The generation of cell blocks (CB) obtained from ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration biopsies (USFNAB) is a well-established technique in breast and thyroid pathology, but is rarely used in dermatology. We reviewed CBs obtained from USFNAB of skin lesions, which were categorized as malignant skin tumors, benign skin tumors, inflammatory skin tumors or deposit skin diseases. The diagnostic yield of each category was compared to histopathology. The USFNAB of 51 skin lesions was processed into CBs. There was overall agreement between histopathology and CBs in 84.31% of cases. Diagnostic group concordance for benign, malignant as well as inflammatory and deposit skin lesions were 69.2%, 93.7% and 86.3% respectively. Cell block generation from USFNAB aspirates of skin lesions should be considered as part of the dermatologic diagnostic armamentarium. Further experience is needed to better understand for which types of dermatologic lesions it would be clearly indicated.

La generación de bloques celulares (CBs) obtenidos a partir de punción-aspiración con aguja fina guiada por ultrasonido (USFNAB), es una técnica bien establecida en patología mamaria y tiroidea, pero rara vez se utiliza en dermatología. Revisamos los CBs obtenidos por USFNAB de lesiones cutáneas, que se clasificaron como tumores cutáneos malignos, tumores cutáneos benignos, tumores cutáneos inflamatorios o enfermedades cutáneas por depósito. El rendimiento diagnóstico de cada categoría se comparó con la histopatología. La USFNAB de 51 lesiones cutáneas se procesó en CBs. Hubo concordancia global entre la histopatología y los CBs en el 84,31% de los casos. La concordancia entre histopatología y CBs para lesiones cutáneas benignas, malignas e inflamatorias y por depósito fue del 69,2, 93,7 y 86,3%, respectivamente. La generación de CBs a partir de USFNAB de lesiones cutáneas debe considerarse como parte del arsenal diagnóstico dermatológico. Se necesita más experiencia para comprender mejor para qué tipos de lesiones dermatológicas estaría claramente recomendado.

Ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsies (USFNAB) of skin lesions are not common practice in dermatology, mainly because cutaneous lesions are largely amenable to punch or excisional biopsies. However, certain lesion or patient specific circumstances make these architecture-preserving sampling strategies more complex. Fine needle aspirations (FNAs) can reach deeper areas in a more targeted way, allowing for avoidance of neurovascular structures,1 especially when under ultrasound guidance. Further, FNAs are less traumatic than punch or excisional biopsies of a same given site.1

Another reason for which FNAs are often overlooked in dermatology is that conventional processing of FNA specimens limits cytoarchitectural feature distinction or immunohistochemistry (IHC) evaluation, which hinders the diagnostic performance of this technique.2 However, cell blocks (CBs) produced from these collected cells are frequently used in cytopathology, owing to processing techniques that can concentrate obtained aspirates to generate a “pseudo-histological sample” that can also be processed for IHC. This in turn increases the diagnostic potential of USFNAB obtained material.3 Extensive applications of this processing technique in dermatology have not been reported until now, other than our initial work.4,5 We report our center's experience with the generation of CBs from USFNABs in the diagnosis of skin lesions.

Materials and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed cell blocks obtained from USFNABs in skin lesions performed in the dermatology department of Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro in collaboration with the pathology department from the same hospital from January 2019 to March 2021. Epidemiological variables such as age and sex, anatomical location and cytology and histology diagnosis after excision of the lesions were retrieved from clinical and pathology reports. This study was reviewed and approved by our Institutional Review Board. The procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

A dermatologist with specific training in the technique performed the USFNABs. Aspiration was performed with a 25-gauge needle and 20mL syringe with a pistol handle. Multidirectional withdrawal of the needle through the lesion under sonographic view yielded sufficient material for diagnosis. The same pathologist (L.N.B.) performed rapid on-site evaluation of the aspirate immediately after FNAB to assess the adequacy of sampling for diagnosis.

Smears were routinely stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa and Papanicolaou stains. Cellular blocks were produced from the obtained material by adding thrombin to the aspirate, as originally described by De Girolami.6,7 Usual paraffin inclusion and processing followed, which also allowed for immunohistochemistry staining.

ResultsA total of 51 dermatologic lesions in 51 patients (30 men, 21 women, mean age 60.5+/−4 years old) were processed for CBs obtained from FNAB. Most lesions were located on limbs (22/51 43.1%) followed by the trunk (15/51 29.4%) and the head and neck (14/51; 27.4%).

Most lesions corresponded to deposit and inflammatory disorders (22 lesions, 43.1%) followed by malignant skin tumors (16 lesions, 31.3%) and benign skin tumors (13 lesions, 25.4%). Histologic diagnoses and diagnostic agreement rates with CBs are shown in Table 1.

Histopathology diagnoses from excised lesions and agreement rates after comparing cytological diagnoses with histopathology.

| Histologic diagnosis (n) | Correct cell block diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Benign skin tumors (13) | 9/13 (69.2%) |

| Pilomatrixoma (2) | 2/2 |

| Osteoma (1) | 1/1 |

| Epidermoid cyst (2) | 2/2 |

| Mucinous cyst (1) | 1/1 |

| Spindle cell lipoma (2) | 1/2 |

| Spiradenoma (1) | 0/1 |

| Schwannoma (1) | 0/1 |

| Fibrofolliculoma (1) | 0/1 |

| Poroma (1) | 1/1 |

| Lymphatic malformation (1) | 1/1 |

| Malignant skin tumors (16) | 15/16 (93.7%) |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (6) | 6/6 |

| Melanoma metastases (4) | 3/4 |

| Adenocarcinoma metastases (2) | 2/2 |

| Lung metastases (3) | 3/3 |

| Plasmacytoma (1) | 1/1 |

| Inflammatory skin diseases and other (22) | 19/22 (86.3%) |

| Scar (6) | 6/6 |

| Inflammatory lymph nodes (4) | 4/4 |

| Amyloidosis (2) | 2/2 |

| Fat necrosis (2) | 1/2 |

| Sarcoidosis (1) | 1/1 |

| Leishmaniasis (1) | 0/1 |

| Hematoma (2) | 2/2 |

| Fibromatosis (2) | 1/2 |

| Inflammatory granuloma (1) | 1/1 |

| Abscess (1) | 1/1 |

| Total=51 lesions | 43/51 (84.31%) |

In our case series, there was overall concordance of histologic and CB diagnosis in 43 of 51 cases (84.31%). Agreement was of 69.2% for benign skin lesions, 93.7% for malignant lesions and 86.3% for deposit and inflammatory skin lesions. No complications related to the technique (hematoma, infection) were reported.

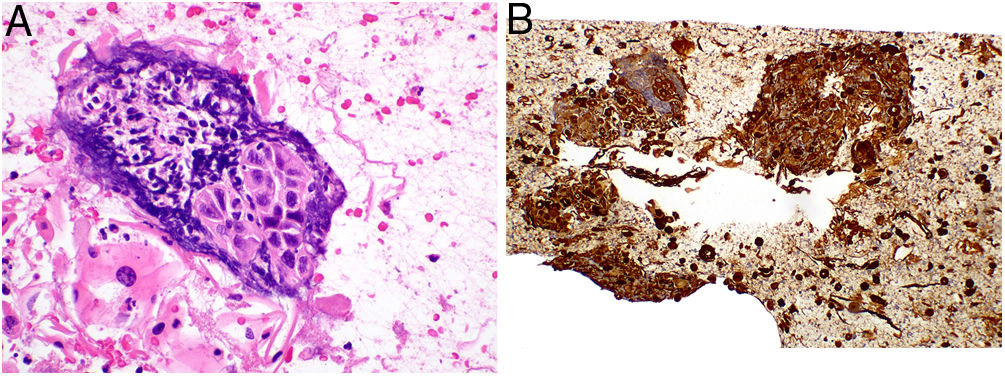

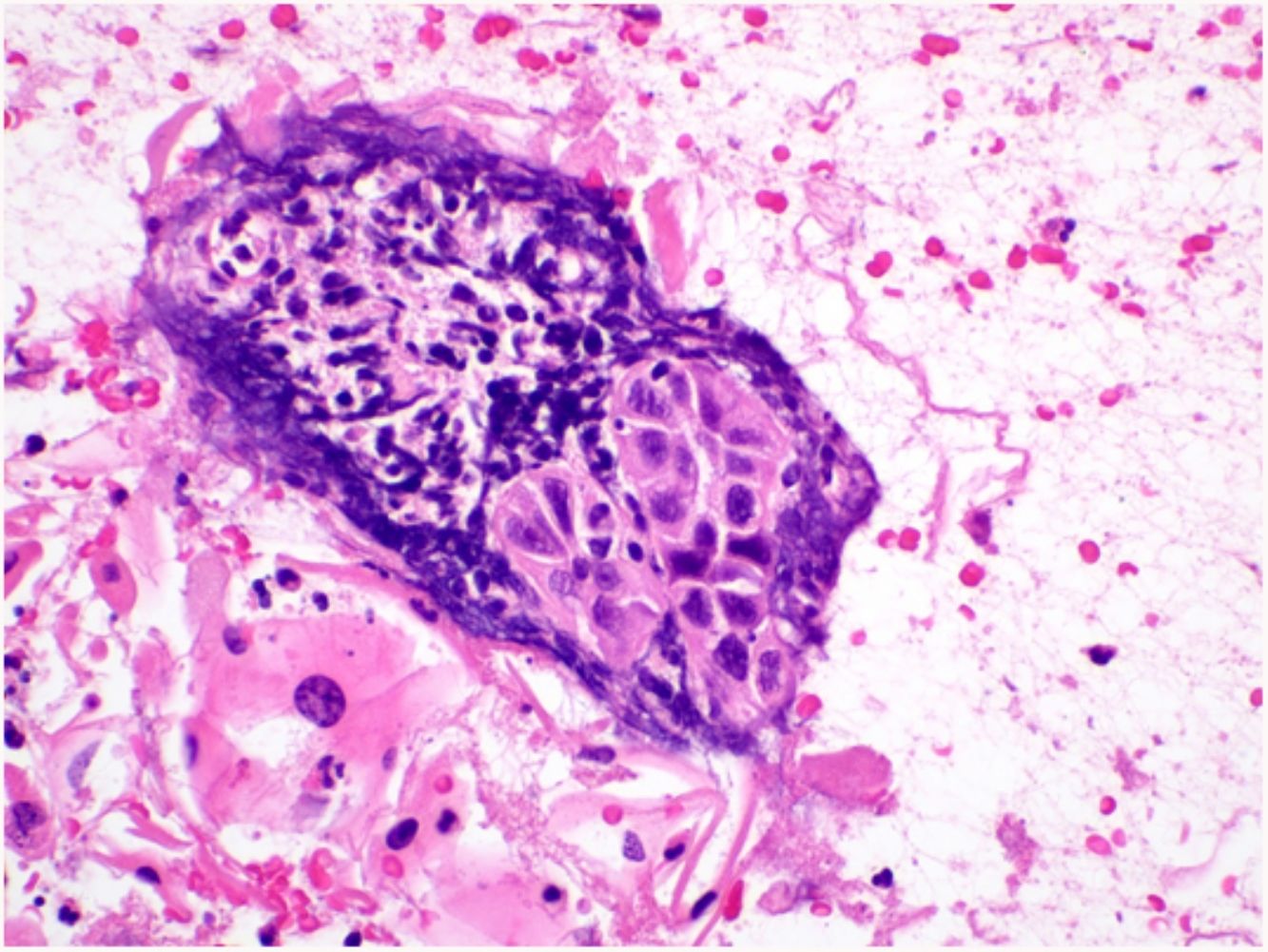

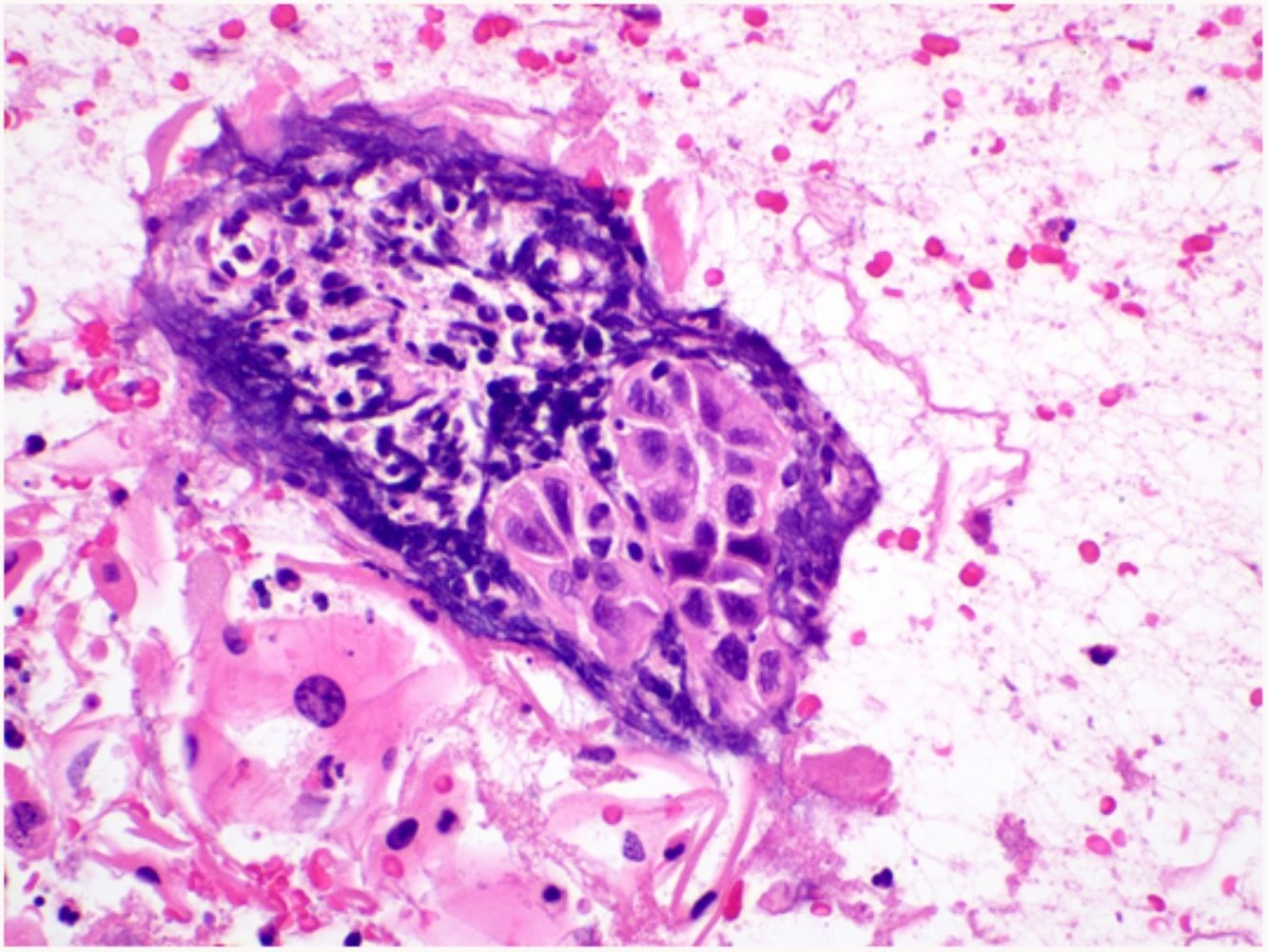

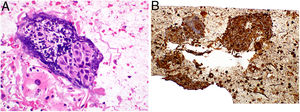

DiscussionFine needle aspiration biopsies have not been widely used in dermatology, mainly because of limitations related to the lack of histological architecture and the more restricted options of subsequent IHC and molecular biology studies. However, CB processing of FNAB material is a well-established approach in other tissues such as breast, thyroid, and effusions.6,7 This method overcomes most of the limitations of FNAB alone, making it possible to conduct IHC studies in formalin processed CBs and to use molecular biology techniques. Furthermore, the coagulation technique used in CBs creates a “pseudo architecture” that is similar to what would be seen on conventional biopsies7 (Fig. 1).

FNAs with smears have been well studied in a variety of dermatological lesions by a Spanish group,1,8–13 with reasonably good correlation between cytology and histology diagnoses. In a letter to the editor, this group emphasizes the benefits of FNAs and smears as being low cost and rapidity, noting that additional cell block generation would be more costly and time consuming, rendering the technique less appealing.14 While these statements hold true, we would like to highlight that cell blocks provide additional information and may be of interest for specific IHC or molecular studies that cannot be conducted on smears for more ambiguous lesions.

Initial experiences of FNAB in dermatology yielded a high diagnostic rate for concrete diagnosis of dermatologic diseases, but these studies did not include inflammatory or deposit diseases.15–17 In these previous studies, FNAB was performed using a blind technique. In our series, the sampling procedure is performed under US guidance, increasing the safety of FNAB as material is extracted from the lesion of interest while visually confirming the location of surrounding vasculature and nerves.18 The presence of the pathologist during the procedure is also advantageous since sufficiency of the specimen can be assessed in situ, as was the case in our study, bearing in mind that a sufficient sample is not necessarily a diagnostic sample.

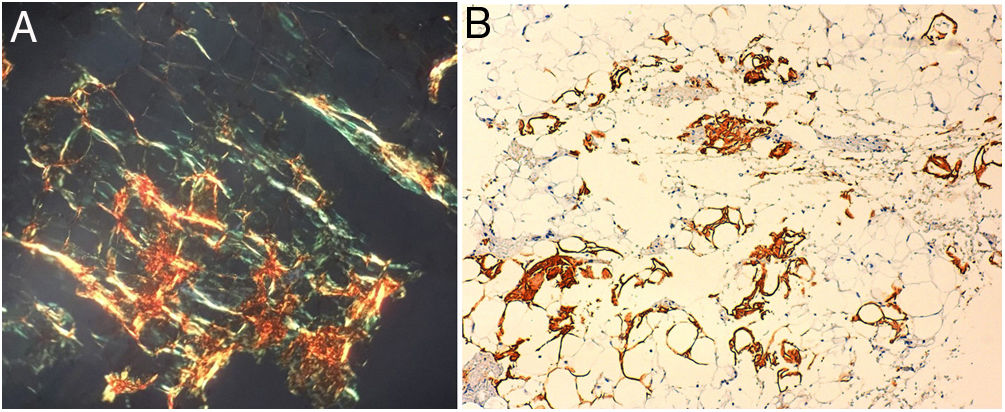

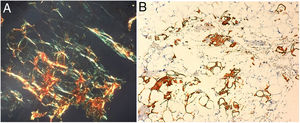

In our case series, the CBs we obtained from USFNAB were more accurate in diagnosing malignant lesions, likely due to the more specific cytological and immunohistochemical features specific to this kind of lesion.19 As for benign lesions and inflammatory or deposit lesions, the diagnostic yield was lower as their appearance is less characteristic and there are fewer pathognomonic features specific to them.16 Nevertheless, in the case of deposit diseases such as amyloidosis, FNAB allows for the sampling of a wider area which increases the probability of identification of amyloid deposits20 (Fig. 2).

Limitations of our work include the limited number of cases and the operator dependence of ultrasound-guided techniques. The ability of this approach to safely reach subcutaneous lesions that may not otherwise be accessible by punch biopsy as well as the additional testing possibilities for IHC and molecular studies in comparison to a smear are strengths of this technique and could make USFNAB cell blocks an optimal diagnostic strategy in fragile patients for who a punch biopsy could lead to increased morbidity and in whom a smear would not suffice.

ConclusionCell block generation from FNAB aspirates of skin lesions is a diagnostic technique that should be considered as part of the dermatologic diagnostic armamentarium. Collaboration between pathologists and clinicians is key to maximize the diagnostic possibilities of this approach. However, further experience is needed to better understand for which types of dermatologic lesions this minimally invasive procedure would be clearly indicated.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.