“Pseudomelanocytic nests,” a more precise term than the commonly used “pseudonests,” are described in the literature as a diagnostic pitfall for pathologists.1 They are nests that stain with some melanocytic markers, but on further investigation, a melanocytic etiology is discordant with the clinical picture and further immunohistochemistry. Pseudonests have been described in lesions ultimately diagnosed as discoid lupus erythematosus, lichenoid phototoxic reactions, lichen planus pigmentosus, fixed drug eruptions, and lichen planus.1–4 They create a diagnostic pitfall when mistaken for a melanocytic process, especially if using a single stain, such as Melanoma Antigen Recognized by T-cells 1 (MART-1) or, a related stain, Melan-A.2 The literature cautions MART-1/Melan-A positivity can be misleading, because MART-1/Melan-A's cytoplasmic antigen in the melanosome can be transferred between cells during inflammation.1,3,5

We present a patient thought to have a malignant melanoma in situ (MMIS) with marked regression upon initial biopsy, but was more consistent with lichen striatus upon subsequent biopsy and clinical correlation.

Case ReportA 32-year-old male presented with a changing lesion on his anterior shoulder. The lesion was partially biopsied with a clinical differential diagnosis of an atypical melanocytic lesion vs Becker's nevus (Figure 1).

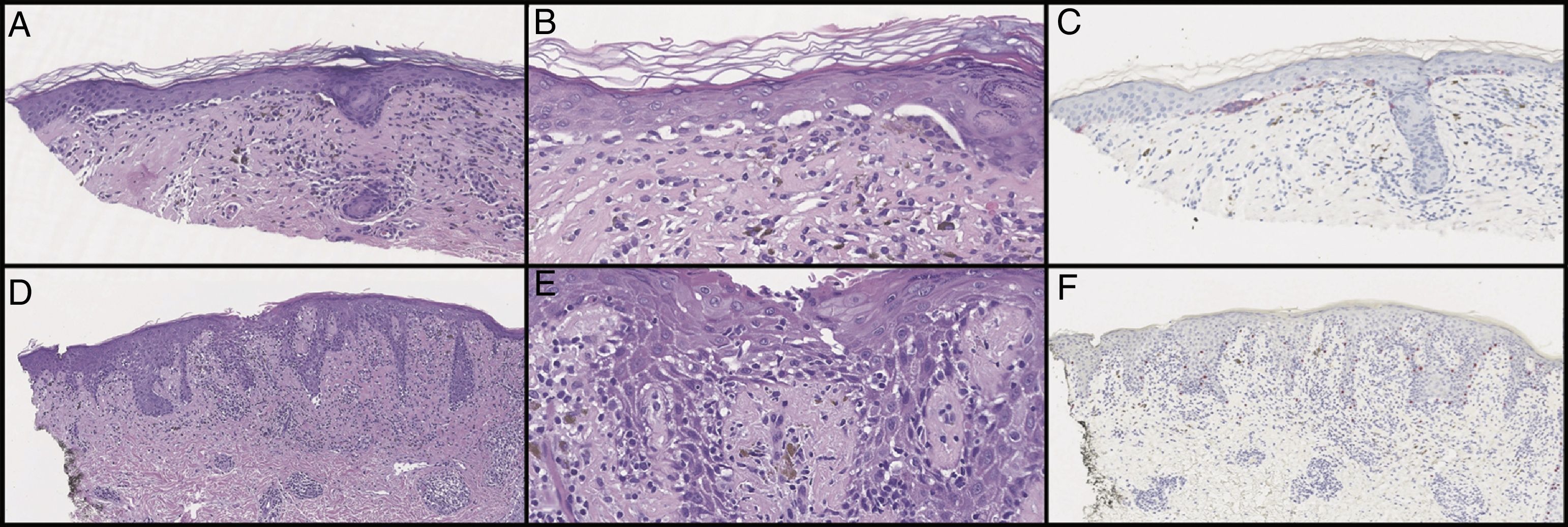

Initial histological review showed single and atypical cells at the dermoepidermal junction (Figure 2). MART-1 mildly highlighted cell aggregates (Figure 2). Atypical lentiginous junctional cells were suspicious for MMIS with marked regression. The patient was referred to oncology, who consulted the pathologist, and sampled the lesion again.

Initial biopsy showed diminished rete ridges and atypical cells in nests and as single cells with an underlying lymphohistiocytic infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) on low (A) and high (B) magnification. MART-1 showed weak staining of the lesional cells (C). Subsequent biopsies showed less nesting on H&E on low (D) and high (E) magnification and did not show a melanocytic neoplasm with SOX10 stains (F). Pankeratin and S100 were only focally positive (not pictured).

Additional samples showed fewer pseudonests, and SRY-related HMG-box Gene 10 (SOX10) did not show a melanocytic neoplasm (Figure 2). After examination of the subsequent biopsies and clinical image, the lesion was felt to represent a lichenoid process with marked pigment incontinence, most consistent with lichen striatus with melanocyte pseudonests.

DiscussionThis case highlights a diagnostic pitfall in lichenoid processes with pseudonests, for which misdiagnosis has repercussions in treatment and management. The clinical and histological findings point to a lichenoid process and are not consistent with MMIS.

After pseudonests were initially described, other studies cautioned using MART-1/Melan-A in pigmented lesions with chronic sun damage.1,3,6 Despite studies suggesting pseudonests were rare, Silva et al. cautioned against excluding it from the differential diagnosis and heeded prior warnings to use multiple stains.2

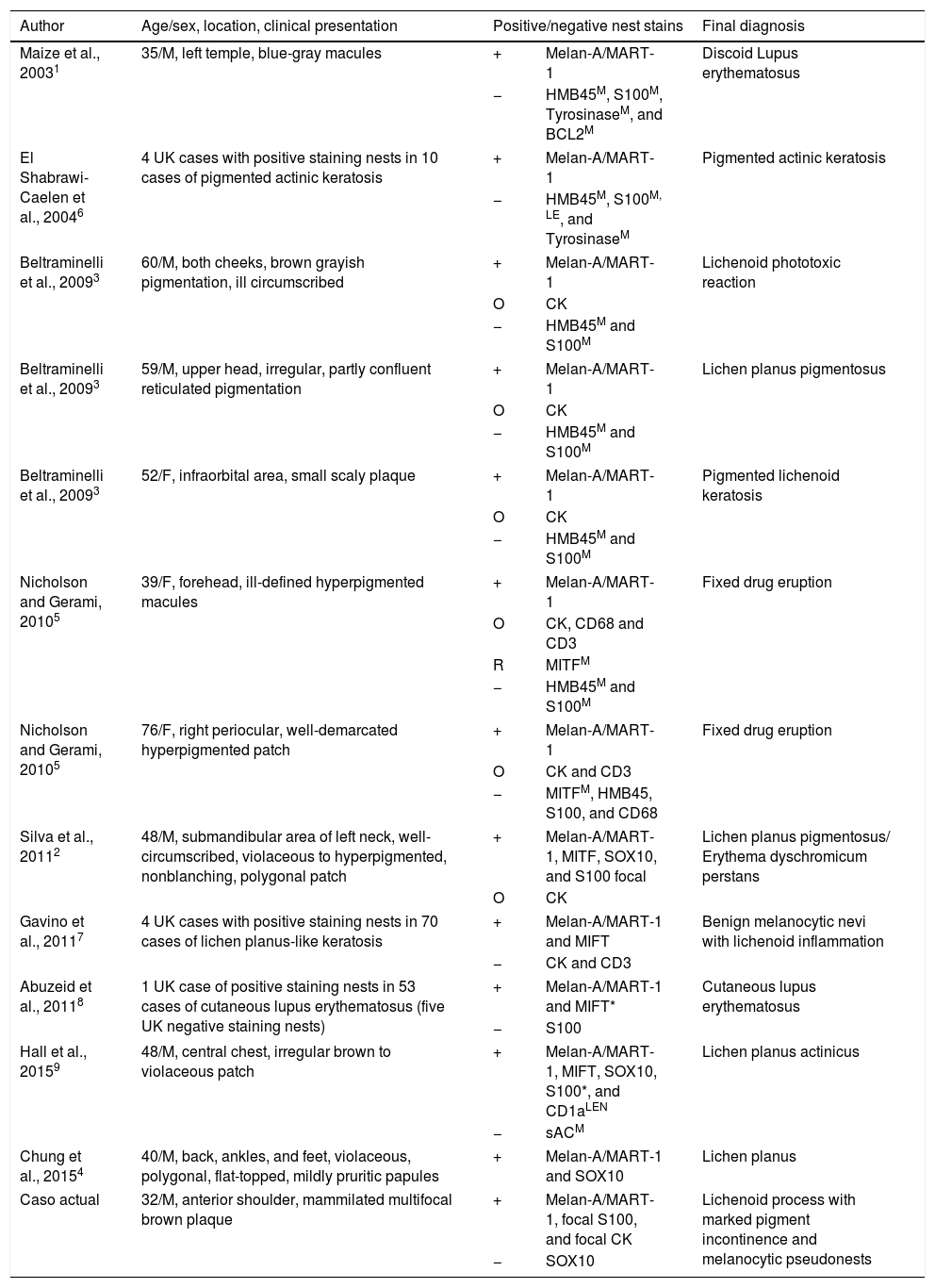

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), a nuclear epitope, and SOX10, a regulator for MITF, are more specific due to nuclear epitopes not readily transferring between cells in inflammation.5 Therefore, other studies used supplementary stains, such as SOX10 or MITF, to verify true melanocytic components with benign reorganization.2,4,7 MITF differentiated pseudonests from true melanocytic lesions after labeling cells consistently with other stains, such as S-100 or SOX10.2,5 S-100 is considered one of the most sensitive stains for melanocytic lesions and specific against pseudomelanocytic nests due to a lack of aberrant staining in the literature.8,9 Thus, MITF's efficacy was challenged after MITF positive/S-100 negative nests were found in 30 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus with lichenoid interface dermatitis.8 Authors hypothesized MITF stains similarly to MART-1/Melan-A and insisted on clinical correlation and S-100 staining when both MART-1/Melan-A and MITF are positive.8 The term “melanocytic pseudonests” was suggested for benign lesions with positive nest staining beyond MART-1/Melan-A in greater than 1-2 cells and not clinically thought to be MMIS.2 A summary of studies and nest stain positivity can be found in Table 1.

Pseudomelanocytic Nests or Melanocytic pseudonests in the Literature.

| Author | Age/sex, location, clinical presentation | Positive/negative nest stains | Final diagnosis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize et al., 20031 | 35/M, left temple, blue-gray macules | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Discoid Lupus erythematosus |

| − | HMB45M, S100M, TyrosinaseM, and BCL2M | |||

| El Shabrawi-Caelen et al., 20046 | 4 UK cases with positive staining nests in 10 cases of pigmented actinic keratosis | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Pigmented actinic keratosis |

| − | HMB45M, S100M, LE, and TyrosinaseM | |||

| Beltraminelli et al., 20093 | 60/M, both cheeks, brown grayish pigmentation, ill circumscribed | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Lichenoid phototoxic reaction |

| O | CK | |||

| − | HMB45M and S100M | |||

| Beltraminelli et al., 20093 | 59/M, upper head, irregular, partly confluent reticulated pigmentation | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Lichen planus pigmentosus |

| O | CK | |||

| − | HMB45M and S100M | |||

| Beltraminelli et al., 20093 | 52/F, infraorbital area, small scaly plaque | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Pigmented lichenoid keratosis |

| O | CK | |||

| − | HMB45M and S100M | |||

| Nicholson and Gerami, 20105 | 39/F, forehead, ill-defined hyperpigmented macules | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Fixed drug eruption |

| O | CK, CD68 and CD3 | |||

| R | MITFM | |||

| − | HMB45M and S100M | |||

| Nicholson and Gerami, 20105 | 76/F, right periocular, well-demarcated hyperpigmented patch | + | Melan-A/MART-1 | Fixed drug eruption |

| O | CK and CD3 | |||

| − | MITFM, HMB45, S100, and CD68 | |||

| Silva et al., 20112 | 48/M, submandibular area of left neck, well-circumscribed, violaceous to hyperpigmented, nonblanching, polygonal patch | + | Melan-A/MART-1, MITF, SOX10, and S100 focal | Lichen planus pigmentosus/ Erythema dyschromicum perstans |

| O | CK | |||

| Gavino et al., 20117 | 4 UK cases with positive staining nests in 70 cases of lichen planus-like keratosis | + | Melan-A/MART-1 and MIFT | Benign melanocytic nevi with lichenoid inflammation |

| − | CK and CD3 | |||

| Abuzeid et al., 20118 | 1 UK case of positive staining nests in 53 cases of cutaneous lupus erythematosus (five UK negative staining nests) | + | Melan-A/MART-1 and MIFT* | Cutaneous lupus erythematosus |

| − | S100 | |||

| Hall et al., 20159 | 48/M, central chest, irregular brown to violaceous patch | + | Melan-A/MART-1, MIFT, SOX10, S100*, and CD1aLEN | Lichen planus actinicus |

| − | sACM | |||

| Chung et al., 20154 | 40/M, back, ankles, and feet, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped, mildly pruritic papules | + | Melan-A/MART-1 and SOX10 | Lichen planus |

| Caso actual | 32/M, anterior shoulder, mammilated multifocal brown plaque | + | Melan-A/MART-1, focal S100, and focal CK | Lichenoid process with marked pigment incontinence and melanocytic pseudonests |

| − | SOX10 | |||

+: positive staining nests; −: negative staining nests; O: occasional cells in nests; R: rare cell in nests; UK: unknown; *: some cells exhibit non-staining nuclei; M: normal distribution of melanocytes at dermal-epidermal junction; LEN: Langerhans cells in epidermis and nests; LE: Langerhans cells in epidermis.

Alternative compositions of nests, such as cells or cellular debris from melanocytes, melanophages, lymphocytes, or keratinocytes, are speculated to cause the aberrant MART-1/Melan-A staining.2,7 Silva et al. hypothesized pseudonests originate during lichenoid inflammation due to either recruitment or benign reorganization of true melanocytes,2 and Hall et al. used soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC) and CD1a to differentiate S-100 and sAC positive junctional melanocytes from superficial S-100 and CD1a positive epidermal Langerhans cells.9 Other causes for discrepancies include differing staining protocols, study types, or disease processes.7

Due to the controversy, several histologic features are important when differentiating lesions beyond stains. For instance, the lack of pagetoid spread or surrounding lentiginous melanocytic proliferation makes MMIS unlikely,2 while non-staining nuclei in MITF positive nests hint to non-melanocytic origins.8 Conversely, features suggestive of atypical melanocytic lesions include an abundance of positive staining junctional nests,4 confluent non-nested melanocytes, solar elastosis, effaced rete ridges, and ‘starburst’ giant cells.10

ConclusionDermatologists’ awareness of pseudomelanocytic nests is critical in avoiding a severe diagnostic pitfall. Clinicians should be cognizant of the possibility for pseudomelanocytes if the clinical differential diagnosis includes a lichenoid process and a pathology report describes an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. In the presence of Melan-A/MART-1 positivity, panels of multiple melanocytic markers, such as S-100 and/or MITF (or SOX10), markers of keratinocytic origin, and histologic correlation with the clinical context are essential for correct diagnosis. More studies are needed to determine the true nature of pseudonests and the sensitivity/specificity of stains in evaluating pseudonests.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: McClanahan D, Choudhary S, Zahniser J, Ho J. Trampas diagnósticas: nidos seudomelanocíticos en el contexto de la inflamación liquenoide. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:321–325.