Management of hand eczema is complex because of the broad range of different pathogeneses, courses, and prognoses. Furthermore, the efficacy of most available treatments is not well established and the more severe forms can have a major impact on the patient's quality of life. Patient education, preventive measures, and the use of emollients are the mainstays in the management of hand eczema. High-potency topical corticosteroids are the treatment of choice, with calcineurin inhibitors used for maintenance. Phototherapy or systemic treatments are indicated in patients who do not respond to topical treatments. Switching from topical treatments should not be delayed to avoid sensitizations, time off work, and a negative impact on quality of life. Alitretinoin is the only oral treatment approved for use in chronic hand eczema.

El manejo del eczema de manos es complejo, ya que engloba eczemas de etiopatogenia, curso y pronóstico muy diferentes; la mayoría de tratamientos disponibles no cuentan con niveles de eficacia establecidos, y en sus formas graves la calidad de vida se afecta de forma importante. La educación del paciente, las medidas de protección y el uso de emolientes constituyen un pilar fundamental en el abordaje de estos pacientes. Los corticoides tópicos de alta potencia son el tratamiento de elección, seguidos de los inhibidores de la calcineurina para el mantenimiento de la enfermedad. En los casos refractarios a estos tratamientos deberíamos utilizar la fototerapia o tratamientos sistémicos, los cuales no deberían demorarse para evitar sensibilizaciones, bajas laborales y alteración en la calidad de vida. La alitretinoína es el único tratamiento oral disponible que ha sido aprobado para su utilización en el eczema crónico de manos.

Hand eczema or dermatitis is a skin condition that exclusively or primarily involves the hands. It is a common condition, with an estimated annual prevalence of 10% to 14%,1,2 and an incidence of between 5.5 and 8.8 cases per 1000 person-years.3–5 It is also the most common occupational disease in many countries.6

Adequate management of severe, chronic hand eczema is one of the main challenges in this condition. Chronic hand eczema is eczema that lasts for more than 3 months or occurs at least twice a year despite adequate treatment and treatment adherence, while severe eczema is extensive, long-standing or recurrent eczema that features cracks, severe lichenification, and/or induration.7,8 Just 5% to 7% of cases of hand eczema are considered severe and 2% to 4% are refractory to topical treatment.9 Nevertheless, up to 70% of cases of chronic hand eczema are severe or very severe,10 and therefore from a practical perspective, chronic hand eczema is comparable to severe hand eczema. Severe chronic hand eczema has a considerable occupational, domestic, social, and psychological impact.

Chronic hand eczema is associated with major quality of life impairment, as it impedes patients from doing certain activities and is also surrounded by the stigma that comes with its location in such a visible part of the body. These difficulties lead to additional problems such as changes to and abandonment of regular activities and hobbies, sleep disorders, and more serious conditions such as anxiety, social phobia, and depression. Accordingly, chronic hand eczema is placed just behind atopic dermatitis and psoriasis in terms of impact on patient quality of life.11–15 Chronic hand eczema is also associated with considerable occupational disability.9 According to some studies, it is estimated to be responsible for 19.9% of cases of prolonged sick leave and 23% of cases of job loss,16 with associated costs of more than €1.5 billion a year in some countries.17 It is therefore remarkable that just 50% of patients with hand eczema see a doctor about their condition.12,18,19

The management of chronic hand eczema is complex, largely because it has very different causes, courses, and prognoses. An accurate diagnosis is therefore essential (Table 1), and it is also important to classify the eczema where possible. It should be noted, however, that there is no universal classification system for hand eczema, although many systems have been proposed.5,7–9,20–24 We believe that hand eczema should at least be classified etiologically (Table 2) and morphologically (Table 3), although there is no specific correlation and multiple factors are frequently involved.

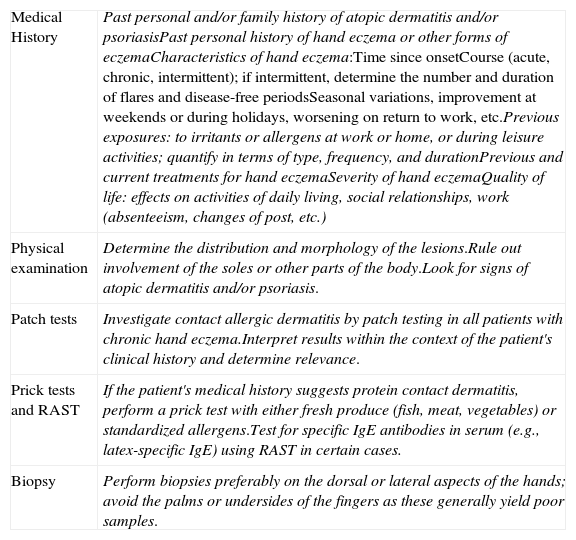

Diagnostic Evaluation of Hand Eczema.

| Medical History | Past personal and/or family history of atopic dermatitis and/or psoriasisPast personal history of hand eczema or other forms of eczemaCharacteristics of hand eczema:Time since onsetCourse (acute, chronic, intermittent); if intermittent, determine the number and duration of flares and disease-free periodsSeasonal variations, improvement at weekends or during holidays, worsening on return to work, etc.Previous exposures: to irritants or allergens at work or home, or during leisure activities; quantify in terms of type, frequency, and durationPrevious and current treatments for hand eczemaSeverity of hand eczemaQuality of life: effects on activities of daily living, social relationships, work (absenteeism, changes of post, etc.) |

| Physical examination | Determine the distribution and morphology of the lesions.Rule out involvement of the soles or other parts of the body.Look for signs of atopic dermatitis and/or psoriasis. |

| Patch tests | Investigate contact allergic dermatitis by patch testing in all patients with chronic hand eczema.Interpret results within the context of the patient's clinical history and determine relevance. |

| Prick tests and RAST | If the patient's medical history suggests protein contact dermatitis, perform a prick test with either fresh produce (fish, meat, vegetables) or standardized allergens.Test for specific IgE antibodies in serum (e.g., latex-specific IgE) using RAST in certain cases. |

| Biopsy | Perform biopsies preferably on the dorsal or lateral aspects of the hands; avoid the palms or undersides of the fingers as these generally yield poor samples. |

Abbreviations: IgE, immunoglobulin E; RAST, radioallergosorbent test.

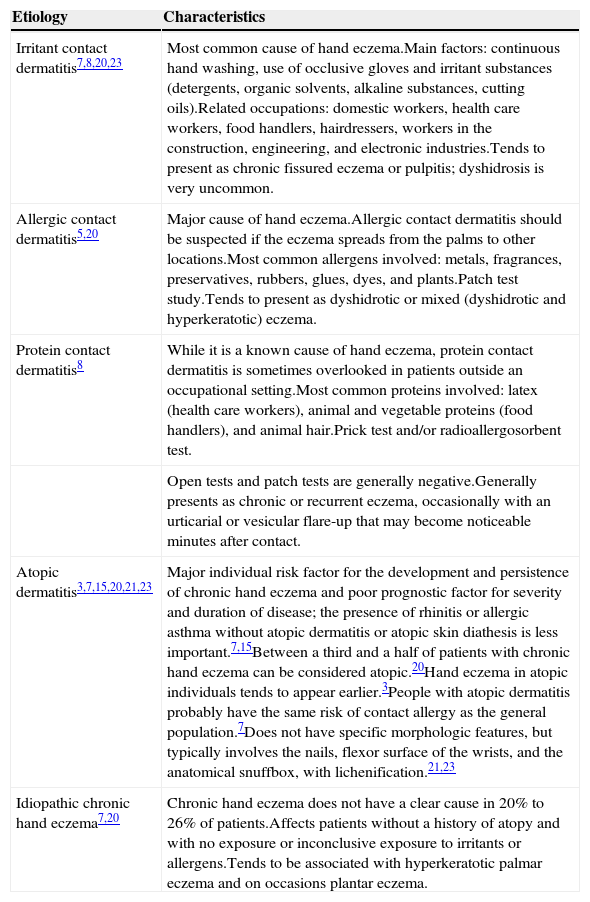

Etiological Classification of Hand Eczema.

| Etiology | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Irritant contact dermatitis7,8,20,23 | Most common cause of hand eczema.Main factors: continuous hand washing, use of occlusive gloves and irritant substances (detergents, organic solvents, alkaline substances, cutting oils).Related occupations: domestic workers, health care workers, food handlers, hairdressers, workers in the construction, engineering, and electronic industries.Tends to present as chronic fissured eczema or pulpitis; dyshidrosis is very uncommon. |

| Allergic contact dermatitis5,20 | Major cause of hand eczema.Allergic contact dermatitis should be suspected if the eczema spreads from the palms to other locations.Most common allergens involved: metals, fragrances, preservatives, rubbers, glues, dyes, and plants.Patch test study.Tends to present as dyshidrotic or mixed (dyshidrotic and hyperkeratotic) eczema. |

| Protein contact dermatitis8 | While it is a known cause of hand eczema, protein contact dermatitis is sometimes overlooked in patients outside an occupational setting.Most common proteins involved: latex (health care workers), animal and vegetable proteins (food handlers), and animal hair.Prick test and/or radioallergosorbent test. |

| Open tests and patch tests are generally negative.Generally presents as chronic or recurrent eczema, occasionally with an urticarial or vesicular flare-up that may become noticeable minutes after contact. | |

| Atopic dermatitis3,7,15,20,21,23 | Major individual risk factor for the development and persistence of chronic hand eczema and poor prognostic factor for severity and duration of disease; the presence of rhinitis or allergic asthma without atopic dermatitis or atopic skin diathesis is less important.7,15Between a third and a half of patients with chronic hand eczema can be considered atopic.20Hand eczema in atopic individuals tends to appear earlier.3People with atopic dermatitis probably have the same risk of contact allergy as the general population.7Does not have specific morphologic features, but typically involves the nails, flexor surface of the wrists, and the anatomical snuffbox, with lichenification.21,23 |

| Idiopathic chronic hand eczema7,20 | Chronic hand eczema does not have a clear cause in 20% to 26% of patients.Affects patients without a history of atopy and with no exposure or inconclusive exposure to irritants or allergens.Tends to be associated with hyperkeratotic palmar eczema and on occasions plantar eczema. |

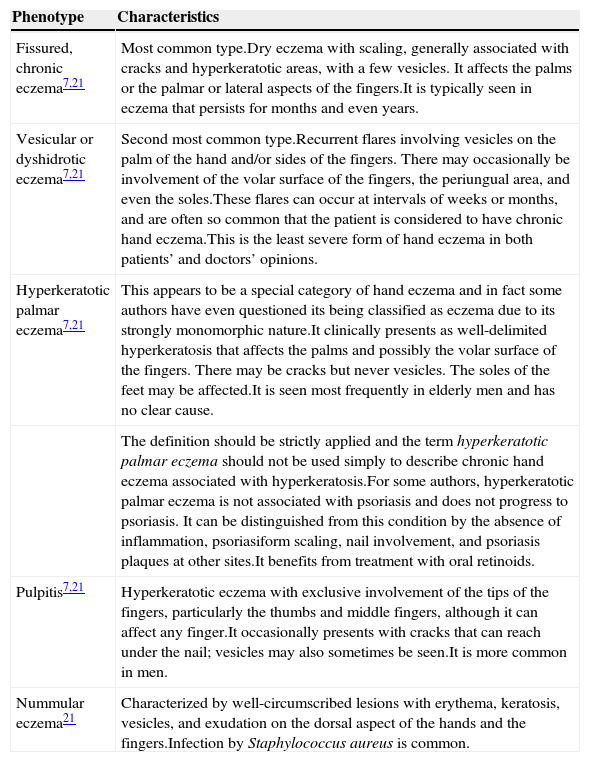

Morphologic Classification of Hand Eczema.

| Phenotype | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Fissured, chronic eczema7,21 | Most common type.Dry eczema with scaling, generally associated with cracks and hyperkeratotic areas, with a few vesicles. It affects the palms or the palmar or lateral aspects of the fingers.It is typically seen in eczema that persists for months and even years. |

| Vesicular or dyshidrotic eczema7,21 | Second most common type.Recurrent flares involving vesicles on the palm of the hand and/or sides of the fingers. There may occasionally be involvement of the volar surface of the fingers, the periungual area, and even the soles.These flares can occur at intervals of weeks or months, and are often so common that the patient is considered to have chronic hand eczema.This is the least severe form of hand eczema in both patients’ and doctors’ opinions. |

| Hyperkeratotic palmar eczema7,21 | This appears to be a special category of hand eczema and in fact some authors have even questioned its being classified as eczema due to its strongly monomorphic nature.It clinically presents as well-delimited hyperkeratosis that affects the palms and possibly the volar surface of the fingers. There may be cracks but never vesicles. The soles of the feet may be affected.It is seen most frequently in elderly men and has no clear cause. |

| The definition should be strictly applied and the term hyperkeratotic palmar eczema should not be used simply to describe chronic hand eczema associated with hyperkeratosis.For some authors, hyperkeratotic palmar eczema is not associated with psoriasis and does not progress to psoriasis. It can be distinguished from this condition by the absence of inflammation, psoriasiform scaling, nail involvement, and psoriasis plaques at other sites.It benefits from treatment with oral retinoids. | |

| Pulpitis7,21 | Hyperkeratotic eczema with exclusive involvement of the tips of the fingers, particularly the thumbs and middle fingers, although it can affect any finger.It occasionally presents with cracks that can reach under the nail; vesicles may also sometimes be seen.It is more common in men. |

| Nummular eczema21 | Characterized by well-circumscribed lesions with erythema, keratosis, vesicles, and exudation on the dorsal aspect of the hands and the fingers.Infection by Staphylococcus aureus is common. |

The goal of primary prevention is to help prevent hand eczema in healthy individuals; this is particularly important in occupational settings, although prevention is still not a priority in many industries.25 Prevention strategies include a) avoidance or substitution of harmful substances through legislative changes (e.g., regulation of chromium content in cement or preservatives in cosmetics); b) measures to contain or isolate potential irritants (e.g., ventilation systems); c) use of personal protection measures such as gloves and barrier creams; d) identification of susceptible individuals through questionnaires and/or patch testing, although these measures are controversial; and e) education programs at the workplace, which have proven to be both beneficial and cost-effective.25

Secondary PreventionSecondary prevention essentially revolves around the early detection of the first symptoms of hand eczema. Early referral to a dermatology unit is therefore crucial.17 The main aim of secondary prevention is to inform the patient. Patients should be educated about hand eczema, with the creation of realistic expectations about the disease and its treatments, and advice about lifestyle changes such as skin care, avoidance of irritants and allergens, and use of protection measures.5,7,8 This information should be explained in person and also provided in writing (Table 4).5 Theoretical-practical seminars given in some countries have proven to be effective in terms of reducing the prevalence and severity of eczema in the long term (1 year).8,17,26

Written Information Leaflet for Patients.

| What is hand eczema? |

| Hand eczema or dermatitis is an inflammation of the skin of the hands. Affected hands tend to be red, dry, and rough; there may also be scales, cracks, and sometimes even small fluid-filled blisters. Patients typically complain of dryness, tightness, and itching or even pain. The most commonly affected sites are the palms of the hands, followed by the fingers and the back of the hands. It is not a contagious disease. |

| What types of hand eczema are there? |

| There are 2 main types of hand eczema: |

| Irritant hand eczema. This is caused by repeated contact between the skin and irritant substances, such as soap and water in individuals who wash their hands frequently, detergents, caustic agents (e.g., bleach), etc. Humidity, occlusion (e.g., use of gloves), sweat, and friction also have a role. This is the most common type of hand eczema and can affect anyone exposed to these situations or substances. |

| Allergic hand eczema. This is caused by contact with a substance to which the person is already allergic. It must be confirmed by allergy tests (patch tests), but these are not always indicated. These allergies tend to last for a lifetime and patients therefore need to avoid the substance to which they are allergic. |

| What should I do to avoid or improve my hand eczema? |

| Hand-washing |

| Do not wash your hands excessively. If your job requires frequent hand-washing (for instance if you are a health care worker), use an alcohol-based disinfectant instead of soap and water. |

| Avoid using very hot water, even if wearing gloves. It is better to use warm water. |

| Avoid harsh or scented soaps. It is preferable to use soapless, unscented products. |

| Take off rings before wet work or hand-washing, as these tend to retain irritants. |

| It is better to pat rather than rub your hands dry. |

| Apply moisturizers after washing your hands. When your skin is very dry, very greasy (ointment-based) moisturizers seem to work best, but these are sticky and may not be practical for everyday use. |

| Avoid irritant and allergenic substances |

| Avoid contact with irritant substances, such as soaps, detergents, caustic substances (e.g., bleach), solvents, scrubs, etc. |

| Use vinyl gloves when shampooing your hair. If this is not possible, use the hand that is less likely to be affected by eczema. |

| When preparing food, try to minimize contact with fruit juice, fruit, vegetables, raw meat, onion, and garlic. |

| Use a long-handled brush for washing dishes, or where possible, use a dishwasher. |

| If you find out that you are allergic to something in an allergy test, you must avoid this substance and make sure that it is not present in any of the products you use. |

| Glove use |

| Wear cotton gloves under rubber gloves, as sweating tends to make eczema worse. |

| Use cotton gloves to do general house work (e.g., dusting) or to handle material or cardboard. |

Source: Adapted from English et al.5

Patients need to be educated on the use of barrier creams and moisturizers.27–30 It is important to use fragrance-free products and products that do not contain preservatives that have most frequently proven to be allergenic.7,8

Barrier creams are designed to create a protective layer, but the effectiveness of many of these creams is based not only on the physical barrier they provide, but also on their active ingredients (astringents, UV absorbers, and complexing agents). A more accurate term would therefore be protection creams. These creams protect against common irritants (e.g., water and detergents), epoxy resins, metals, paints, and cutting oils, and artificial and natural UV light. Additionally, they keep the skin cleaner and facilitate the use of gloves. When applied to irritated skin, however, they can aggravate the eczema and should therefore only be used on healthy skin.25,31

Moisturizers and emollients act by restoring the corneal layer of the epidermis.25 There is both clinical and experimental evidence that lipid-rich moisturizers can favor healing and prevent recurrences of hand eczema.32,33 There are 2 types of moisturizers: those that provide a semi-occlusive layer and those that include moisturizing substances (these are more effective).34 The creams can be applied as often as necessary, but at least after hand-washing and before going to bed. When intensive treatment is needed, the moisturizers can be covered by an occlusive dressing.23

Information About Allergies and IrritantsPatients should also be informed about their allergies, the role these have in their eczema, and measures to avoid or minimize contact.7 They should be taught the importance of identifying irritating activities such as excessive hand-washing and told that alcohol-based handrubs are less irritant than soap and water.35–37

Instructions About Protection MeasuresPatients should wear gloves when doing dirty or wet at home or at work (e.g., cleaning, preparing food, etc.) and be advised to wear these as often as necessary but for the shortest time possible. Latex gloves offer good protection against microorganisms and water-based materials, but they have little effect in protecting against fats, solvents, and chemicals in general. Nitrile gloves, by contrast, offer good protection against fats and solvents, while vinyl gloves offer additional protection against most chemical substances. Vinyl gloves are therefore preferable to latex gloves, but for optimal results they should be worn over cotton gloves. There are also special occupational gloves for handling substances that can penetrate vinyl (e.g., methacrylate, aromatic or chlorinated solvents, esters). Examples are polyvinyl alcohol gloves and Viton or butyl gloves.7,23,38

Tertiary PreventionTertiary prevention is indicated for patients with chronic and/or severe hand eczema that is refractory to multiple treatments and in which secondary prevention measures have proven insufficient. The main goals of tertiary prevention are to reduce the severity of disease and the use of corticosteroids, shorten sick leave duration, reduce absenteeism, and improve patient quality of life. A multidisciplinary approach involving dermatologists, occupational physicians, psychologists, and insurance companies is needed in such cases.8,39

Several authors have proposed a model known as the Osnabrück Model, which combines a hospital stay of 2 to 3 weeks for diagnosis, dermatological treatment, and educational and psychological advice, followed by a home treatment period of 2 to 3 weeks to allow full skin barrier recovery and enable the patient to return to work. This model has proven effective in both the short and long term.17,39

TreatmentTreatment of chronic hand eczema should be individualized. While numerous treatment modalities exist, reliable clinical studies are lacking with which to produce clinical guidelines based on sufficient evidence. In the next section, we discuss the treatments available and the corresponding level of supportive evidence based on the grading system proposed by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine.40

Topical TreatmentsMost patients can be adequately managed with a combination of protection measures and topical treatments.

Topical CorticosteroidsTopical corticosteroids are the treatment of choice (level of evidence 1c, i.e., demonstrated in clinical practice). However, there are several additional considerations that must be taken into account.5,8,41,42

- 1.

The potency of the corticosteroids and duration of treatment will depend on the severity of the eczema and its location. In general, because eczema tends to affect areas of the skin with a thick stratum corneum, and because of the risk of recurrence, high- or very high–potency corticosteroids are the treatment of choice.

- 2.

The vehicle will depend on morphology and disease phase. Creams should be used in acute eczema or eczema with vesiculation, while ointments should be used for chronic eczema or eczema with lichenification.

- 3.

Corticosteroids should be used for short periods of time because of their adverse effects, in particular, skin atrophy and skin barrier alterations, which interfere with stratum corneum repair.

- 4.

Fungal infections should be ruled out before treatment is started.

- 5.

If the eczema worsens, the possibility of allergic contact dermatitis to the topical corticosteroid or any of its ingredients should be investigated and patch tests performed.

As a general rule thus, high-potency corticosteroids (clobetasol propionate, mometasone furoate, betamethasone valerate) should be applied once daily for 2 to 4 weeks. If subsequent treatment is considered necessary, an intermittent maintenance regimen consisting of 2 to 3 applications a week has been proven to be both effective and safe.7,43–45

Calcineurin InhibitorsThe effectiveness and safety of calcineurin inhibitors is well established in atopic dermatitis, but few studies have evaluated the effectiveness of these drugs in hand eczema, and those that have have studied small series of patients and performed few comparative studies (level of evidence 2b, i.e., low-quality clinical studies). Calcineurin inhibitors generally improve the clinical signs of dermatitis and the associated pruritus, and they also appear to delay recurrences.46–53 They are well tolerated, and the most common adverse effect is a transient burning sensation, which is more common with tacrolimus. Tacrolimus is probably the calcineurin inhibitor of choice due to its greater potency and oil-based formulation.54

Three clinical trials have compared the efficacy of a calcineurin inhibitor (pimecrolimus) with a vehicle cream. The first of these, which involved 294 patients with chronic hand eczema, showed superior results for pimecrolimus,49 but the other 2 trials, one with 652 patients with mild to moderate chronic hand eczema52 and the other with 40 patients with atopic hand eczema,53 found no significant differences between the treatments tested. Just 1 study has compared a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus) and a corticosteroid (mometasone furoate), and showed a 50% improvement for both treatments. Although the study involved just 16 patients, who in addition had a specific type of eczema (moderate to severe dyshidrotic palmoplantar eczema), its results suggest the possibility of a rotational treatment regimen combining a calcineurin inhibitor and corticosteroids for long-standing chronic hand eczema.46

We can therefore conclude that calcineurin inhibitors are useful in chronic hand eczema, but not in terms of achieving remission but rather in reducing the need for corticosteroids. Calcineurin inhibitors and corticosteroids could therefore be combined for longer treatment regimens, with the former used for more stable phases and the latter used for flares.

Other Topical TreatmentsTopical antibiotics and antiseptics such as chlorhexidine are useful for eczema with secondary infection, but they can cause allergic contact dermatitis, and therefore certain authors recommend using oral antibiotics instead.8 Bexarotene gel 1% used alone resulted in at least 90% clearance of the hands in 39% of patients and was well tolerated.55 Iontophoresis with tap water is effective for dyshidrotic hand eczema, particularly in patients with hyperhidrosis.56 Botulinum toxin has proven to be effective in 2 studies, with superior results seen in patients with palmar hyperhidrosis or worsening of their eczema in summer months.57–59 Grenz ray therapy has also been proposed as a simple, economic, effective, and safe treatment when administered according to recommended guidelines.60 All the above treatments are supported by a level of evidence of 4.

PhototherapyPhototherapy is a good option for hand eczema that is refractory to topical corticosteroids, although this is based more on clinical experience than on scientific evidence (evidence level 1c), although its efficacy has been proven in several clinical trials. The treatment of choice is psoralen plus UV (PUVA) therapy, with a preference for topical PUVA because of the adverse effects associated with oral psoralen. Phototherapy is effective in both hyperkeratotic and dyshidrotic eczema.5,61–64 The recommended starting dose for UV-A phototherapy is 0.25 to 0.5 J/cm,2 with progressive increments of 0.25J/cm2 per session (3 a week).65 Treatment can fail in smokers, particularly if they have dyshidrotic eczema.66 Van Coevorden et al.67 demonstrated the effectiveness of oral PUVA with a portable tanning unit at home and proposed that it could be a good solution for patients with travel or work-related difficulties.

UV-A1 irradiation has also produced good results in dyshidrotic hand eczema, in which it exhibited a similar efficacy to PUVA but a better safety profile. Its effectiveness in other types of chronic hand eczema, however, has not been demonstrated.68–70

UV-B phototherapy has also proven effective against hand eczema,71–74 although it has not been compared with PUVA. In a randomized study of 35 patients, Rosen et al.74 demonstrated that PUVA was superior to UV-B therapy, and Simon et al.73 reported similar results in 13 patients treated with topical PUVA bath therapy or UV-B. Sjövall et al.75 proposed combining whole body UV-B irradiation with additional irradiation of the hands as a more effective option than local UV-B treatment.

Systemic TreatmentsSystemic treatments are indicated for refractory chronic hand eczema, i.e., eczema that persists after proper adherence to 8 weeks of topical treatment. It is important not to delay the introduction of oral treatment to avoid polysensitizations and improve the patient's quality of life. Most of the systemic treatments used in chronic hand eczema have not been investigated in randomized clinical trials and are therefore prescribed off-label. The only treatments approved to date are alitretinoin and, in the case of chronic hand eczema, ciclosporin.5,8,76

AlitretinoinAlitretinoin is a vitamin A receptor agonist with immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects.77 The phase III clinical study BACH (Benefit of Alitretinoin in Chronic Hand Eczema) is the largest trial conducted to date in hand eczema, earning it a level of evidence of 1b (individualized randomized controlled trial with a narrow confidence interval). It involved 1032 patients and demonstrated complete or almost complete clearance of eczema in 48% and 25% of patients treated with alitretinoin 30mg and 10mg, respectively, for 24 weeks.78 Response rates were higher in patients with hyperkeratotic hand eczema (49%) or pulpitis (44%) than in those with vesicular eczema (33%). The median time to relapse was 5.5 to 6.2 months.78 Although there is limited experience with alitretinoin, its effectiveness and safety have been corroborated in observational studies based on clinical practice.79–84 Another study showed that alitretinoin results in improved quality of life after 1 and 3 months of treatment.85

Alitretinoin is well tolerated and its adverse effects are dose-dependent. The most frequent adverse effect is headache, followed by flushing, mucocutaneous events, hyperlipidemia, and decreased thyroxine and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels.78 Alitretinoin is teratogenic and must therefore not be used in pregnancy or in women of child-bearing age who do not use adequate contraceptive methods.86

The starting dose is 30mg/d, which should be reduced to 10mg/d if adverse effects appear. Treatment should be discontinued once the eczema clears or if the eczema does not improve after 24 weeks or is still severe after 12 weeks.87 Nevertheless, it has been shown that continuing treatment for an additional 24 weeks in patients who do not clearly respond to treatment after an initial 24-week course may be beneficial and that good tolerance is maintained.88 Likewise, 80% of patients who relapsed after a good initial response responded well to a second cycle of alitretinoin 30mg/d, and therefore intermittent treatment with alitretinoin would appear to be a suitable option for long-term management of chronic hand eczema.89

AcitretinTwo studies have shown acitretin to be effective in hyperkeratotic hand eczema (level of evidence 2b). The first compared acitretin 30mg/d with placebo in 29 patients and reported a 51% reduction in symptoms after 4 weeks of treatment.90 The second study compared acitretin (25-50mg/d) with a betamethasone/salicylic acid ointment in 42 patients and observed improvements after 30 days of treatment with acitretin, with improvements persisting for 5 months after suspension of treatment.91

Systemic CorticosteroidsOral corticosteroids are effective in hand eczema flares. The usual dose is 0.5 to 1mg/kg/d of prednisone or equivalent. However, corticosteroids are not recommended for maintenance therapy because of their adverse effects, the risk of a rebound effect after stopping treatment, and a lack of clinical trials.8 Their use is supported by an evidence level of 1c due to their widespread use in clinical practice.

CiclosporinCiclosporin is an effective immunosuppressant in skin diseases such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. Although its use in hand eczema has been investigated by very few studies,92–96 it appears to be an effective treatment, as demonstrated by Granlund and coworkers in 3 studies comparing it with a topical corticosteroid (level of evidence 2b). The first study was a double-blind randomized clinical trial in which 41 patients with refractory chronic hand eczema were assigned to treatment with either topical betamethasone dipropionate or ciclosporin 3mg/kg/d for 6 weeks; both treatments resulted in improvements, with no significant differences observed between the groups.94 The second study showed a correlation between clinical improvement and improved quality of life,95 and the third study, published a year later, showed that most patients had maintained their initial response without the need for other treatment.96 The results of the 3 studies suggest that ciclosporin is effective in chronic hand eczema and that long-term remission is possible, despite the relatively short treatment period.96 Nevertheless, there is no scientific evidence on what types of eczema respond better, or on optimal doses or treatment durations.

Ciclosporin is indicated for flares (i.e., for relatively short periods of time) due to the risk of adverse effects in the long term. The recommended starting dose is 2.5 to 5mg/kg/d. This minimum therapeutic dose should be maintained for 6 months and subsequently tapered off over approximately 3 months. Treatment should be discontinued if there is no response to maximum doses or after a treatment period of 8 weeks.8,97

Other ImmunosuppressantsMethotrexate was effective in 5 patients with recalcitrant palmoplantar pompholyx at a dose of 15 to 22.5mg/wk, allowing oral corticosteroids to be reduced or eliminated.98 Mycophenolate mofetil at a dose of 3g/d for 12 months, in turn, produced good results in a patient with recurrent dyshidrotic eczema.99 These immunosuppressants are supported by a level of evidence of 4.

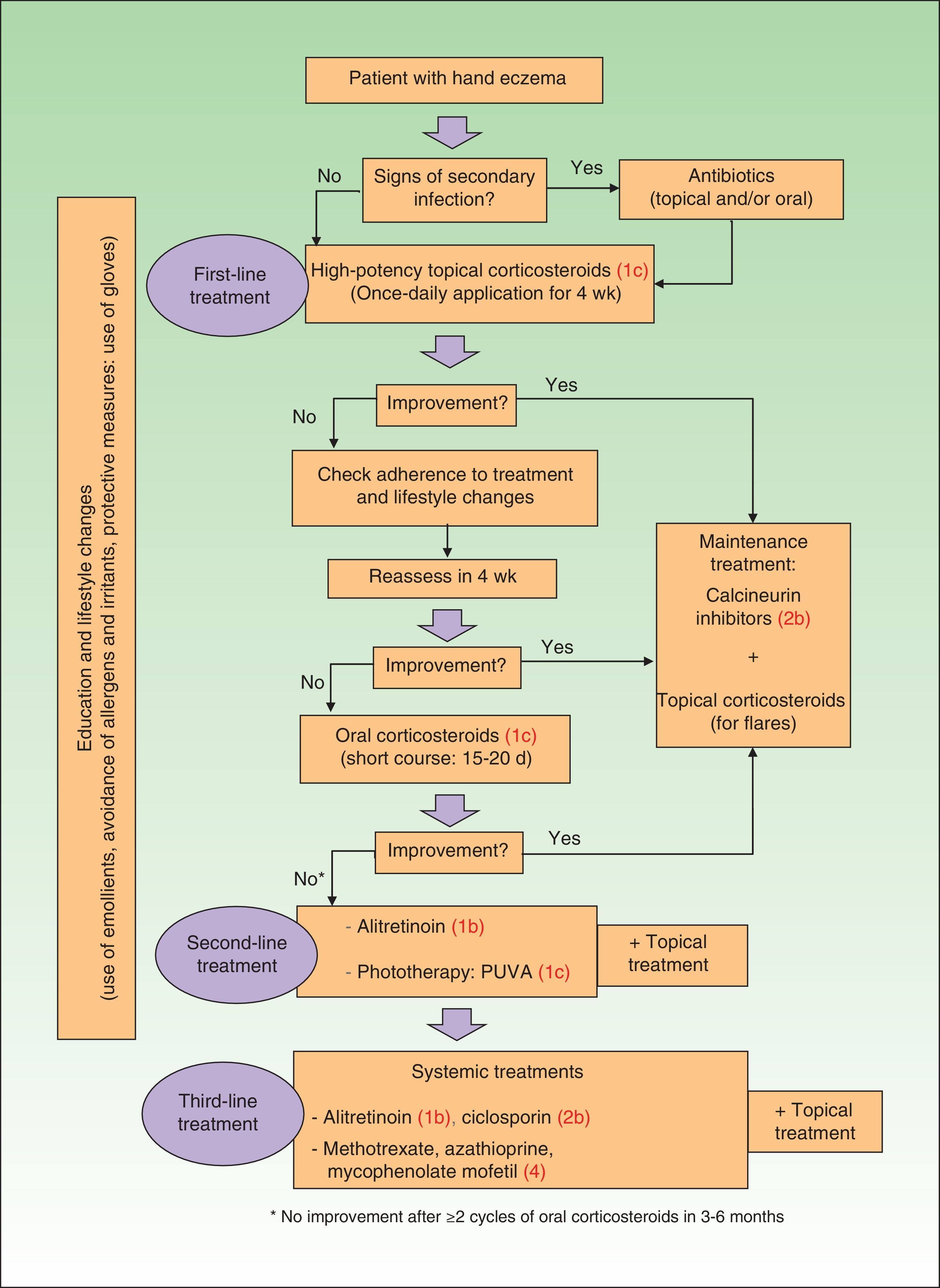

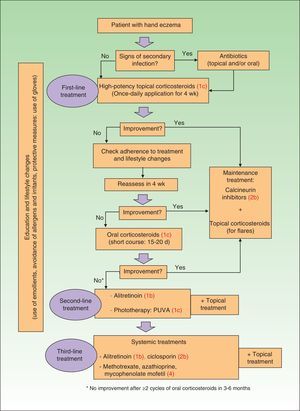

Treatment algorithmThe most recent treatment algorithms are those proposed by Diepgen et al.8 (Germany, 2009), English et al.5 (United Kingdom, 2009), and Menné et al.7 (Denmark, 2011). They all recommend topical corticosteroids, combined with protective measures and emollients, as the first line of treatment. There is a lack of consensus, however, on what should be done when this first line of treatment fails. The Danish guidelines propose any of the systemic treatments as a second line of therapy, whereas the UK guidelines recommend phototherapy, ciclosporin, azathioprine, or alitretinoin as second-line treatments and methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil as third-line treatments. They also indicate that rapid control can be achieved with ciclosporin or oral corticosteroids. The German guidelines, in turn, distinguish between a second-line of treatment (for moderate hand eczema) that includes phototherapy and alitretinoin and a third line of treatment (for severe hand eczema) that includes the other systemic treatments. The treatment algorithm we propose (Fig. 1) is based on these three guidelines and a review of the literature.

Treatment algorithm for chronic hand eczema. Levels of evidence based on the grading system proposed by the Oxford Centre for Evidence-based Medicine are shown in parentheses.40 PUVA indicates psoralen plus UV-A.

- •

Hand eczema that lasts for more than 3 months or that recurs at least twice a year despite adequate treatment and adherence should be considered chronic hand eczema.

- •

Initial management steps should include a detailed clinical history, physical examination, and patch tests.

- •

Patients should be informed about their disease, about the need to avoid irritants and allergens, and about the importance of protection measures.

- •

The first line of treatment should be topical corticosteroids administered for 4 weeks.

- •

Treatment adherence should be checked if initial treatment response is poor.

- •

If necessary, calcineurin inhibitors can be added to reduce the need for corticosteroids.

- •

Due to the lack of sufficient evidence, systemic treatments should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

- •

PUVA therapy can be considered as a second-line option when topical corticosteroids fail. Although its effectiveness is limited, it is relatively safe.

- •

Alitretinoin, a new drug approved for the treatment of chronic hand eczema, can also be considered a second-line option as it has shown good response rates in clinical trials and observational studies.

- •

Acitretin can be contemplated in hyperkeratotic hand eczema.

- •

Short courses of oral corticosteroids are useful for achieving rapid control of symptoms.

- •

Ciclosporin, azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil can all be considered third-line treatments.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: de León FJ, Berbegal L, Silvestre JF. Abordaje terapéutico en el eczema crónico de manos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106:533–544.