Infantile hemangiomas are frequent, benign endothelial tumors that express the marker GLUT1.1 The diagnosis is generally clinical, based on morphology and a clinical course characterized by a phase of rapid postnatal proliferation followed by a slow spontaneous involution.2,3 In some cases, when growth is minimal, these tumors are referred to as minimal growth hemangiomas, arrested growth hemangiomas, or abortive hemangiomas (AHs).4–7

Our aim was to retrospectively evaluate the clinical and histologic characteristics of AH. We examined the database and photo archives of the dermatology department at our hospital for the period of January 2006 to June 2010. Cases of infantile hemangioma in which the proliferative component of the tumor accounted for less than 25% of the total surface were selected for the review.

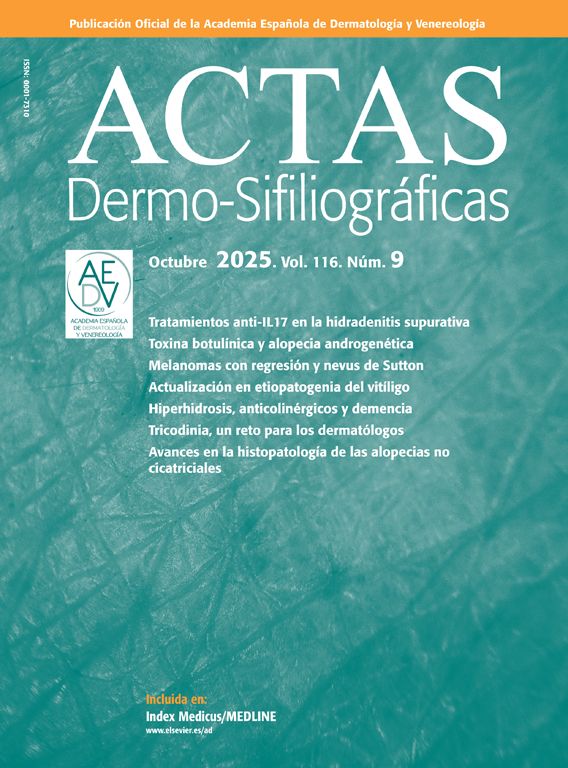

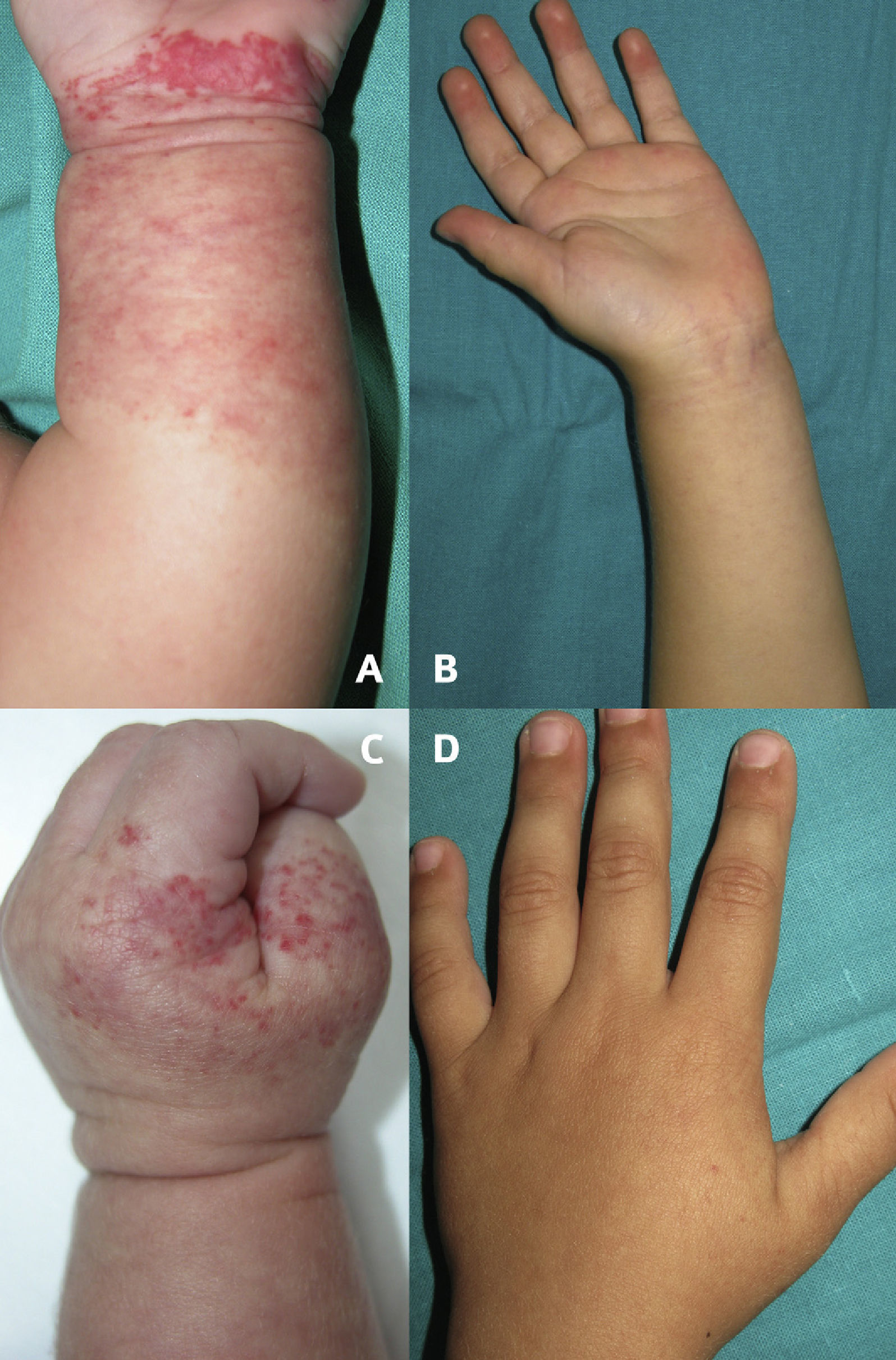

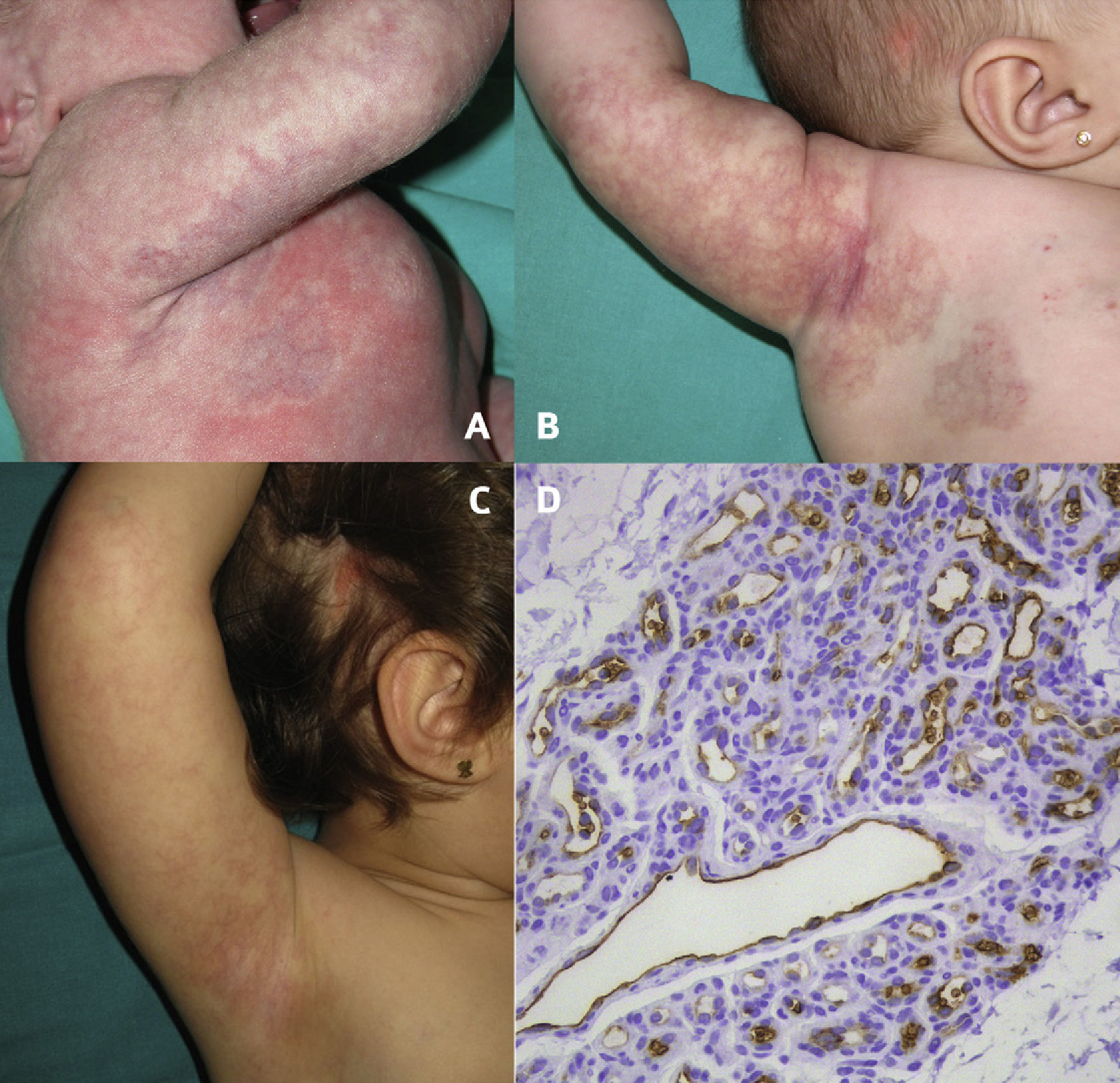

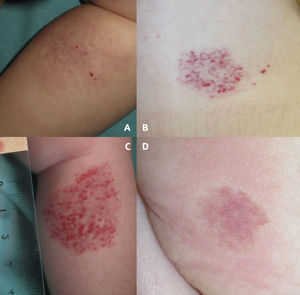

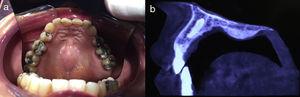

Eighteen cases of AH were identified, but 4 were eliminated because of lack of data. The remaining 14 cases affected 13 patients with a female to male ratio of 3:1 (10 girls and 3 boys). All infants were born full term (time of gestation>38 weeks) with a weight greater than 2.760g (mean weight 3.260g). During gestation, 2 mothers presented with urinary infection and 1 showed signs of preeclampsia. In 3 cases, a history of classic infantile hemangioma in a sibling was reported. The age of the infants at first consultation ranged between 1 day and 6 months (mean: 2.5 months, median: 3 months). Follow-up was carried out until 7 to 48 months of age. AH was present at birth in 71% of cases and appeared in the first 2 weeks of life in 29% of cases. Sixty-four percent of the tumors were located on the lower half of the body (face: 0; scalp: 1; upper limbs: 4; trunk: 4; lower limbs: 8). Cases were classified as focal AH (42%), partially segmental AH (29%), and segmental AH (29%). The common characteristic in 100% of cases was telangiectasias on normal or reddish skin (with a reticular distribution in 75% of the segmental tumors). Areas of pallor were seen in 50% of AHs and congenital bruiselike lesions were observed in 14% of cases. Proliferation was minimal and took the form of predominantly peripheral reddish papules in 64% of AHs and a few red spots in 22%; no growth was observed in 14% of cases (Figs. 1–3). Fading of the lesions was evident in 86% of cases, starting between 8 and 12 months of age (Figs. 1 and 2). In 2 cases in which the lesion showed no signs of involution, the final follow-up visit was made at 7 months of age. One segmental AH located in the groin ulcerated (7%). One girl presented with 2 AHs simultaneously. Another infant developed 1 classic infantile hemangioma and 1 AH. The 5 arrested growth tumors that were biopsied were positive for the marker GLUT1 (Fig. 2D). Minor developmental anomalies were detected in 50% of patients (syndactyly, sacral dimple [2 cases], nevus sebaceus on the scalp [Fig. 2C], preauricular tags, conjunctival abnormalities, hyperpigmented nevus, cleft lip, and transient pseudocoarctation of the aorta).

Abortive segmental hemangioma and nevus sebaceus on the scalp. Bruiselike segmental lesion with areas of pallor around and inside the lesion 48hours after birth (A), fine telangiectasis on pink patches with a reticular appearance and a small number of dot-like papules at 4 months of age (B), and fading of the hemangioma at 2.5 years of age (C). GLUT1 expression in both the swollen endothelial cells enclosing the small lumina and the flat endothelial cells of dilated capillaries, staining with GLUT1, ×200 (D).

Clinical images of abortive hemangiomas. Pink reticular lesion located on the leg with fine telangiectasis and 4 small red papules on the surface (A). Congenital telangiectasias in normal skin with erythematous papules that appeared after birth predominantly in the peripheral areas of the lesion. Note the pallor around the lesion (B). Central and peripheral proliferation in 25% of the surface area of an erythematous lesion (C). Pale halo surrounding a pink telangiectatic lesion on the buttock (D).

Classic infantile hemangioma is a GLUT1-positive tumor characterized by a rapid postnatal growth phase that is followed by a slow involution phase. Incidence is higher in premature infants and in the female sex, with the ratio of girls to boys ranging from 1.5:1 to 3.5:1. These tumors occur predominantly on the head and neck (60%), with focal hemangiomas appearing more frequently than segmental ones. The risk of ulceration has been estimated at 15%.3,7 In our case series the female to male ratio (3:1) was within the range reported in the literature and the lesions were predominantly focal or partially segmental. Most of the hemangiomas showed signs of regression. Histologic examinations, when performed, revealed GLUT1 expression. Postnatal growth of AHs was minimal and there were no premature infants in the group studied. Only 1 tumor was located on the head, and only 1 lesion, located in the groin, ulcerated (7%).

Few studies have described this type of arrested growth infantile hemangioma and proposed a differential diagnosis with capillary malformations, noninvoluting congenital hemangiomas, or other vascular anomalies. Corella et al.5 demonstrated that AH is a true form of hemangioma through histologic findings and GLUT1 expression. It has recently been suggested that dermatoscopy may be useful for diagnosis.6 In a retrospective study involving 47 patients, Suh and Frieden7 indicated that AHs have a particular clinical appearance, occur more frequently on the lower body, and do not predict the proliferative potential of any other hemangiomas present. Our findings in these 14 cases of AH are consistent with their conclusions; however, 3 of the 4 segmental hemangiomas in our study presented on the upper half of the body. When compared with the cases reviewed in the Suh and Frieden study, our patients were first seen at an earlier age and were monitored more closely for longer periods, factors that may explain the higher rates of growth and regression in our series.

One notable difference is that our case series involved a high frequency of minor developmental anomalies (50%), many of which were located anatomically far from the hemangioma. The present study is limited because of the small number of patients and because it is retrospective. At present, the etiology and pathogenesis of hemangiomas are not fully understood8 and more studies are needed before ruling out an etiopathogenic relationship between developmental anomalies and these tumors. Cases of AH associated with urogenital, anorectal, and cardiac anomalies as well as deep recalcitrant ulcers have been described as reticular infantile hemangiomas.9,10 One of the patients in the Suh and Frieden7 study presented with occult spinal dysraphism.

Larger clinical studies are needed to establish the true incidence of AH, confirm the predominance of these lesions on the lower half of the body, determine the risk of other developmental anomalies in these patients, and define the role of dermatoscopy as a diagnostic tool.

Please cite this article as: Martín-Santiago A, et al. Hemangiomas abortivos o mínimamente proliferativos. Revisión de 14 casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:246–50.