Cellulitis and erysipelas are local soft tissue infections that occur following the entry of bacteria through a disrupted skin barrier. These infections are relatively common and early diagnosis is essential to treatment success. As dermatologists, we need to be familiar with the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of these infections. In this article, we provide a review of the literature and update on clinical manifestations, predisposing factors, microbiology, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. We also review the current situation in Chile.

La celulitis y la erisipela son infecciones localizadas de partes blandas que se desarrollan como resultado de la entrada de bacterias a través de una barrera cutánea alterada. Es una entidad de presentación relativamente frecuente y su diagnóstico precoz es clave para el tratamiento oportuno del paciente, por lo que debemos estar instruidos en su clínica, diagnóstico y alternativas de tratamiento. En este trabajo, se realiza una revisión de la literatura y actualización en el tema que incluye: manifestaciones clínicas, factores predisponentes, microbiología, diagnóstico, tratamiento y complicaciones. Además, se realiza una revisión de la situación bacteriológica actual en Chile.

Cellulitis and erysipelas are common localized soft tissue infections that occur following the penetration of bacteria through a skin barrier breach. They have an estimated annual incidence of 200 cases per 100 000 population1 and account for up to 10% of all hospital admissions.2 They affect the lower limbs in 70% to 80% of cases and have a similar incidence in men and women. Cellulitis generally occurs in middle-aged and older adults, while erysipela is seen in very young or very old patients.3

Clinical ManifestationsErysipela affects the superficial dermis and the superficial lymph nodes and presents as a well-circumscribed, firm, elevated, erythematous plaque with local heat and pain on palpation. It most often affects the face.

Cellulitis affects the reticular dermis and hypodermis and can cause permanent lymphatic damage. The affected area is characterized by local heat, edema, pain, and erythema. The plaque has irregular borders and may contain areas of normal skin that follow an unpredictable pattern.4 There may also be blisters (Fig. 1), hemorrhagic bullae, and pustules that can progress to ulcers and coalesce to form superficial abscesses.5 Cellulitis most often affects the lower limbs.

Systemic manifestations may be present and are probably due to an inflammatory immune response to streptococcal toxins. A minority of patients develop severe sepsis, local gangrene, or necrotizing fasciitis.

Clinically, cellulitis and erysipelas can be difficult to distinguish and may even coexist. Some clinicians, particularly in Europe, consider the entities to be identical (with erysipela considered to be a superficial form of cellulitis).6 In this review thus the term cellulitis also refers to erysipela.

Predisposing FactorsLocal Factors- -

Interdigital intertrigo. This is the main clinically evident route of entry. The bacterial reservoir is typically located in the interdigital spaces, which are colonized by Streptococcus bacteria or Staphylococcus aureus.7,8 Approximately 77% of patients with cellulitis have a route of entry, which may be a superficial fungal infection in up to 50% of cases.9

Dermatomycosis is a significant risk factor for cellulitis (OR, 2.4; P <.001), together with interdigital tinea pedis (OR, 3.2; P<.001), plantar tinea pedis (OR, 1.7; P=.005), and onychomycosis (OR 2.2, P<.001).10

- -

Previous skin barrier breach due to ulceration, trauma, edema, radiation therapy, or dermatosis.11

- -

Venous insufficiency due to stasis dermatitis, venous ulcers, or lymphedema.

- -

Lymphedema following lymph node dissection (breast cancer surgery)12 or a lymphatic disorder.

- -

Previous cellulitis. Lower limb cellulitis recurs annually over a period of 1 to 3 years in 8% to 20% of cases. The site of recurrence is usually the same as the first site.13

- -

Previous saphenectomy. Cellulitis can occur shortly after a saphenectomy or years later (mean, 8-10 months).6

- -

Location. Recurrent cellulitis is particularly common in the pretibial area.13

- -

Obesity associated with venous insufficiency, altered lymphatic drainage, increased skin fragility, and deficient hygiene.

- -

Others, including tobacco use (a risk factor for recurrence), diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, immunosuppression, and a history of cancer. There have been reports of genetic susceptibility.6,12,14

Cellulitis is caused by direct bacterial invasion through a break in the skin barrier. The extent of soft tissue involvement is variable. Exceptionally, it can be caused by a bacterial infection from another site, particularly in immunosuppressed patients.

Despite the wide heterogeneity in studies that have analyzed the microbiology of cellulitis, approximately 10% of typical cases of lower limb cellulitis are thought to be caused by Staphylococcus aureus and between 75% and 80% by different strains of Streptococcus (mainly group G β-hemolytic Streptococcus but also group A).15,16 These bacteria produce several toxins such as streptokinase and DNase B that can trigger a marked inflammatory reaction. There are few cases of concomitant infection by the above bacteria or by gram-negative bacteria or Enterococcus.

In one study, the most common pathogen identified in blood cultures from patients with erysipela was group G streptococci, followed by group A streptococci.17

Unusual causative agents should be suspected in the following cases:

- -

Diabetics with chronic ulcers. Suspect anaerobic and gram-negative bacteria.18

- -

Crepitus or a grayish, foul-smelling secretion. Suspect anaerobic pathogens (Clostridium perfringens, Bacteroides fragilis, Peptostreptococcus spp., and Prevotella spp.). Surgical debridement and antibiotics are required in such cases.15

- -

Patients after a pelvic lymph node dissection. Suspect Streptococcus agalactiae.19

- -

Patients with a compromised immune system, rheumatologic diseases, chronic liver damage, or nephrotic syndrome. Suspect gram-negative bacteria, Streptococcus pneumoniae,20 or Cryptococcus neoformans (anecdotal cases reported).21

- -

Special exposure cases. Suspect Capnocytophaga canimorsus and Pasteurella multocida (rapidly progressing cellulitis, generally with lymphangitis) in dog or cat bite injuries; Eikenellacorrodens in human bite or clenched fist injuries22; Vibrio vulnificus in tropical climates or in patients who have eaten shellfish or been in the sea23; Aeromonas spp. in patients who have been in fresh water or in contact with leeches; and Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae (erysipeloid) in patients who have handled raw fish or meat.24

- -

Children with periorbital-orbital cellulitis. Suspect group B β-hemolytic Streptococcus in newborns and infants under 3 months of age; Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type B (reduced incidence since introduction of vaccine) in children under 5 years of age; and Staphylococcus aureus and group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus in children over 5 years of age.25

- -

Children with perianal cellulitis. Suspect group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus.26

Diagnosis of cellulitis is based on clinical manifestations. White blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein are generally elevated, but values within normal ranges do not rule out a diagnosis. Blood cultures are positive in less than 5% of cases and are only ordered in patients with systemic toxicity, immunosuppression, or very extensive disease.6,27,28 Purulent infections such as pustules and abscesses must be drained and cultured. Another means of identifying causative agents is by investigating systemic immune response to streptococcal antigens (A, C, and G) via determination of antistreptolysin O (AS), antideoxyribonuclease b, and antihyaluronidase titers. Evidence of a recent streptococcal infection is observed in up to 70% of cases of lower limb cellulitis.29

TreatmentGeneral MeasuresManagement of predisposing factors, elevation of affected area, skin hydration (to repair the skin barrier).

Anti-inflammatory Drugs- -

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Ibuprofen 400mg every 6hours for 5 days combined with antibiotics can accelerate the resolution of cellulitis.30 It should be noted, however, that NSAIDs can mask a deep necrotic infection.

- -

Corticosteroids. Combining prednisolone for 8 days and penicillin also accelerates resolution and may result in an earlier switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics, a shorter hospital stay, and possibly a lower risk of recurrence during the year of follow-up.31

These findings, however, need to be corroborated by more studies.

AntibioticsCellulitis is treated with systemic oral or parenteral antibiotics. Based on the assumption that the main pathogenic agent in cellulitis is Streptococcus, several European guidelines recommend penicillin as the standard line of treatment. This approach, however, is supported by few studies.

With antibiotics, pathogens die more quickly, releasing toxins and enzymes that initially result in what appears to be clinical worsening, with greater skin inflammation and fever. This should not be confused with treatment failure.6 Clinical improvement is generally seen within 24 to 48hours of treatment initiation and can be observed up to 72hours.

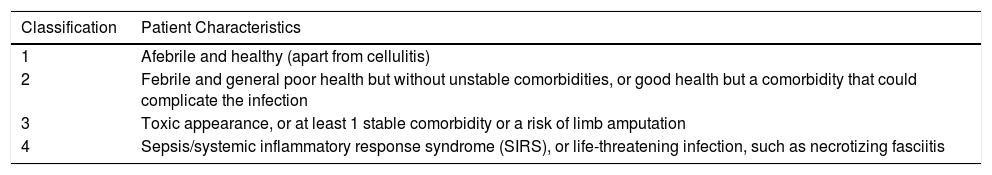

Most patients develop mild cellulitis that can be treated with oral antibiotics. Parenteral antibiotics are recommended for patients with signs of systemic toxicity, a compromised immune system, rapidly progressing or persistent erythema, or progression of symptoms after 48 to 72hours despite administration of standard treatment. Newborns and infants under 5 years of age, who usually develop periorbital or orbital cellulitis, generally require hospitalization and intravenous therapy.32 The classification system described by Eron et al.33 for skin and soft tissue infections is based on severity of local and systemic signs and symptoms of infection and the presence of clinical instability and comorbidities. This classification system helps to guide decisions regarding hospitalization, antibiotic treatment, and administration route (Table 1).33

Classification System for Skin and Soft Tissue Infections Described by Eron et al.33

| Classification | Patient Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1 | Afebrile and healthy (apart from cellulitis) |

| 2 | Febrile and general poor health but without unstable comorbidities, or good health but a comorbidity that could complicate the infection |

| 3 | Toxic appearance, or at least 1 stable comorbidity or a risk of limb amputation |

| 4 | Sepsis/systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), or life-threatening infection, such as necrotizing fasciitis |

Treatment duration should be decided on a case-by-case basis. A period of 5 days is generally recommended for patients with uncomplicated cellulitis, but treatment may need to be extended to up to 2 weeks for serious or slow-responding infections.26

Erythromycin and clindamycin are generally recommended for patients allergic to penicillin.

The first line of treatment recommended in the Manual of Antibiotic Therapy and Control of Infections for Hospital Use issued by the Faculty of Medicine of the Pontificia Universidad Católica in Santiago, Chile is intravenous cefazolin 1g every 8hours following by oral cefadroxil 500mg every 12hours for 10 to 15 days for cellulitis and 7 to 10 days for erysipelas.34

The current recommendation is to base choice of antibiotic treatment on whether the cellulitis presents with purulence or not.5,29

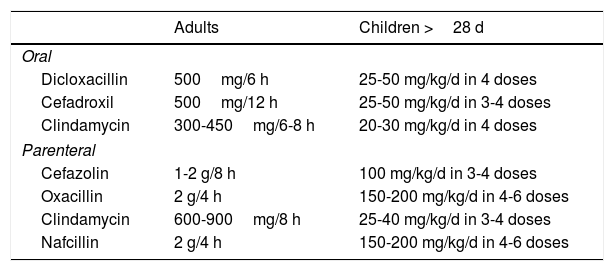

Nonpurulent CellulitisNonpurulent cellulitis does not present with purulence or abscesses. It should be treated empirically to provide coverage against β-hemolytic Streptococcus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Table 2).

Empirical Treatment for Nonpurulent Cellulitis (Not Including MRSA).

| Adults | Children >28 d | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral | ||

| Dicloxacillin | 500mg/6 h | 25-50 mg/kg/d in 4 doses |

| Cefadroxil | 500mg/12 h | 25-50 mg/kg/d in 3-4 doses |

| Clindamycin | 300-450mg/6-8 h | 20-30 mg/kg/d in 4 doses |

| Parenteral | ||

| Cefazolin | 1-2 g/8 h | 100 mg/kg/d in 3-4 doses |

| Oxacillin | 2 g/4 h | 150-200 mg/kg/d in 4-6 doses |

| Clindamycin | 600-900mg/8 h | 25-40 mg/kg/d in 3-4 doses |

| Nafcillin | 2 g/4 h | 150-200 mg/kg/d in 4-6 doses |

Monotherapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is indicated for uncomplicated infections, i.e., infections without systemic manifestations or comorbidities; this treatment has a comparable effectiveness to clindamycin.35

Neonates generally need to be hospitalized and administered empirical parenteral treatment with vancomycin and cefotaxime or gentamicin (coverage for group B and others groups of β-hemolytic Streptococcus and MRSA).29

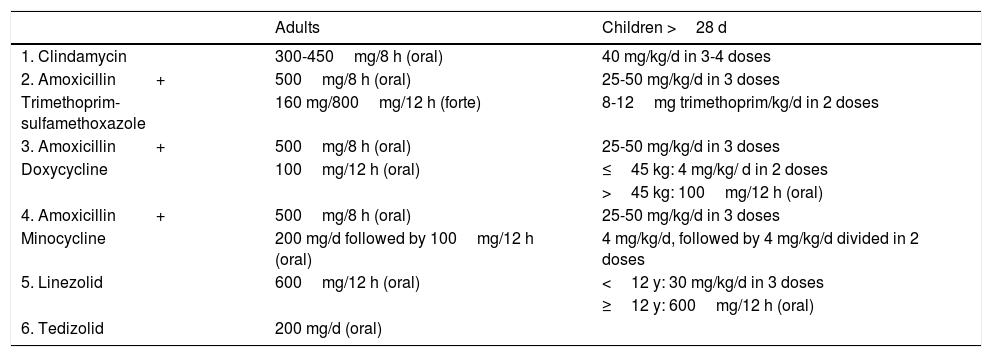

The treatment options when both β-hemolytic Streptococcus and MRSA are suspected are provided in Table 3.

Empirical Treatment for Cellulitis Due to β-Hemolytic Streptococcus+Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

| Adults | Children >28 d | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Clindamycin | 300-450mg/8 h (oral) | 40 mg/kg/d in 3-4 doses |

| 2. Amoxicillin+ | 500mg/8 h (oral) | 25-50 mg/kg/d in 3 doses |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 160 mg/800mg/12 h (forte) | 8-12mg trimethoprim/kg/d in 2 doses |

| 3. Amoxicillin+ | 500mg/8 h (oral) | 25-50 mg/kg/d in 3 doses |

| Doxycycline | 100mg/12 h (oral) | ≤45 kg: 4 mg/kg/ d in 2 doses |

| >45 kg: 100mg/12 h (oral) | ||

| 4. Amoxicillin+ | 500mg/8 h (oral) | 25-50 mg/kg/d in 3 doses |

| Minocycline | 200 mg/d followed by 100mg/12 h (oral) | 4 mg/kg/d, followed by 4 mg/kg/d divided in 2 doses |

| 5. Linezolid | 600mg/12 h (oral) | <12 y: 30 mg/kg/d in 3 doses |

| ≥12 y: 600mg/12 h (oral) | ||

| 6. Tedizolid | 200 mg/d (oral) |

Purulent cellulitis presents with a purulent exudate without a drainable abscess. The presence of pus points to an infection by Staphylococcus aureus.

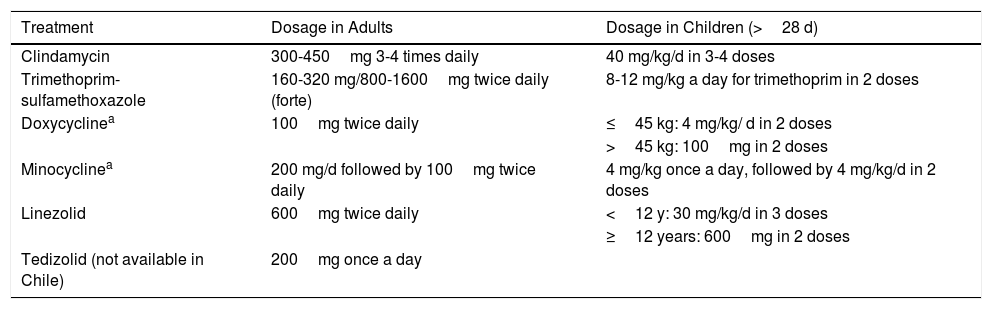

Purulent infections must be treated empirically to provide coverage for MRSA while awaiting the culture results, as up to 59% of purulent cellulitis cases are caused by MRSA.36 Quinolones are not recommended as resistance to these antibiotics is high (Tables 4 and 5).

Oral Treatment for Cellulitis Due to Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

| Treatment | Dosage in Adults | Dosage in Children (>28 d) |

|---|---|---|

| Clindamycin | 300-450mg 3-4 times daily | 40 mg/kg/d in 3-4 doses |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 160-320 mg/800-1600mg twice daily (forte) | 8-12 mg/kg a day for trimethoprim in 2 doses |

| Doxycyclinea | 100mg twice daily | ≤45 kg: 4 mg/kg/ d in 2 doses |

| >45 kg: 100mg in 2 doses | ||

| Minocyclinea | 200 mg/d followed by 100mg twice daily | 4 mg/kg once a day, followed by 4 mg/kg/d in 2 doses |

| Linezolid | 600mg twice daily | <12 y: 30 mg/kg/d in 3 doses |

| ≥12 years: 600mg in 2 doses | ||

| Tedizolid (not available in Chile) | 200mg once a day |

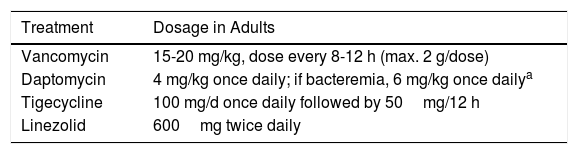

Parenteral Treatment for Cellulitis Due to Community-Acquired Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

| Treatment | Dosage in Adults |

|---|---|

| Vancomycin | 15-20 mg/kg, dose every 8-12 h (max. 2 g/dose) |

| Daptomycin | 4 mg/kg once daily; if bacteremia, 6 mg/kg once dailya |

| Tigecycline | 100 mg/d once daily followed by 50mg/12 h |

| Linezolid | 600mg twice daily |

Community-acquired (CA) MRSA is defined as any MRSA infection diagnosed in an outpatient or an inpatient within 48hours of hospitalization in the absence of the following risk factors: hemodialysis, surgery, hospitalization in the previous year, presence of a permanent catheter or a percutaneous device at the time of previous culture or isolation of MRSA.37

CA MRSA strains are characterized by greater virulence and capacity for rapid duplication and spread. They frequently produce exfoliative toxins and enterotoxins and are not multiresistant (they are only resistant to β-lactams). In addition, over 90% of CA MRSA infections result in the production Panton–Valentine leukocidin, a cytotoxin that causes leukocyte destruction and tissue necrosis, favoring the formation of abscesses.

CA MRSA should be clinically suspected in patients with refractory or aggressive disease, systemic disease, recurrent cellulitis, a history of MRSA infection, or risk factors for MRSA, as well as in patients who have travelled to endemic areas.

Manifestations include highly diverse skin and soft tissue infections, ranging from cellulitis to rapidly progressing necrotizing pneumonia or severe spesis.38

The risk factors for MRSA colonization are recent hospitalization, institutionalization, recent antibiotic treatment, HIV infection, sex between men, use of injectable drugs, hemodialysis, imprisonment, military service, needle sharing, use of razors and other sharp objects, sharing of sports equipment, diabetes, long hospital stays, and pig breeding.39 Additional coverage for CA MRSA should be considered in patients with MRSA risk factors and in people from communities with a prevalence of MRSA infection of over 30%.29,40,41

An increase in the incidence of CA MRSA has been observed in Chile.38,42,43

Over the past 2 years, the Universidad Católica has been working on a research protocol for determining the presence of MRSA in students of medicine. The preliminary results will be published soon.

New antibiotics, such as telavancin, tedizolid, dalbavancin, and oritavancin, could be an option for treating skin and soft tissue infections, including MRSA cellulitis.29,44,45 Telavancin was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2009. It has been shown to be noninferior to vancomycin, but with a higher risk of nephrotoxicity.45

Tedizolid and dalbavancin received FDA approval in 2014. Tedizolid is an oxazolidinone antibiotic with activity against gram-positive bacteria, including MRSA. A daily dose of oral tedizolid is noninferior to linezolid every 12hours.44

Dalbavancin is a second-generation lipoglycopeptide that is administered once a week and provides coverage for MRSA.45

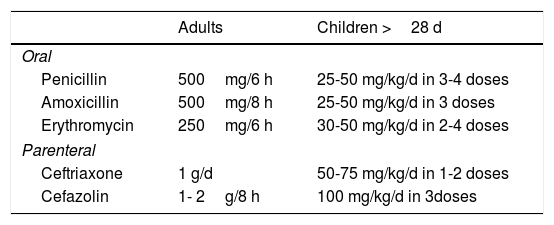

ErysipelaCoverage for just β-hemolytic Streptococcus29 is recommended for patients with evident manifestations of classic erysipela29 (Table 6).

ComplicationsAlthough most cases of cellulitis are successfully treated with antibiotics, long-term complications can occur.

The most common complications are

- -

Persistent edema, which affects 1 in every 10 hospitalized patients.46

- -

Venous ulcers.

- -

Recurrence. Recurrent cellulitis is seen in between 25% and 46% of hospitalized patients over a period of 3 years.46,47 Approximately 11% of outpatients develop a recurrent infection in the first year of follow-up.3

Necrotizing fasciitis is a fast-progressing, destructive skin and soft tissue infection with a mortality rate of up to 50%.48 It can stimulate cellulitis with extensive erythema, although the skin is not necessarily involved initially. It presents with pain that is disproportionate to the clinical findings, in addition to edema, skin necrosis, blisters, skin numbness, fever, and crepitus. It is important to recognize necrotizing fasciitis, as it requires rapid treatment with antibiotics and surgical debridement.48,49

Recurrent CellulitisSuppressive antibiotic treatment is indicated for patients with recurrent cellulitis and predisposing factors that cannot be corrected.29,50

The prophylactic options described in the literature are intramuscular benzathine penicillin (1 200 000 IU a month or 600 000 IU in patients weighing ≤27kg), oral penicillin (250-500mg twice daily), and prophylaxis for staphylococcal infection with clindamycin (150mg/d, usually unnecessary in children).

Patients with a body mass index of 33 or higher and who have had multiple recurrences of cellulitis or lymphedema respond worse to prophylactic treatment.51

Some clinicians recommend basing treatment decisions on the results of serologic tests for β-hemolytic Streptococcus (ASO, anti-ADNsa B, or antihyaluronidase). The last 2 tests are more reliable for diagnosing skin postinfections by group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus).52

The protocol for the Cochrane Review on Interventions for the Prevention of Recurrent Erysipelas and Cellulitis53 has been available since 2012, but no results have been published to date.

ConclusionsIt is important to recognize the manifestations of cellulitis and be familiar with the associated predisposing factors. We recommend searching for and, where appropriate, treating possible routes of entry, such as interdigital tinea and tinea pedis.

Familiarity with management algorithms is also important, as these favor the prompt administration of effective treatment. An integrated management approach is necessary to ensure treatment success.

Finally, it is important to identify and treat early complications and recurrences, and to select candidates for suppressive antibiotic therapy.

Conflicts of InterestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ortiz-Lazo E, Arriagada-Egnen C, Poehls C, Concha-Rogazy M. Actualización en el abordaje y manejo de celulitis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2019;110:124–130.