The interferons comprise a family of proteins belonging to the cytokines involved in regulation of the immune response. They exert antiviral, antineoplastic, antiangiogenic, and immunomodulating effects.1 High-dose interferon alfa is the only treatment to date that has been shown to improve disease-free survival in patients with advanced melanoma in randomized prospective trials.2 Its side effects are generally dose-dependent. The most common manifestations are flu-like symptoms with fever, fatigue, joint and muscle pain, and chills; increased transaminase levels and hypothyroidism are also common. Cutaneous adverse effects are observed in 5%–25% of cases,2,3 the main ones being hair loss, pruritus, acne, eosinophilic folliculitis, lichenoid eruptions, xerosis, white atrophy, ulcers, vasculitis, cutaneous necrosis, chronic pigmented purpura, panniculitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, linear immunoglobulin A dermatosis, pemphigus, urticaria, fixed drug eruption, taste disorders, exanthema, and—albeit rarely—vitiligo, alopecia areata, and other autoimmune processes.

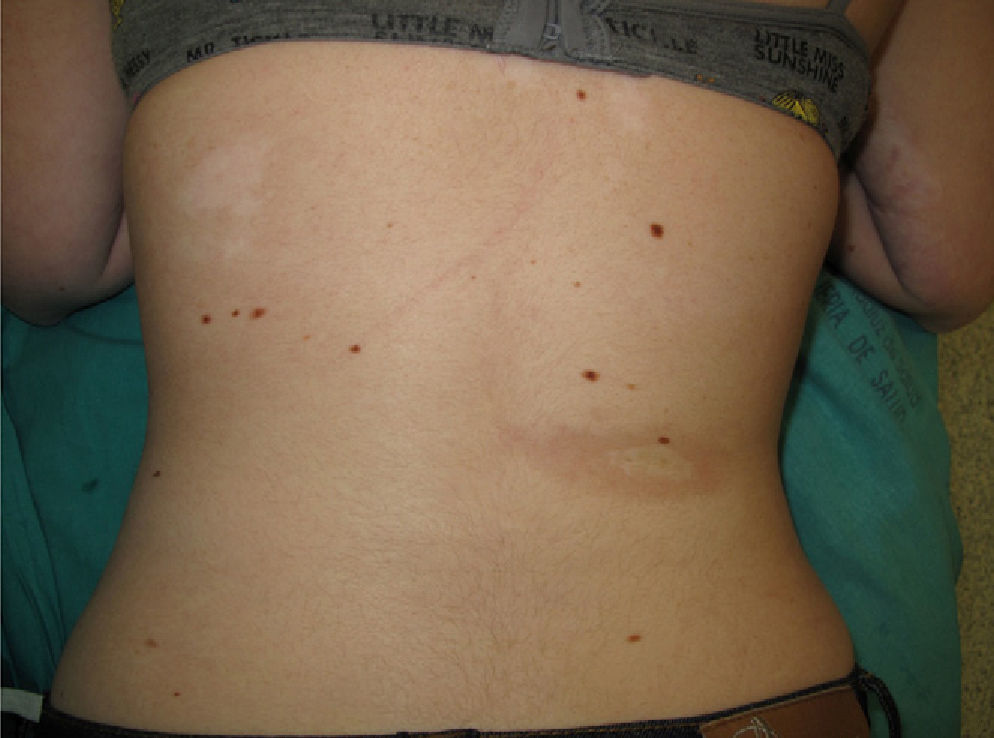

We present the case of a 20-year-old woman with no personal or family history of interest who, after removal of a melanoma (Breslow depth of 0.5mm, Clark level II, no ulceration or areas of regression) below the right clavicle, presented local recurrence (in-transit metastasis) in the form of a rapidly growing nodule, which was removed. A sentinel lymph node biopsy of the right axilla was negative. The patient received interferon alfa-2b (Kirkwood regimen) for 1 year. Shortly before finishing therapy, she presented large achromic macules on the upper third of the trunk (consistent with vitiligo) and a hard plaque with hypochromic infiltrate in the center and brownish margins on the lower back (clinically and histopathologically consistent with morphea). The laboratory workup revealed antinuclear antibodies (titer 1/160) associated with a homogeneous nucleolar pattern. Analysis of the thyroid axis was unremarkable (Figs. 1 and 2).

Simultaneous appearance of vitiligo and melanoma, irrespective of whether this occurs after treatment with interferon or not, is unusual yet widely documented. In the absence of treatment with interferon, the incidence of vitiligo and melanoma is lower than 5%, and that of vitiligo in the general population is as low as 3%. Consequently, the association between the two is not considered significant. By contrast, vitiligo affects up to 20% of patients treated with interferon.4

Morphea and sclerodermiform conditions are less frequent than vitiligo in patients treated with interferon. There have also been reports of cases in patients receiving pegylated interferon alfa combined with ribavirin for treatment of hepatitis C infection.

The simultaneous presence of vitiligo and morphea in patients with melanoma is very unusual. We only found 2 articles describing this association, and neither states the immunotherapy received or the clinical repercussions.5,6

Therefore, the association between vitiligo and interferon remains unclear. Some authors claim that it indicates a favorable prognosis, whereas others reject this theory. What does seem to be true is that patients who present autoimmune manifestations such as vitiligo and morphea after treatment with interferon are considered likely to achieve a good response, defined as increased disease-free survival.7,8

In the last 5 years, we have treated 408 patients with melanoma at Hospital Carlos Haya in Malaga, Spain. Of the 35 who received interferon, 2 developed vitiligo. The first involved a 40-year-old patient who died as a consequence of melanoma 3 years after diagnosis; the second was a 60-year-old patient who remains disease-free 6 years after treatment with interferon. Therefore, our experience does not enable us to corroborate or refute the favorable outcome of patients with vitiligo accompanied by melanoma treated with interferon.

Please cite this article as: Martínez-García S, et al. Fenómenos autoinmunes cutáneos del interferón (vitíligo-morfea). Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:250–51.