A 51-year-old man with a history of morbid obesity and smoking, who reported having recently taken medication, visited the emergency department with a highly pruritic rash that had appeared 2 months earlier and had spread to practically the entire body area. Physical examination revealed erythroderma consisting of the convergence of multiple erythematous-violaceous papules, some with a lichenoid sheen, accompanied by palmoplantar keratoderma (Fig. 1). The facial area was spared, together with some areas of skin on the lower part of the abdomen. Several fingernails showed trachyonychia and onychorrhexis. No abnormalities were observed in the oral or genital mucosa. The patient’s general condition was good, with no symptoms in other organs or systems, no enlarged lymph nodes, and no fever. Due to the intense pruritus, the patient had received treatment in primary care with 5% topical permethrin and methylprednisolone at low doses, with no improvement. No other family members suffered from pruritus.

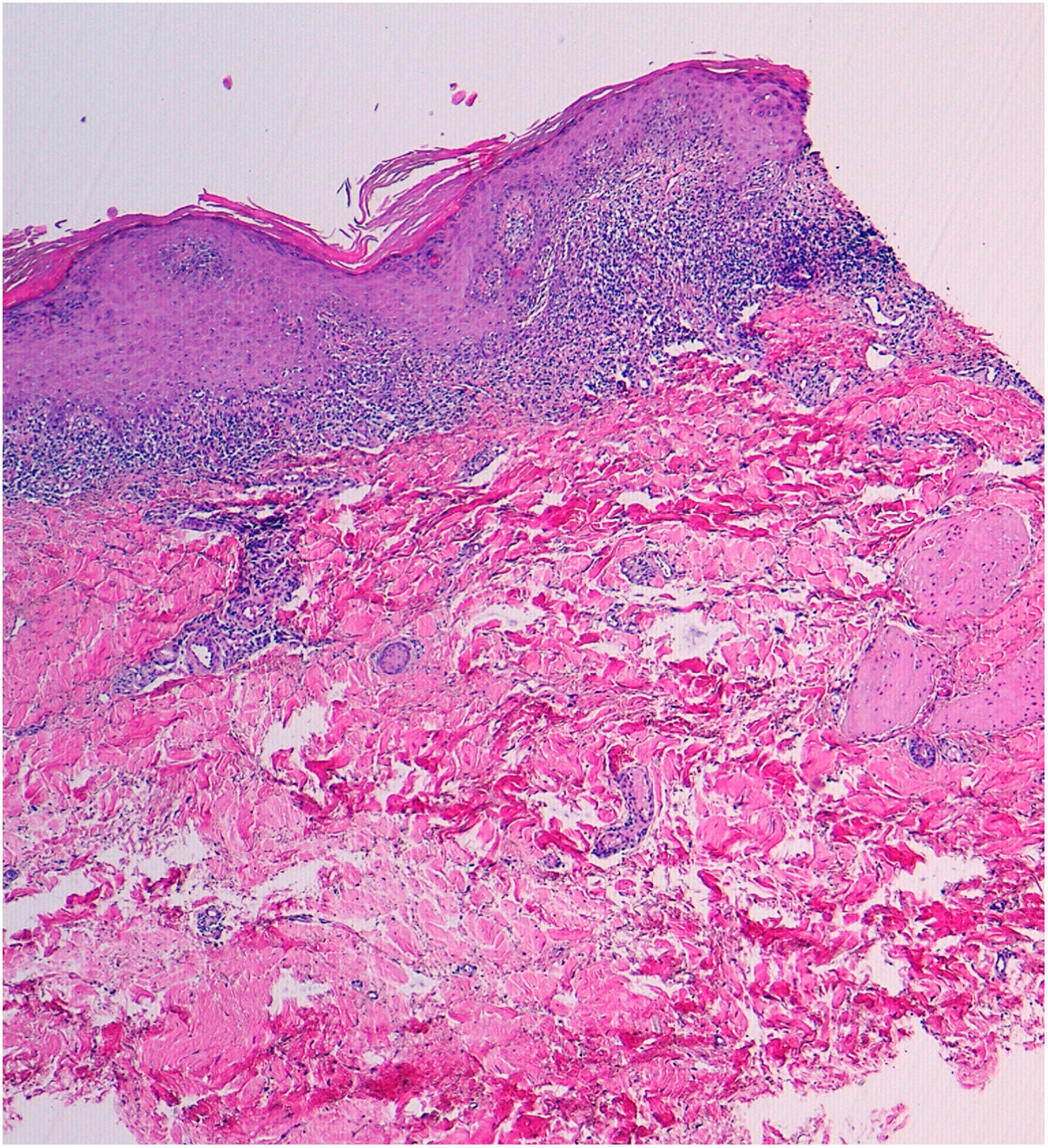

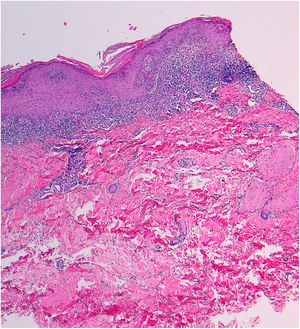

A punch biopsy was performed, and histology revealed intense lichenoid interface dermatitis, with lymphocyte infiltrate with no eosinophils or plasma cells, with apoptotic Civatte bodies in the basement layer and absence of parakeratosis (Fig. 2). A general analysis was ordered (blood count, biochemistry, renal function, liver function, and lipid profile) with normal results. Serology for HVB, HVC, HIV, and syphilis, and antinuclear antibody determination, anti-SSA-Ro, and anti-SSB-La were negative.

Given the results of the general analysis and while waiting for the other additional tests, treatment with cyclosporin (400 mg/24 h) was instated, as its use was not contraindicated and covered other potential causes of erythroderma, such as atopic dermatitis and psoriasis. After a week, the patient reported notable improvement of the lesions, with complete disappearance of the pruritus. A month later, only residual hyperpigmentation was observable (Fig. 3). It was possible to suspend medication and the patient remained without signs of recurrence after 6 months of follow-up.

Because the patient stated that he had not previously taken or applied drugs or been exposed to toxins, and based on the clinical and pathology findings, a diagnosis was made of erythrodermic lichen planus, a very rare variety of both lichen planus and erythroderma.

Lichen planus or an extensive lichenoid drug reaction must be taken into account in the differential diagnosis of erythroderma.1–3 The presence of lesions with a lichenoid sheen in the habitual locations (wrists and/or ankles) and the blue-violaceous color can provide clinical guidance that the erythroderma is due to a lichen planus.4

The distinction between an extensive lichenoid drug reaction (ELDR) and an erythrodermic lichen planus (ELP) may be difficult to establish. ELDR is secondary to the use of drugs and it is therefore important when taking the patient’s history to inquire about previous ingested or topical drugs or other substances. These signs and symptoms appear mainly on the torso, do not usually involve the ankles and wrists (at least initially), and may present an eczematous or psoriasiform appearance, with a photosensitive or symmetrical pattern. Histology may reveal eosinophils and plasma cells, which are much less common in cases of ELP, together with parakeratosis and cytoid bodies in the upper layers of the epidermis, which are also rare in ELP. ELDR does not usually present Wickham striae when examined using dermoscopy. ELP, however, tends to initially appear in the typical areas, is not distributed in areas exposed to sunlight, and more frequently involves the mucosa. Lichenoid reactions have been reported after use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antihypertensive drugs (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors), antifungal agents (ketoconazole), antiretroviral drugs, antibiotics (tetracyclines), beta-blockers (propanolol), antimalarials, cytostatic drugs, tuberculostatic agents (ethambutol), diuretics (thiazides), anticonvulsives (carbamazepine), gold and lithium salts, heavy metals, hypouricemic agents (alopurinol), hypoglycemic agents (sulfonylureas), thyrosine kinase inhibitors, anti-TNF drugs, and others (methyldopa, penicillamine, diltiazem, chlorpromazine, etc).5

In the case of our patient, no drugs prior to the rash were identified. Moreover, the response to cyclosporin was excellent, with no relapse when the drug was suspended. This drug has been used sporadically and successfully in lichen planus6 and its use may be considered to achieve rapid control of symptoms when lesions are very extensive.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: P.J. Gómez Arias, F. Leiva Cepas, M. Galán Gutiérrez, Vélez García-Nieto AJ. Liquen plano eritrodérmico. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021;112:565–567.