Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an uncommon heterogeneous group of autoimmune subepidermal blistering disorders which predominantly involves mucosal membranes. Diagnosis and treatment are challenging and delay may cause severe scarring and complications such as esophageal and urethral stenosis, conjunctival synechia and blindness.

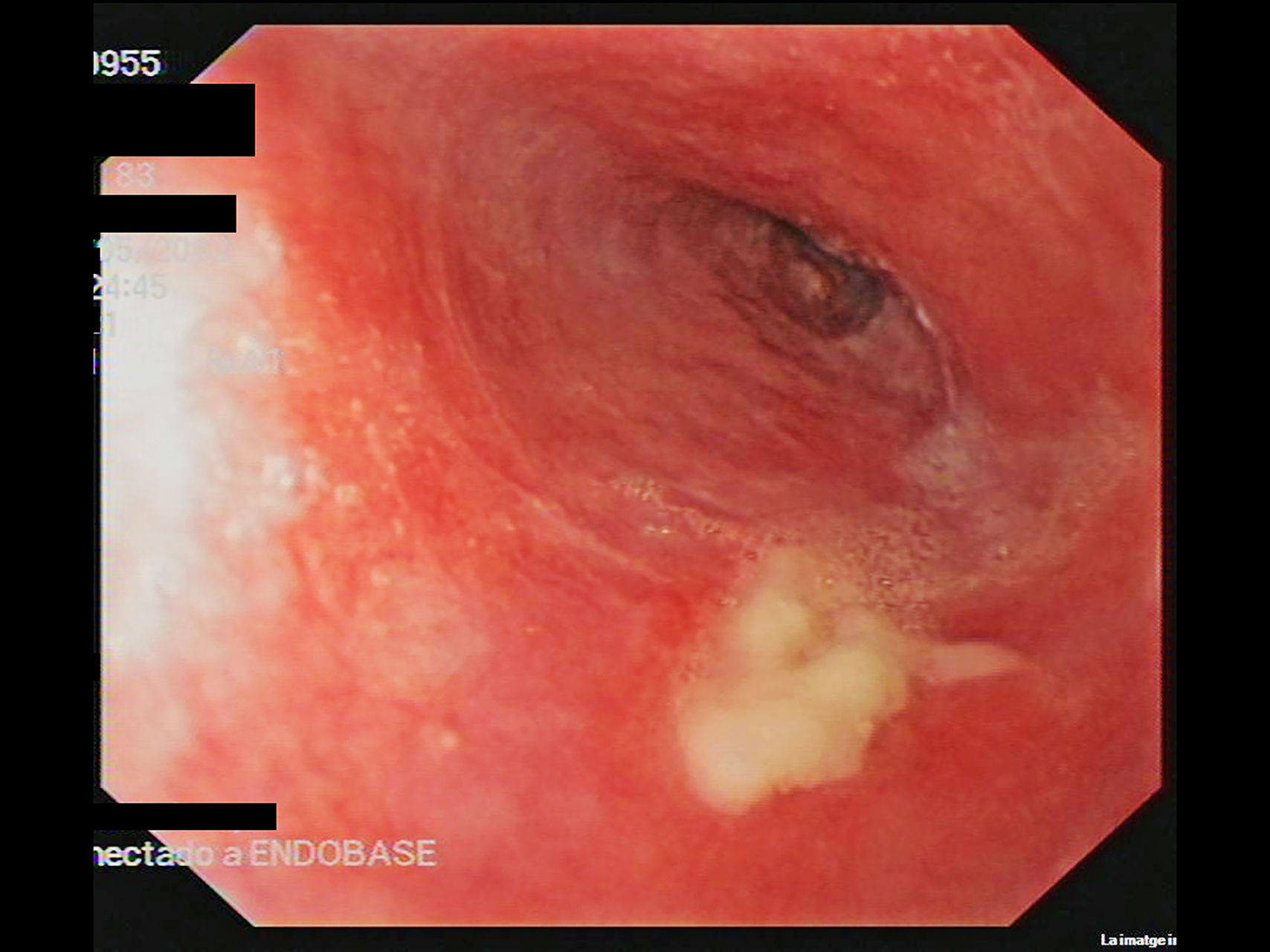

An 88-year-old woman with a 9-year history of dysphagia secondary to an indeterminate esophageal stenosis, requiring several endoscopic dilatations (Fig. 1), was referred to our clinic for evaluation of oral erosions. Examination revealed erosive gingivitis, and extensive oral and genital erosions (Fig. 2). Biopsies of vulvar lesions were non-specific and direct immunofluorescence (IFD) of non-affected genital and labial mucosa were negative. Indirect immunofluorescence on salt-split skin (IIF) revealed IgG antibodies binding to the epidermal side of the blister. IIF showed IgG deposition at the basement membrane. ELISA tests were negative for anti Dg1, Dg3 and BP180 antibodies. Immunoblotting of non-affected epidermal extracts was negative for IgG: BP230, BP180, 210kDa envoplakin, 190kDa periplakin, Dg1 and Dg3. Immunoblotting of recombinant protein of C-terminal domain of BP180 (BP180ct) detected IgG reactivity of patient serum. A diagnosis of MMP was established and treatment with prednisone (30mg/day) in a tapering regimen, dapsone 50mg/day and tacrolimus in a 2mg/liter mouth rinse formulation was initiated. Dysphagia, oral and genital erosions remitted, but the patient has developed a scarring fibrosis of the vulva with fusion of labia and urethral meatus.

Erosive esophagitis (EE) is a common finding in esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), drug-induced mucosal damage, infections, malignancies and autoimmune disorders.1 Among autoimmune disorders, a possible underdiagnosed pathology is MMP. The frequency of esophageal involvement in MMP is between 2% and 30%, and this may be an underestimation as EGD is only performed on symptomatic patients.2

In patients with MMP and esophageal lesions, a mean of another 3 mucosal areas are involved, and the oral cavity is affected in 86 % of the cases.3 Dysphagia can signal esophageal involvement, although clinically it can be difficult to distinguish it from odynophagia. For all the above-mentioned reasons, performing an EGD on every newly diagnosed patient with MMP has been suggested.2,4 Although, EGD is not free of complications and not always available, we agreed with other authors2–4 that it should be especially indicated in symptomatic patients or patients with involvement of several mucous membranes.

The mouth is the beginning and the most accessible portion of the digestive tract, and as EGD is performed with a transnasal videogastroscope in these patients, oral exploration may be omitted. In any patient with esophageal erosions, scarring or stenosis, the oral cavity must be clinically explored. The presence of gingivitis or erosions makes examining the anogenital area, nose, throat, eyes and skin necessary in order to rule out MMP, and to evaluate the severity of the disease.

Diagnosis and treatment of MMP can be challenging. In our patient, IIF revealed an epidermal side positivity, which is compatible with bullous pemphigoid, lichen planus pemphigoides and MMP. This finding excludes the diagnosis of acquired bullous epidermolysis, P200 pemphigoid and MMP anti-laminin 332.5 Finally, immunoblotting was positive for BP180ct, a very specific finding of MMP.6 On the basis of clinical, pathological and molecular features, a diagnosis of MMP was made.

First-line therapies for MMP include systemic corticosteroids, usually in combination with other immunosuppressive treatments.7 Dapsone or methotrexate can be considered in mild-to-moderate stages.8 In more severe cases, particularly in ocular involvement, cyclophosphamide has been used in monthly intravenous low-dose pulsed 500mg with good outcomes and with better tolerance than continuous regimen.9 Off-label use of anti-TNF and especially, anti-CD20 with or without intravenous immunoglobulins, have also been described in recalcitrant cases with satisfactory results, but frequent relapses.7

In conclusion, multidisciplinary management is indispensable to achieve a rapid diagnosis and a better assessment of the disease extension and severity, identifying early involvement of high-risk areas such as the larynx, eye and esophagus, which require more aggressive therapies.10

We are very grateful to Dr. JM Mascaró Jr. from Hospital Clínic (Barcelona), Dr. N. Ishii from Kurume University School of Medicine (Fukoka) and Dr. T. Hashimoto from University Graduate School of Medicine (Osaka) for their help with this case.

Please cite this article as: Corral-Magaña O, Morgado-Carrasco D, Fustà-Novell X, Iranzo P. Penfigoide de mucosas: cuando la mucosa oral puede ser la clave para el diagnóstico de una estenosis esofágica de origen desconocido. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ad.2019.04.011