used if data were not normally distributed.

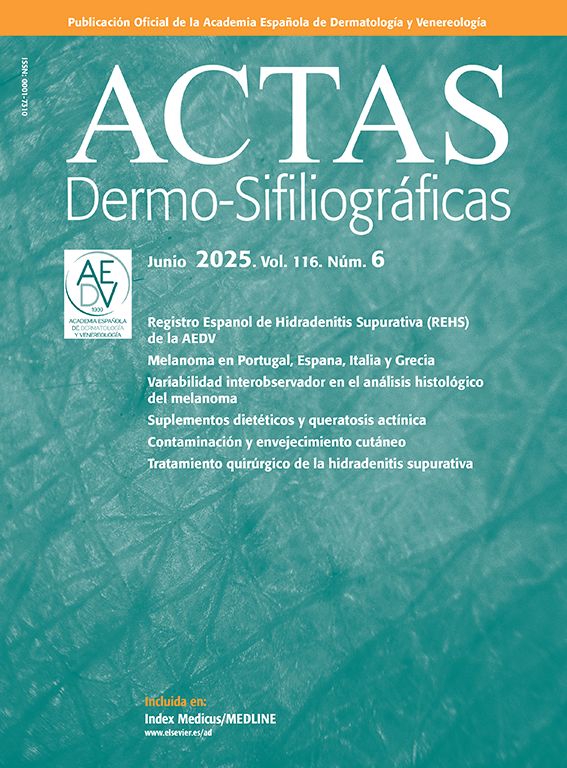

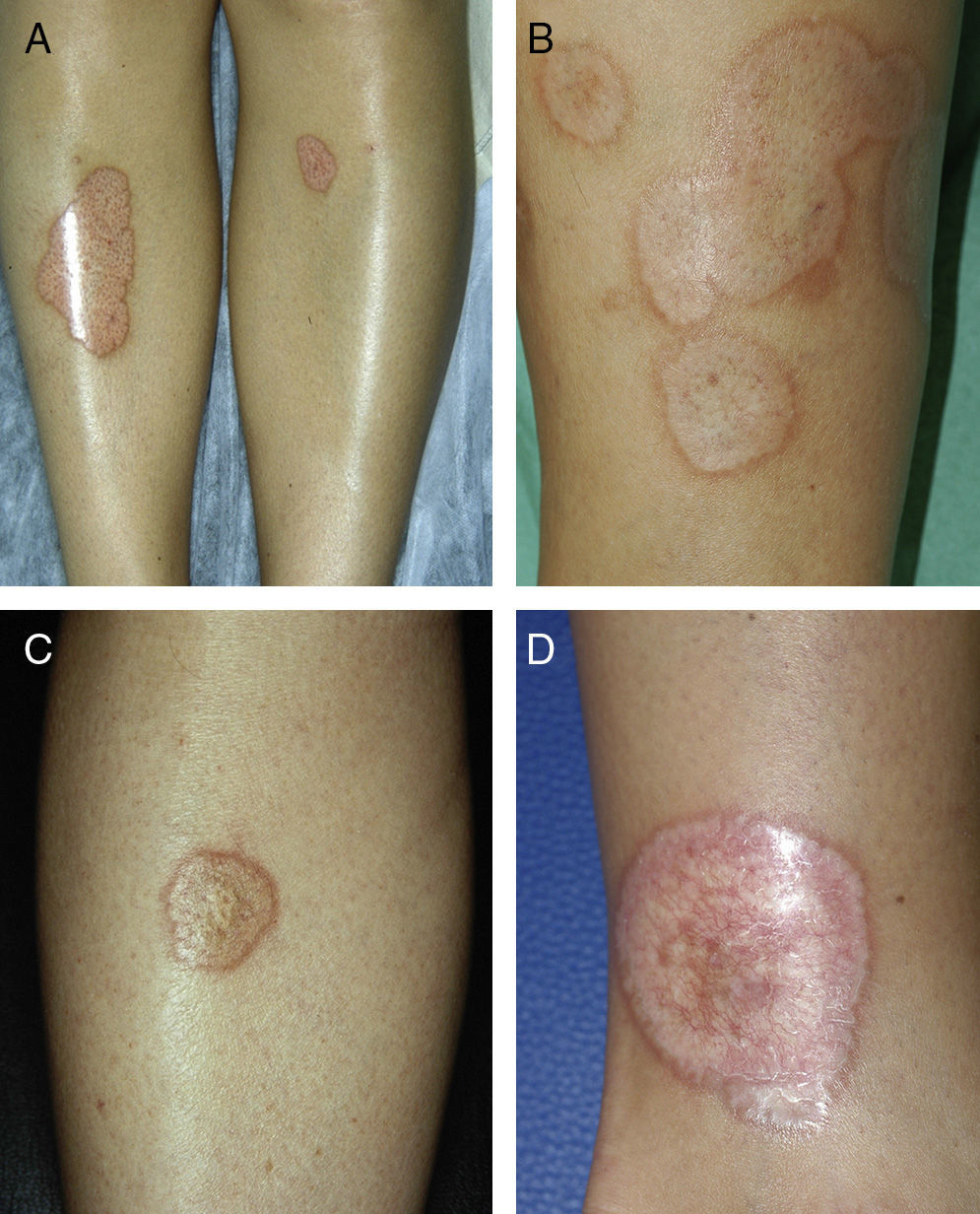

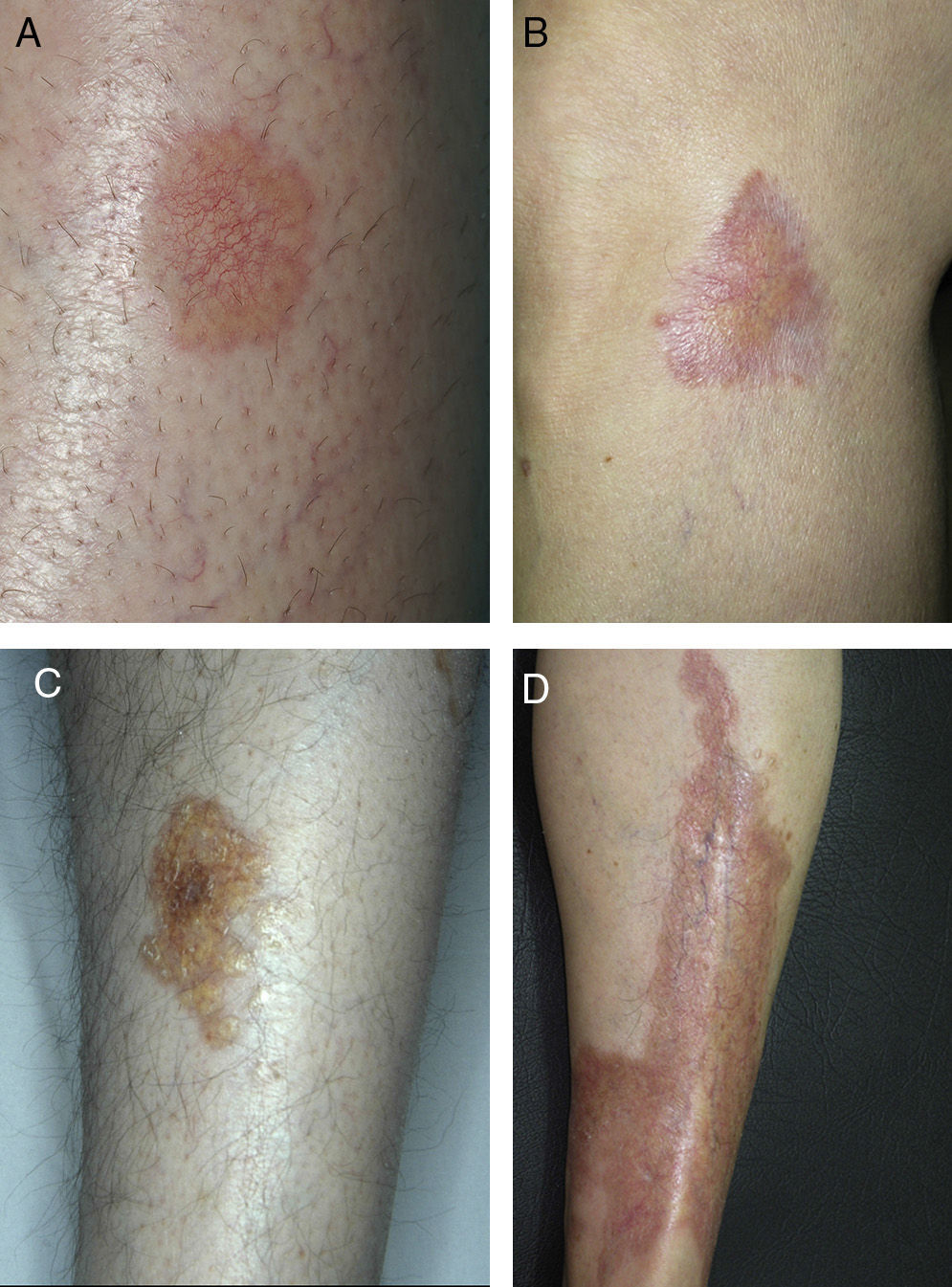

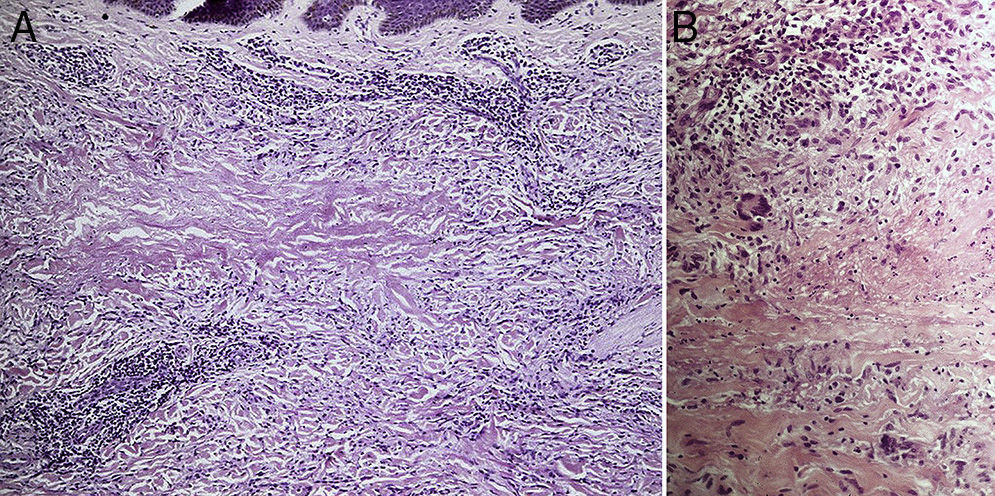

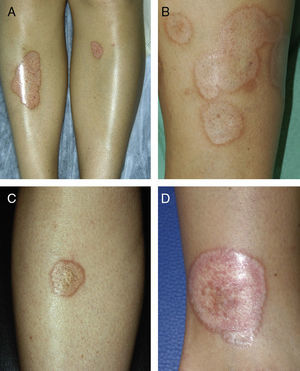

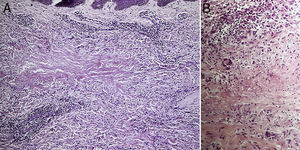

ResultsThe study population comprised 35 patients with NL (6 men and 29 women with a mean [SD] age of 47.20 years) who were treated and followed in the dermatology department (Table 1). Most had oval plaques with brownish borders and a yellowish, atrophic center. In some cases, the presence of perifollicular erythema or pigmentation gave the lesions a mottled appearance (Fig. 1). Prominent telangiectasias were common (Fig. 2). All of the patients had lesions on the lower extremities at diagnosis (involving the pretibial region in 31 cases) except for one patient who had a single lesion on the upper extremity and another with lesions resticted to the trunk. Only 2 patients had lesions at several sites. Thirteen patients (37%) had a single lesion at diagnosis, and the mean number of lesions was 3.37 (range, 1-12). The mean diameter was 7.74cm (range, 2-25cm). The lesions were ulcerated in 2 cases (Fig. 3). Histologically, all of the biopsy specimens revealed palisading granulomas surrounding areas of necrobiosis (Fig. 4).

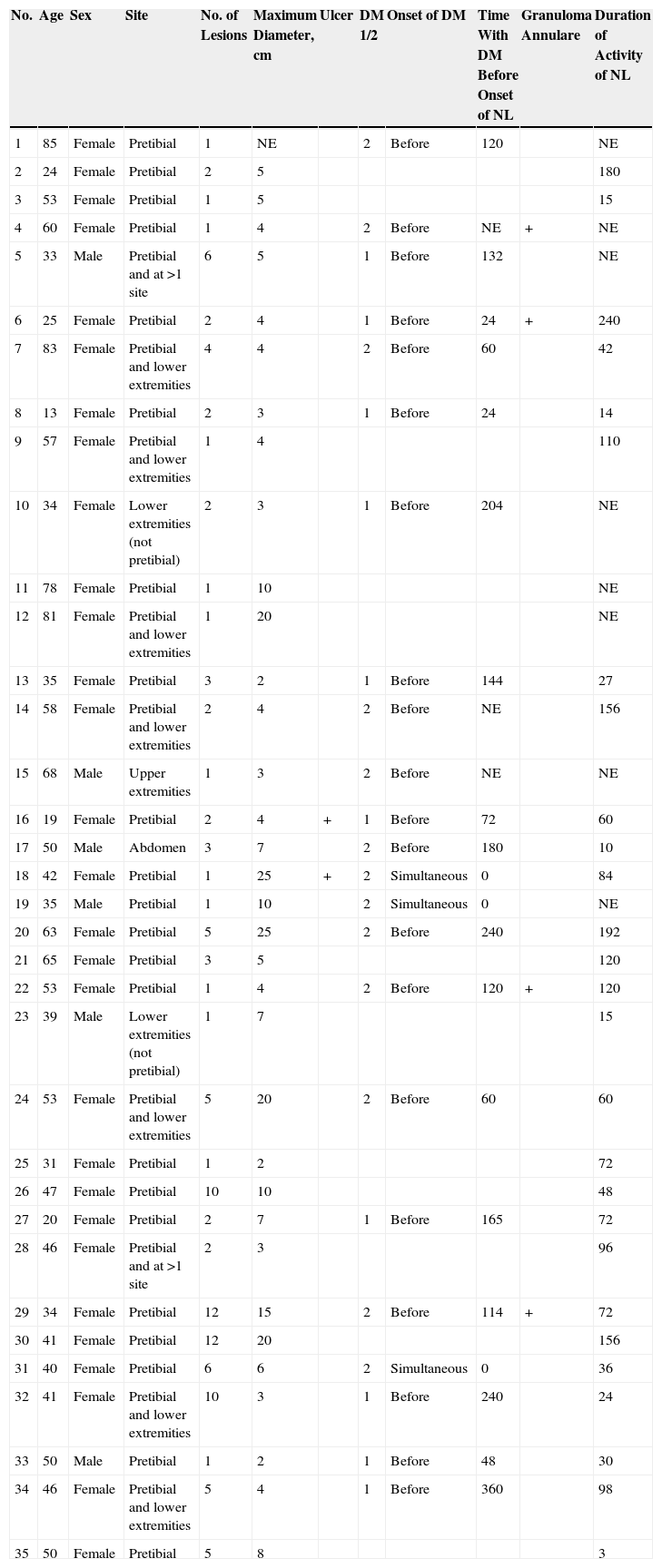

Clinical Data of the 35 Study Patients.

| No. | Age | Sex | Site | No. of Lesions | Maximum Diameter, cm | Ulcer | DM 1/2 | Onset of DM | Time With DM Before Onset of NL | Granuloma Annulare | Duration of Activity of NL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 85 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | NE | 2 | Before | 120 | NE | ||

| 2 | 24 | Female | Pretibial | 2 | 5 | 180 | |||||

| 3 | 53 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | 5 | 15 | |||||

| 4 | 60 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | 4 | 2 | Before | NE | + | NE | |

| 5 | 33 | Male | Pretibial and at >1 site | 6 | 5 | 1 | Before | 132 | NE | ||

| 6 | 25 | Female | Pretibial | 2 | 4 | 1 | Before | 24 | + | 240 | |

| 7 | 83 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 4 | 4 | 2 | Before | 60 | 42 | ||

| 8 | 13 | Female | Pretibial | 2 | 3 | 1 | Before | 24 | 14 | ||

| 9 | 57 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 1 | 4 | 110 | |||||

| 10 | 34 | Female | Lower extremities (not pretibial) | 2 | 3 | 1 | Before | 204 | NE | ||

| 11 | 78 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | 10 | NE | |||||

| 12 | 81 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 1 | 20 | NE | |||||

| 13 | 35 | Female | Pretibial | 3 | 2 | 1 | Before | 144 | 27 | ||

| 14 | 58 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 2 | 4 | 2 | Before | NE | 156 | ||

| 15 | 68 | Male | Upper extremities | 1 | 3 | 2 | Before | NE | NE | ||

| 16 | 19 | Female | Pretibial | 2 | 4 | + | 1 | Before | 72 | 60 | |

| 17 | 50 | Male | Abdomen | 3 | 7 | 2 | Before | 180 | 10 | ||

| 18 | 42 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | 25 | + | 2 | Simultaneous | 0 | 84 | |

| 19 | 35 | Male | Pretibial | 1 | 10 | 2 | Simultaneous | 0 | NE | ||

| 20 | 63 | Female | Pretibial | 5 | 25 | 2 | Before | 240 | 192 | ||

| 21 | 65 | Female | Pretibial | 3 | 5 | 120 | |||||

| 22 | 53 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | 4 | 2 | Before | 120 | + | 120 | |

| 23 | 39 | Male | Lower extremities (not pretibial) | 1 | 7 | 15 | |||||

| 24 | 53 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 5 | 20 | 2 | Before | 60 | 60 | ||

| 25 | 31 | Female | Pretibial | 1 | 2 | 72 | |||||

| 26 | 47 | Female | Pretibial | 10 | 10 | 48 | |||||

| 27 | 20 | Female | Pretibial | 2 | 7 | 1 | Before | 165 | 72 | ||

| 28 | 46 | Female | Pretibial and at >1 site | 2 | 3 | 96 | |||||

| 29 | 34 | Female | Pretibial | 12 | 15 | 2 | Before | 114 | + | 72 | |

| 30 | 41 | Female | Pretibial | 12 | 20 | 156 | |||||

| 31 | 40 | Female | Pretibial | 6 | 6 | 2 | Simultaneous | 0 | 36 | ||

| 32 | 41 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 10 | 3 | 1 | Before | 240 | 24 | ||

| 33 | 50 | Male | Pretibial | 1 | 2 | 1 | Before | 48 | 30 | ||

| 34 | 46 | Female | Pretibial and lower extremities | 5 | 4 | 1 | Before | 360 | 98 | ||

| 35 | 50 | Female | Pretibial | 5 | 8 | 3 |

Abbreviations: DM, diabetes mellitus; NE, nonevaluable; NL, necrobiosis lipoidica.

A, Extensive necrobiosis lipoidica with ulcerated areas and keratotic areas (patient 18). B, Necrobiosis lipoidica lesion that was previously ulcerated in the pretibial area and that has completely re-epithelialized (patient 16). C, Characteristic lesion of granuloma annulare in the clavicular area of patient 22. D, Disseminated granuloma annulare on the abdomen of patient 29.

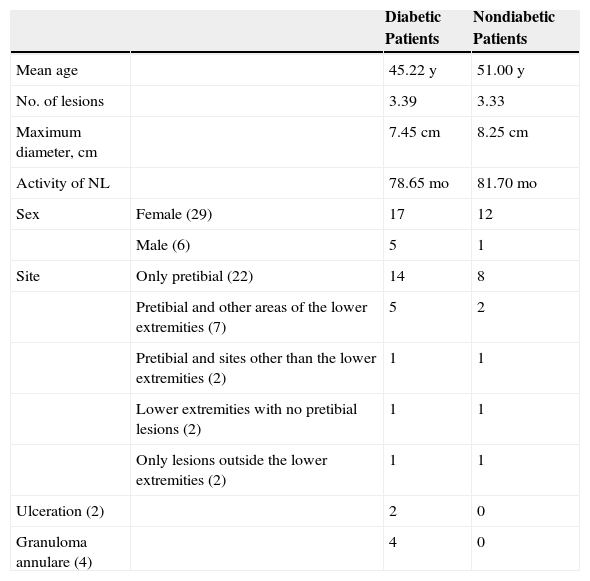

NL was associated with diabetes mellitus in 23 patients (65.71%). In 20 patients, the diagnosis of DM preceded that of NL by a mean of 135.70 months and was simultaneous in the remaining 3 patients. Ten patients had type 1 DM and 13 had type 2 DM. In no cases was the disease diagnosed during follow-up. The mean age of patients with DM was 45.22 years compared with 51.00 years for nondiabetic patients, although these differences were not statistically significant. The mean age of patients with type 1 DM, on the other hand, was significantly lower than that of patients with type 2 DM (31.60 vs 55.33 years; P<.001) and of that of the whole group (31.60 vs 53.44 years; P<.001). At diagnosis, the lesions had been present for 26.72 months, and the mean follow-up was 43.23 months. NL remained active for a mean of 79.70 months (Table 2).

Clinical Data: Association With Diabetes Mellitus.

| Diabetic Patients | Nondiabetic Patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 45.22 y | 51.00 y | |

| No. of lesions | 3.39 | 3.33 | |

| Maximum diameter, cm | 7.45cm | 8.25cm | |

| Activity of NL | 78.65 mo | 81.70 mo | |

| Sex | Female (29) | 17 | 12 |

| Male (6) | 5 | 1 | |

| Site | Only pretibial (22) | 14 | 8 |

| Pretibial and other areas of the lower extremities (7) | 5 | 2 | |

| Pretibial and sites other than the lower extremities (2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Lower extremities with no pretibial lesions (2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Only lesions outside the lower extremities (2) | 1 | 1 | |

| Ulceration (2) | 2 | 0 | |

| Granuloma annulare (4) | 4 | 0 |

Abbreviation: NL, necrobiosis lipoidica.

As for associated diseases, 6 patients had been diagnosed with hypothyroidism (4 of these patients already had type 1 DM), and 1 patient had chronic hepatitis C infection. NL was diagnosed simultaneously with pancreatic cancer in one patient and with sarcoidosis in another. Finally, 4 patients had lesions that were clinically and histologically typical of granuloma annulare (Fig. 3).

Twelve patients received no drugs during follow-up in our department. The remainder received at least 1 treatment, and most received several successive treatments owing to a lack of response. The most frequently administered treatment was topical 0.05% clobetasol propionate on the active border of the lesions but not in the atrophic center (14 cases). Intralesional infiltrations of triamcinolone acetonide (6) were also applied, as were topical tacrolimus (6) and phototherapy (3). Oral medication included pentoxifylline (11), ciclosporin (2 [because of ulcerated lesions in 1]), doxycycline (1), acetylsalicylic acid (1), and hydroxychloroquine (4). Most patients did not respond to the treatments administered. Only 3 patients responded to treatment. Oral pentoxifylline combined with ciclosporin was useful for treatment of ulcerated lesions in 1 case. Finally, 2 patients whose condition had not improved after receiving several treatments responded to hydroxychloroquine. In the remaining cases, the patients presented active lesions at the end of follow-up, except for 2 whose lesions remitted spontaneously leaving residual dyschromia.

DiscussionIn the present study of 35 patients with NL, we detected an association with DM in 23 (65.71%).

NL is an uncommon disease whose incidence is 3 times greater in females than in males.1 The characteristic lesions of NL consist of oval plaques with an indurated brown or violaceous border and a yellowish, atrophic center and are often accompanied by telangiectasias.2 In some cases in the present study, we observed perifollicular erythema or pigmentation, which gave the lesions a mottled appearance. We did not find this clinical characteristic in the literature and consider it typical of the lesions found in some of the patients in our study. The lesions are usually asymptomatic and are often multiple and bilateral.2 Solitary lesions at diagnosis have been reported in 16% to 27% of patients4,5; these lesions were somewhat more common in the present series (37%). Consistent with findings reported elsewhere, the lesions are usually limited to the lower extremities, especially the pretibial region. The finding of lesions at sites other than the lower extremities in 4 patients (11.4%) is similar to frequencies reported in the literature (7.7%-15%).2,5

The pathogenesis of NL is unknown. The association with DM suggests that NL could be due to microangiopathy secondary to glycoprotein deposits in vessel walls.1 Other theories suggest that NL could be caused by collagen fiber abnormalities,7 defective neutrophil migration,8 and tissue damage secondary to venous insufficiency.9

Although the incidence of NL is only 0.3%-1.2% in diabetic patients,1,10 DM is the most common associated disease. In the longest NL series published in 1956 and 1966, 42% and 65% of patients had DM the before diagnosis of NL.3,4 However, DM preceded NL in only 11% in a study published in 19995 and in 46% in a more recent study performed in Germany.6 Our findings confirm the results obtained in the oldest series, with a global incidence of 65.71%. Although the risk of developing DM after diagnosis of NL has been estimated at 6%,5 none of the patients in our study developed DM during follow-up. Consistent with results reported elsewhere,10 we observed a mean delay of more than 10 years (135.70 months) between diagnosis of DM and onset of the lesions of NL.

The clinical characteristics of NL differ little between diabetic and nondiabetic patients.4 Some authors highlight that patients with NL associated with type 1 DM are younger than other patients (mean age, 22 to 49 years).10 In the present study, the mean age of patients with type 1 DM was significantly lower than that of the group comprising patients with type 2 DM and nondiabetic patients. These differences can be attributed to the lower age at onset of type 1 DM and support a direct association between DM and NL. However, we were unable to detect other significant differences between diabetic and nondiabetic patients or between patients with type 1 DM and patients with type 2 DM.

NL has been associated with diseases other than DM, such as Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis, rheumatoid arthritis, monoclonal gammopathy, granuloma annulare, and sarcoidosis, as well as with jejunal bypass surgery.1,2 We observed an association between NL and granuloma annulare in 4 patients, all of whom had diabetes. Such a finding is not surprising, since granuloma annulare has also been linked to DM and, like NL, is associated with palisading granulomas. Consequently, differential diagnosis can sometimes prove difficult. However, in NL, palisading granulomas are horizontally arranged in the dermis. They also present necrobiotic collagen and an inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells. The presence of mucin, on the other hand, is more indicative of granuloma annulare. Similarly, it is not surprising that NL is occasionally associated with other granulomatous diseases of unknown origin, such as sarcoidosis and Crohn disease. However, potential associations reported in the literature have no clear pathogenic explanation and may be random rather than genuine. For example, in some patients, NL has been reported to be associated with autoimmune thyroid disease,11,12 and it has been suggested that the antibodies responsible for the thyroid disorder cause NL in these cases.11 A recent study showed the presence of thyroid dysfunction in 13% of 52 cases of NL, while the estimated prevalence in the general population is 5.5%.6 Although 6 patients in our study (17%) had hypothyroidism, this association may be due to the co-occurrence of autoimmune thyroid disease and type 1 DM, since 4 of the 6 patients also had type 1 DM.

No treatment has proven effective against NL in clinical trials. In any case, response to treatment could be difficult to evaluate, given that spontaneous remission can occur in 17% of patients.4 Since 2002, there have been reports of patients who responded well to antimalarial drugs.13–16 The retrospective design of our study and the limited number of patients prevented us from comparing treatments with placebo; nevertheless, we feel that hydroxychloroquine played a role in remission of the lesions in 2 patients who had not improved after several previous treatments.

The results obtained in the present study confirm that NL is frequently associated with both type 1 and type 2 DM and that, even though DM usually occurs some years before NL, both diseases can appear simultaneously. Despite the fact that none of the patients in our study developed DM during follow-up, patients with NL should be informed about the possibility of developing DM in the future.

Ethical DisclosuresProtection of Persons and AnimalsThe authors declare that this research did not involve experiments performed on humans or animals.

Confidentiality of DataThe authors declare that they have followed their hospital's protocol on the publication of data concerning patients.

Right to PrivacyThe authors declare that no private patient data are disclosed in this article.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Marcoval J, Gómez-Armayones S, Valentí-Medina F, Bonfill-Ortí M, Martínez-Molina L. Necrobiosis lipoídica. Estudio descriptivo de 35 pacientes. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:402–407.