Calciphylaxis is a rare disease characterized by cutaneous ischemia and necrosis caused by mural calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels.1 This condition leads to cutaneous ulceration and eschar formation. It generally affects patients with end-stage renal failure and secondary hyperparathyroidism,1–3 and is associated with a poor prognosis, high morbidity, and high mortality rates.1–4 In recent years, cases have been reported of calciphylaxis in patients with normal kidney function and calcium–phosphate metabolism.4–7 When seen in patients without abnormalities of this sort—a rather rare occurrence—the condition is called atypical calciphylaxis.6 It has occasionally been reported in patients receiving oral anticoagulant therapy with coumarin derivatives, such as warfarin and phenprocoumon.3,4,6,7

We present the case of an 80-year-old woman who came to our hospital with purpuric skin lesions in a livedoid pattern that had appeared 2 months earlier on the back of the right leg. The lesions were associated with induration and intense local pain. Several weeks after the onset of the first symptoms, the patient noticed the appearance of an ulcer, which was quickly covered by necrotic eschar. Similar intensely painful skin lesions began to appear on the left leg at the same time.

Relevant aspects of her medical history included diabetes mellitus, bronchial asthma, arterial hypertension, and atrial fibrillation. Current medication included acenocoumarol (which she had been taking for 1 year), acetaminophen, omeprazole, diltiazem, metformin, tiotropium bromide, and a formoterol–budesonide combination.

Dermatological examination revealed a well-defined and extremely painful ulcer on the back of the patient's left leg (Fig. 1). The lesion was covered with eschar and surrounded by a racemose erythematous-violaceous plaque. Livedo reticularis was observed on the back of both legs. The skin lesions and the underlying area were indurated on palpation. The patient's right leg had similar lesions, but without necrotic eschar. The physical examination was otherwise normal.

Testing revealed normal levels of urea, creatinine, parathyroid hormone, calcium, serum phosphate, protein C, and protein S. The patient tested negative for cryoglobulins and for antinuclear and anticardiolipin antibodies. Radiographs of both legs showed marked vascular calcification.

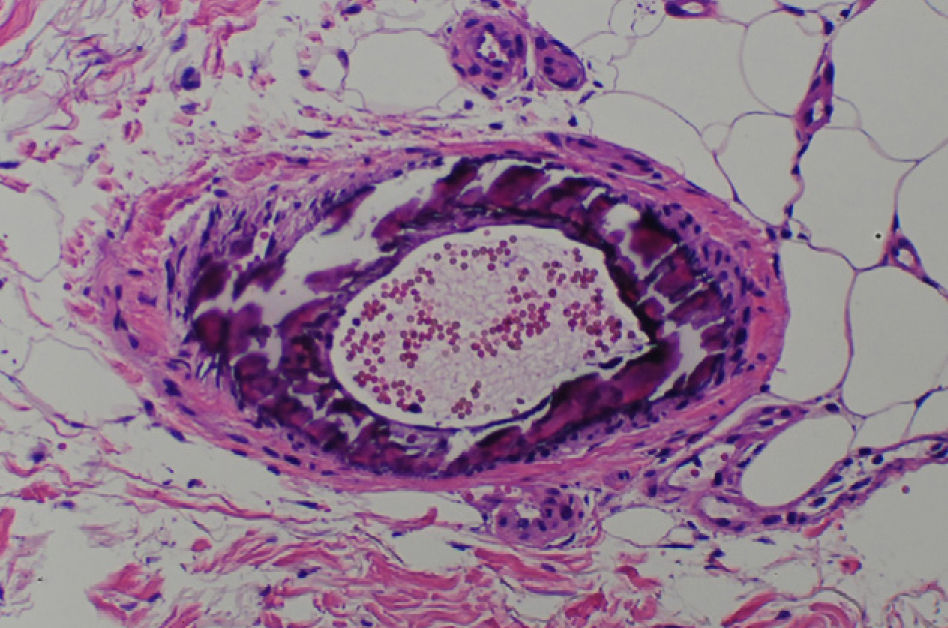

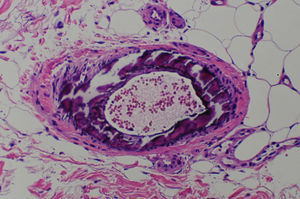

A skin biopsy of the affected area revealed superficial ulceration with necrosis of the superficial dermal collagen, as well as extensive calcification and intimal proliferation in multiple arteries and arterioles (Fig. 2). The calcium deposits in the blood vessel walls were more visible with Von Kossa staining. As there were no extravascular calcium deposits or fat necrosis, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis was confirmed. Because the patient had normal levels of protein C, protein S, parathyroid hormone, calcium, and serum phosphate, a diagnosis of atypical calciphylaxis was established.

In this case the condition was associated with treatment with coumarin derivatives, a phenomenon that has recently been described in the literature. Acenocoumarol was withdrawn and the patient was prescribed enoxaparin anticoagulant therapy at a dose of 1mg/kg every 12h, which led to rapid improvement in both the lesion and local pain. Moreover, the ulcer gradually healed and the livedo rash resolved.

Calciphylaxis is considered atypical when it occurs in patients who do not have renal failure or impaired calcium–phosphate metabolism.6 In such cases, we must consider that the disease may be the result of the interaction between various risk factors, including obesity, liver disease, systemic corticosteroid therapy, elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, white race, female sex, warfarin therapy, vitamin D supplementation, protein C or protein S deficiency, and diabetes mellitus.4

Our patient's kidney and parathyroid function were normal, but other risk factors were present; she was white, she had diabetes mellitus, and she was receiving acenocoumarol, a coumarin-derived oral anticoagulant. Since the anticoagulant treatment was the only risk factor that could be modified, it was withdrawn and replaced with low-molecular-weight heparin, the recommended anticoagulant for patients of these characteristics.8 Atypical calciphylaxis has occasionally been described in association with oral coumarin-derived anticoagulants, which interact with the calcification inhibitor matrix gla protein.9

The differential diagnosis should consider warfarin-induced skin necrosis, which normally appears 3–10 days after start of treatment and is caused by an imbalance between procoagulant and anticoagulant factors. Histopathology of this condition reveals thrombotic occlusion of dermal and subcutaneous venules and veins, surrounded by diffuse fat necrosis and bleeding,10 but no calcification of the blood vessel walls, unlike the case of our patient.

None of the authors in the literature reviewed indicated an association between atypical calciphylaxis and acenocoumarol anticoagulant therapy. Risk factor modification should be considered whenever possible. In our case, the cessation of acenocoumarol was decisive in the favorable evolution of the disease.

Please cite this article as: Álvarez-Pérez A, Gutiérrez-González E, Sánchez-Aguilar D, Toribio J. Calcifilaxia atípica secundaria al tratamiento con acenocumarol. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012;103:79–81.